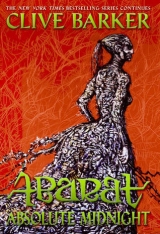

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Silent tears ran down Betty’s cheeks. Clyde hugged her.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “We’re going. The three of us.”

“Why is Mater Motley doing this?” Tom wanted to know.

“Because she’s a venomous piece of work,” John Serpent said. “And yes, I do realize a man called Serpent shouldn’t be tossing words like venomous around, but I’ve plenty more. She’s a vicious, loathsome, life-hating monster. I vote we skip the trip to the Yebba Dim Day and go straight to Gorgossium and call her down from her tower.”

“And what do we do if she comes down?” John Slop said.

Serpent didn’t offer up a reply.

“I think we should start walking down to the harbor while we talk,” Candy suggested. “We have to find a boat.”

“We should get three boats, then,” Geneva said. “I’ll go to the Nonce and find Finnegan.”

They had emerged from the market by now, and on the quieter street that took them back down toward the harbor. They were about to talk at a more natural volume, though Candy dropped her voice to a whisper and shared the other piece of information regarding Mater Motley’s plans: the part about the beasts.

“Lordy Lou,” Geneva said. “This is very bad.”

“And the part about the darkness wasn’t?” Mischief said.

“Are there a lot of creatures hidden away in the darkness?” Tom said.

“Oh yes,” said Eddie.

“How do you know?” Candy said.

“I wasn’t always a great actor,” Eddie said. “Before I took to the stage I made a nice business out of tracking down the Ziaveign and putting them out of their misery.”

“Zia-what?” Candy said.

“Ziaveign. Eight Dynasties’ destroyers and fiends.”

“This gets worse and worse,” said John Slop, looking rather pale.

“Did you say you put them out of their misery?” Mischief said.

“I worked with my two brothers,” Eddie said, “and yes, we did kill them when we were able to do so. Of course that was much more expensive. Much too expensive in the end. It cost my brothers their lives.”

A heavy silence fell on the company.

“I’m sorry,” Candy said finally. “That’s terrible.”

“They were fine, brave men. But the Eight Dynasties are strong. They may have been in hiding a long time, but that doesn’t mean they’re dead. They’ll rise up. That’s what Mater Motley is counting on.”

“She didn’t do all this alone,” John Mischief said. “She had help from that wretched grandson of hers.”

“Well, at least he’s dead and gone,” Geneva said.

Candy couldn’t bring herself to keep the truth from these people, who had done so much for her, any longer.

“Actually . . . he’s not,” she said.

“You know this for a fact?”

Candy nodded.

“How?”

“It’s complicated,” Candy said.

“What’s complicated about a man who lives in a fishbowl, pickled with his own nightmares?” Mischief replied. “And who has almost taken your life on several occasions? He’s dreck, dirt, excrement.”

Candy remembered her first glimpse of him in the alleyway. She’d thought something very similar: that Carrion was indeed made of filth. But in the end that was the fate of all flesh, wasn’t it? Everything decayed, went back to dirt, to the earth. But that wasn’t the whole story. People weren’t just walking sacks of meat. Unlike Carrion, she’d started to understand that there was something eternal, underlying, in everyone, perhaps even everything. A soul, for want of a better word, which—even when time had dimmed her sight and dulled her memories—would burn as brightly as it burned now.

Even if her memories seeped away, the sweet and sour of her life stolen from the meat of her mind, her soul would know its way to the net of remembrance that was being cast out over her life and all that touched it, gently retrieving the details of every moment. Cast out over and over, world without end. It wasn’t so surprising that these thoughts were being discussed in the room at the back of her head, while in the front of her mind the part of her that was in the here and now continued to talk with her friends. If ever there was a time in her life that she needed the comfort of this faith in the Eternal, it was Here and Now. She was part of a struggle that was older than life: the battle between Light and Darkness.

She was certain she belonged in this moment, in the company of these loving friends. She was here, in this world she loved so much, to play a part in its future. She didn’t understand, nor even particularly care to, how she had come to have a part in the approaching struggle. But everything she’d done since she’d first come here—her meeting with Malingo; with Wolfswinkel; her visit to the Time Out of Time; her pursuit of her own secret history that she’d pieced together from many sources; her strange relationship with Carrion; and her final liberation from the Princess Boa—all of it had been a preparation, an education, for being alive at this moment.

“What are you thinking about?” Malingo inquired.

“Everything,” she replied.

The atmosphere down at the harbor, which had been so odd when they’d got off the ferry, was even odder now. Some of the seabirds were still there, sitting in silent rows like bored jurists awaiting the beginning of a trial. But most of the people had left, and those who remained were gathered around a makeshift pulpit from which a crazed minister with long white hair and one ragged wing was preaching to them.

Candy listened to the creature talk about how the righteous would find their way to the light and the rest go into darkness; that was all she could stomach. She blocked its voice out, and looked in the opposite direction only to find that the missing seabirds had also found themselves a spiritual leader. Having forsaken their perch along the harbor wall they were now gathered in front of one of the shuttered restaurants, attending with many a beady black eye to a very large but very antiquated bird that looked like an albino vulture with a touch of pterodactyl in its blood. It was addressing its congregation in a language of crawings and chitterings, which was a great deal more complex, even eloquent, than the screech of a seagull.

As for the captains and crews of the small fishing boats that were tied up alongside the quayside, they had all departed, presumably to be with their families at this troubling time, or to drink in solitude.

“So now what do we do?” said Malingo, surveying the deserted dock.

“We choose boats that look sturdy and are fueled up, and we take them,” Eddie said.

“Just take them?”

“Yes! Lordy Lou, this isn’t the time to be arguing the moral niceties of the thing. There’s nobody here to barter with anyway.”

“Do we have to take boats?” Clyde said. “What about one of your glyphs?”

“I think we could probably conjure up a glyph between us but trust me, we don’t want to be in the air right now. Not with those things up there.”

“We’re safer on water,” Tom said.

“I trust Mama Izabella,” Candy said. “She’s not afraid of the dark. So we take some boats, yes? We can apologize when the lights go on again!”

“I wish there were some weapons we could lay our hands on too,” Geneva said.

“Maybe some harpoons?” Eddie suggested.

“It’s worth a look . . .” Geneva said. “I’ll take whatever we can find. We don’t know what we’re going to be up against.”

“The worst of the worst,” Eddie said grimly. Since he’d confessed his monster-trapping past, and the grim price it had cost his brothers, Candy realized that Eddie had nothing left to lose. The sight of his pain made her speak up.

“We’re all going off in different directions,” she said, “and who knows when we’ll see one another again. Or even if. So I just want to say that I love you. And I’ve been blessed to have this time with you. I want you to know you’re the best friends anyone could have.”

She looked from face to face as she spoke, not even attempting to put on a smile. If she’d understood Carrion correctly, then this Midnight would mark the end of the Abarat as they’d all known it. And what would be left? An archipelago ruled over by the monstrous Empress, Mater Motley? Or simply a wasteland, destroyed by the poisonous work of the fiends this darkness would unleash?

As Malingo and Clyde searched for weapons, boats were chosen. Geneva, who was traveling in search of Finnegan, chose a small, sleek vessel that looked to have been designed for sport rather than commercial fishing. It was called The Loner. Two-Toed Tom took the helm of a vessel called simply Big Boat, which he, Betty, and Clyde chose for its size, given that they were hoping to evacuate more than just one person. Candy chose for sentiment’s sake a boat that reminded her of the harrowing journey on the Parroto Parroto: Malingo, Legitimate Eddie, and the Johns agreed to join her. John Mischief instantly had his brothers democratically vote him the Captain.

All three boats had lanterns hanging from their masts and from the eaves of their wheelhouses, but at Candy’s suggestion they went aboard several other vessels moored in the vicinity and borrowed their lanterns too. If they were truly going to meet a wave of darkness out there then they needed to be carrying as many light sources as possible. There was some debate as to whether they should go back to the market and get some provisions to sustain them, but before they could come to a conclusion on the matter it was taken out of their hands by the fact that six or seven of the potbellied minister’s righteous congregation had noticed Candy and her friends. They broke away from the assembly, yelling: “Thieves! You get away from those boats!”

“I’ll be going then,” Geneva said briskly. “I’ll see you all again soon. Travel safely.”

So saying, she fired up her boat and sped away from the dock.

The Big Boat, carrying Betty and Clyde, and captained by Tom, was right behind. The only thing holding up the departure of the third boat, The Piper, was dissention among the John Brothers about who was going to be second-in-command.

“We don’t have time for this!” Candy said. “Get moving! Right now!”

Her intervention had an immediate effect. The brothers grabbed the wheel and readied themselves.

The fastest member of the minister’s congregation was a young man with mottled purple-and-white skin and a very fierce look on his face. Without waiting for the others to catch up with him he leaped into The Piper, and went straight for Malingo, who was attempting to untie the rope that tethered the boat to the dock. Candy reacted straightaway, catching hold of the collar of his jacket and pulling the young man toward her. He wasn’t any taller than she was, but he was lean and strong and, despite the fact that he was trying to stop them, there was something in his eyes that—

He wrenched himself free and turned on Candy, yelling: “Stop! Right now!”

“Got no time!” Candy said, shaking away whatever it was she had felt a moment ago. “And no choice!”

There were yells meanwhile, from other members of the minister’s congregation.

“We’re coming, Gazza!” one of them yelled. “Don’t let them go!”

In a few more seconds, Candy knew, all would be lost. They’d never get away.

“Mischief!” she yelled.

At that very moment, The Piper shuddered as the engine turned on, and then jerked forward with such violence that Malingo, the piebald Gazza, and Candy were all thrown down onto the mess of nets and floats that littered the deck. Eddie, who was much shorter and therefore steadier, was the only one not to fall. He had found a large machete somewhere, and holding it aloft, he raced to the stern of The Piper where the rope still kept the boat from departing the dock. Candy sat up, throwing off a net stinking of fish in which she’d landed, only to see Legitimate, wielding the machete like a man who’d done it many a time and brought it down with all his strength, severing the rope that kept them from making their escape.

He did so with not a moment to spare. The rest of their pursuers were a stride or two from boarding The Piper. One of the men attempted to leap aboard the boat even as the rope was severed. The Piper sped forward, and the leaper landed in the water.

They were away! The only problem was their extra passenger: the youth called Gazza. He was still in a fighting fury.

“You!” he said, pointing his mottled finger at Candy. “I know who you are! The girl from the Hereafter!”

“Candy Qua—”

“I don’t care to know your name. I demand that you order your thugs to turn this boat around.”

“We can’t,” Candy said. “If you want to get off, you’ll have to jump and swim.”

The youth called Gazza pulled a short-bladed knife out of a sheath hanging from his belt.

“I’m not swimming,” he said.

“Well, we’re not turning back.”

“We’ll see about that,” Gazza said, and shoved Candy aside. Then, knife in hand, he headed toward the wheelhouse.

Malingo yelled a warning to Mischief, but the roar of the engine surely kept the brothers from hearing it. Gazza opened the wheelhouse door, and would have been through it, his knife raised, had Candy not lunged at him throwing one arm around his neck and slamming her fist down on the hand that held the knife. He didn’t drop it. But she managed to pull him away from the door, at which moment, by sheer chance, the boat cleared the harbor and hit the heavy swell of the open sea. The boat was briefly lifted into the air as it crested the first big wave, throwing Candy, with her arm still around Gazza’s throat, back onto the deck. He fell with her. On top of her, in fact.

This time he did lose the knife. And by the time all the blushing and scrambling and cursing and struggling to stand up again was over, Malingo had picked the knife up and Eddie, looking a lot more serious, indeed dangerous, than the short, green, egotistical comedian Candy had first met, had his stolen machete pointed at Gazza’s navel.

“I will gut you, sir,” he said, betraying a trace of actorly flamboyance in that last syllable only, “if you make any further attempt to do harm. I mean it. I can and I will. You can let go of him now, Miss Quackenbush. Unless of course, you feel there’s a reason to hang on to him that I hadn’t fathomed.”

Candy stared briefly into Gazza’s eyes.

“No,” she said, averting her gaze and feeling embarrassed but not entirely sure what she had to be embarrassed about. “He’s . . . fine. He’s not going to be stupid about this once we explain—”

“Never mind the explanations. All I wanted you to do was turn the boat around,” Gazza said.

The purple patches on his face had turned a very pale blue, and his eyes, which had shards of gold in them, were no longer fierce.

“You can still jump in and swim back.”

“I can’t swim.”

“We don’t have time for this,” Eddie said impatiently. “We’ve got work to do.”

“If he goes in the water,” Malingo said, “he’ll drown. I can’t have that on my conscience.”

“I don’t give two hoots about your conscience. The whole world is being overtaken by darkness and the dynasties—”

“We heard it, Eddie,” Malingo said.

“I know their names! All eight of them: Tarva Zan, the Binder, and Lailahlo, who sings babies to their graves. And Crawfeit and Quothman Shant, and Shote, who leaves plagues wherever he walks—”

“Is he okay?” Gazza said, looking at Candy, the colors in his eyes reeling around.

“No,” she said.

“—there’s Clowdeus Geefee, who killed my little brother. And Ogo Fro, who killed my big brother. Sent him down into a despair he never rose up from. And last—but very far from least—there’s Gan Nug, who talks to the creatures that are in waters, deep down below us right now.”

Mischief and the brothers had emerged from the wheelhouse to hear Eddie offer up his list.

“What’s going on out here?” John Slop said.

Gazza stared at Mischief and his brothers, and for the first time in the considerable while Candy had known the Johns, she saw them do something that was curiously eerie. All of them shifted their gazes and looked at Gazza at the same speed and the same moment. And then, all at the same time, they said: “What are you lookin’ at, kid?”

It was too much for Gazza. He dropped to his knees, presenting the diminutive Eddie with an easier target.

“All right,” he said, “I won’t fight. I won’t cause any trouble. I believe you. Whatever you say, I believe you.”

Candy laughed.

“That’s good to hear. Eddie, put down the knife. We already know he’s trustworthy.”

“Me?” Gazza said. “Absolutely. Totally and utterly. I’m with you.”

He looked up at her, the pastel motes in his eyes settling into blue irises in pale yellow eyes. They looked straight up at Candy, meeting her gaze and quickening her heart.

Chapter 36

The Shadow-Shroud

DESPITE THE CURRENT DEFYING power of the Kreymattazamar, which returned Mater Motley and her entourage back to Midnight’s island faster than any other vessel in the Abarat, and despite the speed with which she was transported from the harbor to the circular room atop her Needle Tower, the shadow shroud of the sacbrood had already begun to spread in all directions from the pyramids.

Such was the passionate bloodlust of the brood to be out and doing their murderous duty, that when the path to the sky became blocked they set upon one another with unbounded brutality. Very quickly the areas surrounding the exits of the pyramids were littered with the remnants of the weak or unlucky, who had perished before reaching the stars they had been born to extinguish.

But such wastage had been factored into the calculations from the beginning. They did as they were programmed to do. They rose up and they spread across the sky. They went east to darken the skies over Babilonium, southeast to cover Gnomon’s wilderness, in the midst of which stood its Great Ziggurat; and northeast to Scoriae, where the darkness overhead seemed to encourage Mount Galigali to stir up the fire in its belly and spit streamers of liquid rock into the starless heavens. North it went to Pyon, where the lights of Commexo City burned so brightly that its apocalyptic effect was not felt. On other parts of the island, of course, places so far uncivilized by Pixler’s influence, the peasant community thought the blanking out of all the stars was just one more show of power by the great architect, and resigned themselves to finally giving up their independence and going to the bright streets of Commexo City where they would add to the sum of beggars there. The same northerly advance also encompassed Idjit, where that island’s incessant lightning storms became even more violent, stirred up by the blinding of the heavens. Finally the cloud spread west, southwest, and south, erasing the moon and stars from the skies over Jibarish, and Ninnyhammer, and extinguishing the late afternoon sun that bathed Gnomon where there had been many oracles, all of whom were quite capable of seeing this approaching catastrophe.

Notwithstanding the egotistical attitude that had silenced most of them, a few had been foolhardy enough to speak of what they’d seen. All had been dead within the hour. The rest, having quickly got the message that this was a future that would be fatal to talk about, kept what they knew to themselves, or left Gnomon entirely thinking they’d be safer talking about the approaching apocalypse on some other island. But wherever they went—some to the Yebba Dim Day, in the hope of talking to the Council, a few to Yzil or farther—it all failed to change their own futures. Those who spoke their fears aloud were murdered within the hour, leaving the others two options: to live in silent anticipation of the world’s end, or to take their own lives before it came.

So the secret of Absolute Midnight had remained secure. And when the sacbrood rose up in their millions, the noise of their innumerable beating wings was like no sound those hearing it had ever heard before, nor would again. They were out. Out and up, covering the sky. And it wasn’t only the bodies and wings of the brood that were blocking the light. They exuded a thick juice called broodgrume from their abdomens, which dried to a dense, hard, shell-like substance within a few moments of being exposed to the air. They had been programmed generation upon generation that, once they were up above land and water, they were to completely empty their sacs of this broodgrume. The consequence? That they all would become helpless prisoners of their own secretion; countless millions of their insectile brains too simple to understand that the instruction to void themselves of the grume would be the first and only act they would perform in the world outside their hives.

There had been times when Mater Motley had trouble believing that such a massive number of living things, however simplistic their thinking, would do as they had been programmed to do so blindly. At such times she went to a secret and sacred place that she had never named aloud. Its name was Zael Maz’yre, and from it all dark blessings flowed. She had bathed in those blessings for many years, and in due course she would pay the price, gladly. But for now, there was pleasure to be had hearing creatures of every kind raising their voices in panic as the erasing darkness spread across the sky, wiping out star after star, blinding moons and blotting out suns. Even the constellations had gone. Every last star had been like candles in a hurricane.

People offered prayers to the divinities of every Hour, but outweighing the prayers offered to gods and saints a hundred to one were those prayers offered up to the most ubiquitous force for happiness in the Abarat—the Grinning Boy himself—the Commexo Kid. He was the savior to whom countless terrified souls called out as the shadow-shroud moved on, its layers of living brood and their excreted grume two or even three layers thick in some places. Jibarish was plunged into utter darkness. So too was Ninnyhammer, and the Rock of Some Distinction called Alice Point; and the Nonce, and the Isle of the Black Egg, and Huffaker, and Orlando’s Cap, and Hobarookus . . .

Cries of terror and panic still rose up out of the islands that were newly overtaken by darkness. But out of those that had first fallen under the influence of the shadow-shroud the fear was punctuated with a new and very particular sound: that of accusation. Who had done this, and why? Why? Somebody needed to own up to this crime and do so quickly or there would be consequences. On island after island, in Hour after Hour, people started to seek out anyone that was in some way odd, and found, in mere distinctions, evidence of guilt. The signs were usually very small—a harelip, a slow eye, a tic, a stammer—but all that mattered was that the voices of accusation were able to rouse a mob into believing that these innocents were in some way responsible for this terror.

Mater Motley watched all of this with gluttonous satisfaction. She had reports from Nightseers, seamstresses whose eyes were powerful enough to pierce the darkness even at its densest. On Gnomon she was shown a crowd of three hundred or more, having lit fires to illuminate an ancient place of judgment, start the business of dealing with those that their collective madness had decided were responsible for the death of light.

The leader of the mob was a little man with some Skizmut blood in him somewhere. His name was Dyer Mere, and he had elected himself as the leader of the court among the trees. He demanded that the three prisoners the mob had selected—two sisters, Juup and Namena Chantamik, and a sometime tax inspector called Theopolis Kalapao—confess their guilt. The mob was convinced that it was they who had brought this calamity upon the islands. The two sisters were sobbing and quite beyond saying anything coherent, so it fell to Theopolis to reason with the crowd.

They all knew him, he reminded them. Had he not always been honorable in his dealings? Had he not possessed a sense of what was fair and right? He had no knowledge of the monstrous powers that had been used to blind the heavens. He was a victim of this catastrophe, just as they were. Unfortunately for him, Theopolis the tax inspector stammered, and the more he realized he wasn’t winning the argument against his accusers, the worse his stammer became, until his words of self-defense, reasonable though they were, could not even be understood.

The crowd didn’t listen. The deaths of Theopolis and the sisters were swift.

“Now the culprits are dead,” Dyer Mere declared. “Their spell will be undone very soon. Unless, of course, there are more conspirators we have not yet rooted out.”

By now the darkness had reached the eastern limits of the Abarat, as it had to the north and south. It was as though the Abarat was a vast coffin and the sacbrood its lid. And still, when Mater Motley turned her gaze toward the pyramids, she saw the brood emerging from their hives like a black snake, their numbers apparently undiminished, rising to extinguish every last light in the skies, their programming so powerful, and their hunger so vast, that they cared not at all that those of their species who’d emerged an hour earlier were now trapped in a vault of bodies and solidified grume. All that mattered to each was the task they’d been programmed to perform. To any other subject—such as the suffering of their own kind (which they would soon share)—they were as blind as the Abaratians on the islands below.

Within forty minutes, the number of innocents accused of causing the darkness to descend, and summarily hanged for their wickedness, had risen from three to eighty-five. Among that number was Dyer Mere himself, who had overseen the executions of his own wife and son-in-law before the finger of suspicion had turned on him. Now he was dead. Strung up from the same branch from which his first victim, the stammering tax inspector, Theopolis Kalapao, had been hanged.

The same insanity had possessed mobs of frightened souls on every island. The spectacle of their panic turning to judgment and slaughter was not something Mater Motley had considered when she’d been calculating the way that the events of this Midnight would play out. But what came next she had foreseen: the arrival of the Ziaveign. The eight families of monsters and their vile hybrids who had been hiding all across the island, harboring their hatred, waiting for a long-promised darkness to spread across the Abarat, now came out of hiding.

The Old Mother had made it her business over the years to reach as many of them as possible herself, finding them in their grim sanctuaries, hidden from the light and its servants. So she knew many of the demonic creatures that now rose up to sew havoc among the tribes who had hunted them when their sacred suns and moons had been high and mighty. Now the skies were black, and the light-givers gone. In the dark the hunters were about to become the hunted.

There were creatures in this rising multitude that were as ancient as the elements. The Crawfeit, for instance, whose bodies were bone cages filled with flocks of burning birds; their heads black iron pots brimming with a vile stew of venom, angel’s grief, and human meat; their limbs lengths of burned muscles held together with hair and hooks, and arrayed with dagger fingers. They were not demons. The Abarat had no known hell. The Crawfeit, like the other seven Ziaveign from which root all forms of night-beast, each corrupted in its own particular way, sprang from the presence of cruelty, pain, and loneliness among the Hours.

The Old Mother caught sight of all the Fiends she’d hoped to discover as she scanned the islands. On Scoriae she found the Abarat’s first executioner, Quothman Shant, at his bloody work. On Soma Plume, she saw Lailahlo, the Queen of Murderous Song, leading a chorus of tiny Pulcinellas. The Binder, Tarva Zan, who wrapped the hearts of her victims in fire, was walking the silent boardwalk of Babilonium. Gan Nug was still standing at the highest point of The Great Head calling forth more horrors. At his feet, gazing up at him in adulation, were nine of his Preyers, or priests. Clowdeus Geefee she found on a boat, alone, the Izabella stained bloodred all around, while Shote, the Plaguer, she discovered seeding diseases in the fields of the Nonce, and on Huffaker, caught sight of Ogo Fro, who was entropy and fatigue incarnate, among a crowd of the wanderers lost in the dark.

It was a triumph for darkness. All eight of the Great Fiends had risen up and shown their faces. And if they were here, then their children would surely be here too. And their children. And theirs. None of them as powerful as their legendary forebears to be sure, but they still possessed the genius to terrify. The Old Mother was happy—at least as happy as she knew how to be. She had thrown a party in the name of darkness, and all the guests she’d most wanted to attend had done so.

The Twenty-Fifth Hour, however, had been entirely unaffected by the invasion of the sacbrood. It not only protected itself at sea level, effortlessly repelling the darkness that attempted to touch the shore, but it also defended the air above with a sheath that reached up into the stratosphere, and instantly cremated those sacbrood who, in their thoughtless conviction, treated the air above the Twenty-Fifth Hour like any other. It was not. The rules of physics were inverted over that timeless place.

Air that should have been lightless was instead pale yellow, while the stars, whether they were fixed or falling, blazed black against its brightness. The Twenty-Fifth had no intention of allowing the brood to invade its sacred air. Though the forces encircled the island, throwing wave after wave of forces against it, the power that the Hour emanated was too unpredictable to be overwhelmed. Finally, the brood seemed to comprehend that this was not a battle they could win, and left off the attack to move on to new conquests: some breaking north to the Outer Islands, others around the island to follow an easterly course.

The fact that the Twenty-Fifth had not succumbed irritated Mater Motley.

“You hear me make this oath, Maratien,” she said when word reached her that the brood’s attempts to get onto the island had failed. “Before very long, you will follow me as I walk up from the water’s edge into the heart of the Twenty-Fifth. And I will stand there as its owner, and I will sink it if I so choose.”