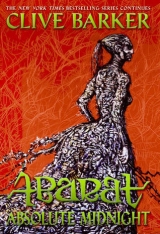

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

The effect upon Mater Motley was catastrophic. Each time one of the dolls came apart, her body convulsed, the scale of the motion mounting, so that she was quickly reduced to the status of a doll herself, helpless in the grip of forces she could not control.

It was not for want of trying. Twice she had attempted to summon up wieldings to drive Zephario back, but the violence with which she was being thrown around robbed her of the breath to finish them. Once only did she manage to utter four words, her eyes upon Candy as she spoke them:

“I WILL FIND YOU,” she said.

It was an uninspired response to the exquisite complexities of all that had come before, but Candy knew the viciousness of the woman cursing her too well to take the words lightly. Yes, the Empress of the Abarat had been cast down from her place of power. And yes, the souls she had most prized had been set free, the remnants of their prisons hanging off her dress, gutted. Yes, she was weak at that moment, and could perhaps have been destroyed.

But none standing or lying or kneeling there knew how it might be done. Minutes before she had been the very image of Imperial power, descending the flank of Mount Galigali with an army of burning assassins following upon her heels. Now she was in tatters. But she was still too dangerous a creature, and too unpredictable, for anyone to attempt to put her out of her misery.

In truth it was this most inward of wounds that saved Candy’s life, for after Zephario’s soul-passage through her body, Candy’s strength was utterly depleted. Had the Hag simply picked up a stone, she could have effortlessly beaten Candy’s brains out there and then and destroyed her nemesis in a heartbeat.

But the Empress couldn’t bear the idea of being seen in this broken, humiliated state, even though she’d won. The only memory of her she wanted anyone to take away from this battle was of her triumphant descent down the slope of Mount Galigali.

So, in a manner of restraint and decorum befitting a true Empress, she turned her back on the girl from Chickentown and very quickly made magical arrangements for her exit. She cast her eyes toward the bright place overhead where the comet of Carrions had briefly sundered the air and departed, leaving only a glimpse of that paradise to which they had gone, visible behind the door through which they’d passed.

The Empress was, of course, no longer wracked by the convulsions that the dolls had caused. All that unpleasantness was over. She could form words of summoning, sufficient unto the task of calling forth from the lava crust beneath her feet seven petals, enclosing her in a sheath of mottled gray and black, like a toxic flower that had yet to blossom. Only as it was about to close up, completely concealing Mater Motley from sight, did she utter one final instruction to the Other in her midst, in a language eons older even Old Abaratian: the ancient mind-words of the Nephauree. Candy didn’t need to know the language to understand what the creature had been told. The sounds of the words conjured pictures, which appeared with appalling clarity in her mind’s eye. She saw the ground crack. She saw rushing water. She saw the Void.

Then the petal shroud closed around Mater Motley, and sealed her up completely. And having done so, folded itself upon itself, and was gone. The moment the Empress was out of sight, every eye in the Abarat witnessed the appearance of what Midnight’s hand had cancelled: the light. The sacbrood fell from the sky, withered, and turned to ash.

It was a momentary triumph, for the Old Hag had left the Nephauree in her stead, asking of it one last favor: make sure that those many thousands who had witnessed her presence here did not live to tell of what they had witnessed.

Chapter 74

The Hammer of the Nephauree

“CANDY . . .”

Gazza was there, standing a little distance away from her, as though he wasn’t entirely certain that whatever he’d just witnessed happening was finally over, now that she was out of the fugue state that had put such a strange expression onto her face.

“It’s all right,” she said, looking up at him. She let him study her a while, to reassure himself that he did indeed have his Candy back with him. “I’m all right.”

“That thing . . .”

“The Nephauree?”

She glanced back over her shoulder. There were little bursts of brightness in the clots in the cloud of the Nephauree, as though its vast gaseous intelligence was speaking to itself, turning over possibilities.

“She instructed it to leave no witnesses,” Candy said.

“So now it’s going to kill everybody?”

“I would think so. If you were Empress of the Abarat would you want anyone—even a stitchling—to be able to report what they’d just seen? Poor Malingo. He’s already gone. I’m afraid we’re going to be following him very soon.”

“You’re not giving up?” Gazza said. He sounded appalled. “You, Candy Quackenbush? You can’t give up. What about the people whose lives you saved? The people here, thousands of them.”

“They . . . saved themselves.”

“Well, perhaps. But you showed them how to go on . . . and why.”

He looked away from her and attempted to clear his own eyes of tears with a quick wiping of his cheek.

“Please, Gazz . . .” she said.

“None of this was an accident, Candy; you meeting me, us coming here. I know you think you just brought more bad things here than good. And maybe Malingo would still be alive. But maybe he’d still be waiting for somebody to find him, and show him how to escape the wizard forever. You told me once, do you remember, not to think always of how something can happen. Only know they do.”

“I’ve got nothing left in me, Gazza. I couldn’t conjure a peanut, never mind a glyph.”

“We can still find a way out of here.”

“I don’t see how. We’re trapped.”

Behind them was the Void; in front of them the liquid fire of Mount Galigali, and to either side of the island the spumy waters of the Izabella, pouring off over the Edge of the World into Oblivion. Candy was right. There was no way out.

Meanwhile, the Nephauree was responding to Mater Motley’s last instruction; its virtually passive state became suddenly activated by the prospect of slaughter. The eruptions of light within each of the clotted areas threw out filaments of light, like lines drawn between constellations in the roiling darkness of the Nephauree’s internal universe.

As each line found its destination and moved on to the next, its brightness intensified, as though some vast mathematical equation was being solved in this geometry; a theorem concerned, paradoxically, with the ordered escalation of chaos. The speed with which the calculations took place continued to increase; it was only a matter of time before it reached critical mass.

“We’re not just going to stand here and look at it, are we?” Gazza said.

“No.”

“So we’re going?” Gazza said very quickly and softly.

“Yes.”

“Turn and run?”

“Better not to run, I think. We don’t want to draw attention to ourselves.”

“Got it,” Gazza said.

But the stitchlings, having been betrayed by their Empress once again, despite her promises of high remuneration, were beginning to understand that the Nephauree intended to massacre them as well, and took flight.

The Nephauree knew not where to begin its work of destruction. Finding a small window, together Candy and Gazza began to retreat, step after slow step over the baking earth. They had taken nine steps when the connection of black constellations ceased. The roiling motion in the interior went on, but now the darkness was being drawn toward a single place in the configuration. If the thing had an eye, then perhaps this was it.

“It’s watching us,” Candy said.

“Yeah, I get that feeling too.”

“Maybe we should . . .”

“Stop moving?” Gazza suggested.

“Yep.”

They stopped. It didn’t seem to help much. The eye continued to draw in strands of darkness from all around it. The point was very soon going to be reached where it could get no darker, nor any denser. Then surely, its killing power would fly.

The darkness flickered. Candy glanced at Gazza, and as she did so one of the stitchlings to the right of the creature lost its nerve, and turned to run. The Nephauree turned too. Not its entire body, just that little part within which the dark-amassing eye was set. A brief glance, sending a blur of shadows forth, and the stitchling—which had been one of the bigger brutes—was gone, as though the darkness had simply devoured it. Candy and Gazza turned and ran. And it hurt. Oh, how it hurt! Though the channeling of Zephario’s soul had been traumatic, and Candy’s body ached just about everywhere, it was, strange to say, a good hurt, a pain that made her aware of how alive she was, and how good it felt to be alive.

That was something worth running for, wasn’t it? To have more life, yes, more time to see the miracles of the Hours, and to help heal its wounds, more time to keep the company of the young man who was running as hard as she was beside her. All this raced through her mind as her body, filled with fury and gratitude, carried her over the broken ground—all this, and one other thing: the mystery of the Twenty-Fifth Hour, the Time Out of Time. There was a mystery being guarded there about which she knew nothing, except that it existed, and that she would never know the Abarat until she had solved it.

So much still to do: to explore, to solve, to feel. She couldn’t die yet!

But it was hard ground to race over, and they would have stumbled several times if each had not had the other to keep them from falling. They had a third companion, though Candy had not yet glimpsed it yet. One of the Abaratian seagulls had apparently decided to keep them company as they ran. Candy could hear its huge wings flapping somewhere overhead, and once she thought she saw it for a moment but it was such a brief glimpse—and what she saw was so large and preposterous—that she assumed her hallucinating senses were playing tricks. There was no doubt that the bird was keeping up with them, however. The more distance they were able to put between themselves and the Nephauree, the louder its wingbeats became. Finally, Candy slowed long enough to glance back. It was hard to judge how far they’d come.

The landscape had changed, even in the short time they’d been running. The wind had shifted, and the smoke from the volcano was drifting north, toward the Edge of the World. It obscured almost completely the remains of the Stormwalker, along with most of Mount Galigali’s northern flank. It only thinned out as it came close to the Nephauree. Or was it that the smoke had been consumed by the creature? That made sense. There was a jaundiced taint to the Nephauree now, as though it had somehow inhaled all the sulfurous filth in the cloud, and plucked up by its own devices shards of white-hot stone that hung like nascent stars in the Nephauree’s universe.

She took all this in—the smoke, the stolen yellow tainting the Nephauree, the bright white stars—in one brief glance. Then, realizing what she had not seen, looked again.

The stitchlings had gone. The burning ones, the ones that had just a flicker of fire here and there, and even those that had emerged from the wreckage whole: all of them, gone. The Nephauree had destroyed them all. Now the Nephauree had nothing left to delay it. Candy and Gazza were its only targets. And after them it came.

Candy didn’t look back a third time. She didn’t need to. She could feel the motion of the alien as it closed in on them; a profound disturbance in the ground over which she and Gazza were running.

There were people coming to meet them from the crowd of survivors at the far end of the island. And leading that crowd was John Mischief, arms outstretched. The gesture was optimistic, but the expression on his face was not. Even at this distance Candy could see that Mischief’s eyes were looking past Candy and Gazza. He was looking at the Nephauree. And he could see something terrible beyond words was about to happen.

“Bad news,” the bird said. “It’s attacking.”

Candy’s heart jumped, hearing the voice of the creature.

“Malingo?”

She slowed her run looking for the bird and, failing to find it, stopped entirely. Suddenly, down it swooped to hover in front of her. It was indeed Malingo. Or rather his head, the wound of his neck closed up and the leathery outgrowths on either side of his head flapping to keep him in the air.

“You’re alive!” Despite their desperate situation she couldn’t help but laugh: “Ha! Look at you!”

“This is how geshrats are born,” he said. “Heads with wing-ears. Our bodies are replaceable. I’ll just grow a new one when this is all over.”

“You never told me.”

“You never asked.”

“Well, that’s the strangest thing I’ve ever seen,” said John Moot.

“I disagree,” said John Serpent.

“Of course you do!” said John Mischief.

“Hey! I’m glad Malingo’s alive too,” Gazza said, “but we still have a problem.”

The Nephauree was no longer pursuing them. It had halted, twenty yards or so from Candy, Gazza and Malingo. Though Candy had seen countless images of power in her journeys through the Abarat, she’d never witnessed anything quite the equal of this. It was immense: a looming mass of contradictions. Despite its gaseous-liquid form there were places where the clotted darkness had a steely sheen to it, and others where it seemed the fine lines she’d seen drawn on its darkness had been etched there on countless previous occasions, an intricate matrix of line upon line upon line, darker even than the darkness into which they’d been scratched.

“Oh dear,” said John Fillet.

“What’s it doing?”

“Nothing good,” Candy said.

There was an insistent downward motion to the darkness now, the force of its substance pressing upon the solidified lava. It cracked open: jagged ruptures in the ground, which rapidly spread toward Candy and Gazza. There was nothing mysterious about either the motion of the fissures or of the light blazing out of them. The fissures were under the control of the Nephauree and they opened onto the molten magma that ran beneath the island.

Their way back to Mischief and the rest of the survivors was now denied. The widest of the fissures—seven feet wide and getting wider—had clearly been created to cut them off from their friends. They were being herded toward the northwestern corner of the island, where the waters of the Sea of Izabella became a roaring-white frenzy as they plunged helplessly on past the coast of Scoriae and over the Edge of the World. There was no real shore. The black lava rock simply sloped a little steeper before it met the panicking waters as they went to meet Oblivion.

The Nephauree was a stranger to itself, its mind a shadow on the wall of a chamber where the worst atrocities one living thing could visit upon another were commonplace. All it knew was the processes of fear, and how to multiply them. In the case of the young witch and her friends, it simply drove them back toward the waters until they were trapped between two unpleasant deaths: to be plunged into the white waters of the Izabella and drowned, or to drop into one of the fissures and be cooked alive.

At least, this had been its master plan. But the fracturing of the ground wasn’t proceeding as speedily as it had planned. There were more urgent claims upon its time right now than watching the little witch perish. It had come here to witness the elevation of the woman Mater Motley, into whose hands its species’ priests had put great power, for reasons more to do with their own Grand Designs than in service of her Imperial ambition. But she had underestimated the enemy, despite the elegance of her plotting.

The battle had been messier than the Nephauree had anticipated, but it had been won in the end. Even so, the priests who had dispatched the Nephauree here would not be pleased with the way things had gone. The sooner they had this news, the sooner they could make whatever strategic changes they judged appropriate. So the Nephauree could not afford to linger any longer. It needed this business with the girl and the fisherman over with, once and for all.

It needed to break the ground more effectively. And for that, it already had a plan. It willed its body to exude two horns of matter, into which it rerouted the darkness that had been dropped into its bowels. Now that same weighty darkness climbed up into the “horns” it had formed, turning them into vast hammers.

And down they came: two hammerheads of darkness that slammed into the wounded ground! Instantly, a fresh network of fissures appeared from the place where its hammerheads had landed. They zigzagged toward Candy and Gazza, separating them from the Johns, and causing every crack that had already gaped between the Nephauree and its victims to become even wider, creating a network of new fissures that drove the witch and her friends back and back and back, until they were at the top of the narrow shore that led down to the water’s edge.

The Nephauree lifted its hammerheaded horns again, reaching up even higher than it had previously, and brought them down like a judge slamming down his gavel to pass the final sentence. The shock wave it sent made the ground to gape everywhere, causing the tiny parcel of shore where the witch and her friends stood to be separated from the rest of the ground.

“We’re in trouble,” was all Candy could say.

Then the waters tugged at their little portion of ground with so much strength that it could no longer resist the demand. It parted from the rest of the shore with a violent shudder that threw Candy and Gazza to their knees.

Then the current caught it, and it was borne inexorably toward that place where the Sea of Izabella was lost to Oblivion.

Chapter 75

The End of the World

THE WATERS OF THE Izabella did more than simply carry the fragment of shoreline toward the limits of reality. It spun the makeshift vessel round and round, rocking it from side to side as it did so. But none of these chaotic maneuvers were sufficient to prevent Malingo from coming in to land on the slippery surface, with only the tips of his wing-ears to prevent him from sliding straight across the water-slickened surface to be dumped in the crazed surf on the other side, where he would certainly have drowned. Luckily Candy saw him slide past her and instinctively reached out, grabbing hold of one of his flailing wings, halting him before the worst could happen.

Not that there wasn’t an even more calamitous fate awaiting them all, just a few seconds away. Though the actual spot where the waters fell off into the Abyss was veiled in spray, there was no doubting its proximity. The closer the suicidal current brought them to their final moments, the less noise the waters made, their roar and rush fading as they dropped off the Edge of the World.

“You could still fly back,” Candy said to Malingo.

“Why would I want to do that?”

“Because we’re going to die!” Gazza said, sounding thoroughly furious. “I’d give my right arm for a chance to get off this damn rock.”

“Oh, really? And leave your lady?”

Gazza blushed.

“I knew it!” said Malingo.

“I knew it too,” Gazza said, looking to Candy. “From the moment I saw you. Don’t ask me how, but I did. I love you, Candy,” he said. “I’m glad I finally said it myself. I know it’s a bit late, but there hasn’t been a lot of opportunity, with one thing or another.”

Candy smiled at him.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Malingo said.

“What?”

“You’re just smiling at him.”

Any further words were drowned out by a vast silence, as the roaring sound of the waters’ chaos was stilled suddenly and completely, and the gray-blue mist that veiled the place where the waters actually fell away, cleared.

The currents that had carried the fragment of Scoriae to that place now vanished, for here the sea herself gave up possession of all form and will and power, and were tossed over the End of the Abarat, broken into innumerable beads of water, illuminated for a few seconds by the firelight, then extinguished. What had been, in the Reality from which the beads of water had now departed, an irresistible force was now no more than a million million drops falling away into the Abyss.

“This is it,” Gazza said.

Candy thought, After this, there’ll be no more magic, no more visions, no more love, or hope or—

“No, wait,” she said aloud. “Wait!”

“Who are you talking to?” Gaz said.

“I want more!” she yelled into the Void.

“More what?”

“Everything!” she told him.

“Why are you smiling?” Gaz said.

“We’re going over the Edge of the World!” Malingo said. “If there’s some good news, tell it, before we’re gone forever.”

“Later,” Candy said. “I’ll tell you later.”

They had run out of sea. The piece of land lurched and began to fall. But before it fell, Candy had time to look back toward the shore of Scoriae, and saw with heartbreaking clarity, John Mischief and his brothers. They were all watching her from a place so close to the water’s edge that every fresh surge of water threatened to carry them all away. Indeed, they almost seemed to be inviting that very fate, so close to calamity were they standing.

“Go back!” Candy yelled to them, though she very much doubted her words were audible.

John Mischief cupped his hands to either side of his mouth and the brothers tried yelling something in unison. But the air refused to carry the sound; the silence between shore and sea went unstirred. Then the little scrap of Scoriae tipped, and over the Edge it went, going where so much of the Sea of Izabella had already gone.

Down and down and down—

The John Brothers shouted the same word at the same instant: her name, of course.

“Cannndddeeeee.”

It did no good. It changed nothing. The waters carried Candy, Gazza and Malingo away, and down they went, out of the John Brothers’ sight.

“She’s gone!” Mischief shouted.

“She can’t have,” said Fillet.

“Well she has!” Mischief raged.

“But . . . but . . . she was going to make everything all right,” John Moot whimpered.

“It never would have worked,” Serpent said. “A thing like the Nephauree is beyond anybody’s power to resist. It’ll kill us all now.”

Serpent turned to look back at the Nephauree. For once his worst expectations were wrong. Those Who Walk Behind the Stars were departing. Promises were baubles with which ephemeral beings distracted themselves. The Nephauree had their own, far more important dealings. The beast had already swung its massive form around, and it was now moving off through the smoke toward the volcano. Its motion drew still more sulfur out of the churning air, and the Nephauree’s color deepened again, to a dazzling yellow. Then, as though it had drawn a massive surge of power from feeding off the smoke, it quickened its step, throwing open its cosmic robes as it did so, and like a dark sail filled by a following wind, it swelled up, and stepped off the ground, climbing the filthy air so quickly that in less than ten seconds it had gone from sight completely.

“Well, that was anticlimactic,” Serpent remarked.

“Only you, Serpent,” said John Fillet, “would complain because our executioner left!”

“I’m only saying . . . it’s a bit—”

“Shut up, Serpent,” Mischief said. There was deep rage in his voice. “Don’t you understand what this means?”

“Oh,” said Serpent after a pregnant pause. “Lordy Lou.”

His voice, for once, was scoured of every last drop of sarcasm or insincerity.

“She’s dead,” said John Drowze.

“Not dead,” John Moot said.

“Yes, Moot: dead.”

“We don’t know for certain,” John Pluckitt said.

“For the first and probably the last time, I agree with Serpent,” Drowze said. “It’s no use denying what we saw with our own eyes.”

“And what did we see?” John Slop said. “Not very much, it seems to me. I certainly didn’t see them die.”

“You’re clutching at straws, brother. They went over the Edge of the World.”

“That they did,” Drowze agreed.

“They fell, no question,” John Moot said.

“They’re probably still falling,” Fillet said.

“So what happens to them?” Slop asked.

“She’ll live,” John Serpent said with uncharacteristic enthusiasm. “If anyone’s capable of surviving falling over the Edge of the World, she is.”

John Mischief had lost his rage, and had gone back to contemplating the scene beyond the shore. Nothing had changed. The Izabella still rushed toward her dissolution, the fine spray that blurred the place where her waters fell away, which had briefly cleared and now concealed the place again.

“What are you looking at, Mischief?” Moot wanted to know.

“Everything. Nothing,” he replied.

“Well, that’s a waste of time,” Moot said. “We’ve got things to do. Important things.”

Mischief continued to look at the sea.

“Such as?” he said.

“Oh, come on, Mischief,” Moot said, “you know as well as I do.”

“Can’t think of anything.”

“Well, we got a body to bury for one,” Sallow said.

“That’s a pleasant prospect.”

“Then there’s the Eight Dynasties to deal with.”

“We can’t do that on our own.”

“We had a life before she came along,” John Fillet reminded him.

“Yes, John, but we were waiting,” John Mischief replied. “Weren’t we? That first day in the Hereafter was about more than a stolen key. We all felt that, didn’t we?”

“Yes . . .” said John Serpent. “. . . of course we did. I admit to it. I had a sense of . . .” He scoured his vocabulary for the right word. “. . . of imminence. That something of consequence was about to happen.”

“And then she came into our lives,” Mischief said. “And she changed everything.”

“Everything?” John Serpent said.

“Everything,” Mischief replied.

Chapter 76

And Beyond

FALLING AND FALLING AND falling through utter emptiness Candy, Malingo and Gazza quickly lost track of time; and—with no means of judging how far they’d fallen—of space too. The same colorless undifferentiated space to their left and to their right, and above and below. It didn’t even offer them the hope that darkness had offered: the chance that hidden somewhere was life, purpose, meaning. There was just a gray banality; a vast absence through which they tumbled without any way to judge the speed of their fall, or even, at times, whether they were falling at all.

They said nothing.

What was there to say, when there was nothing but nothing around you? There was no view to remark upon, no moon was rising, no trailing stars, nor sun departing, the sky in flames. Nor was there sky for it to fall from.

And still they fell.

Or perhaps only thought they fell. Dreamed it, perhaps.

Whatever the reason, it didn’t change their circumstances. To fall was—

to fall was—

to—

–fall.

Suddenly, there was something out of nothing. A flash of blue and scarlet, which instantly enveloped Malingo, and snatched him out of sight. Luckily he yelled his head off at this abduction and his long, loud cry appeared in the bland air, as though he’d scrawled it in a long trail of silver smoke. It was the first solid, or virtually solid, thing any of them had seen since they’d gone over the Edge. It wasn’t much of a lifeline, but it was better than the absence. So Candy caught hold of the silver strand, hoping that it wouldn’t go to nothing in her grip.

No.

It was solid.

“Grab hold of me!” she yelled to Gazza. He had his hand around her ankle before the words were out of her mouth.

Three thoughts came into Candy’s head at the same time, each demanding priority: one, that she hoped Malingo didn’t stop yelling; two, that they might not fall forever after all; and three, that she should have known, the moment she saw the mirrored word Abarataraba, that if there was a mirror of the islands along the horizontal axis, then it stood to reason that there’d also be one on the vertical. If to the left, then to the right. If above, then below.

While her thoughts fought, she pulled herself, hand over hand, along the length of the braided cry. She could see the length of it receding from her grip, and could fix her eyes upon the spot, no more than three hauling-lengths away, where it went from sight. What else could she do but follow her hands to the place, and find out the why and the how of it?

And then—Lordy Lou—Malingo stopped yelling. Candy felt the cord slacken, and let out a panicked yell of her own, which instantly formed a turquoise ribbon in front of her, like her breath on a winter’s day, before fluttering away when she stopped her cry.

She wasn’t going to let their chance to get out of the Void slip away. Whatever was on the other side of the wall of murk, it couldn’t be any worse than falling forever into Oblivion, could it? She forced her body to reach, reach—go on, fingers! Go on, hands!—beyond the end of the cord, which was already slipping up and away, carried by a gust of wind that smelled like lightning and pineapples.

Her fingers went now, disappearing completely. Her hands searched, probing through the Void . . . and touched something on the other side of the Wall of Nothingness. It was moist and warm, as though it had been painted by a loaded brush, and as soon as she touched whatever it was, whatever it was reached toward her with the same urgency. Dozens of boneless feelers as thin as string wrapped themselves around her hands and wrists.

“What’s in there?” Gazza wanted to know.

“I’ve no idea,” she told him. “But it’s alive. And it’s got hold of me. It’s pulling.”

“Does it hurt?”

It didn’t, she realized. It was a tight grip, but it didn’t mean her harm.

“It’s all right,” she murmured.

“What?”

“I said: it’s all right.”

She saw a gleam of bright columns ripple past her face.

“What was that?”

The word that went by. It was written in turquoise on a strip of air the color of mangoes.

“Malingo?”

The three syllables came out of her mouth, and flowed in purples and blues in a woven streak of sound and color.

“Yes?” he said.

“I’m not afraid,” she told him.

Again, her words poured out in woven stream of color: red, purple, blue. . . .

“Oh, will you look at that. Words like ribbons.”

And out the words came.

Words like ribbons.

Green and yellow and orange.

“What’s happening?” Malingo said. “I just saw my name fly by.”

“I know.” She reached out toward the source of the tentacles. A gust of wind blew from the place where her hand was. She felt it on her face. She heard it telling her, as winds will: