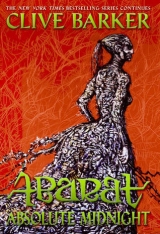

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“Please! Don’t—” Finnegan said.

“Don’t what? Gut her the way she was about to gut me? She fully intended to do it, you know. You were too weak. She wanted it done fast, didn’t she? ‘He’s dangerous.’ That’s what she said about me. Doesn’t that make you wonder? Why am I so dangerous?”

“Just let her go, Maas. I won’t hurt you—”

“Don’t you want to know her secrets, Finnegan?”

“Not from you I don’t. Just let her go.”

“You’re going to have to see for yourself, then.”

“See what?”

“Her little hideaway on Huffaker.”

“Huffaker? She doesn’t even like—”

“You can both go, courtesy of the powers of this place.” The ghost dragons continued to roil around, their images rising up on all sides. “I think the dead must want to forgive you. They look at you with pity, Finnegan, for what you have to suffer. I know you think the suffering is over now that she’s come back but you’re wrong. It’s just begun.”

“Let her go, Maas.”

“To Huffaker, both of you!”

Finnegan felt the air throb around him, and the forms of the ghosts became remote.

“Maas!” Finnegan yelled.

Then the cavern was gone, and he was standing out in the darkness of another island, another Hour. In that darkness there was only one source of light: it was coming from the crack of a door, a little way from where Finnegan stood.

Again, the air throbbed. And his Princess was suddenly beside him.

“The knife,” she said, looking down. “It was in my hand!”

“Boa. We’re on Huffaker. He said you used to come here.” He glanced back at her, but there was too much darkness for him to see her. “Is that true?”

Boa looked and realized Finnegan was right. She sighed.

“Yes, love. It’s true. And I suppose you had to see sooner or later, didn’t you? Come. Let me show you my secrets.”

They walked together through the darkness to the threshold of the door, where the light fell. There was no sound around them. Nothing moved. Nothing sang. It was just the two of them as they approached the door.

“Touch nothing,” she said, and led the way inside.

Chapter 42

The Fiends

IN THE MAP-MOSAICKED ROOM at the top of the Needle Tower, Mater Motley surveyed her creation, and was satisfied. The Midnight Empire she had planned for, labored for, lived for, now owned the Abarat from horizon to horizon, with the exception of the Twenty-Fifth Hour; though it was only a matter of time, she was sure, until that most perverse of Hours fell to her. Everywhere Mater Motley sent her remote gaze, it was the same triumphantly desolate story. Where there had been calm there was now chaos and violence. Where there had been celebration there was panic and terror.

On several islands she observed desperate attempts being made to provide some light to cure this darkness. Many, much to her satisfaction, ended in disaster.

On Hobarookus, for instance, she witnessed the tribal wizard of the Amurruz attempt to propel himself, accompanied by a number of warriors, into the smothering darkness overhead with the apparent intention of hacking a hole through to the stars. But the sacbrood were formidably violent, despite the fact that they were imprisoned in a jigsaw of their own interlocked bodies and their solidified excretions. After a brief, noisy encounter, a rain of body parts fell upon the upturned faces of the Amurruz, marking the brutal end of that foolish act of bravery.

On the Isle of the Black Egg, the Chief of the Jalapemoto nation ordered the igniting of a pool of highly combustible kaizaph oil—which offered a comforting source of warmth and light for several hours, until the fuel in the shallow pool had been entirely consumed. Then the hungry flames followed the path of the oil into the seam that fed the pool, which divided and divided as it spread out across the plateau. Within half an hour cracks began to appear in the ground, followed quickly by sinkholes, gouting flame, which claimed the lives of thousands of Jalapemotian inhabitants.

And while these exquisite follies played out, the fiends came out of hiding. Mater Motley couldn’t possibly have witnessed all of their reappearances, but she saw plenty. Creatures of every kind—bestial, grotesque, crazed and infernal—they all came out of hiding. Some she knew by name from her grimoires: monstrous descendants of the Eight Evils who had first walked the Abaratian stage. The devourers of ruins called the Waikami; the phantom, Lord Hoath; the many-tongued beast, Morrowain; the death’s head creature know as the Depotic; the raging, gape-mouthed monster simply called the Overlord.

And for every one beast she could name there were twenty she could not: abominations that had passed the ages hiding in the intricate systems of caves and passageways that lay beneath the Hours, or in barrows and pits where they had been buried permanently by those who had fought them and believed them dead. Many had lived out the ages in solitude and darkness, nurturing their rage, emerging only when hunger drove them to risk being exposed and hunted down; others had procreated over the centuries, and emerged from their sanctuaries with immense families, their grotesqueries multiplying over the generations. A few had lived well: worshipped in secret temples by Abaratians who considered them to be the raw stuff from which divinities were made. These fiends, made arrogant by years of worship, rose with their legions of believers all around them: ordinary men and women of the islands who had secretly been paying homage to these bleak-hearted deities over the years.

Almost everywhere Mater Motley’s roving eye traveled it fell upon sights that would have sickened and appalled a compassionate spirit, but that filled her with a venomous joy. It wasn’t only for herself that she felt this joy. There were other eyes watching how her plan to unknit the order of the Abarat proceeded: the eyes of beings ancient and insatiable, whose presence she had only glimpsed as a monumental, limitless shadow thrown across or beyond what was neither space nor substance, presence nor absence. At some time not far from now they would show themselves, she knew. They would descend out of their mystery and be seen, here in the Abarat. And on that day she would be elevated to the highest throne for the services she had done them.

Meanwhile, she had another order of business to observe: the arrests. Her stitchling legions had already reached many of the islands. Already Mater Motley had seen the arrests of hundreds of individuals who would have caused, had they not been arrested, conflict and rebellion in the future. She’d seen the possibility in the visions the Powers That Be had allowed her to witness, and it was a future she had vowed to keep from coming into being. On the dark side of Scoriae she had, many weeks ago, ordered a camp to be built where all these agitators and troublemakers would be kept. It was a rudimentary place. The huts that had been hastily built to have the arrestees stripped of their personal belongings—jewelry, wallets, expensive shoes—and their presence recorded did not keep out the cold wind that incessantly blew so close to the Edge of the World. The camp had very little healthy drinking water, and the supplies the inmates had been given to make soup with were laughably inadequate, but Mater Motley saw no purpose in giving comfort and nourishment to people she was going to have executed within hours.

Meanwhile, the number of arrests continued to grow. Every outsider, every radical, every dealer in visions and hope—in short, anyone who had ever stood against her in word or deed, or that she suspected of one day doing so—was taken from their homes and family without explanation, and interned in the camp at Scoriae.

The Old Mother was well pleased.

Chapter 43

Dark Waters

THE TASK OF RESCUING the survivors from the turbulent waters around The Great Head had quickly degenerated into chaos, as people struggling in the water converged on The Piper from all directions and attempted to clamber aboard. Within two or three minutes of arriving at the scene The Piper was carrying more than its limit of passengers, and listing badly to starboard.

“We have to get out of here, Candy!” Eddie said. “We’re over the limit for passengers, Candy. They’re going to sink us! Are you listening to me?”

Candy stood frozen in place.

“Okay, fine. Then I’ll just go tell some drowned people we’ll be joining them soon.”

Candy continued staring off into the starless, moonless, cloudless sky, her body convulsed by little spasms.

“Malingo?” Eddie hollered. “I think there’s something wrong with Candy. She’s having a vision or a fit or something! Get over here, will you?” As he yelled he shoved his diminutive foot into the middle of the same brutish face of a man he’d shoved back into the water just a few moments before. “Can’t you take a hint, mate?” he bawled, “There! Is! No! More! Room!” He put all the strength in his body into making sure that this time the man stayed down. “Who’s at the wheel?”

“We are!” came a chorus of Johns from the wheelhouse.

“We have to get out of here!” Eddie yelled.

“He’s right!” Gazza shouted. “Much more of this and we’re going to be flipped over.”

“Just get this crawfiddlin’ thing moving,” Eddie said.

“There’s people in the water right in front of us,” Mischief said.

“They’ll get out of the way when they see us coming!” Eddie yelled back.

“We can’t just—”

“Gazza! Get to the wheelhouse and take over from that gaggle of idiot heads that some gene-deficient woman had the misfortune to carry to the tragedy of birth.”

“You are despicable, you know that?” John Mischief said. “Nobody put you in charge here. You’re just an actor.”

“Oh no, that was just a role I was playing!” Eddie said. “I’m a man of action. I get things done. You and your brothers just talk, talk, talk. All the time. Talk, talk, talk.”

The John Brothers said nothing. Except Serpent, of course, who couldn’t help himself.

“Your time will come,” he murmured to Eddie.

“Well?” Eddie yelled.

“I’m in the wheelhouse,” Gazza hollered. “They gave up the wheel.”

“Good,” Eddie said. “Now get us out of this mess.”

“I’m working on it.”

“How’s Candy doing?” Eddie asked Malingo.

It wasn’t Malingo who replied. It was Candy.

“Lordy Lou. She’s still with me!”

“Who?” said Malingo.

“Boa. Who else?”

“She’s here with you now? In your head?”

“No. But we’re still connected somehow. She just pulled me into her head. I don’t even think she meant to. I saw through her eyes for a moment. She was in some place filled with bones. Then—I don’t know how—we moved on.”

“Who’s we?”

“She has Finnegan,” Candy said. She put her hand up to her head. “I saw him right beside me. No, not me, her. Beside her. I’m all backward.”

“You said they moved on?”

“Yes.”

“Where to?”

“I don’t know.”

“Hazard a guess?”

Candy closed her eyes.

“Carrion built her a place to play . . .”

“Play?”

“Magic games. Oh—it’s Huffaker!”

“And you think that’s where she took Finnegan?”

Before Candy could reply The Piper’s engines made a guttural growl, and the boat surged forward perhaps twice its length before the engine made a second sound, far less healthy than the first, and the vessel shuddered to a halt.

“No!” Eddie yelled. “No! No! NO! This is not the place to lose power, Gazza! Get this hog-boned boat moving.”

“Then stop cursing at us,” said John Mischief. “And make yourself useful. There’s nothing wrong at the helm. And the engine’s still going. Something’s jamming the propeller. Gazza, can you find out what it is?”

Gazza gave a quick “Aye, aye, Captain,” and raced toward the propeller. Peering into the water he said, “It’s just some piece of trash wrapped around the propeller. I’ll cut it away and—”

The boat lurched. First to port, then to starboard, then to port again, this time so deeply it took on water. All the desperate creatures they’d tried to leave behind had swum in pursuit of them, and they, plus a hundred others, had grabbed hold of The Piper.

This time there would be no saving the ship. This time she was going down, taking everyone aboard with her to feed the fishes.

Chapter 44

Pariah

THE PIPER HAD PLAYED its last tune. Its boards creaked and cracked as one desperate soul after another sought to save themselves from the seething, bloody waters of the Izabella. They were already littered with the bodies of those who had died in the collapse of The Great Head or had fallen prey to the countless beasts that had risen from the depths with the Requiax. Terror had made them mindless and merciless, clawing at one another as they attempted to clamber up onto the boat, even though it was lurching wildly.

“This is the end,” Malingo said. “Candy, I’m sorry. It shouldn’t have ended like this. What am I saying? It should never have ended. I thought we would go on forever, I really did.”

“It’s not over yet!” Gazza said. “Look up! Look up!”

Everyone did as Gazza instructed. Nine or ten winged constructions that looked like the skeletons of vast birds, were circling high above The Piper. Their broad skulls were crowned with elaborately woven ziggurats of blazing bone, their wings, fully twenty feet wide, gilded by firelight.

And in the many ribbed bodies of these extraordinary mechanisms, lying flat along their midsections, were their pilots. One of which was Geneva.

“Candy! Be ready!”

“Geneva?”

“Of course!”

“It is!”

Candy could scarcely believe what she was seeing, but there she was, Geneva Peachtree, lying in the long cage of the bone-glider’s body.

“I couldn’t leave you to die!” Geneva yelled. “But I needed help!”

“You’d better be quick!” Gazza hollered. “We’re going down fast.”

“Geneva, be careful,” Candy shouted. “Don’t get pulled down! These people—”

“Smallest first!” Geneva ordered. “Malingo, pick up Eddie!”

“Now?”

“Now!”

What happened next was so fast and so extraordinary Candy could scarcely believe it was happening. Two of the fliers swooped down toward The Piper, as Malingo lifted a protesting Eddie up—

“Put me down!”

–first onto his shoulders, and then—

“I don’t need help, geshrat!”

That was all he had time to say. The fliers were carrying between them a hammock, which scooped Eddie up like a fish in a net, lifting him into the air. Their burden was nowhere near heavy enough to prevent them from rising again with their catch.

“You’re next, Candy,” Geneva yelled.

“No, it has to be Gazza! I won’t go until he goes.”

Geneva knew she had no time to argue with the girl, so she didn’t even try.

“Gazza it is!” she said.

“Wait!” Gazza protested. “Don’t I get to have—”

“An opinion?” Geneva yelled.

“Yes!”

“No! You’ve only got one chance at this!”

Two more fliers swooped down, needing to drop lower this time, not only because Gazza wasn’t raised up on Malingo’s shoulders but because in the half minute since Eddie’s rescue, The Piper had sunk significantly lower in the water.

“Now you!” Malingo said to Candy.

“No, I won’t—”

“We heard that already,” John Serpent snapped. “Don’t be selfish, Candy.”

“What?”

For the first time, Candy found all the brothers staring at her. “If we drown, it’ll be a pity. If you go it’s a tragedy. And you know it. We’ll get Malingo, don’t worry.”

In that instant some combustible substance in the rubble of The Great Head erupted in garish flame, and its light illuminated John Serpent’s face.

“Go,” he said.

She nodded.

“I’m ready!” she yelled to Geneva. The words were barely out of her lips when the third pair of fliers swooped down and she was lifted up, and up, and up, into the safety of the sky, where the bone-gliders wheeled.

Some time later, every soul aboard The Piper was safely deposited back onto the lantern-lit northeastern shore of Ninnyhammer, where Candy found she had a host of reunions awaiting. The first Abaratian to have ever shown her hospitality, Izarith, along with her two children, was there. So was the munkee called Filth she’d met in the Twilight Palace, and the members of the Totemix. It was no accident that all the people she’d encountered along the way to this place and moment were here.

“We watched you from the first step you took into the Abarat,” Geneva explained to her.

“When you say we, you mean—”

“All of us. The Kalifee.”

“It’s more than just us, though,” said Izarith.

“Not many more,” Geneva said quietly.

“Sad but true,” one of the Totemix said. “We’ve known this Midnight was coming sooner or later. We’ve read the omens.”

“So we started assembling a force—”

“The best of the best,” Filth said, his fingers plunged deep into one of his nostrils.

“Appearances can be deceptive,” Geneva remarked, catching the look on Candy’s face as she watched Filth snot mining.

“Kalifee means troublemakers. Rebels,” Izarith explained. “But we haven’t managed to do much to defy Mater Motley. She’s clever—”

“Or we’re too stupid,” said Filth. “Maybe a bit of both.”

There were more familiar faces appearing, stepping out of the shadows into the lantern light: Jimothi, head of the tarrie-cats, and some faces she remembered from the crowded boardwalks of Babilonium.

“Why was the Mazathatt watching me?” Candy asked Geneva.

“We thought you were working for her. The Hag.”

“Why?”

“You came from nowhere. But you had power,” Izarith said. “It was no accident that I invited you into the house, I’m afraid. That was me chancing to take a long look at you.”

“And?”

“We knew immediately you weren’t working for her. Evil stinks; you didn’t.”

“Thanks.”

“But we still had questions,” Geneva said. “We’d put together some pieces of the puzzle. We knew the Fantomaya had been tinkering with your mind before you were even born.”

“Doing what?” Candy said.

“Nothing that we didn’t think necessary,” said Mespa, who now also stepped out of the shadows with Joephi at her side. “We needed to keep you hidden from your lodger, and she from you. But it was a hastily conceived plan, and the magic was less than perfect.”

“We were arrogant,” Joephi said bitterly. “We thought our sisterhood was beyond error. Huh.” She shook her head. “It shames me still.”

“What do you mean: error?”

“It was poor thinking. Arrogance will do that.”

“We thought we had your life under control,” Joephi said. “But—”

“I changed,” Candy replied.

“Yes. Oh yes. You certainly did. Watching you deciding to go back to that little boat at the Yebba Dim Day even though you knew it was almost certain death to do so. Oh yes. We were in error.”

“Hence this moment with the good souls who fought the Hag in secret ways for years, and won little for their efforts.”

“And died,” Geneva said softly. “In ways only an abomination like the Hag could have conceived.”

“She was the reason we had such doubts about magic. We had come to think that it corrupted everything it touched. Look what it did to your people, Candy.”

“My people?”

“’Manity.”

“Is that what you call us?”

“It’s one of the politer terms.”

There was a subtle undercurrent of laughter.

“And what magic did you do to us?”

“Gave you power you lacked the skill to control.”

“Oh, that. Yes, I’ve seen some of that.”

“You mean your father’s cruelties?”

“Yes.”

“If you can find it in your heart to pity him . . .”

Candy thought about this for a moment. “No,” she said. “I can’t.”

“Well, that’s honest.”

“Was he always a man of vision?”

“My dad? Vision? Ha! You must be kidding. He likes beer, girlie magazines, kid’s cartoons, beer, being mean, and beer. He believes in nothing.”

“Well, he seems to have founded a religion.”

“You call that a religion? What was it called? The Church of Cold Pizza?” Her audience looked at her blankly. “Never mind. ’Manity joke.”

“We call it the Church of the Utter Void,” Geneva said. There was laughter now. “Abaratian joke.”

“Well, I don’t worship there,” Gazza said.

“There’s a time for everyone . . .” Geneva said flatly.

“Are you preaching for the Church of the Utter Void now?” Eddie said.

“No. But it has its attractions, doesn’t it? To have no more dreams you have to protect. To have nothing you love so much you live in fear of losing it. That wouldn’t be so bad . . .”

“It would be death,” said Candy.

“And would that really be so terrible?”

“Yes,” Candy said. “Of course it would. I didn’t just escape dying to go and give it all up because some preacher says it’s better that way. We still remember the light. We still remember happiness. Well, don’t we?”

“You make it sound very simple,” Geneva said.

“Well, to me it is. I want the Abarat to survive all this darkness, and come back stronger than ever. But I need to tell you something that might be important.”

“And what’s that?” said Mespa.

“On The Piper I realized that I still had a connection to Princess Boa. I could see through her eyes.”

“Oh, Lordy Lou!” John Mischief said. “Does that mean she can see through yours? Is she looking at us right now—”

“I don’t think so.”

“If she is, then she’ll know where we are!” Eddie said.

“Eddie, calm down.”

“Why didn’t you say something before now?”

“Because the feeling came and went. I think maybe it was just there for a few seconds. Perhaps because I thought I was going to die. I don’t know.”

“Even if this feeling has passed,” Geneva said, “Eddie’s right. You should have said something the moment you had a chance! You shouldn’t even be looking at me. Don’t look at anybody! I can’t believe you would be so stupid as to endanger our entire enterprise!”

“All right, all right!” Candy said.

She turned her back on them all, and stared up at the empty sky.

“There’s no need to treat me like a total leper,” she said more quietly. “I told you, Boa only came through for a few seconds. I don’t know why. Whatever the reason was, I can’t feel her presence any longer.”

“Which proves absolutely nothing,” Geneva said. “You know how sly she is. She could be behind your eyes right now and you wouldn’t even know it.”

“Well, she isn’t.”

“Candy. Think about it. How would you know whether she was or she wasn’t?”

“Because I’m not the ignorant girl I was when I lived in Chickentown. Because I threw her out of me, and just because there’s one little strand of her left in there doesn’t mean she still owns me. But I understand. She’s planted a little seed of doubt in you, and now I’m stuck with it.” She raised her arms in mock surrender. “I’m going to not look at any of you. I’m just going to walk down to the sea and think. And if she is looking out of my eyes all she’s going to see is blackness. Happy?”

And so saying she walked down to the water and looked out at the darkness, wondering as she did so as if the darkness was looking back at her.

Part Five

Stormwalker

A Man will always

Rise to the bait of

His higher self, however

Turbulent the waters it is

Cast upon.

Chapter 45

The Business of Empire

WITH THE MANY HUNDREDS of seamstresses Mater Motley trusted and considered most experienced out among the islands leading the Death Squads, their task of gathering up any troublesome individuals who might be using the chaos to work on chipping away at the foundations of her Empire, Mater Motley’s messenger of choice had become Maratien.

Twenty-two hours had now passed since the sacbrood had been released. In that time, Maratien had come to know the interior of the tower very well as she carried messages up and down its stairways. She had brought letters of supplication or surrender from those in power from across the Hours, all of whom had lately come to understand that they would forfeit both their territories and their lives if they did not pay their respects to the woman they’d once called the Mad Hag of Gorgossium.

Mater Motley made Maratien read the begging, self-serving missives aloud, but the Old Mother seldom had patience enough to hear more than a paragraph.

“Enough,” she’d say.

And Maratien would do precisely as her mistress instructed, letting go of the offending plea near one of the windows where a gust of wind could carry it away. There were a few occasions when Motley confiscated a letter herself. These were all from sorcerers and wizards who claimed to have had some romantic liaison with the Old Mother. They were treated with particular contempt, snatched from Maratien’s fingers and torn to shreds before the wind took them.

In the end, no claim—regal, religious, or sentimental—carried any weight.

There were only three letters that the Old Mother paid any attention to. The first was from one of the Old Mother’s loyal seamstresses, who wrote to inform her that she had heard rumors that somebody who closely resembled Mater Motley’s missing grandson, Christopher Carrion, had been seen on three islands: the Black Egg, Huffaker, and Ninnyhammer.

“I have heard, Lady Mother, that you believe your grandson may have left this world for that other at our soles. If you have proof that this is the case, then my information will be of little interest to you. But I offer it nevertheless . . .”

This letter Mater Motley kept for herself, making no comment upon its contents. She did the same with a letter from another of those seamstresses, whom she counted among her inner circle, who wrote to tell her she was optimistic that she would soon be able to report the arrest of the rebel, Candy Quackenbush, and asking whether, when that happened, was the girl to be brought to Gorgossium or taken to join the condemned souls in the camp on Scoriae? To this Mater Motley dictated a reply, which Maratien dispatched.

Mater Motley was of the opinion that when the criminal Candy Quackenbush was in custody, the girl was to be taken to Scoriae, treated like the common criminal she was, and executed as such.

The third letter, which the Old Mother studied very closely, was from the Captain of a squad of warrior stitchlings called skulliers. He was departing from the streets of Commexo City, where the skulliers, every one of them sewn up with war in its threads, were driving Commexo’s forces to a harrowing defeat. But, the Captain reported, the architect of Commexo City then threw on to the battlefield a force she had not known existed.

“He has legions of likenesses of that infernal child of his, the Commexo Kid. All of them are a perfect copy of the original (if indeed there ever was a living original, which I highly doubt). These legions came against us in swarms, with no weapons except their numbers, which I begin to fear are limitless. Knowing the importance with which you view the extinguishing of the city’s lights, I am writing in the hope that you may somehow lend your own powers to those of your faithful legions. I fear the victory that is your right will not come to pass until the balance of power is tipped in our favor, and I can think of no more certain way of making that a reality than by your personal intervention to turn the tide of this battle. I believe with your presence here the struggle to extinguish this city and to hang the architect, Rojo Pixler, from a lamppost, will be quickly realized.”

The letter moved the Old Mother to action on the instant. She wrote some fifty letters on the air, and conjuring for each a wind to bear it away, let them go their many ways. Then, ordering Maratien to accompany her, she called down the ethereal staircase that led from the mosaic-laden chamber up to the roof of the Needle Tower.

“Stay close to me, girl,” the Old Mother said. “I am about to let powers loose in whose path I would not want you to get caught.”

“They would harm me?”

“They would kill you, Maratien. Take the hem of my dress. Why do you hesitate?”

“The dolls, lady.”

“Souls. That’s all they are. Enemies of our mighty intent. They’re just afraid that you’re going to take them from me. Go, grip the gown tight. Tighter still. That’s it. Now don’t move.”

“I won’t.”

“Good. Trust me. You’re quite safe. Take the visions as they come.”

“I am ready, my lady.”

“You must be brave and drink in all the visions I am about to show us. They will exist but once. After my Midnight, they will be gone. For there has never been such a sight as this before, nor will ever be again.”

So saying she pulled the collar of her gown away from her neck, exposing her clavicle. There was precious little flesh upon her, and the finely curved bone stood clear of her skin, which had a jaundiced hue. With a sudden burst of speed, she reached into her own flesh and caught hold of the bone, snatching it out of her body, apparently without any pain. A metallic tang attended its revelation, a smell of magic, which drew countless blends of darkness out of air.

“What’s happening?” Maratien asked, her voice shaking, more with awe than with fear.

“I am calling together the nine parts of my beloved deathing ship, The Stormwalker, which was the labor of a hundred years and ten to build, all of it done in hiding.”

“Why so long?”

“That will be plain, when you have sight of it,” Mater Motley said. “Be patient, child. The pieces rise, even as we speak.”

She spoke the truth. As soon as she had raised her summoning clavicle into the air, and her orders had gone forth, in nine places around the islands, all of them wastelands or wildernesses where nothing lived to know the secret that lay hidden in the earth there. Now the buried mysteries rolled over in their tombs of dirt and stone so that the ground cracked and gaped. Nine vast implacable forms, none smaller than a cathedral (and most much larger), slowly rose up into the air.

Two of the nine parts of The Stormwalker moved toward each other as they had been programmed to do before they were buried, their massive forms tumbling over as they converged, meticulously aligning themselves so as to fit perfectly with the other, the two becoming one. The new singularity formed the vast engine of the machine, the thunder of which rolled around the sky. There would be lightning to accompany it in time, spat from the underbelly of what would be, upon completion, a vessel three-quarters of a mile long—the Stormwalker Christopher Carrion had spoken of—so called because it would stride on legs of lightning.

Mater Motley called forth visions of the remaining seven parts resurrecting themselves, throwing off their blankets of earth and rising to greet the first morning of the Night. She felt the profoundest pleasure to witness the approach of the nine parts of The Stormwalker. Only she knew the genius that had brought the vessel into being. Only she knew that the forges in which its many metals had been melted together, in an alloy so black it made Midnight look like a blaze of Noon, had not been fired up in the Abarat, nor ever could have been. Only she knew that the minds that had aided her in its design and construction had been those of beings more remote from the islands than the stars. They were the Nephauree. They were from a place, or state of mind, called the Zael Maz’yre. It, and they, existed behind the stars.