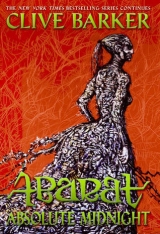

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

There was a moment of silence between them, and then Candy’s eyes drifted back over the edge of the boat. The lone squid she’d seen before had found a companion.

“Oh no!” she said, with sudden urgency. “Finnegan!”

“What about him?”

“Boa’s going to go to him the moment she gets away from Jibarish. And he’ll be so happy he’ll believe whatever story she tells him.”

“Perhaps some of it’ll be true.”

“Like what?”

“Well . . . maybe she still loves him.”

“Her? Love? No.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“Because I know what she is inside. I went and spied on her, in her dreams. And there’s only room for one person in Boa’s heart.”

“And that’s Boa?”

Candy nodded.

“Do you think she’d hurt him?”

“I think she’s capable of anything.”

“Then we should find him.”

“Agreed,” Candy said.

“I suppose I row now,” Malingo said unenthusiastically.

“We’ll each do some,” Candy said.

“So . . . we’ll head for Qualm Hah, yes? That’s where the John Brothers said they’d be. We’ll find them with the help of a little magic, and then catch another ferry to the Nonce.”

“Right now I think I’ve had enough playing with magic.”

“Understood,” Malingo said. “We’ll just find them the old-

fashioned way. And we can talk about whether you’re going or staying later . . .”

“I’m not going to change my mind, Malingo.”

He gave her a sly, sideways smile.

“Later,” he reiterated.

Chapter 23

Cold Life

ON THE WESTERN EDGE of the Isle of the Black Egg, where the Pius Mountains formed a grim wall between the Izabella and the island’s interior, was a stretch of coastline known as the Shore of the Departed. It had earned the name from a grim, grotesque phenomenon. Owing to some peculiarity in the way the submerged coastline was configured, whatever litter the waters of the Izabella had gathered as they moved along this part of the island was here shunned and pitched up onto the shore by a current too languid to carry it any farther.

Thus, borne up and deposited on the Shore of the Departed, were the remains of humble fishing skiffs and massive ironclad war vessels, foundered upon the reefs of the Outer Islands, many of which remained uncharted. Sometimes there was little more than a few planks painted red, or a crow’s nest, perhaps a sail; but on occasion entire vessels, which had survived the assault of the belligerent surf, had borne up onto the shore, breaking open their hulls as wave upon wave threw them against the massive black boulders—the magma children of Mount Galigali—which formed the steep, brutal beach.

Today, however, there was nothing of any great size to see. Just a bicycle wheel, a tangle of old fishing nets in which several rotted carcasses were caught up, plus a great deal of trash that had been in the water so long it wasn’t really recognizable. There was one other thing, however, that the sluggish tide had delivered to the shore this day, something that lolled back and forth for a long while in the shallows as the teasing waters carried it up a little way and then claimed it again, only to roll it still farther with the next wave, until the sickly surf lost the strength to torment its plaything any further, and withdrew, leaving the ragged sack it had thrown up onto the black stones to remain where it was.

There, amid the fly-swarmed seaweed and the broken bottles and pieces of sea-worn wood (along with the occasional reminder that the Izabella had not returned empty-handed from the Hereafter: a very drowned chicken; a street sign bitten in half by one of the Izabella’s more aggressive occupants; a wooden crate containing several boxes of expensive whiskey; even—of all things—a laughing plaster pig, standing three feet tall and dressed in a chef’s regalia, while carrying a silver platter on which the pig was apparently quoted as saying: “Eat more pork!”) lay the body the waters had cast up on the Shore of the Departed.

It was the remains of a person, though the extensive damage that had been done to the body both from hungry fishes below and hungry birds above, did not at first make it easy to distinguish its gender.

But the signs were there, had there been anybody on that abandoned stretch of coast to see. It had the large hands of a male, and there was still an Adam’s apple in its much decomposed throat; its hips were narrow, and its shoulders broad. There were even a few signs of how this man might have looked in life. For some reason much of his face had been left untouched by the birds that had pecked at him as he floated, and it was still possible—if someone had cared to study his features closely—that at some time in his life somebody had sewn up his mouth.

The body had not gone unnoticed. Already some of the smaller scavengers that lived along the beach were appearing from under the stones they used as doors to their hideaways and cautiously venturing out to investigate the newcomer. The crabs that had been foraging in the rotting seaweed were now scuttling over the rocks toward this new meal. Most of them were small, their blue-gray shells barely as broad as the length of a thumb, but no sooner had they appeared than the bigger crabs, some of them twenty, thirty times larger than the foragers, appeared, pushing aside stones which then rolled or skipped down the shore and into the scummy water.

None of this sudden activity was missed by the bittamu birds that lazily circled the shore, huge scavengers that resembled the offspring of albatross and pterodactyl. They loosed full-throated shrieks of appetite and, making the subtlest of modifications in the angle of their wings, began a steady spiraling descent. But while they were still descending, a new claimant for the meat the Izabella had washed up came into view.

It had perhaps once been a crab, perhaps a crab of common dimensions. But it was much changed now, by something or someone who had corrupted it into this monstrous form with careless magic. It was albino, its shell marked with a symmetrical design of maddening complexity. It had no less than seventeen shiny black eyes, sitting atop twitching stalks, while its mouthparts worked in ceaseless finicky motion, as its massive claws rhythmically delivered the morsels it constantly picked up into the machine of its maw with a delicacy that their scale belied.

Scuttling sideways, like all of its clan, it approached the body. Several smaller birds, sharp-beaked mekaks who seldom took flight, preferring to dine, breed and die on the shore, were already dancing over the corpse in their delight at having so many treats to pick from. And in their squawking enthusiasm they failed to notice the approach of the albino. The creature, for all its size, was quick. It came at the frenzied mekaks at a rush, catching one in each of its scissor claws, and snapping each bird in half before they even had time to struggle.

The others, shrieking in panic, attempted to depart, flapping their ill-oiled wings in an attempt to get beyond the range of the crab’s claws. But no. Snap! And a third bird fell down headless. Snap! Snap! Snap! And a fourth dropped, quartered, to the stones.

Now the albino had the feast to himself. Even the bittamu birds delayed their descent, and circled above the beach unwilling to take on the beast below, however tempting the meal.

The crab assessed the body with its pincers and eyes, seeking out the best place to begin. It elected the hand of the corpse, taking hold of the wrist in its left pincer and lifting it up in order to snip off its fingers. But as it did so a long thread of life, its length spilling a sickly light, slid from the entrails of the body, where it had been nesting.

It let out a high-pitched squeal as it appeared; the strongest sound that shore had heard in many an age. It climbed up the corpse’s arm so fast that the crab had no time to prepare for its attack. The creature coiled around the claw, which still held the dead man’s hand. Livid bursts of brightness, more intense by far than the light its body spilled, now burst from it. They caught the shell of the crab’s claw in a web of lightning, which instantly tightened. The claw cracked wide open, shards of shell and pieces of its meat flying in all directions.

The crab did not have a mouth with which to voice its pain. It simply scrambled wildly to be away from its mutilator, its pincer legs sliding on the rot-slickened stones. But it wasn’t given a chance to escape. A second lightning thread had appeared from the coils of the corpse’s gut, and gathering itself into a coil had launched itself at the monster striking its eyestalks then dropping to the stones in front of the immense beast.

It instantly zigzagged beneath the crab, and drove its lightning-wreathed length at the crab’s belly with such force that the unthinkable happened. The crab—which had ruled the shore for a decade, slaughtering indiscriminately, even when there were rich pickings among the dead—was thrown over onto its back. Its barbed legs struck out wildly in an attempt to right itself, but could only pedal the air, which was suddenly thick with flies. For the first time in its life the crab made a thin whine of complaint, tinged with fear.

It had reason. It had only been on its back for a few seconds when its enemies slid up over the rim of its shell and onto its underside. There they rose and fell, rose and fell, their motion perfectly matched, until some invisible signal turned their dance into death. Together they drove their lightning-bathed heads into the crab’s segmented belly.

The crab’s whine became a shriek. Not of pain—the crab knew little of that—but of profound terror. This was its nightmare, its only nightmare: to be lying helplessly on its back while something that it had intended to make a meal of, devoured it.

But it was not a crabmeat dinner the bright thread sought. It was the fear itself, which it fed on, fattening on its cream, rich and thick then bearing its bounty, returning to the body from which it had come.

In the brief time that had passed since the waters of the Izabella had relinquished the corpse, rain clouds had blown in from the northeast. They were the first sign of a storm that had formed in the wildly unstable air above the edge of reality itself, where the sea dropped away into oblivion. Within two or three minutes the rain shower had become a deluge, which drove all but those few caught in the life-and-death struggle on the shore back into their hiding holes beneath the stones.

The crab, of course, had no hope of retreat. Exhausted by its panic it lay inert as the rain roared down on it. The storm hadn’t slowed the threads that were feeding on its terror. The bright threads came and went, harvesting the fear that suffused every part of the animal’s anatomy. They didn’t need the nourishment for themselves. It was their deceased creator, whose body they had never deserted, that they sought to reclaim with these gleanings of fear.

Had they been rational creatures with an understanding of death’s implacable hold, they would never have attempted to resurrect their host. He was dead, beaten and broken by the waters of the Izabella as they returned from the Hereafter. They had borne a chaotic freight of detritus from the streets of Chickentown. Storefronts, lampposts, cars, parts of cars, people in cars (some alive), roofs, doors, windows all stripped from houses, and innumerable remnants of the lives lived inside those houses: chairs, fridges, magazines, rugs, people, toys, clothes, and on and on; junk and life all thrown together in a soup of things lost forever. The threads’ host had been dashed against so many sharp, heavy, twisted pieces of trash that he might have died half a hundred deaths if he’d had them to die.

But finally a calmer current—the one that delivered his body to the Shore of the Departed—had claimed him. And now, in contradiction to the Shore’s very name, and in defiance of all the laws pertaining to the dissolution of the flesh, the devoted labor of the threads, carrying the food that the crab’s terror provided back to their maker’s corpse over and over, bore fruit.

The dead man moved. The crab did not see the miracle its nightmares had made possible. At some point in the coming and going of its fears’ devourers, the crab let go of life. The sluggish motion of its legs ceased entirely, and its whine sank away into silence.

The albino didn’t see the corpse it had almost dined upon twitch on its bed of black stones, nor its eyelids flicker open as the rain danced down on its all but fleshless face. As one life ended another began.

Nor was it for the first time. Christopher Carrion had drawn his first breath many, many years before, as a baby prematurely born. Now he took that breath again: a second first. This time, however, it was not a frail inhalation. This time, though the rain was still beating a tattoo on the stones as loudly as ever, the sound of the dead man drawing breath reverberated all along the shore, its resonance causing the stones beneath the stones, and those layered still deeper, to rattle against one another, the sum of their percussions so loud that the din of the deluge seemed inconsequential.

And as if driven off by that greater thundering, the storm clouds rolled inland, to pour their waters upon a place they had some hope of cleansing: someplace where the laws of life (and death) still held sway. The shore lay silent, except for the breathing of the dead man, and the sound of the Izabella as it threw its waves upon the stones.

The drumming of the stones finally ceased, its task complete. Carrion lived. His body was no longer the wretched, colorless thing it had been. Myriad forms of light were spilling into the air around it, memories of a life he almost lost. They seethed around him blazing with a living light this shore had not witnessed in many an age. In the flux of memories, Carrion began to whisper ancient incantations, designed to heal his broken body. In the time it took for the tide to turn, retreat, and turn again to once more climb the shore, the healing was complete. Healthy tissue spread over his wounds, sealing them and causing the rotted flesh to fall in strands and scraps onto the hard bed where he still lay.

The smaller crabs, the tiny, green sea lizards that had taken refuge beneath the stones, and the mekaks that had seen several of their kind killed by the Albino, returned now to the proximity of the man so as to feed on the putrid meat that the healed body had sloughed off. They had no fear of this man or his bright agents. He didn’t even see them as they scuttled over the stones around him, cleansing the shores of every last scrap of the death he had taken off in order to dress in life again.

After a time, he got to his feet. His memories still played in the darkness around him, their meaning—having been put to the purpose of Carrion’s rebirth—eaten away, leaving the darkness surrounding him swarming with the remnants of a life he’d lived once, died too. It was well lost. He would not make the same mistakes again.

The screech of metal on stone stirred him from his ruminations. He looked toward the water, and found there the source of the raw sound. The incoming tide had brought another souvenir of Chickentown to the Shore of the Departed. An entire truck, missing three of its wheels but still containing the slumped body of its driver, securely held in his seat by his seat belt, was being delivered to the shore.

Carrion’s face had betrayed no trace of feeling until now, when the subtlest of smiles appeared on a mouth still marked, even after his revival with the scars of his grandmother’s handiwork: the lines where she’d sewn his lips together for speaking the word love. He raised his hand to his mouth and ran his fingers over the scars. The smile died, not because Mater Motley had done him harm, but because she’d been right. Love was sickness. Love was self-slaughter. Love was poison and pain and humiliation.

He was reborn to be love’s enemy. To destroy it, utterly.

The thought gave him strength. He felt the power in his body surge, and with it a sudden desire to celebrate his return into the living, tender, fearful world.

He lifted his arm and pointed at the truck that was still in the water, the surf surging around it.

“Rise,” he told it.

The vehicle obeyed instantly, lurching violently as the water poured out of its engine. The driver lolled around like a drunkard at the wheel, as the truck continued its ungainly ascent. At Carrion’s feet the loyal nightmares, which had masterminded his return to life, fawned and cavorted as they watched their naked lord at play.

Carrion dropped his right hand to his waist, palm out, and the nightmares sprang to meet his fingers, coiling themselves up and around his wrist and arm so as to reach the precious place where they had been made: his head. Once they had swum in a collar filled with a soup of sibling terrors, which he had drunk and breathed. They would again, soon. But for now they made two blazing rings around his neck, and were in their heaven.

Carrion watched the truck ascend for a little while longer, and then uttered a syllable ordering its immolation. It instantly blew apart: a fireball of yellow-and-orange flame from which the burning fragments fell like tiny comets, meeting their reflections and extinction, in the sea. Carrion turned his gaunt, tragic face heavenward to watch the spectacle, and a single bark of laughter escaped his lips.

“Ha!”

Then, after a moment:

“What’s a resurrection without fireworks?”

Chapter 24

At the Preacher’s House

MALINGO ROWED THE LITTLE boat in the direction of Ninnyhammer. It wasn’t an Hour with the happiest of memories for either of them, given that Malingo had been Kaspar Wolfswinkel’s slave there for many years and Candy was very nearly murdered by the wizard in the process of escaping. But dark as their associations with Ninnyhammer were, the island was still the closest place to find a ferry that would take them to the massive harbor in Tazmagor on the Hour of Qualm Hah, which would ultimately lead them to the Nonce, and therefore to Finnegan Hob.

When they had reached Ninnyhammer, they decided upon a ferry called The Sloppy. And once they had bought their tickets, waited in line to board, and finally found chairs on the upper deck of the small steamer, the stresses of recent events took their toll, and Candy very soon began to doze.

“If I sleep . . .” Candy said, already halfway there, “I might go dream walking.”

“You mean sleepwalking?”

“No. This is that thing I told you about.”

“Ah. I remember. The Hereafter. Are you sure you’re safe there?”

“Yes. Of course.”

Malingo smiled. “Good.”

The ferry’s captain blew three blasts on the horn, sending plumes of white steam into the night sky. That was the last thing Candy knew of their departure. As the third plume floated to darkness, so did Candy. A blanket of sleep came down, and the ship, the sea, and stars all went away.

She didn’t rest in a dreamless state for long. By the time The Sloppy was out of Ninnyhammer’s harbor, Candy’s dreaming soul had gone home to 34 Followell Street.

She woke in the kitchen. It was daytime in the Hereafter. She glanced up at the clock above the fridge: a little after three. She went to the sink and looked out into the garden, hoping that her mother would be out there, sleeping in the rusted chair, her back turned to the house. Chance—or something like it—had arranged things perfectly. Her mom was indeed sitting in the old garden chair just as Candy had pictured her, asleep, which meant that this was indeed one of those precious times when they could talk together, dreamer to dreamer.

The first and only time they’d met this way before, Candy had left the encounter with a new determination to understand the mystery that had brought her into the Abarat in the first place, an impetus that had led, finally, to her separation from Princess Boa. Now she wanted to tell her mom all that had happened on Laguna Munn’s rock. Knowing that this dreamtime was unpredictable, and that they might be interrupted at any moment, she went straight outside.

She found her mother in exactly the same place she’d been when they’d met before, staring up at the sky. Melissa Quackenbush didn’t need to look around to know that Candy was with her.

“Hello, stranger,” she said.

“Hi, Mom. I missed you. I hope you’re not angry with me.”

“Why would I be angry?”

“Because I haven’t been home to see you since the battle.”

“No, honey, I’m not angry,” Melissa said, turning around now, and smiling at Candy. A true smile, full of love. “You’ve got a new life in the Abarat. And that day when the water came through—”

“The Sea of Izabella.”

“Yes, well, if what I saw that day is anything to go by, you’ve got your hands full. So no, I’m not angry. I worry about you. But things happen for a reason. I’ve always believed that. We don’t always know the reason. We just have to get on with things.”

“Everything’s going to be fine, Mom.”

“I know. I trust you. But”—she stopped and stared at Candy hard, her head turned slightly—“you’re different somehow.”

“Yes I am.”

There was a long moment of silence between them. Finally Melissa said, “So tell me everything.”

“It’s not very easy to explain.”

“What’s so hard about it?” Melissa replied with a little shrug. “You got rid of her.”

Candy laughed out loud, in part at her mother’s plain way of saying something that had seemed so difficult to put into words, and in part out of surprise that she knew.

“Who told you?” Candy said.

“About the Princess? Diamanda told me. The one with the long, white hair. The oldest of the women of the Fantomaya.”

“What did she tell you?”

“Not much really. Not about the Princess herself. But that you wouldn’t need to know anything.”

“She’s gone now. It was hard. Somebody died because of it. But I had to have her out. She’s bad, Mom. And I never knew. I never realized she was there inside me. And now she’s gone—and what she did when I let her go—” She shook her head, knowing she’d never find the words. “Seeing her clearly. This . . . monster who’d been inside me all that time.” She took a deep breath. “Did you ever see that in me? Any sign?”

“Of what? Of something bad in you?”

“Evil?”

“Lord, Candy, no. Never. Of course you had your little secrets. And you were always quiet. There was something special about you. I think even your dad felt that. But evil? No.”

“Good. I was afraid . . . you know how you hear about how people repress things? Bad things? So bad they can’t admit that they did them so they forget them?”

“Well, I wasn’t with you every minute of every day for all those years, but if you’d really done something bad—”

“Evil.”

“—I think I would have at least had some clue.”

“But nothing?”

“Not a thing. If this Princess is as bad as you say she is, I think I would have known if she’d shown herself.”

“But she did, Mom.”

“When?”

“All the time. She was part of who I was. Otherwise how would you have known that something was different? You felt it as soon as you saw me, didn’t you?”

“Yes.” She studied her daughter again, with eyes full of love as before, but tinged with a hint of fear. “But now you and she are separated. You’ll stay out of her way, I hope.”

“As long as she leaves me and my friends alone, I hope I never lay eyes on her again.”

“Good. Nobody needs bad people in their lives.”

“Mom, you don’t need to worry. Because when I’ve seen all my friends and I’m sure they’re okay, I’m coming home.”

“Home here?”

“Yes.”

“To stay?”

“Yes, to stay. Why do you sound surprised? This is my real home. With you and Dad and Ricky and Don . . .” Now it was Candy who did the face watching. “You don’t seem very happy about it,” she said.

“No. Of course I’m happy. To have you back home would be wonderful. But . . . things aren’t the way they were before the flood. A lot of people blame you. If you came back, they’d arrest you and interrogate you until they could find something to accuse you of. You opened their eyes to another world, darling. They’ll never forgive you for that. I know they won’t. There are a lot of cruel people in this town. There always were. But now there are a lot more.”

“I never thought about that,” Candy said. Her mother’s response had blindsided her. She’d always assumed there’d be a way. “People can forgive, right?”

“I’m afraid this is only the beginning, Candy. Something really terrible’s going to have to happen before ordinary folks come to their senses.”

“Where’s Dad?” Candy said, changing the subject.

“Well . . .” Melissa took a deep breath. “He’s at church.”

“He’s what?”

“At church. He’s preaching, believe it or not. He does it every day now.”

Candy wanted to laugh; of all the strange things she’d heard recently, the idea of her father heading to church to deliver a sermon was by far the strangest.

“I know how ludicrous it all sounds,” Melissa said. “Believe it or not, Ricky goes too. He has a lot more respect for your father these days.”

“What about Don?”

“He doesn’t have any interest in any of this. He stays in his room a lot these days.”

“This is too weird. Where does Dad preach?”

“He calls it The Church of . . . wait, let me get this right . . . The Church of . . . The Children of Eden. It’s on Treadskin Street, where the old Baptist Church used to be. They painted it green. It’s a really ugly green. But he’s really changed his ways, Candy. And people like what he has to say. Look. On the windows.”

Melissa pointed. There was a poster taped to the dining room window. And two more of the same design upstairs. Candy took a couple of steps back toward the house, so as to read what they said.

COME IN!

NO CONFESSIONS!

NO CONTRIBUTIONS!

ENTER AND YOU SHALL BE SAVED!

Candy was suspicious.

“He used to watch those TV evangelists just to laugh at them! And now he’s a believer?”

“Well, he isn’t drinking as much, which is a blessing. So maybe it’s doing him some good.” Suddenly, Melissa halted and the look of concern she already had on her face deepened. “You have to go now,” she said.

“Why?”

“I heard the front door. Your father’s back.”

“He can’t see me, Mom. I’m here in your dream.”

“I know that’s the way it was before, Candy, but like I said, things have changed.”

“No that much.”

As she spoke she felt a strange tingling sensation at the top of her spine, and slowly, slowly—almost as if in a nightmare—she turned back to see something her soul told her not to look at. Too late.

There was her father, coming out of the house. And he was staring right at her.

Chapter 25

No More Lies

CANDY HAD FACED MORE than her share of monstrous enemies in the last few months: Kaspar Wolfswinkel in his prison house on Ninnyhammer; the Zethek, crazed in the holds of the humble fishing boat Parroto Parroto; and the many Beasts of Efreet, one of whom had slaughtered Diamanda.

And not forgetting, of course, the creature who’d waited for Candy in the house where she’d taken refuge after Diamanda’s death: Christopher Carrion.

And the Hag, Mater Motley.

And Princess Boa.

But none of these monsters prepared her for this confrontation, with her very own father. Here he was, and he could see her.

Things had changed, just as her mother had warned.

“You thought you’d slip in here and spy on good Christian people without being seen? Think again. I see witches very clearly.” He held up the Bible he was carrying in his hand. “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live!”

This sounded so utterly preposterous coming from her father’s mouth that she couldn’t help but laugh. His face, which had always gone red when he flew into a temper, instead became pale, draining of blood.

“You mock me, you mock the Great One,” he said. His tone was calm, remote. “Do so if you wish. Laugh yourself into the flames of perdition.”

Candy stopped laughing. Not out of fear, but out of puzzlement. Her father had changed. The puffiness had gone from his face, and there was a new intensity in his eyes, replacing the blur of beer. He was leaner too. The extra pounds that had softened his jawline had gone. Nor was he combing his last few hairs over his head from side to side in a pitiful attempt to conceal his loss of hair. He had shaved it off. He was now completely bald.

“I don’t know what your mother’s been telling you, but I’m sure it’s lies,” he said.

“She just said you and Ricky go to church together.”

“Oh, indeed we do. Those of us with brains in our heads have seen the light. Ricky! Come out here! We’ve got a visitor.”

Candy threw a glance up at her mom. There were so many contrary emotions fighting for Melissa’s face that Candy couldn’t figure out what she was really feeling.

“Your mother can’t help you,” Bill said to Candy. “So I’d put her out of your head, if I were you. There’s only one man of vision left in Chickentown these days, and you’re looking at him. Ricky! When I tell you to get out here, you do it!”

While her father was looking toward the house, Candy glanced down at the vest he was wearing. Even by Abaratian standards it would have been thought outlandish. It was made from a patchwork of various thick fabrics—one striped, one polka-dotted, one black—but possessing an odd iridescence. She knew she’d seen this odd combination of colors before. But where? She was still puzzling over the mystery when Ricky appeared from the house. Her brother’s hair had been shaved off as well and he looked skinnier than ever. His eyes looked huge, like an anxious baby.

He’s so afraid, Candy thought. Poor Ricky. Afraid of the man who’s supposed to be his protector. No, not afraid: terrified.

“I was getting a clean T-shirt, Dad—I mean, Reverend, sir.”

“I don’t care what you were doing,” Bill snapped. “When I call you, you’ve got how long?”

“Ten seconds, Dad. No. I mean—sorry, sir. Reverend. I mean, Reverend.”

“Finally, the boy says something I can bear listening to. Now, I want you to take a deep breath, boy. And I want you to rest that stupid, stupid, stupid brain of yours. Do you understand what you need to do?”

“I guess so.”

“It’s real simple, son. Just don’t think.”

“About anything?”

“About anything. I just want you to close your eyes. That’s good. You’re perfectly safe.”