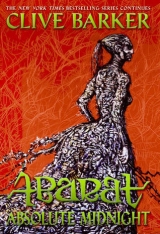

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“And it will be the same with Commexo City?” Maratien said.

Mater Motley made a snort of contempt as she strode toward the mosaic of the island of Pyon, and set her foot upon the spot where Rojo Pixler had built Commexo City.

“The stars no longer shine over Pyon,” she said, “but the city still burns as brightly as ever.”

“Is Pixler there?”

“Why would he not be?”

“He went down into the Izabella.”

“So he did. An odd coincidence. Something vast happens in the heavens, and Pixler is down in the deep . . .”

“I heard a rumor,” Maratien said.

“Go on.”

“That he came back, but he’s not himself.”

“Really?”

“Yes. He supposedly went in search of a Requiax. Those don’t really exist, do they?”

“Everything exists at some depth, Maratien.”

“Everything?”

“Yes. Everything,” the Hag replied. “Perhaps he’s come back suffering from deliriums of the deep.” She took one of the needles from her dress; needles forged in cold fires that Zael Maz’yre itself had called up. She gave the needle to Maratien. “Take this down to General Axietta. You know which of the women she is?”

“She’s the bald one with the birthmark?”

“That’s her.”

“She’s beautiful,” Maratien said.

“Well you take the needle down to her as proof that these orders came from me.”

Maratien took the needle.

“What orders, m’lady?” the girl said.

“She’s to take four warships, with six legions of stitchlings in each vessel. Head straight for Pyon. There’ll be plenty of distraction to keep Mr. Genius Pixler from expecting an attack from the sea. When she gets into the city she’s to take it—destroy it if she’s in the mood. I don’t care. But there are two things I need her to do without fail.”

“Yes, m’lady?”

“Kill every light that burns in that damn city. And make it her personal business to bring me back the heads of Rojo Pixler and the boy.”

“The boy . . . ?”

“The Commexo Kid.”

“Is he a living thing?”

“We won’t know until we have his head in our hands, will we?” Mater Motley said. “Now go. I want Commexo City dark in two hours.”

Chapter 37

Love and War

MATER MOTLEY WASN’T THE only one who had a comprehensive view of the sacbrood’s advance over the Abarat. At the heart of the Commexo Company’s headquarters, in the Circular Room, reports came in from the innumerable mechanical spies, perfect copies of species from the tiny tiger tic to the enormous Rashamass (which resembled a cross between a whale and a millipede). They weren’t programmed to seek out events of any great moment. But there were so many of Pixler’s spies out in the world that at any given Hour one of them would be certain to catch witness of a scene of tragedy or celebration, were it to occur.

But in all the years the cyclopic Dr. Voorzangler, whose genius with Abaratian technologies was responsible for making Rojo Pixler’s visionary dreams into practical realities, had traveled the immense circle on one of the gravity-negating discs that carried him wherever he willed them to take him, he had never witnessed anything as momentous as the events unfolding on the screens now. He had watched as the pyramids at Xuxux had been unsealed, silently awed—though he would never have admitted it—by the sheer power of the hidden engines that had opened the pyramids up. But their opening had only been the first part of the spectacle. What followed had been more incredible still: the outpouring of a life-form Voorzangler was not familiar with, that had been hidden away in the tombs, and now rose like six black rivers flowing heavenward, where they converged to become a sea of darkness that spread over the sky and above the pyramids, blotting out the constellations above Xuxux then moved outwards: east toward Babilonium, south toward Gnomon, west toward Jibarish, and north toward the island of Pyon, at which Hour, of course, Commexo City stood.

Voorzangler surveyed the sight for a few minutes, trying to get a grasp on what he was seeing, then he summoned his assistant, Kattaz to his side.

“What’s Mr. Pixler’s status?” he wanted to know.

“I was just with him,” Kattaz replied. “He says he feels fine after ‘the problem.’ That’s what he calls it, sir. The little problem with the bathyscaphe.”

Voorzangler shook his head. “Really, the man is fearless. We nearly lost him . . .” He stared at the spreading darkness again. “I’m going to start making a report on this . . . this phenomenon. I’d like Mr. Pixler to see it for himself when he’s feeling well enough. Would you inform him that we have a very immediate problem? This . . . darkness is going to cover the city within the next ten minutes.”

“What is it?” Kattaz asked him.

“According to my records this is a species, I believe they are sacbrood. They predate Time, and therefore these islands. But what we know of them from fossil records suggest that they were significantly smaller than these creatures we see now.”

“Genetically altered then?”

“That’s my assumption.”

“By science? Magic?”

“Possibly both. Look at them!”

He directed Kattaz’s attention to the screen behind her. One of the creatures reporting this cataclysm, a balloon fox, had risen dangerously close to the sacbrood, risking its existence in order to report every detail of what it was witnessing. The sacbrood were a study in diversity: no two of them were alike. Their heads were complex arrangements of black, insentient eyes, which were sometimes assembled in glistening bunches like ripe fruit. Some had immense barbed jaws, some complex arrangements of mandibles. Some had heads that almost resembled that of the common Hereafter housefly, which had quickly established itself in the Abarat having come between worlds in the early years of trading.

“Oh by the Kid! Look at this, Doctor Voorzangler! This one . . . the eggs it’s carrying! That’s disgusting. Lordy Lou, look at all those little maggoty . . . oh, that’s horrible.”

“Do you really think so?” Voorzangler said, looking at the image with a detached curiosity. “It’s just more life, isn’t it? We can’t be judgmental. At least I can’t.”

“Well, I’m sorry, Doctor. You’re probably quite right. It’s just another species.”

She was about to say more to him when the door to Rojo Pixler’s private chamber opened and the great architect appeared.

“What’s going on, Voorzangler?”

“I was just about to alert you, sir.”

“No need. You’re being watched too, remember?”

“I wasn’t aware—”

“That some of the screens you’re looking at are looking at you?”

“Yes.”

“Well, they are.”

He closed the door to his suite behind him and then, moving very slowly, his limbs exhausted, he stepped up onto one of the discs and, taking up his familiar posture, hands cupped left in right behind his back, he allowed the disc to carry him the long way around the room, examining the screens as he went.

Such was the immensity of the chamber, and vastness of the numbers of screens, that it took him several minutes to come around again to the place where Voorzangler and Kattaz were standing. When he finally did so, and Voorzangler got an opportunity to look at his mentor very closely, he was troubled. Pixler appeared very much the worse for wear following his descent into the depths of the Izabella. His skin was white, and beaded with sweat. His hair was pasted to his scalp with the moisture.

“I wish you’d let me examine you, sir. Just a brief checkup?”

“I’ve told you, Voorzangler, I’m perfectly fine. Never better.”

“But weren’t you in the bathyscaphe when the Requiax took hold of it?”

“Oh yes. Oh, I’ve been closer to death than I ever care to be again. But the Requiax is an ancient entity, Voorzangler. It has no interest in whether a man lives or dies.”

“You’re not a man, sir. You’re Rojo Pixler. You’re the father of the Commexo Kid.”

“Yes. Yes, I am. And I am not going to die. Now, or ever.”

“Or ever, sir?”

“You heard me, Voorzangler. Or ever. The future is mine to own. It’s bright, Voorzangler, and full of possibilities. I can’t afford to die.”

“I want to believe you, sir—”

“But—?”

“But these sacbrood, sir . . .”

“Is that what they are?” Pixler said matter-of-factly. “Fascinating.”

“Our records report—”

“Forget the records. They’re not worth a damn.”

“But sir, you wrote them.”

“No, not me, Voorzangler. I was another man entirely when I wrote those. That man is gone.”

“Gone, sir?”

“Yes, Voorzangler, gone. As in departed. Exited the building. Dead.”

“You look a little sick, sir,” Voorzangler said, speaking slowly, as though to an idiot. “But . . . you’re not dead. Trust me.”

“Oh no. Thank you very much for the invitation. But I don’t think I will. Trust you, I mean. I have better advisors now.”

“Sir?”

“It’s their understanding that our neighbors on Gorgossium, specifically that she-cur, Motley—” As he spoke of her, his features were overtaken by a rising wave of infiltrations, his muscles twitching violently, plainly not under Pixler’s command. “She’s apparently intending to cut off all natural light to the islands.”

“How do you know this?” Voorzangler said.

“I’m looking at the screens, Doctor. This mass swarming of sacbrood is blotting out the skies. There will be a severe, even catastrophic, drop in temperature. Blizzard conditions on islands that have never seen a flake of snow. Crops will perish in the fields. Livestock will freeze to death. There will be massive loss of life in rural areas—”

“People can build fires,” Kattaz said.

Pixler looked at the woman with naked disdain. “Go away,” he said. “You offend me.”

“Why?”

“I don’t need reasons. Just go.”

“Mr. Pixler, please.”

“Oh don’t whine, Voorzangler. I know what goes on between you two. I’ve watched you fawn over her. Love makes you look ridiculous, don’t you see?” He glanced back at Kattaz. “Are you still here? I said go away.”

Kattaz looked to Voorzangler for help, but his face was utterly blank, all sign of real emotion concealed. She didn’t wait for him to come to her defense. Obviously he wasn’t going to do so.

“I’m sorry I offend you . . . sir,” she said in a monotone, and departed.

“So Mater Motley has herself an army,” Pixler went on, as though nothing had happened.

“She does?” Voorzangler said. His gaze was on the screens filled with sacbrood now.

“Stop looking at the damn insects. They’re just a part of what she’s up to. Look at this.”

He pointed to a cluster of screens showing both recorded footage of the stitchling legions, marching in shockingly precise lockstep as they assembled to board the warship, and live feeds showing those same warships carving their way through the dark waters of the Izabella; the only light supplied by the lamps, like blazing eyes, in the bows of the ships, and a host of smaller, airborne lights that cast a cold, blue-white luminesence as they flew around and above and behind the vessels.

“You mean the goons on the ships?” Voorzangler said. “They’re just stitchlings. Rags and mud! They have no brain-power. Yes, she can train them to march, but I doubt they’ll do much else!”

“I think perhaps she let you see the clowns so that you wouldn’t ever think of them as soldiers. The Old Mother’s quite brilliant in her way, you know,” Pixler said.

“The Old Mother? Is that what they call her? Huh. She’s a crazy hangover from the days of the Empire. I doubt she even knows what year this is.”

“She may indeed be touched by madness, Voorzangler. On the other hand, that may be simply a performance, to have you believing she is harmless in her lunatic condition.”

“Sane or insane,” the doctor said, “she is not the real power. That was Carrion right from the beginning.”

“Never underestimate a woman. After all, Old Mother has persuaded some very powerful allies to come over to her side. Powers I do not even care to name. They do not see the world as we do, in opposites. Night and Day. Black and White.”

“Good and Evil?”

“They would find that particular idea utterly absurd.”

“So these . . . beings . . . are her allies?”

“So she believes.”

“But you don’t.”

“I believe she is useful to them at present. So they indulge her dreams of founding an Imperial dynasty—”

“Isn’t she a little old to be having children?”

“You don’t have to give birth to children in the world of mysteries where that woman walks.”

“I see.”

“No, you don’t. Not remotely.”

“No. No, I don’t.”

“Good!” Pixler said brightly, laying a clammy, cold hand—a dead man’s hand was all Voorzangler could think—on the doctor’s shoulder.

“You can still admit to ignorance. There’s hope for you yet, Voorzangler. Smile, Doctor!”

“I can’t. I mean I will if you want me to . . .”

He tried to fake a smile, but it was a wretched sight.

“Forget it,” Pixler said.

Voorzangler let the smile die a quick death, and went on talking: “Is the City in any danger?”

“Well, ask yourself: what do our sources tell us about her plans?”

“That she wants the Abarat in total darkness.”

“But . . . Commexo City is still lighting up the sky.”

“Exactly.”

“So maybe we should placate her? Offer to dim them, maybe fifty percent? Just until she sends her warships home?”

“That won’t fool her. We have to stand our ground or she will destroy this city and all that it’s about to become.”

“Which is what . . . ?”

“It’s a conversation for a night without warships, Voorzangler. Go down to the dormitories. Speak to that milk-and-cookies woman.”

“Mrs. Love.”

Pixler looked appalled.

“Who in the name of all that’s addictive called her that?”

“. . . um . . .”

“I take it from your gormless expression that I did.”

“Yes.”

“Well, we’ll fix it when this Last Great War is over and we’ve won the peace.”

“You sound very confident, sir.”

“Do I have any reason not to?”

“Wars are unpredictable, sir. We didn’t know Mater Motley had an army of stitchlings until a few minutes ago. And . . . there’s the matter of her allies.”

“The Higher Powers,” Pixler said.

“We have no idea who they are, is that right?”

“Put it this way. If I had some knowledge of them I’d tell you. Not the knowledge. Only that I knew it.”

“You don’t trust me any longer, do you?”

“Oh, Lordy Lou, Voorzangler. I never trusted you.”

“What? Why?”

“Because you think too much and you feel too little. And that can bring Empires down.”

Voorzangler studied the ground between his oversized feet for a long moment. “If I may remark, sir . . .”

“Remark away.”

“I feel something for Kattaz. Something very real. At least I believe it’s real. And it may seem foolish in a one-eyed, obsessive-compulsive scientist of advancing years to hold out hope for some return on my investment of devotion, but if it’s foolish, then so be it. I stand by my feelings, however much a fool I may be.”

“Huh.”

Now it was the architect who looked away, staring at the screens without seeing them. When he looked back at Voorzangler, there had been a subtle shift in his features. Though he was still Rojo Pixler, something else—the same force, perhaps, that had infested his face with twitches—was present in him. It leaked a tiny amount of black fluid through his pores into each bead of sweat, so that they decorated his blood-drained features like immaculate black jewels.

Or, Voorzangler thought, like the eyes of the sacbrood.

“You know, just a few minutes ago I had decided I was going to put an end to you, Voorzangler.”

“An end to me. You mean . . .”

“I mean I intended to kill you. Or more correctly, have you killed.”

“Sir? I didn’t realize you had such a poor opinion of my performance.”

“Well, I did. But I’ve changed my mind. Your love saved your skin, Voorzangler. If you hadn’t admitted to that, I’d have had you arrested and you’d have been dead two minutes later.” He studied Voorzangler as he spoke, with a kind of detached curiosity. “Tell me how that makes you feel,” he said. “Just tell the truth. Nothing fancy required.”

“I suppose I’m grateful. I’m a fool.”

Pixler seemed satisfied with this.

“There are certainly worse things,” he said, apparently speaking from a profound fund of knowledge. “A great deal worse. Now go and tell Mrs. Love to wake the Kid. Go on.”

With a thought, the doctor had his disk on the move, dropping away from the high screens that he and Pixler had been viewing, and calling after Voorzangler as he descended: “And be grateful you’re a fool, Voorzangler,” he yelled. “You get to live another night.”

Chapter 38

An Old Trick

WITH THE JOHN BROTHERS at the helm of The Piper, the harbor at Tazmagor was soon out of sight, erased by the sea spray that was thrown up by the waters of Mama Izabella. Candy went into the boat’s wheelhouse and consulted the very old charts—all of which were covered with notes about where the boat’s owner had been successful in finding schools of ninkas, fool fish, and even the triple-beaked, ten-tentacled decapi.

“You know what?” John Fillet said.

“No, what?” said John Moot.

“I think our glorious leader has taken a liking to our new crew member,” John Fillet said.

Candy kept her eyes on the chart, though there was very little information there of use.

“Don’t know what you’re talking about, Fillet,” Candy said.

“It’s not just Fillet,” John Slop said.

“We all noticed it,” said John Pluckitt.

“You can’t keep much from the John Brothers,” said John Drowze.

“It’s none of your business,” Candy said.

“I’m sorry,” John Mischief said.

“You’re all such gossips.”

“The point is—” Mischief started to say.

“The point is whatever you think you saw, you saw wrong. Lordy Lou, the boy was going to stab you.”

“So you stopped him by throwing your arms around him,” said John Serpent. “Yes, we saw.”

“I am not having any further discussion on the subject.”

She stopped and turned to look directly at what she’d seen from the corner of her eye. The Piper was plunged into a thick fog, making the end of one Hour and the beginning of another. The light continued to dim, but the darkness wasn’t black. There were shifting patches of blue and purple in it now.

“We’re going to be coming out of the other side of this very shortly,” Mischief said.

The brothers were back at the wheel now, their smiles erased. Fun time was over. Candy went to the wheelhouse windows to look for some sign of the coming Hour. But the windows were filthy with an accumulation of salt and bird droppings.

“Any sign of The Great Head?” Sallow asked her.

“I can’t see anything. But I’ll hang on tight. And you guys? Keep the gossip to yourselves in the future.”

“So we were wrong?” Mischief said with a smirk that defined his name. “You don’t like him?”

Candy left the wheelhouse without answering.

There was a ladder that brought her up to the roof of the wheelhouse, and a railing for her to keep hold of, for which she was grateful. The swell was growing with every wave. The boat reeled and shuddered.

“Mind if I join you?” Malingo called up to her.

“Of course not,” Candy yelled back. “Come on up!”

Seconds later, Malingo was standing at her right-hand side, hanging on to the iron railing as tightly as she was.

“If we’re on the right course, we should be seeing The Great Head from behind,” he said.

“In which direction?”

“Hopefully dead ahead.”

“I can’t see anything.”

“Neither can I. But the fog is thinning, I think.”

“Oh. You’re right! I see it, Malingo.” She laughed. “I feared the worst, but it’s still standing!” Candy called down to Mischief. “I see it! Off the port bow!”

Mischief cut The Piper’s engines, sensing perhaps that everyone aboard needed to have a quiet moment in order to think about what lay ahead. The powerful currents met out of the boundary of the fog and into the murky twilight in which The Great Head stood. Even viewed from behind, The Head was an extraordinary monument, the towers that crowned its cranium so cunningly designed that they seemed to rise naturally out of the structure of the skull.

A bonfire was blazing on the top of the tallest of the towers. It was not a natural fire. The flames were violet and silver and when they rose to sufficient heights they threw off lattices and other geometric forms, then briefly blazed as if being tested against the twilight sky. She watched the flames without even blinking, mesmerized.

“I think it’s sending a message,” Eddie said from the deck. “They look like sentences being written in the air.”

“Really?” said Malingo.

“He might be right,” Candy said, watching the flames closely. “Oh . . . wait. Yes. Look!”

She pointed past The Head. There was a cloud of roiling darkness laid along the horizon; its shadow, erasing all below as it advanced across the moonlit sea. The moon itself, two-thirds full, its face already touched by the seething fingers of darkness. And of course The Great Head, its huge, simple form—at least seen from behind—stoic, immovable. That was both its strength and its weakness, of course. It would not move, it could not move; and when darkness had come and gone, it would still be standing. Apparently it had occupants who lacked Candy’s faith, however. There were maybe forty boats in the vicinity of The Head all in the process of making a departure.

“What are those idiots doing?” Malingo said.

“And where do they think they’re going to go?” Candy replied.

Some of those departing had seen the approaching cloud and the sight of it had obviously made them reconsider their plans. Several boats, many overloaded with passengers, were turning around, or at least attempting to. The consequences were inevitable. Boats rocked and turned over, pitching their living cargo into the water.

There was a lot of panicked shouting and cries for help. There were some voices too, that did not express such terror and confusion. They did not shout, they sang: a great multitude of voices rising together to sing in Old Abaratian. It mattered not at all that Candy couldn’t make any sense of the words. The majestic calm in the tune reassured Candy the way her favorite Christmas carol, “Silent Night,” reassured her. She wondered if they knew the story of love being born in a stable, with shepherds and kings, and a bright star, high above, to mark the place, and for a moment, she wasn’t on a boat drifting on an alien sea as a living darkness eclipsed the moon. For a moment, she was back on Followell Street, on a night long gone, before she’d come to fear the stink of beer on her father’s breath.

“The moon’s almost gone,” Malingo said, monotone.

“You don’t sound very bothered about it,” Candy said.

“Well, what can I do about it? It’s a big cloud, and I’m a geshrat with a fish-gutting knife I got from a stowaway, which I wouldn’t know how to use properly anyway. I should give it back to him.”

“No,” Candy said very firmly. “You hang on to that. You might need it one of these days.”

“One of these days? There aren’t going to be any more days.”

“Oh, there will be,” said John Mischief. He’d climbed up to share the view. “Clouds come. Clouds go. It’s the way clouds are. You can’t rely on them. They’re too . . .”

“Flighty?” John Moot suggested.

“The very word!” Slop said.

“It’s not that simple. This isn’t an ordinary cloud. It can’t be blown apart by a gust of wind. It’s a living thing,” she protested.

“How come you know all these things?”

“Because she’s becoming a shaman,” said John Drowze.

As Candy drew breath to remark that she didn’t much like being talked about as if she wasn’t there, she heard somebody call her name. A woman’s voice. For a moment, she panicked. Boa? No. It couldn’t be. She glanced around, looking for the person who’d spoken. The brothers, meanwhile, continued to discuss Candy’s shamanic potential as though she wasn’t even there, and the tempers on both sides of the argument were becoming ragged.

“If she’s a shaman,” said Slop, “then I’m an only child.”

“He’s right,” said Fillet. “The girl’s half crazy—”

“Only half?” said Sallow.

“You underestimate her,” John Mischief said. “Yes, she’s a little unpredictable, but that’s what we need if the Abarat’s to survive.”

“She knows more than’s good for her—”

“More than she knows she knows—”

Candy? Come here.

Meanwhile, the debate raged on.

“Fillet’s right!”

“She’s a sweet girl—”

“But all that power—”

“She can’t deal with it—”

“And what if you’re wrong?”

Pay no attention to their babble, Candy, the voice said.

You’re not Boa, are you? she asked, knowing she only had to form the thought for it to be heard.

No.

Lordy Lou . . .

Please. We have very little time, Candy. You’re going to have to step away from them for a minute or two.

Step away? Are you kidding? Candy replied. I’m on a boat.

We know, another said. We can see you.

When the second voice spoke, Candy knew who she was talking to. She scanned the water looking for some sign of the women of the Fantomaya.

Leave your chatty friends on the boat. Come and talk to us.

Where are you?

Fourteen paces off the stern. Come to us, Candy. Quickly. Mater Motley’s seamstresses are after us. They’re riding fever wheels, and they’re moving fast.

What’s a fever wheel?

If you see one you’ll know and if you don’t then you’re blessed not to have the sight in your head.

Now that Candy knew where to look, she saw Joephi and Mespa. They appeared to be simply standing on the swell, illuminated by a light in the water that surged and then waned again in rhythm with the waves. Even at this distance Candy could see that the journey had taken a considerable toll on them. Their robes were dirty and tattered, and their faces and arms bloodied.

Come on, Joephi said, beckoning to Candy.

I can’t walk on water.

Yes, you can, Mespa said. Have faith in yourself.

I’m going to sink.

Faith. Hurry!

She turned back toward Malingo and the John Brothers.

“I’ll be right back,” she said to them.

Then she climbed down the ladder. Legitimate Eddie was staring up at the bizarre bonfire blazing on top of The Great Head.

“There’s one of them up there,” he said.

“One who?”

“One of the eight. Gan Nug!”

He pointed and Candy looked up at the Head to see that there was indeed a tall creature there, his stylish clothes, high-coiffed hair and reptilian wings garishly lit by the pyre he tended.

“Any idea what he’s doing?” Candy asked him, keeping up the same casual tone as she clambered over the side of the boat.

“Calling something up, I dare say,” Eddie replied. “From the depths.”

“Wait! Wait!” Gazza said. “What are you doing? Where are you going?”

She looked up at him. The light from the swaying lanterns made his face seem to shift, the only steady thing his immense gold eyes.

“There’s some friends of mine I need to talk to.”

Gazza looked out across the Izabella.

“Are those women walking on water?”

“Lordy Lou, you ask a lot of questions. Yes.”

“Witches?”

“I suppose so.”

“You’re one as well, are you?”

“Not really. I’m learning, but—”

Are you coming, Joephi said, or are you just going to flirt with the boy?

“They say you’re a boy.”

“The witch women?”

“Yes.”

“If you want to talk to Candy,” he hollered, his voice echoing off The Great Head, “then come to the boat!”

Come, Candy. Or if the boy has your heart, don’t. Just make up your mind.

“I’m coming,” she murmured, and set her foot on the water.

She tested her weight on the frothy water. The news wasn’t good.

My foot’s sinking!

“You’re going to drown!” Gazza yelled. “Get back up here.”

Are you barefoot? Mespa asked.

No, you didn’t say anything about—

Isn’t it obvious? It’s you who’s walking on water, not the shoes.

All right! No shoes.

She headed back to Gazza.

“Hold my hand.”

“Finally, some common sense!” he said.

“Don’t get excited. I’m just taking my shoes off. Keep hold.”

“I’m not letting go.”

“Oy. They bicker like man and wife,” said Eddie.

“All right. I’ve just . . . got to . . . got to get . . .”

The sentence came out in fragments as she struggled to get the shoes off her feet, attempting not to lose them as she did so. She liked the shoes. They were Abaratian: iridescent blue, with little animals performing on them in a shoe sky circus. But it was an awkward maneuver to reach over Gazza’s arm to get her fingers under her shoe to keep from—

Her left shoe slipped off and dropped into the water with a palliative plop. It sank instantly. The other shoe came off more easily, and for a few seconds, the last gleam of the smothered moon caught the animals prancing upon that perfect blue that no sky had ever been. She tossed it on deck.

“There,” she said to Gazza. “I’m ready.”

Then get on with it, Mespa said.

Candy let go of Gazza’s hand and walked back to the ladder, despite his protests. She set a naked foot, the left, down in the water. No, not in the water, on it. The surface wasn’t entirely solid, but certainly enough to support her. She glanced up. Malingo was looking down at her.

“Tell me you’re not going to walk!”

“Well . . . I’m a horrible swimmer,” Candy said, “so . . . yes!”

“You’re crazy.”

“That’s what I’ve been telling her,” Gazza said.

She suddenly felt the water that had supported her foot softening.

Don’t listen to doubt, Candy, Joephi said. All great things come of paradox.

“Don’t worry,” she said to Malingo as she took a breath and drew her gaze away from his disbelieving face.

“I’m not going to drown, Malingo. I’m not!”

“You can still turn back.”

“No. I can’t, Malingo. You know I can’t. I’ve been preparing for this test since I arrived—No—since I was born.”

“Utterly insane. The girl is . . .” Mischief muttered as he and the brothers joined Malingo in watching.

“I heard that,” Candy replied.

Forget them, Mespa said. This is when you prove your right to make history or drown in the water you want to walk on. You can. You are answerable only to your greater self, which in turn answers only to Creation.

She looked down at the foot that was going to take the step. If the Old Woman was to be unseated from the throne of the Midnight Empire then Candy had a part to play in that unseating. That, she understood. And if she was meant to play that part, she had to walk on water, and walk on water she would.

“I . . . am . . .” The water bore her up. “. . . going . . . to . . .” Yes! She could do this. “. . . walk!”

It isn’t a dream. It isn’t real. It’s just your mind and Creation thinking together. Walking together.

You make it sound so simple, Candy said.

It’s easier than drowning! Joephi said.

I’m not going to drown.

Then what?

I’ll walk!

And so she walked. It wasn’t as difficult as she’d expected. Every now and then she felt an eddy move against the sole of her foot, which was a little unsettling, but otherwise it was like walking on sand dunes: the rises gentle, the descents steeper. She kept her eyes on Mespa and Joephi all the way, and very soon she was close enough to see that the women were standing at the center of what appeared to be a vast spiral of fish: fish with luminous anatomies, some blue, some scarlet, some turquoise or gold.