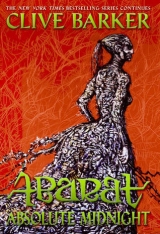

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

But each night it was the same story: exhaustion and disappointment. Just before dawn he’d come home to the dark, silent house, with his hands empty and his heart aching as it had never ached: not in sorrow, nor in regret, and certainly never out of love.

Tonight, however, there was a strange certainty in him that had him so eager to start his search that he had headed out into the night as soon as he heard Melissa switch off the lamp beside the bed where they had once slept as husband and wife.

In his haste to leave the house he had not only forgotten to make some coffee, but also to put on his windbreaker. No matter. One evil canceled out the other: the cold so bracing he could scarcely have been more awake, more alive. Though his fingers rapidly became numb, and his eyes ached in their sockets, the anticipation of joy and the joy of anticipation were so powerful that he pressed on without concern for his well-being, allowing his feet to choose streets to turn into that he would never have chosen, or perhaps even seen, before tonight.

Finally his wanderings brought him to a little cul-de-sac called Caleb Place. The waters of the Izabella had done extremely devastating work here. Trapped within the basin of the cul-de-sac, they had thrown their destructive power around the ring of houses, completely leveling several of them and leaving only three with any hope of being rebuilt. The most coherent of the surviving buildings was the one to which Bill Quackenbush was drawn. It was heavily cordoned off with wide plastic tape on which was repeatedly printed the warning:

DANGEROUS STRUCTURE DO NOT ENTER

Bill ignored the warning, of course. Ducking under the tape, he scrambled up over the rubble and into the interior of the house. The moon was bright enough to spill through the stripped roof to illuminate the interior with a silvery wash.

At the front door he paused for a long moment and listened. He could hear an unidentifiable sound from the interior: rhythmical, muffled. He listened carefully so as to at least locate its source. It was coming from somewhere upstairs, he concluded. He pushed open the front door, and waded through the litter of trashed furniture and bricks between the door and the stairs. The floodwaters had stripped virtually everything off the walls: the pictures, the wallpaper, even much of the plaster, which had fallen away in cobs making some of the stairs difficult to negotiate. But Bill had met and overcome many obstacles since Candy’s time in the Abarat. He wasn’t going to be dissuaded from this journey by a few littered stairs.

He experienced a few clammy moments as he gingerly stepped from one cracked timber to the next. But his luck held. He reached the landing, which was more solid than the stairs, without incident. He paused a moment to get his bearings, then he started down the passage toward the room at the far end, from which came, he was certain, the strange noise that had drawn him up here.

The room still had its door, which was open a few inches. He paused before it, almost reverentially, and then, using the pressure of just two fingers, he pushed. Creaking, the door swung open. The moon’s brightness illuminated half the room. The rest was in shadow. On the moonlit boards he saw scattered the source of the sounds he’d heard. Dozens of birds, common creatures he couldn’t have named even though he saw them on Followell Street whenever he’d gone out back. They were lying on the floor, as though some merciless force was pinning their heads to the boards, leaving them to flutter wildly, beating their wings so violently that the air was filled with flecks of feathers, which the constant updraft from the panicked wings below kept in circulation.

“What is this . . .” he muttered to himself.

In the dark half of the room, something moved. Something that Bill knew wasn’t a bird.

“Who’s there?” he said.

There was a second motion in the dark and something suddenly propelled itself out of the shadows into the wash of moonlight. It landed among the stricken birds no more than a yard or two from where Bill was standing, then leaped up again, so that with its second leap it struck the moonlit wall opposite the door. Bill got only a blurred impression.

It might have been a brightly colored monkey, except that he’d never seen a monkey move so fast. The motion drove the birds into a fresh frenzy, and some, in their terror, found the strength to escape their pinning. They rose into the middle of the room, apparently unwilling, despite the open roof above them, to depart the presence of whatever had attracted them here in the first place.

Their excited circling made it even harder for Bill to get a clear sense of the thing.

What was this strange entity pinned to the wall? It seemed to be made of fabric rather than skin: a patchwork of four, perhaps five, colored materials that ranged from livid scarlet to one of polished black with a dash of vibrant blue.

The beast didn’t appear to have any recognizable anatomy; there was no sign of anything resembling a head or even any of the features a head might have carried: it had no eyes that Bill could make out, nor ears, nor nose, nor mouth. Bill felt profoundly disappointed. Surely this couldn’t be the answer to the mystery of his nightly searches around town. The answer he’d been seeking had to be something more than some formless scraps of stained felt.

However, though there was little about the creature he found beguiling, he was still curious about it.

“What are you?” he asked, more to himself than anything.

The creature’s response, much to Bill’s surprise, was to stretch out its four extremities and draw all its power into itself. Then it kicked off from the wall and flew at Bill as though plucked by an unseen hand.

Bill was too slow, too surprised, to avoid it. The thing wrapped itself around him, blinding him completely. In the sudden darkness Bill’s sense of smell worked overtime. The beast stank! It had the stench of a heavy fur coat that had been put away soaking wet and had been left in a wardrobe to rot ever since.

The stench oppressed him, disgusted him. He grabbed hold of the thing and tried to pull it off his head.

“Finally,” the creature said, “William Quackenbush, you heard our call.”

“Get off me!”

“Only if you will listen to us.”

“Us?”

“Yes. You’re hearing five voices. There are five of us, William Quackenbush, here to serve you.”

“To . . . serve me?” Bill stopped fighting with the thing. “You mean, like, to obey me?”

“Yes!”

Bill grinned a spittle-grin. “Anything I say?”

“Yes!”

“Then stop smothering me, you damn fools!”

The five responded, instantly leaping off his head and back onto the wall again.

“What are you?”

“Well, why not? If he doesn’t like the truth because it sounds crazy, then he’s learned something hasn’t he?” the thing said to itself. Then it addressed Bill. “We were once five hats, belonging to members of the Noncian Magic Circle. But our owners were murdered and the murderer then celebrated his getting what he wanted by having a heart attack. So we were left looking for someone to give our powers to.”

“And you chose me.”

“Of course.”

“Why ‘of course’? Nobody has ever willingly chosen me for anything.”

“Why do you think, lord?”

Bill knew the answer without having to think.

“My daughter.”

“Yes,” said the thing. “She has great power. No doubt it comes from you.”

“From me? What does that mean?”

“It means you will possess greater influence than you ever dreamed of owning. Even in your wildest dreams of godhood.”

“I never dreamed of being God.”

“Then wake up, William Quackenbush! Wake up and know the reality!”

Though Bill was already awake, his instinctive self understood the deeper significance of what he was being told. The expression on his face opened like a door, and whatever was behind it caught the attention of the creature that had once been several hats.

“Look at you, Billy-boy!” it said, its five voices suddenly changed and harmonizing in admiration. “Such a radiance there is out of you! Such a strong, clear light to drive all the fear away.”

“Me?”

“Who else? Think Billy-boy. Think. Who can deliver us from the terror that your child is about to call down upon the world if not you who made her?”

At the moment when the creature had talked about Bill’s “radiance” the many silent birds Bill had seen rose into the air and circled around Bill in a vortex of bright black eyes and applauding wings.

“What are they doing?” Bill asked the shapeless thing.

“Paying homage to you.”

“Well, I don’t like it.”

“What do you want me to do?”

“Stop them.”

“Stop them dead?”

“Sure.”

“Sure,” the creature said, catching perfectly the tone of Bill’s response.

“Are you making fun of me?”

“Never,” came the reply.

A heartbeat later every single bird dropped out of the air and fell lifeless in the debris.

“Better?” the creature said.

Bill considered the silence.

“A whole lot,” he finally replied. He laughed lightly. It was a laugh he’d forgotten he was capable of: that of a man who had nothing to lose and nothing to fear.

He glanced at his watch.

“Almost dawn,” he said. “I’d better be going. What do I do with you?”

“Wear us. On your head. Like a turban.”

“Foreigners wear those.”

“You are a foreigner, Billy-boy. You don’t belong here. You’ll get used to wearing us. In our previous life we made very impressive hats. We’ve just come unglued of late.”

“I know exactly how you feel,” Bill said. “But that’s all going to change now, isn’t it?”

“Indeed it is,” said the remnants of Kaspar Wolfswinkel’s five hats. “You’ve found us. Everything changes now.”

Chapter 6

Under Jibarish

RUTHUS’S LITTLE BOAT CARRIED Candy and Malingo southwest down the Straits of Dusk and between the islands of Huffaker and Ninnyhammer to Jibarish, in the wilds of which a tribe of women called the Qwarv lived by preying on weary travelers, who they then cooked and ate. Rumor had it that Laguna Munn, the sorceress they had come to find, was sympathetic to the Qwarv, despite their appetites, tending to them when they were sick, and even accepting their offer to eat with them on occasion. Certainly the island was a fit place for such repugnant events to occur. It stood at Eleven O’clock at Night: just one hour from the horror of Midnight.

The islands were still, however, slivers of time sealed off from one another. Only sounds would find their way through for some reason, echoes of echoes, eerily remote. But it wasn’t difficult to identify the sounds from the nearby Hour of Gorgossium. There was demolition going on. Massive land-clearing engines were at work, bringing down walls, digging up foundations. The noise echoed off the heights of Jibarish’s west-facing cliffs.

“What are they doing over there?” Malingo wondered aloud.

“It’s best not to ask,” Ruthus said in a hushed tone. “Or even think about it.” He stared up at the stars, which were so bright over Jibarish that the sum of their light was greater than even the brightest moon. “Better to think of the beauty of light, yes, than to think of what’s going on in the darkness. Curiosity kills. I lost my brother Skafta—my twin brother—just because he asked too many questions.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” Candy said.

“Thank you, Candy. Now, where do you want me to let you off? On the big island or the little one?”

“I didn’t know there was a big one and a little one.”

“Oh yes. Of course. The Qwarv rule the big island. The little one is for ordinary folks. And the witch, of course.”

“By witch, you mean Laguna Munn?”

“Yes.”

“Then that’s the island we want.”

“You’re going to see the incantatrix?”

“Yes.”

“You do know she’s crazy?”

“Yes. We’ve heard people say that. But people say a lot of things that aren’t true.”

“About you, you mean?”

“I wasn’t—”

“They do, you know. They say all kinds of wacko things.”

“Like what?” Malingo said.

“It doesn’t matter,” Candy said. “I don’t need to hear silly things people dream up. They don’t know me.”

“And you as well, Malingi,” said Ruthus.

“Malingo,” said Malingo.

“They say terrible things about you too.”

“Now I have to know.”

“You’ve got a choice, geshrat. Either I tell you some ridiculous gossip I heard, and while I’m wasting my time doing that the current throws us up on those rocks, or I forget the nonsense and do the job you’re paying me for.”

“Get us to solid ground,” Malingo said, sounding disappointed.

“Happily,” Ruthus said, and turned his attention back to the wheel.

The waters around the boat were becoming frenzied.

“You know . . . I don’t want to be telling you your job,” Candy said, “but if you’re not careful the current’s going to carry us into that cave. You do see it, don’t you?”

“Yes, I see it,” Ruthus yelled over the roar and rage of the Izabella. “That’s where we’re going.”

“But the water’s—”

“Very rough.”

“Yes.”

“Frenzied.”

“Yes.”

“Then you’d better hold on tight, hadn’t you?”

Before another word could be exchanged, the boat entered the cave. The passage into the cave forced the foaming waters to climb and quicken, quicken and climb, until the top two feet of the boat’s mast were snapped off as it scraped the roof. For a few terrifying moments it seemed the entire boat and those aboard would be scraped to mush and splinters against the roof. But, as quickly as the waters had risen, they subsided again without any further damage done. The channel widened and the racing current eased.

Though they had already been borne a considerable distance into the body of the island, there was a plentiful supply of light, its source the colonies of phosphorescent creatures that encrusted the walls and stalactites that hung from the roof. They were an unlikely marriage of crab and bat, their bizarre anatomies decorated with elaborate symmetrical designs.

Directly ahead of them lay a small island, with a steep wall around it, and rising in a very sharp gradient, a single hillock covered with red-leaved trees (that apparently had no need of sunlight to prosper) and a maze of whitewashed buildings arrayed beneath the garish canopy.

“We’ll need rope to scale that wall,” Malingo said.

“Either that or we use that,” Candy said, pointing to a small door in the wall.

“Oh . . .” said Malingo.

Ruthus brought the boat around so that they could step out of the vessel and through the door.

“Give my love to Izarith,” Candy said to Ruthus. “And tell her I’ll see her again soon.”

Ruthus looked doubtful.

“Are you sure you want me to just leave you here?” he said.

“We don’t know how long we’ll be with Laguna Munn,” Candy said. “And I think things are getting chaotic. Everyone’s stirred up for some reason. So I really think you should go back and be with your family, Ruthus.”

“And you, geshrat?”

“Where she goes, I go,” Malingo replied.

Ruthus shook his head.

“Crazy, the both of you,” he remarked.

“Well, if things go badly for us, you have nothing to blame yourself for, Ruthus,” Candy said. “We’re doing this in spite of your good advice.” She paused, smiled. “And we will see you again.”

Malingo had already climbed out of the boat and was squatting on the narrow step, trying the door. It opened without any forcing.

“Thank you again,” Candy said to Ruthus, and stepped out of the boat, heading through the small and roughly painted door in pursuit of Malingo.

Before she stepped over the threshold, though, she glanced back down the bank. She had no chance to call good-bye to Ruthus. The possessive waters of the Izabella had already seized hold of the little boat and it was being carried away from the island, while the winged crabs applauded the boat’s escape with a mingled ovation of wing and claw.

Chapter 7

The sorrows of the Bad Son

A STEEP, NARROW– STEPPED PATH wound its way up from the door in the wall through the trees. Candy and Malingo climbed. Though there was a wash of visible brightness through the orange-red canopy, very little of it found its way down to the path. There were, however, small lamps set beside the steps to light the way. Beyond their throw the thicket was dense and the darkness denser still. But it wasn’t deserted.

“There’s plenty of eyes on us,” Candy said very quietly.

“But no noises. No birds chirping. No insects buzzing around.”

“Maybe there’s something else here. Something they’re scared of.”

“Well, if there is,” Malingo said, speaking with a fake clarity, “I hope it knows we’re here to cause trouble.”

His performance earned him a reply.

“You say you’re here to cause trouble, geshrat,” said a young voice, “but saying it doesn’t make it true.”

“Why are you here?” said a second voice.

“The sons,” Malingo murmured, the words barely audible to Candy, who was standing a single step away from him.

“Yes,” said the first voice. “We’re the sons.”

“And we’ll hear you,” taunted the second, “however quietly you whisper. So don’t waste your time.”

“Where are you?” Candy asked them, slowly climbing another step as she did so, and scanning the shadows off to their right, from which direction the voices had seemed to come.

In her hand she quickly conjured a little ball of cloud-light; a cold flame she had learned to call up from Boa. It had been, Candy vaguely thought, one of the earliest pieces of magic Candy had filched from Boa’s collection. Candy squeezed it tightly.

The moment would come when she had one of Laguna Munn’s boys close enough to—

There! A shadowy form moved across her field of vision. She didn’t hesitate. She raised her arm and let it go. It blazed yellow-white and blue, its illumination spilling only down at the figure Candy had willed it to illuminate. The cloud-light did its job and Candy saw the first of Laguna Munn’s boys. He looked like a little devil, Candy thought, with his stunted horns and his squat body made of shadow and shards of color, as though he’d stood in the way of an exploding stained-glass window, which hadn’t hurt him because his body was made of Dark Side of the Moon Jell-O.

When he spoke, as now he did, his voice was completely mismatched with his appearance. He had the precise, well-cultured voice of a boy who’d been to a fancy school.

“I’m Mama’s Bad Boy,” he said.

“Oh really? And what’s your name?”

He sighed, as though the question presented huge difficulties.

“What’s the problem?” Candy said. “I only asked your name.”

There was something in her plain, unpretentious Minnesotan soul that was not taking to Laguna Munn’s self-proclaimed Bad Boy.

“Oh, I don’t know . . .” he said, nibbling at his thumbnail. “It’s just hard to choose when you’ve got so many. Would you like to know how many names I have?”

She didn’t.

“All right, I’m listening. How many?”

“Seven hundred and nineteen,” he said rather proudly.

“Wow,” Candy said flatly. Then, even more flatly, “Why?”

“Because I can. Mama said I can have anything I like. So I have a lot of names. But you can call me . . . Thrashing Jam? No, no! Pieman Hambadikin? No! Jollo B’gog! Yes! Jollo B’gog it is!”

“All right. And I’m—”

“Candy Quackenbush of Chickencoop.”

“Chickentown.”

“Coop. Town. Whichever. And that’s your geshrat friend with you, Malingo. You saved him from being the slave of the wizard Kaspar Wolfswinkel.”

“You’ve certainly done your homework,” Candy said.

“Homework . . . homework . . .” Jollo B’gog said, puzzling over the word. “Oh. Work given to students by their tutors in your world, which they attempt to avoid doing by any possible means.” He grinned.

“That’s right,” Candy said. “On the nose!”

“On the nose!” Jollo B’gog said triumphantly. “I got it on the nose! I got it on the nose!”

“Somebody’s enjoying themselves,” said a woman, somewhere beyond the spill of the light that Candy had shed on Jollo.

The boy’s good humor instantly died away, not out of fear, Candy thought, but out of a peculiar reverence for the speaker.

“Bad Boy?” she said.

“Yes, Mama.”

“Will you find our guest Malingo something to eat and drink, please?”

“Of course, Mama.”

“And send the girl up to me.”

“As you wish, Mama.”

Candy wanted to point out that she was also hungry and thirsty, but this wasn’t the time to be saying it, she knew.

“All right, you heard Mama,” Jollo said to Candy. “She wants you to go to her, so all you need to do is follow the silver eye.” He pointed to a foot-wide eye, its pupil black, the lens of it silver, which hovered in between the trees.

“Should I come?” Malingo said to Candy.

“If I need you, I swear I’ll yell. Really loud.”

“Happy?” Jollo said to Malingo. “If Mama tries to eat her, she’s going to yell.”

“Your mother wouldn’t—”

“No she wouldn’t, geshrat,” Jollo replied. “It’s humor. A joke?”

“I know what a joke is,” Malingo said without much certainty. He looked for Candy, but she’d already followed the silver eye off the path into the darkness of the trees.

“Come on, geshrat. Let’s get you fed,” Jollo said. “If you hear Candy call, you can go straight to her. I won’t even try to stop you. I promise.”

Chapter 8

Laguna Munn

LAGUNA MUNN’S ISLAND HAD seemed small when viewed from Ruthus’s boat, but now that Candy was being led up through its darkened slopes it seemed far larger than she’d expected. She’d left the cloud-light behind her, but the silver eye shed its own light as it led her through the dense thicket. She was glad of its guidance. The ground beneath her feet was becoming steeper, and the trees she was moving between—sometimes having to force a gap large enough for her to get through—became steadily more gnarled and ancient.

There was a wind blowing up here on the higher elevations. It made the antiquated trees creak, and their branches shake down a dry rain of leaves and withered fruit. Candy didn’t let anything distract her from her guide. She followed it as closely as the passage through the choked undergrowth would allow, until it led her to a place where the trees’ lowest branches had woven their twigs with the bushes below, forming a wall of knitted wood. Candy stood before it a moment, while the eye cast its light upon the interwoven twigs. A few seconds went by and then a shimmer of motion passed through the wall, and where the eye had shone its light the wall unwove itself, opening a narrow door. The trees and shrubs were still parting when the voice that had spoken to Jollo said, “Either come in or be gone, girl. But don’t just stand there.”

“Thank you,” Candy said, and stepped between the writhing branches.

She had come to the top of the island. The wind here moved in sighing circles, the freight of leaves it bore rising and falling as it was swept around her. It wasn’t just leaves in the circling gusts, however. There were animals too, creatures of every size and shape moving around her, their flanks pale as the moon sometimes, sometimes red as a setting sun, their eyes blazing green and gold, and all leaving trails of motion on the shadowy air.

She couldn’t be sure whether she was witnessing a joyous race or a life-and-death pursuit. Whichever it was, it suddenly turned in her direction, and she dropped to the ground, hugging her head with her hands as she felt the rush of life passing over her. It was loud now. Not only the rush of wind but the thunder of hooves and paws, and the screeches, roars, and howls of perhaps a thousand species, perhaps twice that.

“Do you not yet know the difference between a dreamed thing and a living one?” Laguna Munn said, her voice closer to Candy than the sound of the animals’ passage.

“Dreamed . . . ?” Candy said.

“Yes, girl,” Laguna replied. “Dreamed. Imagined. Conjured. Invented.”

Candy dared a cautious glance up. Whatever the incantatrix was saying, the hooves and the claws that were still racing over the top of Candy’s head looked real and extremely dangerous.

“It’s an illusion,” Laguna Munn said. “Stand up. Go on. If you don’t trust me, how can anything I try to do for you have a hope of working?”

Candy saw the sense in this. She raised her head a little more. The violence of the living torrent galloped over the dome that protected her thoughts. It hurt. Not just her skull, creaking beneath the assault of the hooves, but the bones of her face, and the delicate tissues it protected.

If she didn’t endure this assault she’d not find anyone else to tell her what Laguna Munn could.

She stood up.

Lordy Lou, the pain of it! Even though it was an illusion it was still strong enough to make blood trickle from her nose. She wiped it away with the back of her hand, but a fresh flow immediately followed. And still the animals thundered on, the violence of their passage buffeting her as they pressed on.

“I know you’re there, Laguna Munn,” she said. “You can’t hide forever. Come on. Show yourself.”

Still the creatures came, their passage through her as powerful as ever. The blood running from her nose was in her mouth. She tasted it, copper and salt. How much longer could her body survive this relentless onslaught? Surely the incantatrix wouldn’t let her die because she failed?

“I’m not going to die,” she told herself.

Again, she tried to force her vision through the conjuration. Again the conjuration forced its reality upon her.

You’ll never do it without me, Boa said.

“Help me, then.”

Why should I?

A wave of anger rose up in Candy. She was sick of Boa; sick of every egocentric woman with more power than compassion that she’d encountered, starting with Miss Schwartz, and finishing up with Mater Motley. She’d had enough of them—all of them.

And finally, her eyes started to prick the illusion that was battering her, giving her a glimpse of the mysterious Laguna Munn. She was what Candy’s mother, Melissa, would have called a “big-boned woman,” by which she’d meant fat.

“I . . . see . . . you,” Candy said.

“Good,” Laguna Munn replied. “Then we can proceed.”

Laguna raised her hand, and made a fist of it. The tidal flow of living things ceased instantly, leaving Candy with aching bones, a buzzing head, and a bloody nose. Laguna spoke, her voice soft.

“I didn’t expect to meet you, though I was curious, I must say. I thought the Fantomaya had your affections.”

“The Fantomaya is the reason I’m here,” Candy said.

“Ah, so somebody’s been telling you stories.”

“It’s not just a story!” Candy snapped.

The anger was still in her, bubbling up.

“Calm yourself,” Laguna Munn said. She seemed to rise from her chair and move toward Candy without taking a single step. “What did I see in your head, girl?”

“Something more than me,” Candy said. “Another person.”

Laguna’s eyes, already huge, grew larger still, and brighter. “Do you know the name of this other in your head?”

“Yes. Her name’s Princess Boa. Her soul was taken from her body by the women of the Fantomaya—”

“Stupid, stupid . . .” Laguna Munn muttered to herself.

“Me?” Candy said.

“No, not you,” Laguna replied. “Them. Playing with things that they had no business with.”

“Well, they did it. And now I want to undo it.”

“Why not go to them?”

“Because they don’t know I know. If they’d wanted us to separate eventually, they would have told me she was there, wouldn’t they?”

“I suppose that’s reasonable, yes.”

“Besides, one of them has already been killed because I came over to the Abarat—”

“So if any other witch was going to die you’d prefer it to be me.”

“That’s not what I meant.”

“It’s how it sounded.”

“What is it about this place? Everybody playing stupid games! It makes me sick.” She wiped her bloodied nose again. “If you’re not going to help me, then I’ll just do it myself.”

Laguna Munn didn’t attempt to conceal her astonishment or the seam of admiration that ran beside it.

“Lordy Lou. You would, wouldn’t you?”

“If I have to. I can’t find out who I really am until she’s out of my head.”

“And what happens to her?”

“I don’t know. There’s a lot of things I don’t know. That’s why I came to you.”

“Tell me honestly, does the Princess want to have a life free of you?”

“Yes,” Candy said with confidence. Laguna stared at her with intimidating intensity. “The problem is that I don’t really know where I stop and she begins. I must have been born with her already in my head. And we’ve always lived together, her and me.”

“I should warn you, if she truly doesn’t want to leave, then you’ll have a fight on your hands. A fight like that could be fatal.”

“I’ll take the risk.”

“Do you understand what I’m—”

“Yes. It could kill me.”

“Yes. And I’m assuming that you’ve also considered the fact that there may be parts of you that aren’t you at all?”

“That are her? Yes. I’ve thought of that too. And I’d lose them. But if they were never mine in the first place—never me—then I’m not really losing anything, am I?”

Laguna Munn’s gilded gaze softened.

“What a crazy conversation there must be going on inside your head right now,” she said. “And I’m not talking about the one between you and your stowaway. It’s a pity you and I have met so late in life,” she said with what seemed to be genuine regret.

“I’ve only just turned sixteen,” Candy said.

“I know. And that’s young, I realize. But there are roads to revelation that should have been laid when you were just a baby, and laying them is going to be harder now. You came here in search of freedom and revelation, and I’m afraid all I can give you is warnings and confusion.”

“So you can’t separate me from Boa?”

“That? I can do that. I can’t make any predictions concerning the consequences of the separation. But I can promise you that you will never be the same again.”

Part Two

You, Or Not I

As thorn and flower upon a single branch sit,

So hate beside my love for her will fit.

Two pieces of one thing, that make a whole.

As you and I, my love, a single soul.

Chapter 9

A New Tyranny

IT WOULD HAVE COME as no surprise to the occupants of Gorgossium that the sounds of demolition were audible from the waters surrounding the island. Its inhabitants could barely hear themselves think.

The Midnight Island was undergoing great changes, all designed to deepen the darkness that held Gorgossium in thrall. It was not the darkness of a starless sky. It was something far more profound. This darkness was in the very substance of the island. In its dirt, in its rock and fog.

Over the years many had attempted to find the words to evoke the horrors of Gorgossium. All had failed. The abominations which that island had brought to birth, and nurtured, and sent out often across the islands to do bloody and cruel work defied even the most articulate of souls.