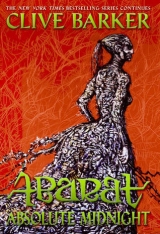

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“There’s a time coming, Mama says, when someone with my genius for wicked things will be really useful. I mean, I’m going to be a King, at least. Probably something more than a King. What’s more than a King? Oh, like someone who kills a King. That’s what I’m going to be. Because if you kill something you’re more important than whatever you killed. Mama didn’t tell me that. I just thought it up myself. Because I have these dreams, see, where it’s the future, and everything boring and good is being lined up to be killed. They’ll have their heads chopped off. I might do the chopping, but no, that’d be boring wouldn’t it? I hate being bored. That’s why I’m going to leave very soon. . . .”

And so he went on, an endless speech about Jollo, Jollo and more Jollo. When they eventually emerged from the trees they saw before them a shallow bay with a short, wooden jetty that jutted from the steep beach. Candy and Malingo exchanged looks of relief. They were going to be out of the boy’s company very soon.

Jollo, however, had one subject left to pontificate upon.

“When I leave here,” he told Candy, “I’m going to be taking all of Mama’s magic books with me, because she’s got books that there’s only one of, and I could get thousands of paterzem for a magic book that there was only one of, right? So do you want me to bring them to you first? I know the geshrat’s too stupid to read a big book, but you’re famous aren’t you? Mama told me before you arrived—” They were on the jetty now, the boards creaking beneath them.

“She knew I was coming?” Candy said.

“Excuse me,” Jollo snarled. “I was still talking. How dare you interrupt me? You know what? I’m not going to bring Mama’s books. Not when you’re so rude. I can’t believe that! Ignorant peasant! Don’t try groveling because that won’t get you anywhere. Grovelers are pathetic. Like my brother. He used to grovel when I kicked him really hard. I’m going to miss him. I won’t have anyone to kick. I just had a brilliant idea! I’ll forgive you for being rude, and I’ll bring you the books like I said I would. All you have to do is leave the geshrat here. I won’t hurt him badly. I’ll just do the same stuff I did with my brother. You know, kicking and spitting and stuff. That’s a good deal, right? I mean, when I’m King you’re going to be so glad I forgave you because otherwise your life won’t be worth living.” He grinned. “Like my brother. I got his life because I’d made his so miserable.” The grin broke into squalid laughter. “That’s the stupidest thing anybody ever did, isn’t it? When I’m King I’m going to make him a saint. He’s going to be Saint Covenantis, the Patron Saint of Stupid People! Ha! I love that! He’ll have his own Holy Day. Today, the day he died. Nobody will work. They’ll just say stupid prayers for a stupid saint of stupid people. Wait! What’s your geshrat doing.”

Candy didn’t answer.

“Tell me! Oh. Oh, I get it. You need permission to speak, right? You may now speak. Tell me what your geshrat’s doing.”

“Are your eyes bad?” Candy said.

“No. My eyes are perfect.”

“Then you can see what he’s doing. Standing in the small boat, untying the rope.”

“Well, tell him to get out of the boat. We made a deal, you and me. The geshrat stays and when I’m King—”

“Shut up.”

“What?”

“Are your ears as bad as your eyes? I said: shut up. You’ll never be King of anything. You’re a nasty maggot-brained little nobody. You think of nothing but yourself, and the only thing you’ll ever be King of is something you’d find on the bottom of your shoe.”

“Enough, Candy . . .” Malingo said quietly. He was reaching out to take hold of Candy’s hand, but she wasn’t quite finished.

“King Turd,” she said. “That is the most you’ll ever be.”

Jollo’s hackles were rising, and he was giving off a vile bitter odor, which she hadn’t smelled earlier, perhaps because she’d been farther away from him. The acrid smell made her eyes water, and it was that fact more than Malingo’s summons that made her give up telling Jollo what she thought of him. She didn’t want him to have the satisfaction of believing he’d reduced her to tears so she turned her back on him and went to catch hold of Malingo.

The smell of Jollo’s rage suddenly became a lot stronger, and she knew without looking back that the little monster was right behind her reaching up to dig his claws into her neck. But that was another satisfaction he wasn’t going to get. She didn’t have time to grab Malingo’s hand. She just leaped off the jetty and into the boat, falling facedown in the stale water that had collected at the bottom. By the time she got up, Malingo had already gotten the oars in the water and was rowing the boat away from the jetty where Jollo B’gog was still standing, bristling and spitting, his wads of spittle expelled with such demonic force that they could be heard as they hit the stern of the boat.

That, however, was the worst he could do, at least for today. Perhaps tomorrow he would get his throne and crown. Stranger things had happened. Until then Candy would remember him as a frustrated brat standing on an antiquated jetty, spitting and spitting, until his target was out of range.

As soon as Malingo’s rowing brought the boat clear of the boy’s protection, it was collected by a current of surprising swiftness, which carried them off. The current moved with the speed of an instructed messenger, carrying the boat through a tunnel that in no way resembled the cavern through which they’d entered. It curved sinuously, first left, then right, then left again, the motion almost hypnotic. As she was rocked in the cradle of the boat, Candy allowed herself a moment of happiness.

I got rid of her, she thought to herself. The bitter monster who was in my head, killing my joy, has gone forever. And I’m a little different, maybe: but I’m still Candy Quackenbush, the way I always was.

“You’re smiling,” Malingo said. “It’s because she’s gone, isn’t it?”

“You know me so well,” Candy replied.

“I like that. Knowing you. It’s the best thing that ever happened to me.”

“And from now it’s going to get better and better,” Candy said.

They said no more, but lay content in their well-earned fatigue, as the boat moved on through the long, winding cavern, until its waters brought them out into the waters around Jibarish, which lay calm under a sky so bright with stars that they could see to the mists where this Hour faded and became another.

“Where now?” Malingo asked.

Part Three

Many Magics

The magic of the circle,

The magic of the eye,

The magic of the vortex,

The magic of the cry.

The magic of the head bone,

The round which bounds the mind,

The coin of gold which buys the bait

The ouroboros will find.

The worm surrounds the human heart,

Our hearts surround the world;

And sleeping, in the beating womb,

The naked babe is curled.

Chant your courage round the child,

Make joy its root and rhyme;

And we, my love, will wander freed

Of Loss and Fear and Time.

Chapter 20

Tomorrow, Today

AS IS TRUE OF all prophets, the prediction merchants of the Abarat were egotistical and combative, contemptuous of any other seers besides themselves. The fact that each of them worked in radically different ways to achieve their results only intensified the antagonism. One might see signs of futurity in the eighty-eight cards of the Abaratian tarot; another found his own vision of tomorrow in the dung of the yutter goats that grazed the golden fields of Gnomon; while a third, having witnessed the way the music of a Noncian reed pipe had induced the lunatics in a madhouse on Huffaker to dance, had then discovered evidence of how the future would unfold in the footprints the patients had left in the sand.

Thus, separated both by their methodologies and by a dangerous sense of their own importance, none of the soothsayers ever compared their predictions with those of others. Had they done so they would have discovered that each of them—however unlike their methods—was receiving the same news. Bad news.

A darkness was coming. A vast and implacable darkness that would pinch out every star and eclipse every moon that lit Night’s skies and extinguish every sun that blazed in the Heavens of Day.

Had the prophets of Abarat put aside their vanities and self-importance when these presentments of darkness had first crept into their minds and shared their fears with one another instead of clinging to them like the lethal possessions they were, they might have avoided the tragic consequences that had come as a result of that envy and covetousness.

The tragedy lay not only in the waste of those prophetic minds, doomed to descend into madness and self-destruction, it lay in the fact that the Abarat was to be plunged into a waking nightmare that would change it forever.

Chapter 21

Boa at Midnight

BOA AND THE SNAKE, finding they both were of royal blood, parted amicably. And, rather than waste any more time with Laguna Munn or her sorry excuses for children, Boa fled Jibarish for Gorgossium. Something became apparent to her as soon as she set foot on Midnight’s earth: Gorgossium had changed. There was a new urgency about the island that she couldn’t remember ever sensing when she’d come here before. At the Todo Mines there was a steady stream of miners, thousands of Abaratians of every species from every island, some marching down to work in the open seams, which were illuminated by banks of lights fiercer than the noonday sun on Yzil, while other gangs of workers—many among them members of the Kooth nation, whose four huge eyes naturally produced strong beams of parchment-yellow light—were crowding into iron elevators, each big enough to carry two hundred workers, so as to be taken to work in the labyrinth of tunnels below. The noise of drilling and cursing and blasting made Boa’s head throb. She’d overtaxed her new body with the demands of the Sepulcaphs. It wouldn’t be an incantation she’d be using again any time soon.

Away from the mines she headed toward the forest of Ancients, trees of half wood, half stone. They were massive pillars that kept her from seeing her destination—the thirteen towers. It was there that she encountered further evidence of Gorgossium’s furious new appetite. A large group of merchants, who’d been traveling ahead of Boa by a half mile or so, had been attacked by a number of Corruption Flies, the form and color of which was exactly that of the flies Boa had seen crawling on rotted food in the alleyways of Chickentown, except that Gorgossium’s species were the size of cars.

She didn’t have to wait until the last of the merchants had perished to get past the place where the flies had found them. While the screams of those being plucked up and carried away was still going on, a wave of Old Red, which was the islanders’ nickname for the crimson mist that curled around the island like a gargantuan scarlet snake, appeared nosing its way between the stone-still Ancients. She cursed it under her breath. She had no choice: enter the mist, which wasn’t a pleasant thought, or contend with a pestilence of agitated Corruption Flies.

More than once Carrion had teased Boa by telling her that he knew of references in the Abarataraba, the most rare and powerful magical work of the Hours, concerning the true nature and purpose of Old Red. She wanted to know the details, but Carrion had refused to share what he knew.

“In time,” he’d said.

That had always been a favorite trick of his: putting off telling the juicy stuff until later, always later.

Well, later was here. She wanted knowledge and she would have it, even if it meant stepping into the skin of Old Red itself. She didn’t let her unease slow her down. She plunged into the churning mist and kept walking. Rather than allow her mind to dwell on her fears, she kept her thoughts on the future. She would have to be careful from now on. She had lived beneath the mask of an innocent Princess when she’d been here before. She no longer had such cover. Word of what had transpired on Laguna Munn’s island would surely have reached Gorgossium by now. And given that her rise to power in Carrion’s world had meant that others, who had doubtless expected to be elevated long before her, had seen those dreams dashed, there would be many here at Midnight who would gladly see her dead.

Carrion had been a man on the rise when she’d carefully orchestrated their “accidental” meeting. He had quickly made it plain to her that his ambition was almost limitless. He intended to go everywhere, know everything, and have knowledge of every state of being. She knew a man destined for power when she saw one.

Word was that he’d perished in the Chickentown fiasco. And she’d seen him, through Candy’s eyes, carried away by the Izabella, and lost in the flood that had overwhelmed Chickentown, but she could not bring herself to believe that he was dead. He had been badly injured, no doubt. But he’d been wounded many times before, often grievously, without forfeiting his life.

No. Her precious Christopher, who had taught her so much, was alive. She was certain of it. Somewhere she would find him. And somehow they would mend what had been broken between them.

The clammy folds of Old Red thinned and parted, and through its bloody veil Boa could see one of the towers ahead. She was almost there! The tower was being worked on, she saw, the old stone being replaced with polished plates of quamighto in the silvery surface of which reflected objects were fantastically distorted.

Despite her exhilaration at knowing she would soon be in Carrion’s presence she couldn’t help but feel a twinge of unease. If Carrion was indeed alive, and had come back to Gorgossium—where else would he go?—then she was perhaps but a minute or two from being in his presence. She brought an image of him into her mind’s eye. That almost naked head, with barely sufficient flesh to stretch over his jutting bones, and the two pipes that had been surgically implanted in the back of his skull, causing his nightmares to be siphoned off out of his brain and swim freely in the fluid that he breathed, allowing him to live in the company of his own darkest vision. But for all that was monstrous in his appearance, there was a tenderhearted creature within.

And she had betrayed that tender heart. She had used him for her own advancement as a magician, and then cast him aside to marry Finnegan Hob. For that crime against love, Carrion had hired an assassin to murder her at her own wedding. So, they were evenly matched. A heart for a life. Who could argue with that? They’d both paid terrible prices for what they’d done. If she could persuade Carrion of that—if she could make him understand that it was time to forgive and move on—then perhaps there was a chance he could forgive her betrayal. Words of love would no longer suffice, of course. He would want her closer than words: much, much closer.

But if that was the price of winning his devotion again, of healing the hurt she’d done him, then it was a tiny price, and she would gladly pay it. And it certainly didn’t hurt her case that she was returning to him with knowledge of the Hereafter; a world she knew he had long hoped to subdue with wieldings of unimaginable scale. Now she was familiar with that idiot world. She’d studied it for almost sixteen years through the eyes of Candy Quackenbush. She had witnessed in nauseating detail how the human world worked: its rituals of comfort (television, food, religion); its appetite for poison (television, food, religion); and for the monstrous edifices of desire (television, food, religion): she understood them all. What might she and Carrion, the apprentice and her sometime master, not do if they went to work in that stupefied world with the intention of bringing it to its knees?

Oh, by A’zo and Cha:

WHAT MIGHT THEY NOT DO?

And then, as she came to the edge of the trees, Old Red dispersed completely, and Boa barely suppressed a cry of shock seeing how the scene before her had changed. She had seen only one three-spired tower through the mist. The rest had been demolished completely, their rubble removed and the ground where they’d stood pummeled flat, so as to make the size of the new tower seem even more prodigious. The spires had no windows for ninety-eight percent of their height.

Only at the top of the immense central spire, which was needle-fine, were there windows; a row of them, shaped like narrow eyes, all around the crown of the structure. As she studied it, however, she saw that there were vertical rows of symbols etched into the stone, which had the sheen of mercury. They were indecipherable to Boa, but she knew their origins. They were pieces of ancient Abaratian, the language of the Thread as it was sometimes known, meaning that it had been used to encode and connect all things beneath the Twenty-Four Hours and One that hung above the islands. In these sigils, every piece of the Abarat, from a dew drop to a mountain, from a flea to the Requiax, from a second of unendurable grief to an infant’s first smile—all written and entwined in the thread that ran unbroken through Time and Time Out of Time, connecting it all, forever and always.

But oh, she thought, what a fine and terrible thing it would be to cut that sacred cord! To sever all from all, in perpetuity and visit the despair that no prayer or calculation could cure. . . .

The thought of doing such sublime harm filled her with joy. A Princess capable of such ambition was inviolate. She had died, but lived again. No harm could possibly come to her. And, in thinking so, she stepped out from beneath the Ancients and started across the open grounds toward the Needle Tower. No one was guarding the tower for a very simple reason: it had no door. Boa circled the tower twice examining the wall for the slightest hint of an opening, however narrow or small. But there was nothing. Of course it was perfectly possible the door was concealed by a Seemi Feit, but she was in no mood to search for any trailing threads of Seemi Rope to carefully pull it apart. She was out of practice with decoding, and impatient to see what was inside the tower. So she gave her blood a charge of power by whispering three syllables—v’aatheum—against her wrist, then immediately biting into the meat, drawing off a mouthful of blood, and before it had time to dissolve on her gums and tongue, spat it with all possible force against her distorted reflection.

The reflecting seal bubbled, smoked and dissolved. She stepped inside, too curious to wait for the melt to stabilize, preferring instead to endure the sting of metal droplets on the top of her skull and on her shoulders as she entered.

Her impatience was quickly rewarded, the little hurts inconsequential compared to the astonishment that awaited her inside.

There were no stairs spiraling up the great heights of the Needle. Nor was there any kind of mechanical device to carry her up. Instead the walls of the tower were covered with elaborate growths of yellow, gray, and blue-purple tissue, which erupted into sentient blossoms of exquisite complexity and beauty, their membranes swelling and contracting, their intertwined stems flushed with speeding iridescence as they aspired to reach the moonlit chamber at the top. Very cautiously Boa reached up and touched a censer-shaped knot of multicolored matter, which hung at the intersection of several lengths of shiny-wet cord.

The Needle’s anatomy responded to the touch instantly. The ground beneath Boa’s feet rolled, and she might have been thrown down had it not instantly compensated by rolling in the opposite direction, allowing her to recover her equilibrium. She caught hold of a loop of knotted gut to prevent herself from being caught off guard again, but she had barely done so when the entire system of flowering entrails and light-bearing veins into which she had stopped began to raise her up on a platform of petal-flesh stretched over bone, rising at a breath-stealing speed, overtaking swift-seeded organs that oozed honeyed sap, and that raced ligament vines around the walls, fruited motes and glands bursting in celebration of her presence, spilling their luxurious juices upon her, staining her with their life (she, who had been a creature without form just a few hours before, expelled from solidity) blessing her with new ways to live this life After death.

She was almost at the top of the tower now, and she could see that the chamber was not only illuminated by moonlight. There were other sources of light up there as well, and they were moving.

“Carrion?” she said. There was no reply. “It’s me. It’s your Princess. I’m back.”

Being an island that saw the transportation of the living and the dead (along with many travelers who could not fall into either category), Gorgossium had need of three harbors.

The harbor equipped for the construction and launching of vessels of great magnitude was at Kythevai, in the northeast. This was the harbor from which Mater Motley’s newly commissioned warship, the Wormwood, had set forth to wreak havoc in the Hereafter, only to meet an undignified end on the flooded streets of Chickentown.

For sheer volume of vessels docked and unloaded, however, the commercial harbor at Uznak, in the south of the island, was the more important.

But it was from the third and smallest of the three harbors at Vrokonkeff, that the Old Mother was presently preparing to make her departure.

The voyage she was about to take was not of enormous length; she was merely crossing to the pyramids at Xuxux. The voyage may not have been of great consequence, but it was one of great significance, and she had prepared for it by fasting for nine days, and during that time, not uttering a single word. Even now, as she dismounted from the mummified hand that had long been her preferred mode of travel, and approached the simple vessel that would carry her to the pyramids, she did not speak. Nor, out of deference to their doyen, did the seamstresses who accompanied her.

She was half way up the gangplank when there rose a commotion farther down the quayside.

“Lady! Lady!”

It was a girl called Maratien, who for some years had attended upon the Old Mother in the tower, who came racing along the dock to speak with her mistress. Several seamstresses broke ranks to stop the girl from reaching Mater Motley for fear that Maratien’s intentions might be violent.

But the Old Mother had no fear of the girl.

“Let her go,” she instructed. “She may approach. What is it, Maratien? What’s distressing you, child?”

“There’s somebody in your tower.”

“Yes, of course. I left—”

“Not any of your seamstress sisters.”

“Who then?”

“I didn’t recognize her.”

“You were sufficiently concerned to race down and warn me?”

“Yes, my lady.”

“You do know how important this voyage is?”

“I know. Of course. And forgive me for having delayed you in your great work. I meant no disrespect. Please—”

“Ssh, ssh, ssh,” Mater Motley said with an almost loving indulgence in her voice. “You did well.”

“I didn’t think—”

“I said you did well, Maratien. And so you did. There will be another tide. I will return to the tower with you.”

“What if I’m wrong?”

“Then you will have made an error and you’ll learn from it, won’t you?”

“Yes, lady.”

“Now let’s see who has come to visit me.”

Chapter 22

Turning Away

ONCE THE SMALL ROWING boat had delivered Candy and Malingo out of the maze of caves beneath Jibarish, and into the open waters of the Izabella, it had lost all power of self-will.

“Do you have any idea of what direction the Nonce is in?” Malingo said, gazing about confusedly in all directions.

Candy considered this for a long moment. A chill wind came across the waters. She shuddered.

“I can’t focus. I’m all alone in here,” she said.

Her hand went to her face. Behind it, tears came. And once they came, could not be quelled. Malingo just sat, an oar in each hand, watching her. Though his head was dropped, he kept his eyes on her.

“I would have thought you’d be happy to be rid of her,” he said.

“I am,” Candy replied. “At least I was on the island. And she’s a vile piece of work. But still, in here . . .” She tapped the middle of her forehead with her finger. “In here there’s just me and a lot of space. Too much space.”

“Everybody’s in the same situation.”

“Yes?”

“Of course.”

“Lonely?”

“Sometimes very.”

“I didn’t realize how strange it would feel, with her gone. You’re right. I’m just feeling what everybody else feels.”

She wiped the tears from her cheeks with the heels of her hands, but she’d only just done so when her sorrow overwhelmed her again and more tears came. It was as though she, Candy, was weeping for the first time, without another presence in her thoughts to help her shrug off her grief. She didn’t try to stem the flow now. She just let the tears come, talking through them.

“I thought there was enough of the real me just spread out to fill my head. That’s how it felt at first.”

“And now?”

“Now it’s like I’m sitting by a little fire in the middle of . . . in the middle . . .” The tears almost silenced her, but she pushed on through them. “. . . the middle of a huge gray nothing.”

“Is it solid? The gray, I mean.”

“Does it matter?” she said, looking out over the dark waters.

A single squid, its body no longer than her foot from the tips of its tentacles to the top of its head, propelled itself past the boat, its body decorated with waves of color.

“Maybe it’s just a gray mist,” Malingo said. “Maybe it’s not empty. Maybe it’s full of things that you just haven’t seen yet.”

Candy glanced up at Malingo, who was studying her so intensely, his face so full of love she could feel its presence, a living thing, coming in to drive off her solitude. Whether he intended it or not, that’s how she felt.

“I hate girls who cry at every little thing,” she said to him, wiping her tears away for a second time, “so no more blubbering from me.”

“It’s not as if you didn’t have a reason,” Malingo replied.

“There’s always reasons, aren’t there? I’m sure all kinds of things will go wrong before I get home.”

“Back home to the Hereafter? Why go back there? You said you hated it.”

“It wasn’t that bad,” Candy replied without much conviction. Then, looking back at the sea, she said, “I love being here, Malingo. Nothing would make me happier than to stay forever.”

“Then stay.”

“I can’t. The price is too high.”

“What price?”

“People’s lives. Not just Covenantis. But Mrs. Munn . . . she was almost killed too. And there’ve been plenty of others. Some of them perhaps you’d say deserved it. Kaspar Wolfswinkel. The Criss-Cross Man. A lot of stitchlings on the Wormwood, and Mater Motley’s seamstresses. All of them would still be alive if I’d stayed in Chickentown. What just happened with Laguna and her boys is the last straw.”

“And what about the other ones whose lives you’ve changed? The people who love you? What about me? What will I do when you’re gone, Candy? I thought we were going to be friends forever.”

Candy sighed.

“You’ll come visit,” she said.

“I’m sure I’d be very welcome in Chickentown,” Malingo said. “They’d probably put me in a zoo.”

“But suppose something were to happen to you right here, because of me? You know it could. I couldn’t live with that.”

“Nothing’s going to happen to me, I swear. I’m going to live forever. We both are.”

“Oh, and how long have you had this planned?” Candy said.

“Since we got out of Wolfswinkel’s house. I thought then: this girl has miracles at her fingertips. Nothing’s beyond her. That’s what I believed then and I believe it even more strongly now.”

“Miracles? No. That wasn’t my doing. That was Boa, staying in practice for the day when she finally got out.”

“So if you’d have come knocking on Kaspar Wolfswinkel’s door without Boa—”

“We’d both be slaves right now.”

Malingo shook his head.

“You’re wrong. I remember very clearly looking in your eyes that first time Wolfswinkel summoned me.”

“You were hanging upside down from a roof beam.”

“That’s right. And I looked in your eyes—I remember this so, so clearly—and you know what I saw?”

“What?”

“Exactly the same person I’m looking at right now. Candy Quackenbush, of Chickentown, Minnesota. Come to save my life—”

“But—”

Malingo raised a finger.

“I’m not done yet,” he said. “You’d come to save my life from the hell Wolfswinkel had turned it into. Maybe you didn’t realize that was what you’d come to do, but it was. Now you can make lists of people who got hurt because you crossed over from the Hereafter, but I can make just as many lists of people who are still alive, or whose lives are better, because of you. Think of all the people who lived in fear of Christopher Carrion. You took that fear away.”

“Did I? Or did I just leave room for something even worse to take his place?”

“You talking about Mater Motley?”

“For now. But there’s probably somebody out there even worse, whose name we don’t even know yet.”

“You’re right. The Abarat’s got its share of bad. Just like the Hereafter, right?”

“Right.”

“But you didn’t put them here. Can you really blame yourself for every twisted, poisoned soul in the Abarat?”

“No. That’d be stupid.”

“And you’re not stupid,” Malingo said. “You’re anything but. Even if you were to leave right now the Abarat would never be the same. There’d always be this brief, golden time we’d remember. The Age of Candy.”

That broke Candy’s dark mood, at least for a moment.

“The Age of Candy!” she laughed. “That’s the silliest thing you’ve ever said.”

“I thought it had quite a poetical ring to it,” Malingo replied. “But if you think it’s silly then there’s only one way to stop us all from making idiots of ourselves.”

“Which is—”

“You can’t leave. Simple as that.”

Candy’s laughter died away and she thought about things for a long while. Finally she said, “I tell you what. I’ll stay until this whole business with Boa is cleared up. How’s that?”

“It’s better than you leaving us right now. And of course there’s a possibility that the mystery of Princess Boa will never be completely solved. In which case you’ll just have to stay with us forever.” He grinned. “What a terrible thing that would be.”