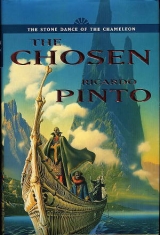

Текст книги "The Chosen"

Автор книги: Ricardo Pinto

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

Osidian brought him other reels. More campaigns. They studied the dates. The days they spoke of were more than a thousand years dead.

'So much carnage,' Carnelian said at last. The beads were becoming shapeless, their voices muffled.

'Even barbarians cannot be brought under a yoke by persuasion,' said Osidian. 'Anciently, they were proud. We broke their will with terror. Once, through fear of the Twin Gods, all the world paid us tribute.'

'Of children?' Carnelian asked, bringing his knees up to his chest, hugging them, seeing Ebeny.

'Not just children, all the fruits of the Three Lands.'

'Is this necessary?'

'If beasts are allowed to come into a garden will they not trample it?'

Carnelian forced himself to consider this.

'Do you wish to read more?'

'No. My fingers can no longer hear the beads.'

'Perhaps it is best. My blood afflicts me.'

'It burns?' asked Carnelian.

'In my bones.'

Carnelian worried that he had never felt it. 'Rewind the cord.'

Carnelian slipped his feet down to the treadle. There was a rattle and a quivering in the chair and then silence. He waited. He could hear nothing. His eyes were making shapes in the dark.

'Come, I will take you back to the door.'

The voice speaking suddenly beside Carnelian made him start. He grew angry. 'How do you see in the dark?'

'See?'

'You find your way-'

The darkness chuckled. There was a fumbling. Sudden light daggered Carnelian's eyes and made him wince. 'You could have warned me.'

'Sssh!'

Carnelian saw Osidian's eyes were the purest jade.

Take off your shoes, he signed.

What? Carnelian chopped back.

'If my Lord pleases, his shoes…'

Grumbling, Carnelian stooped and took them off.

Osidian urged him off the chair. The light receded as he walked away, backwards, still hooking his finger at Carnelian to follow.

Carnelian did so, grinding his teeth, wanting to hit him.

And?

Carnelian opened his hands, not understanding.

Your feet. Do you feel nothing under your feet?

Carnelian became aware the floor was textured. He looked down, crouched. Bring the light closer, he signed. As the floor brightened, he saw it was carved. He touched the embossed surfaces. Osidian's white hand strayed across some patterns.

'All of these are paths,' he whispered. 'You follow them with your feet. North Door, South Door.' He stroked one pattern after another. 'East Door, West.' Still crouching, he rocked himself a little way off and pointed down. Carnelian followed his finger, touched the eye carved into the floor.

The path to the moon-eyed door.'

'Exactly.' Osidian stood up. 'Will my Lord care to try for himself, this seeing in the dark?'

Carnelian straightened, smiling even as the light went out. He found the eye with his toe. He took a step and after sliding his foot around a bit found another eye. He took another step.

'Like stepping stones,' he muttered, finding the measure of the stride that took him smoothly from one eye to the next.

He followed the path, at first certain that he was about to walk into a bench or a wall. After a while he grew more confident and soon was moving comfortably through the darkness.

He seemed to have been walking for ever when suddenly he stepped forward and there was no eye under his foot. He stopped and Osidian walked into him. Carnelian clutched him to avoid falling. The body under his fingers was like wood. He could smell Osidian's skin. 'My Lord, forgive me.' He stepped back.

'Hide your eyes,' Osidian said.

Light flared. Carnelian squinted till his eyes were able to see again. Looking round, he saw they were standing near the silver door. He began putting on his shoes.

'Will you come again?' Osidian asked.

Carnelian looked up at him, nodded.

As he walked back, Carnelian caught a scent coming off his shoulder that he recognized was Osidian's.

Carnelian smiled when he saw Osidian waiting for him.

'Will we be able to go together in darkness?' he asked.

Osidian shook his head. He pointed at the floor. 'Which path would you follow?'

Carnelian looked. The stone was as marked with trails as mud at a market.

There are paths here leading to various points in the library but none going to the chamber I want to go to.'

Carnelian deflated. Then one must know where the chamber lies in the library maze?'

Osidian lifted his hand in the affirmative. 'A labyrinth can be a better defence than the strongest gate. Still, we can go through the darkness like children.' He offered Carnelian his hand.

Carnelian looked at it, embarrassed, shook his head. 'It would be easier to use the lantern.'

Osidian took back his hand and frowned. 'As you will.' He strode off stiff-shouldered.

Cursing himself, Carnelian followed.

All that day Carnelian read the annals of God Emperors whose column sepulchres, Osidian told him, were some of the first put up in the Labyrinth. Carnelian came to realize that once the Labyrinth had been only a processional way. He was reading faster and hardly had to ask Osidian to help him.

Later, when he had grown weary of the interminable descriptions of conquest, he told the darkness that he wanted to leave. He found Osidian's hands as they fumbled with the lantern and gripped them. There is no need for light, no need for you to come. I will make my way back to the door myself.'

'And tomorrow?' said the darkness.

Carnelian felt as if he were in a dream haunted by the voice in the beads.

'We could try something different tomorrow, if you want.'

'Like what?'

'Well, there are chambers filled with the reels of the Law and its commentaries, with the "Ilkaya" and other mystical works. There are technical treatises on just about any topic you could imagine. The records of the flesh tithe, tribute, taxation of the cities, censuses of the barbarian tribes. The Books of Blood-'

'Where the blood-taints of the Chosen are kept?'

'Every Chosen who has ever lived.'

The Books of Blood then,' whispered Carnelian, and, taking the unlit lantern, he strode off along the path of eyes.

The following day, Osidian was waiting for him. The walk through the library seemed longer than usual. They reached a chamber that smelled of freshly spilled blood. Uneasy, Carnelian lifted his lantern. It was a chamber larger than the others with many benches. All the bead-cord he could see was dull and black. The reels were only as thick as his wrist. He took the lantern close to one, ran his fingers over its beads, then smelled them. It was as he had suspected. 'Iron.'

These are the Books of Blood,' said Osidian.

Carnelian looked round, trying to calculate the value of such treasure.

'Look here,' said Osidian, touching the tip of a spindle.

Carnelian came to look. Carved into its top was the cypher of a Chosen House.

'Your reels will be over there somewhere, with the rest of the Great,' Osidian whispered near his ear.

Carnelian walked away in the direction indicated. Spindle by spindle they searched for the chameleon, moving from one bench to the next.

'Here,' hissed Osidian.

Carnelian joined him and saw the chameleon carved dancing into the spindle's tip above the six stacked reels. How many people of my House? he signed.

Osidian shrugged. 'Your House is as ancient as the Commonwealth.' The beads clinked like armour as he ran his fingers down the stack. The reels are fat. The blood-taint of maybe,' he shrugged again, 'eight twenties of generations.'

Carnelian took hold of the topmost reel. He could feel the beads shifting under his hands. He lifted the reel carefully off the chameleoned spindle. It was as heavy as a stone. Osidian pointed out a chair. Carnelian carried the reel against his chest and impaled it on the chair spike. He was glad when Osidian closed the lantern's shutter. For some reason, the reel's rusty blacks were reminding him of massacres.

The beads soon absorbed him. They were simple to learn. Most of the beadcord was made up of the numbers one to nineteen, with a bead like a berry for zero. It was strange to feel the first name he came to was his own. He ran the cold, rough beads through his fingers again and heard them say his name, Carnelian. The beads after that were his blood-taint: zero, zero, one, nineteen, zero, nine, fourteen, sixteen, nine, thirteen, fifteen. The next name along the beadcord was his mother's, Azurea, followed by the first few beads of her blood-taint: zero, zero, zero. He ran the beads through his fingers again. Three zeros. Blood-rank three. Such purity. It made him proud. He read the next numbers almost trying to feel something of his mother in them. Two, one, three, nineteen, nine, sixteen, seventeen, ten. There was nothing there but cold iron. Beyond the separator bead was Suth Sardian, his father, and the numbers: two zeros matching his and then a three, fifteen, nineteen, fifteen again, ten, three, two, ten.

He read on, finding Spinel's blood-taint and the others of his House's second lineage. Next came the third lineage. Then he found his grandfather's name, his grandmother Urquentha's, the parents of Spinel and so on, further and further back in time. His father's father's father. Numbers and strange names rolled through his head as he wound them up from the ancient past.

He released the beadcord, sat back bewildered, awed by the tale of years, feeling he was like the Pillar of Heaven holding up a skyful of ancestors.

'I've had enough,' he whispered. He had forgotten Osidian. Convinced suddenly that he was alone, Carnelian felt around. His hand found him.

'I am here, Carnelian. Where else do you think I would be?'

'Looking up your own bloodline.' There was a long silence. 'I know my blood,' Osidian said. 'I did not mean-'

'It does not matter,' whispered Osidian. 'Can you find your own way back?' 'Well, yes

'Farewell then,' said Osidian and with a waft of air was gone.

Later, in his chamber in the Sunhold, Carnelian was wondering for the hundredth time if he would ever see Osidian again. He had replayed those last few words endlessly in his mind. Each time he had felt a stabbing in his guts. Why had he so carelessly offended him? His stomach ached as the words circled round in his head like carrion crows.

He went to bed early and ate nothing. Sleep would not come. When it did, it brought dreams. All night he fumbled blindly over a stony beach seeking the pebble that would whisper to him its answer.

Carnelian awoke feeling tired. Sullenly, he determined he would not go to the moon-eyed door. He told himself that he did not want to. Eventually he had to confess he was reluctant to go in case Osidian should not be there. He turned his anger on himself until fear of never seeing Osidian again made him leap up. He rushed through his dressing, cursing. It was already morning.

He took less care going to the trapdoor than usual. Halfway down the steps he found that he was counting them, swore and stopped, though each footfall was like a bead slipping through his fingers. He thought he had prepared himself for the disappointment but when he reached the moon-eyed door he found its blank gaze withering. Osidian was not in his usual place. That was the end of it. Still, he could not bring himself to turn away. He heard the clink and saw it opening. Osidian walked out and Carnelian lurched a few steps towards him then stopped. 'Osidian.' Relief thinned his voice.

The boy's eyes were like summer sea. He twitched a smile. 'What shall it be today, my Lord?'

Carnelian tried to think through the blood pulsing in his head. He ran through what he remembered Osidian had said the day before. 'History?' he suggested.

Osidian showed surprise. 'I thought you did not like history.'

There is more to history than conquests.' He racked his mind for a topic. For some reason he recalled the Masters arguing theology that night on the watch-tower roof.

The beginning.'

The creation?'

The beginning of the Commonwealth. The Quyans. The Great Death. Does the library contain reels going that far back?'

Osidian's brow creased. 'I have never sought such antiquity. What you speak of is more religion than history. Still…'

Carnelian grew calm watching Osidian thinking. There was so much he wanted to know about this strange boy but he feared to make even the smallest enquiry.

There is one place to find out if such a reel exists.'

'Let us go there, then.'

Osidian made his hand into a barrier sign. 'Less haste. We will have to be careful of the Wise. Most of them are busy calculating the Rains' arrival, arranging the Rebirth; that is why we have seen nothing of them. But what you seek lies at the library's heart, the very centre of their web. Many will still be there and they will detect the slightest vibration. We must be as silent as shadows.'

Carnelian nodded, his pulse quickening again.

Carnelian crept into the library after Osidian, who was holding the lantern up to light their way. After a few chambers, Carnelian reached out to touch Osidian's shoulder. The boy turned round, raising his eyebrows.

The lantern? Carnelian signed.

Osidian grinned. Yes, it is one.

Carnelian made a face at him. It is very bright.

Here the only eyes are ours, replied Osidian, constructing complicated signs with his free hand. The light will help you amid bumping into anything.

Carnelian gave a snort and they went on.

He soon lost count of the chambers. They were moving between the benches of another when he almost ran into Osidian who had come to a sudden halt. Carnelian followed the direction of his gaze and saw a Sapient with his pleated waxy noseless face, the black almonds of his eyes alive with malice. He came round the bench towards them. When he was between two benches, he stretched the four fingers of each hand out to either side. The fingertips settled on the benches like feathers failing from the air. The hands tensioned like exquisite traps. The Sapient stood motionless, a spider waiting.

From the corner of his eye, Carnelian caught a tiny white movement. He turned his head slowly, keeping an eye on the Sapient. Osidian, his eyes round, signed with his free hand, Not a blink. His fingers feel everything.

The Sapient's hands jumped up from the benches. Carnelian focused fully on the creature as he came treading towards them, his long white feet sucking to the floor like mouths, his fingers swimming, sensing currents in the air.

Carnelian looked desperately for an escape. The coldness of the floor was making his feet ache but he dared not move. Sweat was trickling down the gutter of his spine. Some was oozing down his nose. He feared that it might collect in a drop and fall, betraying them. He drew his shoulders back, his head further still, drawing away from the four-fingered hands. The Sapient stopped between two new benches. Again, he deployed his hands then froze. Carnelian looked from the cages of fingers to the black insect eyes. He could smell the Sapient's musty odour.

The hands lifted and Carnelian turned his head away. He suppressed a shudder, anticipating the touch of those moist fingers. He might have fled, save that just then the Sapient turned and swiftly returned to where he had been. Carnelian watched him reach down to a bench's bronze ring and pull at the tail of beadcord hanging from it. The beads slipped through his fingers. Then both his hands rose to lift the topmost reel off the spindle above. This was swiftly transferred to the empty spindle beside it. The hands returned to pluck up the second reel. Cradling this in his arms, the Sapient slid through a door and disappeared.

Carnelian gulped in a breath, another. He found that Osidian was grinning at him. Crookedly, Carnelian grinned back.

Do you want to go on? signed Osidian.

Carnelian's nod was rewarded with a look of approval.

They encountered more Sapients. Mostly they were folded into the niches on spinning-wheel chairs, caressing words from beadcord. Sometimes Osidian would lift the lantern high and pull its hem of light up the dark, brocaded robe to find the leather of a Sapient's face and put a fierce glint in the jet eyes. Each time Carnelian recoiled, distrusting the blindness, certain that the Sapient must feel the light tickling over his flesh. But the Sapient would continue reading undisturbed, looking as if he were busy spinning jewelled thread.

They came at last into a chamber in which their light flashed among tall screens that seemed hung with coloured water. Osidian entered boldly. Carnelian was reluctant to follow but did not want to appear afraid. He looked back. The way they had come was utterly black. He shuddered, imagining returning blind through the darkness infested with the Wise.

He caught up with Osidian whose hand was playing through the jewelled shrouds.

He must have heard Carnelian for he turned. Hold this, he signed and pushed the lantern onto Carnelian, then continued reading.

Carnelian saw the screens were like huge folding books whose pages were like harps strung with beadcord. As he watched Osidian's fingers stroking across the strings, Carnelian almost expected to hear music. Osidian shook his head and padded away. Carnelian followed him, holding the light of the lantern over them as if he were carrying a parasol. He tapped Osidian on the shoulder.

What is this place? he signed, having to resort to difficult one-handed signs.

The Master Index, signed Osidian.

Carnelian followed him deeper into the bead partition maze of indices. Sometimes through one crystalled wall Carnelian would see a Sapient moving past or racing his hands over the surface of an index.

Suddenly, Osidian shot him a grin and made a triumph gesture. After he had read down a beadcord he signed, Come, I know where to go now.

Carnelian touched the cord he thought Osidian had been reading. There were words, numbers, but he could make no sense of them.

He was glad to leave the Chamber of the Master Index, following Osidian back into the smaller rooms of the library proper. They had to creep through a fearful region filled with the Wise. Gradually the chambers became free of them and Carnelian relaxed enough to risk more solid footfalls. Exhaustion sapped him as he released the tension in his muscles.

Osidian stopped at a door. This should be the place.' He was fingering something to one side of the door. Carnelian played some light on it. Beadcord hung on the wall like a tapestry. Osidian muttered something and nodded. The reels are here as the index said.' The chamber seemed much the same as any other. Tut the lantern on a bench and help me look.'

'What are we looking for?'

'I am not sure. The index did not give the names of the works, only that they were written Pre-Commonwealth.'

Carnelian moved to the nearest bench. His fingers found a bronze ring with its title beadcord. He began to feel his way down the beads. They were smooth and of no distinctive shape. He moved to the next cord. It was the same. And the next. As he held the first bead, he concentrated all his mind on his fingertips. He took the weight of the cord with his other hand so that he could lighten his touch on the bead. It was not smooth. There was the faintest ridge, but he could not hear what it said. It was like the most delicate whisper. He let the cord go. He looked up and saw Osidian's shadow body away off across the chamber. He picked up the lantern and went to join him. Osidian had a beadcord title clenched in his fist.

'What are you doing?' Carnelian whispered. 'Heating the beads.' Carnelian blinked.

'Sometimes, heating them makes them speak. Paagh.' 'Nothing?'

'Not enough.' Osidian reached up to the nearest reel. He found its end, rubbed a few beads between his fingers. He shook his head.

'Perhaps time has worn them smooth,' said Carnelian.

'No.' He took in the chamber with a sweep of his hand. 'It is just that the Wise have made sure that the beadcord here shall only be read by their fingers.'

'I see,' said Carnelian, disappointed, looking at the reels.

Osidian grinned at him. 'I know a thing or two. We shall return.' He saw the question on Carnelian's face. 'You will find out what I am talking about, but only tomorrow.'

'What is it?' whispered Carnelian.

Earlier, when he had found Osidian waiting for him by the moon-eyed door, the boy had given him an enigmatic smile and then led him to the chamber they had been in the day before.

Carnelian looked at the phial Osidian was holding up. It was a helix of quartz with a hinged silver cap. Within its murky worm-like body he could see a yellow liquid.

Osidian smirked. 'It is something the Wise drink. It has… let us say, some useful effects.'

Carnelian looked at Osidian's green eyes. He did not like the idea of acquiring any habit from the Wise. He wondered at Osidian's mood. Carnelian almost asked him to drink first, but he did not want Osidian to think that he thought it poison.

'How much?'

'A sip will do.'

Carnelian flipped open the cap and sniffed it cautiously. Its iodous smell nipped his nose. He looked at Osidian who gave him an encouraging nod.

'Do you think I would try to poison you?'

Carnelian answered him by putting the phial to his lips and letting some of its liquid trickle onto his tongue. Its bitterness forced a grimace. He swallowed quickly, sucked his tongue, then licked his teeth to try to rid his mouth of the taste.

Osidian took the phial from his hand and drank. Carnelian was pleased to see his face scrunch up. 'It really is foul,' said Osidian, glaring at the phial.

'And now?' whispered Carnelian.

'Now, we wait.' Osidian shuttered the lantern. In the darkness, Carnelian felt the bench shudder as Osidian, sitting down, threw his back against it. Carnelian slid down beside him. He tried to make conversation, to ask what they were waiting for, but Osidian answered every question with an irritating, 'Wait and see.'

The tingling grew as if coming from far away. Carnelian adjusted his position. Against his back the bench seemed to have become the trunk of some vast tree. His back ran up it for a great length. Carnelian found himself wondering if the yellow potion had made him grow like a giant. His legs had stretched so much they must have pushed his feet into the next chamber. He lifted his hand and it swung up like a crane. He fingered the air, half believing that he would find the ceiling of the chamber just above his head.

'Do you feel it?' asked Osidian's breath. Carnelian could feel its wet heat catching in the folds of his ear. He turned his head and was momentarily disorientated by the thick currents of air that he ruddered into motion. His lungs seemed as large as the sky. He breathed in all the winds.

'My lungs are the turtle's shell,' he said.

Osidian's chuckle was like a shunting of machinery. 'You feel it all right.'

Carnelian felt the earthquake of Osidian rising.

'Stand up,' came Osidian's words, tumbling down from above. Carnelian felt fingers fumble into his like an avalanche of pillars. They kept sliding round and through his until they locked closed. Even lying naked on a rock, Carnelian had never felt such a vast expanse of his skin touching the world. Their hands were a jumble of warm stones in whose crevices lay thrilling moisture.

Suddenly the whole meshed mass of fingers were flying skywards. Carnelian's forearm followed, then his elbow, then his upper arm, all straightening like the links in some monumental chain. The whole mass of him unfolded up and up, faraway joints opening until he found himself standing.

'We should release each other's hand,' rumbled Osidian.

Carnelian struggled. Their flesh seemed wedded together at the hands. When they managed to wrestle their fingers apart, Carnelian was left feeling as if part of him had been cut away. It was all he could do to not flail the night to recover it.

Take some beadcord in your hands.'

Carnelian had to wait for the loss to fade before he ran a finger along the wooden wall of the bench. It had been smooth before. Now it was pitted, gnarled, scored with ruts. His finger ran into something that at first he though must be a skull. He felt the heat radiating from Osidian's fingers touching the other side of the curving ball of bone.

'Can you read it now?' asked Osidian.

Carnelian was startled when he realized he was only touching a bead. He allowed his fingers to explore its landscape. They found the ridges, the sensuous curves. Cool regions, warm strips his mind told him must be narrower than a hair. 'I do not recognize it,' he said.

'Let me.'

Osidian's fingers resumed contact. Carnelian felt as if his skin was drinking from Osidian's. He let his hand climb down from one bead to another until it was a safe distance away.

'Untouchables,' said Osidian.

Carnelian could feel the vibration in the cord. Something was coming down it. His hand escaped further down, bead by bead.

'Removing the Blood… no, the Liver,' said Osidian.

A whole earthful of flesh brushed past Carnelian and set his entire skin quivering like a bell's.

Osidian had moved to the next title cord. 'Preserving the Viscera in Canopic Jars.'

Through the floor, Carnelian could feel the quake as Osidian moved further along the bench.

'Hooking out the Cranial Organs.'

'What?' said Carnelian.

'Peh!' said Osidian. These are nothing but manuals of embalming.'

'Is it a secret art?' asked Carnelian, with a sour taste in his mouth.

'One of the most secret.'

'Not something I desire to learn,' said Carnelian, not bothering to hide his disappointment. 'Nor I.'

Carnelian felt suddenly very angry. 'Is that it then?' he asked loudly. A fleshy door closed over his mouth.

'Hush!' whispered Osidian and took his hand away.

'If these are the most secret books in the Library of the Wise,' whispered Carnelian, 'then, my Lord, I am grown weary of their tame marvels.'

A heavy silence fell. He listened for and found the breeze of Osidian's breathing. 'Does my Lord challenge me to find for him a diversion that is less tame?' the darkness said through a smile.

'Well, if-'

Tomorrow, come to the usual place but wear warm clothes and heavy outdoor paint. Tell your people not to expect your return for three days.'