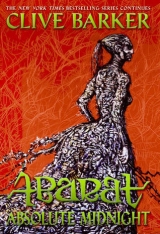

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Mrs. Munn’s half-opened hand was now in front of Candy.

“Take it!” Mrs. Munn said. “Just do it!”

“Take what?”

“Whatever you see in my hand.”

“It’s empty.”

“Look again. And be quick.” Candy was aware of Boa’s shape rising up behind Mrs. Munn, and beating at the air above her. “I can’t hold her off for long. The power in her!”

Candy could hear Boa calling to her as she beat at the Air Armor the incantatrix had put up to keep her from finishing the chase. The Armor, a conjuration Candy knew of but couldn’t wield, made Boa’s voice slurred and remote, but Candy could still comprehend enough to know what Boa was doing. She was trying to sow seeds of doubt in Candy concerning Mrs. Munn.

“She says you’re crazy,” Candy said.

“She’s probably right,” Laguna Munn replied. “Did she make you want to vomit when you saw the Sepulcaphs?”

“Is that what they’re called? Yes. It was horrible.”

“If she tries it again, you run, put your eyes out, bury your head in the ground, just don’t look at the patterns. If she’s strong enough to keep them in her skin, which she is, she can make you puke yourself inside out.”

“That’s . . . that’s not possible. Is it?”

“I’m afraid it is. She almost had me doing it two minutes ago, up the hill. Me? On my own rock! Where she got power to wield Sepulcaphs is . . .” She shook her head. “. . . unbelievable.”

“She was taught by Christopher Carrion.”

“Interesting. And of course the question remains: where did he get it? The Hereafter doesn’t have power. That’s why you did business with us. But even the Abarat doesn’t contain wieldings that powerful.”

There was a sharp stinging sound, as more pieces of the Air Armor behind Laguna Munn shattered beneath Boa’s assault.

“Lordy Lou. How did you ever live with her?”

“She wasn’t like this.”

“Or she was and you suppressed it.”

“Huh. I never thought of that.”

“No wonder you were a dull little batrat of a child. All your energy was going into keeping this monster from breaking out.”

“Who said I was a dull little ratbat—”

“Batrat.”

“—of a child?”

“You did. Who you are is the stone on which you stand. Now no more—”

There were two more brutal stings in quick succession. Then another three.

“She’s breaking through. Take your weapon!”

Once again she was offering her hand to Candy, and once again Candy was seeing nothing but an empty palm. There was a desperate urgency to the problem. Boa and her nauseating Sepulcaphs were a cracked plate of air away.

“Look again!” Mrs. Munn insisted. “Look away. Clear your head. Then look again. It’s right there!”

“What is?”

“Whatever you want.”

“Like a poisonous snake?”

She had but to ask, and there it was in Mrs. Munn’s hands: a seven-foot-long snake, its colors—a toxic yellow-green with a band of glistening black running along its length—designed to tell anyone that it was a venomous thing.

“Good choice, girl!” Mrs. Munn said, in a tone so ambiguous Candy had no idea whether she was serious or not. “Here! Take it!”

She tossed the snake at Candy, who, more out of instinct than intention, caught it in both hands.

“Now what?” she said.

Chapter 17

Snake Talk

JOLLO?”

There was no response from the wizened figure on the ground. His eyes were closed, and his pupils were motionless behind his gray, papery lids. Malingo kneeled down beside him, and spoke to him again:

“Are you still there?” he asked.

For several seconds there was no response. Then his gummy green eyelids opened and he spoke. His words were slurred, his voice watery.

“I’m still here. I just needed to rest. Everything was too noisy with my eyes open,” he said.

Malingo glanced up at Covenantis, hoping he’d know the significance of Jollo’s confusion of senses, but Covenantis’s focus was neither with his brother nor Malingo. Covenantis was turned away from his brother in the direction of the sound of—

“Shattering air,” Covenantis said.

“I didn’t even know air could shatter,” Malingo said.

“Glass can be poured like treacle if it’s hot enough. Did you not know that either?” Covenantis replied. “Are all geshrats so stupid?”

The noise came again. And again. Malingo was now looking in the same direction as Covenantis, curious as to what shattered air looked like. Suddenly, Jollo seized hold of Malingo’s arm, first with one hand then with both, pulling himself up into a sitting position, his eyes opening wide.

“She’s there,” he said, staring with eerie accuracy in precisely the same direction as his brother.

Malingo didn’t need to ask Jollo of whom he was speaking. There was only one “she” in the boys’ universe. And all Jollo wanted right now was the comfort of her presence.

“Mama . . .” said Jollo. “Find her, Covenantis.”

“She’s coming, little brother.”

“Hurry her up. Please?”

“I can’t hurry her when she has such important work, brother.”

“I’m almost dead,” Jollo said. “I want to see her one last time . . .”

“Hush, Jollo. No more talk of death.”

“Easy to say when it’s not your life that’s . . . fading away.” His face became a tragic mask. “I want my mama.”

“She’ll come as soon as she can,” Covenantis said, only this time much more quietly, his voice filled with sorrow as though he knew, however fast she came it would never be fast enough.

“Don’t look up!” Mrs. Munn yelled over another round of shattering air. “Just be ready!”

“What do you mean?”

“You wanted the snake. Get ready to use it!”

Candy felt stupid and angry and confused all at once. She’d never imagined letting Boa go would escalate into such chaos: the Princess nearly killing Mrs. Munn, her firstborn, and Candy, and now breaking through Mrs. Munn’s defenses, still no doubt wearing the Sepulcaphs. The mere thought of them was enough to stir up nausea, so Candy concentrated on the snake.

Its body was too thick for her to get her hand around, but it didn’t seem to want to escape her grip. Quite the reverse. It slid the cool, dry length of its tail twice around one of her arms and then, raising up its large head so that it could look down imperiously at Candy it said, “I think myself a very fine snake. Do you not agree?”

Its speech, which was as elegant and smooth as its motion, came as no great surprise to Candy. It had been the greatest disappointment of growing up—far more wounding than finding out that there was neither an Oz nor a Santa Claus—to discover that though animals talked often and wisely in the stories she loved, few of them did so in life. It made perfect sense then that a creature she had fashioned in a moment of blind instinct would possess the power of speech.

“Are you the one who called me into being?” the serpent inquired.

“Yes, I’m the one.”

“Lovely work, if one may be so bold,” the snake said, admiring his gleaming coils. “I would have done nothing different. Not a scale. One finds oneself . . . perfect.” He looked a little embarrassed. “Oh dear, I think I’m in love,” he said, kissing his own coils.

“Aren’t you poisonous?” Candy said.

“Indeed. I can taste the bitterness of my own poison. One is of course immune to one’s own toxins, but if a single drop fell on your tongue—”

“Dead?”

“Guaranteed.”

“Quick?”

“Of course not! What’s a poison worth if it’s quick?”

“Painless?”

“No! What’s a—”

“Poison worth if it’s painless?”

“Precisely. My bite may be quite swift, but the consequence? I assure you, it’s the very worst. It feels like a fire is cooking your brains and your muscles are rotting on your bones.”

“Lordy Lou.”

Hearing the animal speak so lovingly of the agonies it could cause made Candy think of Christopher Carrion. Much like the snake’s poison, Carrion’s soup of nightmares had been lethal to others. But to Carrion, they’d been companions, trusted and loved. The similarity was too strong to be a coincidence. Candy had laced her invented snake with a little of Carrion’s essence.

The chat with the snake, along with Candy’s recollection of Carrion, had taken but a few seconds, during which time the sound of Boa battering on the last plate of air had grown steadily louder.

“Does your snake know what to do when Boa gets in?” Mrs. Munn yelled over the noise. “Because she’s a vehement one. She’s going to be through very soon, and you’d better be ready.”

“Oh, I think my snake knows his business,” Candy yelled back.

“Your snake, am I?”

“As long as you don’t object,” she said, doing her best to reproduce the snake’s imitation of high birth.

“Why would one mind?” the snake replied. “In truth, lady, one is both honored and moved.”

It raised its finely formed snout a little way, in order to deepen the bow that followed. Candy did her best to conceal her impatience (what part of her, conceiving of a snake, had created one with such humorless formality?) but it was difficult. The only thing that kept her from losing her composure was the serpent’s genuine commitment to her.

“You’ve won me over entirely,” it said to her. “I would kill the world for you, I swear I would.”

“Candy . . .” Mrs. Munn said. “Be quick or it’s ended.”

“I hear you,” Candy replied. “We’re ready.”

“Is it to be the world then?” the snake said.

“Thanks for the offer, but no, I just need you to stop one person.”

“And who’s that? The fat woman?”

“I heard that, snake!” Mrs. Munn yelled.

“No, snake,” Candy said. “Absolutely not. That’s our friend.”

“It’s not the world and it’s not the fat one. So who?”

“The one on the other side of the air,” Candy said.

“Why her?”

“Because she’s a bad piece of work,” Candy said. “Trust me. Her name’s Boa. Princess Boa.”

“Oh, now wait,” the serpent said. “This one’s royalty? No. No no. One has one’s limits. She’s one of my own!”

“Look at her! She’s no snake.”

“I don’t care to.”

“You were ready to kill the world for me just a minute ago!”

“The world, yes. Her? No.”

Mrs. Munn had not heard a single word of this. She’d been too busy using her strengths—mental, physical and magical—to keep the final plate of air, which was already badly cracked, from shattering completely.

It was a struggle she was going to lose very soon, Candy feared. Boa’s power was now so formidable that despite all the incantatrix’s years of wieldings, she had run out of energies to oppose her. In desperation she had reached into her very soul for strength. But even that had not been sufficient. Its fuel had been almost entirely burned through in seconds. When it was gone, her life would be over.

“I’m sorry, Candy . . .” The thundering of Boa’s forces beating against the final plate of air almost drowned her out. She drew a deep breath and tried again one last time. “I can’t hold her back. I’ve used everything I have. There’s no life left in me.”

“No! Mrs. Munn, you can’t die. Just get out of her way.”

“If I move, it’s over,” she said. “Boa will be through and we’ll both be vomiting.”

“You know what?” said Candy. “Let her come. I’m not afraid of her. I’ve got a killer snake right here at my side.”

“You don’t have me,” the snake said.

Candy had neither the time nor the temper left for debate. She raised the snake still coiled around her arm. “Now you listen to me, you pretentious self-loving, empty-headed worm—”

“Worm? Did you call me a worm?”

“Shut up. I’m shouting! You exist because I made you. And I can unmake you just as easily.” She had no idea whether this was actually true, but given that she’d brought the snake into being, it was a reasonable assumption.

“You wouldn’t dare!” the snake said.

“What?” Candy said, not even looking at him.

“Unmake me.”

Now she looked. “Really? Is that a request?”

“No. No!”

“Are you quite sure?”

“You’re crazy.”

“Oh, you’ve seen nothing yet.”

“And I don’t want to, thank you very much.”

“Well then, do as I say.”

She met the snake’s beady black gaze, and held it. And held it. And held it.

“All right!” it said finally, breaking his gaze. “You win! There’s no dealing with insanity.”

“Good choice.”

“I’ll bite her, but then you let me go.”

Before Candy could reply, Boa unleashed a shriek, which was drowned out seconds later, overwhelmed by the crash as the final plate of air shattered. The blast of energy slammed into Laguna Munn, who shielded Candy and the snake from the worst of its force. She, however, was picked up, despite her weight, and thrown like a straw doll, off into the darkness between the trees.

The snake’s instant response was to escape from Candy’s grip, the entire muscular length of its body writhing around in panic.

“So sorry. One has to leave. Look at the time.”

“Nice try, worm,” Candy said, reaching out and grabbing hold of its body, somewhere, she guessed, close to its head. She was loathe to open her eyes too wide to check on where she’d fallen in case an exploratory glance, however brief, gave her a lethal glimpse of Boa and her Sepulcaphs. On the other hand she wasn’t going to be able to use the snake against Boa unless she knew where the enemy was standing.

Suddenly the snake’s frenzied twists and turns stopped, and seizing the chance its sudden passivity offered, Candy slid her hand up along its body. She’d seen how real snake handlers worked. They seized hold of the animal right behind its head and held on with all their strength so that the snake couldn’t whip around and bite them.

But Candy’s snake showed no intention of doing so. It didn’t move at all. In fact, the reason for its sudden stillness was clear just a few inches farther along its body. A shoeless foot was pressed down upon the snake’s head.

“So . . .” Boa said. “I think it’s time you looked at me, don’t you? I can make you if I want to.”

Chapter 18

An EndGame

MALINGO WAS STILL STARING off between the trees, hoping to catch some sign of Candy’s return—so far no luck. What he did see was a flock of perhaps ten or twelve winged creatures, which looked through the trees in his general direction, barking and squealing, chattering and howling with the stolen voices of a dog, pig, monkey and hyena.

“What’s that noise?” Covenantis said.

“You need to see for yourself,” Malingo said, his vocabulary too impoverished to do the sight justice.

“I can’t look right now,” the slug-boy replied. “I’m . . . concentrating on something. It’s not something I can take my eyes off.”

“You need some help?”

“No,” the boy said. “This is for me to do and only me. Why don’t you just keep watching for Candy and Mama? And please . . . don’t watch me while I’m doing the wielding.”

“Are you going to do some magic?”

“I’m going to try. Just a verse and a chorus.”

“What?”

“They’re songs. Mama wrote down all the spells she learned or created as songs. They’re harder to steal that way, she says. I’ve been listening to Mama’s songs as recordings since I was about two. So I know all her magic because I could sing all her songs, every single one.”

“Did you understand them?”

“We’re about to find out, aren’t we? That’s why I don’t want anyone watching. If something goes wrong, at least you’ll have your back to it.”

“What are you going to do?”

“Nothing too ambitious. I’m a horrible singer. But I’d like to ease Jollo’s pain if I can.”

“Isn’t your mother going to go crazy when she finds out you’ve been stealing her magic?”

“Probably. But she’ll go even crazier if she gets back and finds Jollo’s dead. It’ll break her heart. And what kind of son will I be if I don’t try to stop my own mother’s heart from being broken? I’ll tell you. A bad one. I’ve disappointed her enough. This once I’m going to get it right.”

“Couldn’t you just wait a few more minutes?”

“Don’t ask me. Ask Jollo.”

Malingo glanced back at Jollo, and had his answer. If it hadn’t been for the very subtle rise and fall of Jollo’s chest, Malingo might easily have assumed the life had already left Jollo’s body.

“I have to start,” Covenantis said. “You keep looking for Mama or the Quackenbush girl.”

“They’ll come,” Malingo said, and turning his back to Covenantis he did as the boy had requested and stared off between the trees.

As he studied the corridor of shadow before him and ever-deeper shadow ahead of him he became aware that he, the studier, was himself being studied. He let his gaze follow his instinct up into the

lower branches of a tree close by. There sat three members of the pale-feathered flock that had made such noisy passage between the trees only a couple of minutes before. They were silent now, hushed perhaps by the melancholy scene below. He watched them watching him, unnerved by their scrutiny.

And then, from behind, came the sound of Covenantis’s voice, singing with unnerving accuracy, in a falsetto, a song his mother had obviously written to sing herself. It had the lilting rhythm of a lullaby. These were the primal sounds of an Abarat that was holding the Hours in trust for humankind to one day possess. Sounds that were about light and darkness, sky and sea, rock and fire.

“Kai tu penthni,

Kai tu ky,

Hastegethchem

Smannй fy.”

And death. That was the subject waiting behind all the other immensities. Death the merciless, death the irrevocable, the enemy of all things tender and easily broken: cracked like an egg dropped from a high place; burned black when lightning turned the forest to fire; killed by the cold, huddled in the cleft of a rock.

And still the ancient words came, flowing so fearlessly the boy might have been reciting his own name.

“U Tozzemanos,

Wo th’chem

Wo Kai numma

Jeth yo yem.”

What was he doing? Malingo’s curiosity grew more insistent the longer the recitations went on. What kind of comfort could he possibly be offering his brother that required the uttering of words so ancient and alien?

Malingo was in the process of instructing himself not to turn, not to look, when his body acted upon a demand far deeper than his instruction.

He turned and looked. Again his body overtook his mind, this time to simply expel a word—

“No!”

–not once but over and over and over—

“No! No! No! No!”

k

Candy didn’t waste time wondering why Malingo was shouting. She simply seized the moment, and with it, the snake. Boa’s foot was still on the animal’s head, but neither her full attention nor her weight were with it, so when Candy pulled on her invented beast it slid out from under the Princess’s foot without a struggle.

The serpent gave out a most unserpentine din of mutinous rage, writhing fiercely. She tried to grab its twisting coils with her free hand, but she was concentrating so hard on doing so that all thought of Boa and her lethal designs went out of her head. She half turned carelessly, and realized too late that her eyes had grazed the shape of Boa, moving toward her. Worse, they would not now let go. She tried to detach her sight from the form of the Princess—and worse, from the sight of the designs, moving up and over her face, forming their nauseating symbols in the air around her head. Signs to make a body recoil against itself: to make it turn itself inside out in a frenzy of disorder, to work against nature, against purpose, against life, and destroy itself.

So much destructive power was encoded in the patterns playing on Boa’s face. Even though Candy knew the harm they would make her do to herself, their enchantment had more power than her will. She couldn’t force it from her, even when she felt her stomach turning over—

“Don’t! Look!” Laguna Munn shrieked.

She didn’t have a gentle voice, a voice of calm or contemplation. No, her voice was rude and raw, which was just what the moment needed.

Much to Candy’s relief and astonishment, her eyes had obeyed the instruction. As soon as she looked away, her will was her own again.

“Good!” Mrs. Munn said. “Now quickly, girl! Give that damnable beast to me.”

Candy began to offer it, but Mrs. Munn was impatient.

“Give the beast to me!” she said. She appeared from within the trees and reached out to take hold of the animal. “Next time, call up an ax!” she said as she dragged the creature out of Candy’s arms. “Snakes are all teeth and talk!”

“I’ll make you regret—” the snake began to say, but Mrs. Munn was in no mood for its threats.

She wrenched its tail off Candy’s arm, and all but bundled the creature into a ball of black-and-yellow coils.

Then she told it: “Go bite a Boa!” and threw it at the Princess.

Grabbing hold of Candy’s sleeve, Mrs. Munn dragged her off between the trees, leaving Princess Boa and the conjured serpent to take out their lethal rage upon each other.

Chapter 19

The Price of Freedom

“A WALL OF BLUE FLAME Thorns is going around those two,” Mrs. Munn said as she hurried Candy away from the spot where they’d left Boa and the snake to match their venomous skills. The incantatrix was no longer the figure of calm power and confident abundance she’d been when Candy had first met her. The colors in her dress had been somehow removed, and one of her feather antennae had been torn out. Everywhere there was evidence of how hard the last few minutes had been. She was scratched, bruised, and sweating: an exhausted fighter still standing, but only by sheer force of will.

“When will the wall go up?” Candy asked her.

“It’s already up. No, girl, don’t look back! Lordy Lou, when are you going to learn some caution? You’re not playing games. The Boa girl may have been a civilized tenant when she was sharing your head, but that simply testifies to the power of your influence. You must have kept her villainy subdued, without knowing you were doing it. But she’s loose now.”

“What about the wall of Flame Thorns?”

“Oh, that’s not going to detain her for very long. Nor is that ridiculous snake of yours.”

“You were right. I should have made an ax—”

“It would have been no more use than . . . the . . . snake.” As Mrs. Munn’s words slowed down so did her pace until she was standing still, Candy beside her, staring off into the trees. Candy looked for some sign of Malingo, or of Jollo and Covenantis, but the shadows between the trees seemed particularly dense directly ahead of them: almost clotted.

“What’s wrong?” Candy said.

“One of the boys,” Mrs. Munn said. “Something’s happened to one of my boys.”

She started to pick up speed again, moving swiftly, parting the darkness ahead of her like a curtain with a few muttered words. Candy kept up, but there was no longer room for them to walk side by side: the trees and the shadows were too tightly packed. She could only follow after Mrs. Munn as she wove between the trees.

Finally, a figure appeared from the darkness ahead of them. It was Malingo. Even before Mrs. Munn had reached him, he began to apologize:

“I didn’t know how to stop him. He had these words . . . from one of your books—”

“Jollo was doing magic?”

“No, Mrs. Munn. It was Covenantis. He started reciting some sort of conjuration—” He put his hand up to his face, which was wet with tears. “I tried to stop him, but he took no notice. He wasn’t reading from a book so I couldn’t take the words away from him. He had them all in his head.”

“Oh, I’m sure,” Mrs. Munn said. “He’s a very intelligent child. That’s a piece of the good I put in him before he was born.” She studied the clogged darkness that lay ahead of them. “Where is he now?” she said.

“He’s still with Jollo. But I don’t know exactly where.” He frowned, and shook his head, confounded by his own stupidity. “They should be right there behind me, because almost as soon as I went off looking for you both—I couldn’t have taken more than two or three paces—I thought: this is wrong. I should do as Candy said and stay with them. So I turned back, and there was shadow, thick shadow, where there hadn’t been any before.”

“You know why.”

“Me?” Malingo said.

“You don’t have to say it,” Mrs. Munn replied, her voice softer than it had been until now. “Maybe you didn’t even realize you were running from it.”

“I wasn’t running from anything. I told you. I didn’t even know what was happening.”

Laguna Munn moved past Malingo, advancing toward a place from which all light had been driven. “But you heard it in the words he was saying.”

“It wasn’t a language I understood.”

“Even so, you heard it,” she said.

It wasn’t a question. She was merely stating what they both knew. He didn’t attempt to avoid admitting the truth any longer.

“Yes, I heard,” he said.

“Heard what?” Candy asked.

“Death,” he said.

And as if responding to that summoning word, the shadows ahead of the incantatrix tore themselves apart as though they were made of wet newspaper. Malingo didn’t want to see, at least not yet. He slipped between two trees, allowing Candy to follow Mrs. Munn, who had now passed beyond the shredded shadows, and was looking at what lay between the trees directly ahead of her.

The boy was dead, no doubt of that. His body had withered considerably more since Candy had last seen him, his flesh so drained of its vital juices that the bright, dark creature he had once been had gone entirely. What was left looked like a dwarf lying in a baggy shirt made of skin.

He looks so small, Candy thought: small and colorless. Jollo’s skin had been as black as the night sky, with fireworks streaking through it. Where had all that darkness and color gone? Death had scoured Jollo’s remains so completely clean that it looked more like his brother’s body.

Either that or—

Or what?

“I don’t think that’s Jollo, Mrs. Munn,” Candy said very quietly, as though the news might disturb the dead.

“I know,” Mrs. Munn replied.

The fact that the corpse was so very small now made sense. The remains before them weren’t those of the beloved and well-fed Jollo B’gog. It was Covenantis’s body, Candy realized, which lay in the grass.

“What happened to him?” Candy said, her voice hushed with horror. “Did the magic he was wielding backfire?”

“No. The wielding worked exactly as he wished it to,” Jollo said.

As he spoke he emerged from between the trees on the far side of his brother’s body. All trace of the damage Boa had done to him in consuming his life force had been healed, and Jollo was once again the gleaming, glorious creature he’d been when he’d first introduced himself to Candy and Malingo: his mother’s pride and joy. All he lacked was his dazzling grin.

“He used the Old Magic, Mama. I had nothing to do with it, I swear. He just gave me his life. I didn’t even know you could do something like that.”

“You can’t. Not easily. You have to find the right conjuration, and learn it perfectly, speak it perfectly. And then, of course, you have to be ready to give up your life.”

“That’s what he did, Mama. I didn’t even know he was doing it. I swear I didn’t.”

“So your brother gave up his life out of the goodness of his heart?”

“Not of his heart, Mama. Yours. That’s what you made him out of, isn’t it?”

Mrs. Munn stared hard at Jollo, clearly assessing his honesty. “And you, boy, I made from all the wickedness in me. My capacity for cruelty. And for vengefulness. And for lies.”

“Are you saying I’m a liar, Mama?” Jollo said. He literally bristled at the idea. His glossy black coat, which had lain so perfectly flat that Candy hadn’t even realized Jollo had fur until this moment, now stood up in three parallel ridges that went from the front of his head to the back, and described a spiral on his belly, centered where a normal child had a navel.

“Don’t you raise your hackles at me, boy!”

“Then don’t call me a liar when I’m not.”

“Your brother is dead, Jollo. I need to know why!”

“Then ask the geshrat!” Jollo said. “He saw it all!”

Mrs. Munn looked to Candy. “Where did your friend go?”

“He’s not gone far. I think he’s just keeping a respectful distance.”

She looked back over her shoulder, sensing Malingo there rather than seeing him, then quietly telling him:

“She’s not angry. She just wants to know—”

“Yes, I heard,” Malingo said, coming out of the shadows between the trees. “And it all happened pretty much as Jollo said it did. The little kid used a conjuring in Old Abaratian. I could feel the power in the words. And I saw the life, like a stream of light and water, running out of him and into Jollo, who was just lying there, near enough dead. He didn’t say anything to make it happen. It was Covenantis’s doing. The whole thing.”

“Did you try to stop it at least?” Mrs. Munn said.

“Of course. I started yelling at him. But that didn’t work. And he wouldn’t let me get close to him to stop him by separating them. When I tried, some force just threw me back, and I hit the ground. I kept trying but eventually there was no point. Covenantis just withered away. All he said was that he knew you’d understand. His exact words were: ‘Tell Mama: She’ll understand.’”

“Stupid,” Mrs. Munn murmured.

“I did what I could,” Malingo replied.

“Not you, geshrat. My boy. My firstborn.”

“It’s too late to say that now!” Jollo replied. “I mean, look at him! He’s gone forever, Mama, and he’s never coming back.”

Mrs. Munn nodded.

“If he wanted to punish me,” she said, “then he succeeded.”

“Punish you?” Candy said. “Why?”

“Because I was not the loving mother I should have been. Because I loved the darkness in me more than the light.” She approached the tiny body in its shroud of oversized skin, and went down onto her knees beside it. “Forgive me, child,” she said softly. There were tears in her voice.

“I think we should go,” Candy said.

“Yes, I think maybe you should,” Laguna Munn said, not turning to look at Candy or Malingo, just staring down at the dead boy.

“I’m . . . sorry,” Candy said.

“It wasn’t your fault. The error was mine. Be well, Candy Quackenbush. The struggles ahead of you will test you to the limits of your endurance. Beyond them, perhaps. But if you are in need of further healing . . .”

“Yes?”

“. . . don’t come here in search of it.” Tears thickened every one of her words. “Jollo,” she said. “Take them down to the harbor and find them a boat.”

“Thank you,” Candy said.

Mrs. Munn did not acknowledge her thanks, or say so much as a single word in reply. She had laid her hands on the body of her dead child, and her tears fell on it.

That was Candy’s last image of the great incantatrix, Laguna Munn: kneeling beside the body of the boy made from all the good in her, with her tears falling and falling.

Once out of his mother’s presence, Jollo became very talkative, keeping up a monologue of chatter about one subject only: himself. Was this a necessary part of evil? Candy wondered as she listened to him: this utter self-absorption, as though nothing else in the world mattered but Jollo and his boredom, Jollo and how he’d suffered during Boa’s attack, Jollo and what he was going to do when he left the rock and went out into the Abarat.