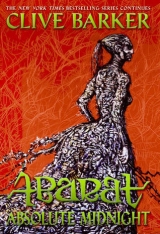

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Dedication

Johnny 2.0 Raymond

Mark Miller

Robbie Humphreys

Epigraph

There’ll be no sun tomorrow morning.

There’ll be no moon to bless the night.

The stars will perish without warning.

These lines proclaim the death of light.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: What the Blind Man Saw

Part One: The Dark Hours

Chapter 1. Toward Twilight

Chapter 2. The Council Speaks its Minds

Chapter 3. The Wisdom of the Mob

Chapter 4. The Kid

Chapter 5. Remnants of Wickedness

Chapter 6. Under Jibarish

Chapter 7. The Sorrows of the Bad Son

Chapter 8. Laguna Munn

Part Two: You, or Not I

Chapter 9. A New Tyranny

Chapter 10. The Sorrows of the Good Son

Chapter 11. Severance

Chapter 12. One Becomes Two

Chapter 13. Boa

Chapter 14. Empty

Chapter 15. Face-to-Face

Chapter 16. Laguna Munn Angered

Chapter 17. Snake Talk

Chapter 18. An EndGame

Chapter 19. The Price of Freedom

Part Three: Many Magics

Chapter 20. Tomorrow, Today

Chapter 21. Boa at Midnight

Chapter 22. Turning Away

Chapter 23. Cold Life

Chapter 24. At the Preacher’s House

Chapter 25. No More Lies

Part Four: The Dawning of the Dark

Chapter 26. The Church of the Children of Eden

Chapter 27. Interrogation

Chapter 28. Altarpiece

Chapter 29. Midnight has Wings

Chapter 30. Draining the Ghost

Chapter 31. The Flock

Chapter 32. Sacrilege

Chapter 33. No Stranger Now

Chapter 34. Unfinished

Chapter 35. Stealing Away

Chapter 36. The Shadow-Shroud

Chapter 37. Love and War

Chapter 38. An Old Trick

Chapter 39. Looking Forward, Looking Back

Chapter 40. Bones and Laughter

Chapter 41. Dragon Dust

Chapter 42. The Fiends

Chapter 43. Dark Waters

Chapter 44. Pariah

Part Five: Stormwalker

Chapter 45. The Business of Empire

Chapter 46. Talking of Mysteries

Chapter 47. Convergence

Chapter 48. Smiles

Chapter 49. Of Those Who Walk Behind the Stars

Chapter 50. Out of the Deep

Chapter 51. Father and Son

Chapter 52. Atrocities

Part Six: There is No Tomorrow

Chapter 53. Forgiveness

Chapter 54. The Empress in her Glory

Chapter 55. Below

Chapter 56. The Hand in Fire

Chapter 57. A Knife for Every Heart

Chapter 58. Now, Because

Chapter 59. A Whisper of Infinitude

Chapter 60. Abarataraba

Part Seven: Oblivion’s Call

Chapter 61. Missing

Chapter 62. The Volcano and the Void

Chapter 63. Pigs

Chapter 64. No Plan B

Chapter 65. Lullaby

Chapter 66. Love, Too Late

Chapter 67. Yat Yut Yah

Chapter 68. Deliverance

Chapter 69. For Every Knife, Five Hearts

Chapter 70. Nothing But Stones

Chapter 71. An Execution

Chapter 72. Truth

Chapter 73. Souls

Chapter 74. The Hammer of the Nephauree

Chapter 75. The End of the World

Chapter 76. And Beyond

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

What the Blind Man Saw

Dream!

Forge yourself and rise

Out of your mind and into others.

Men, be women.

Fish, be flies.

Girls, take beards.

Sons, be your mothers.

The future of the world now lies

In coral wombs behind our eyes.

–A song sung in Paradise Street

ON THE EARLY COAST of Idjit, where two a.m. looked south over the darkened straits toward the island of Gorgossium, there was a house, its facade much decorated, set high upon the cliffs. Its occupant went by the name of Mr. Kithit, and several others besides, but none of the names were truly his. He was known simply as the Card-Reader. The cards he read were not designed for games of chance. Far from it. He only ever used the Abaratian tarot deck, wherein a reader as expert as Mr. Kithit might find the past murmuring, the present in doubt, and the future barely opening its eyes. A decent living could be made from interpreting the way the cards fell.

For many years the Card-Reader had served the countless customers who came there in search of wisdom. But tonight he was done with serving the curiosity of others. He was done with it forever. Tonight, it was not the future of others he was going to find in the cards. They had summoned him to show him his own destiny.

He sat down and took one slow, calming breath. Then he proceeded to lay out a pattern of nineteen cards chosen by the will of his fingertips. Blind though he was, each image appeared in his mind’s eye, along with its name and numerical place in the pack.

There was Fear. There was The Door to the Stars. There was The King of Fates and The Daughter of Curiosity. Each card was not only to be read for its own values, but also calibrated against the cards surrounding it: a piece of mythological mathematics, which most heads could not fathom.

The Man Lit by Candles; Death’s Island; The Primal Form; The Tree of Knowing . . .

And of course the entire arrangement had to be set against the card that his customer—in this case himself—had chosen as his Avatar. In this case, he had elected a card called The Threshold. He had put it back into the pack and then shuffled the cards twice before laying them out by instinct in the Naught Hereafter Spread, its name signifying that all things the Deck contained would be here displayed: all reparations (the past), all possibilities (now), and all risk (henceforth and ever).

His fingers moved quickly, summoned by a call from the cards. There was something here they wanted to show him. He quickly understood that there was news of great consequence here, so he neglected the rules of reading, one of the first being that a Reader waited until each of the number of cards required for the Spread had been laid out.

A war was coming; he saw it in the cards. The last of the plots were being laid, even now, the weapons loaded and polished, the armies assembled, all in readiness for the day when Abaratian history turned the final corner. Was this the cards’ way of telling him what part there was for him to play in this last, grim game? If so then he would attend to whatever he was being taught, trust to their wisdom as had so many who had come to him over the years, despairing of all other remedy, seeking that which the cards would show.

He was not surprised to find that there were many Fire cards around his Threshold, laid out like gifts. He was a man whose life—and flesh—had been re-wrought by that unforgiving element. Touching the cards with his seared fingertip, it was impossible for him not to remember the merciless conflagration that had beaten him back as he tried to save his family. One of his children, the youngest, had survived, but the fire had claimed all the rest except his mother, and it had only granted her a reprieve because she had always been as pitiless and all-consuming as a great fire; a fire large enough to reduce a mansion and most of a dynasty to ashes.

In effect he’d lost everything, because his mother—crazed by what she’d witnessed, it was said—had taken the infant and disappeared into Day or Night, perhaps in her madness to hide the one survivor of her twenty-three grandchildren from the slightest hint of smoke on the wind. But the insanity plea had never been sufficient to quite calm the Card-Reader’s unease. His mother had never been a very wholesome woman. She’d liked—more than was good for an unbalanced spirit such as hers—tales of Deep Magic, of Earth-Blood Doing and worse. And it had troubled the Card-Reader more than a little that he had lost track of both his mother and son; it troubled him because he’d not known what they were up to. But even more because they—the one who had borne him, and the one he had fathered—were out there somewhere, a part of the powers assembling for the labors of destruction that were signaled everywhere in the lay of the cards.

“Must I come and find you?” he said. “Is that what this is? Do you want a sentimental reunion, Mother?”

He judged by weight how many of the cards he had so far laid down. A little over half, he guessed. It was possible the half he still held carried news of his last connection with Abaratian history but he doubted it. This was not a spread of specificities. It was the Hereafter Naught, the last apocalyptic gospel of the Abaratian tarot.

He set the unplayed cards down, and went to the door of his house to bathe his scarred face in the cast of the silver starlight. The years when the children of the village of Eedo, which was at the bottom of the steep trail that zigzagged up the cliff to his house, had lived in fear of him had long since passed. Though they would playact terror to amuse each other, and he played the growling monster to feed the fiction, they knew he usually had a few paterzem to toss over the threshold for them to squabble over, especially when—as tonight—they brought him something they had found along the shore to give to him. Today, as he stood at the door of the house, one of his favorites, a sweet hybrid of Sea-Skipper and commonplace child, called Lupta, came squealing to find him with an entourage of children following closely behind her.

“I have flotsammi jetsammi!” she boasted. “I have many. Lookazis! Lookazis! All thrown up by Our Gracious Lady Izabella.”

“You want to see more?” said her brother, Kipthin.

“Of course,” the Card-Reader said. “Always.”

Lupta grunted out instructions to her little gang, who noisily un-netted their catch onto the ground in front of the Card-Reader’s house. He listened with a practiced ear to the noise the find gave off: the objects were large. Some clattered and clanged, others rang like sour-noted bells.

“Describe them to me, will you, child?”

Lupta proceeded to do so, but—as was so often the case for haggling in the weeks since the persuasive currents of the Izabella had invaded the Hereafter, flooded Chickentown in Minnesota, and returned carrying some trophies of that other dimension with them—the objects that the tide had thrown up on the rocky beach below were not easily described or pictured, having no equivalent in the Abarat. Still the Card-Reader listened intently, knowing that if he was to understand the significance of the deck half spread in the darkened room behind him then he would need to understand the nature of the mysterious Humaniticks, some of whose artifacts, their details hard to make sense of when a man had no sight, surely offered profound clues to the nature of those who might unmake the world. Little Lupta perhaps knew more than she thought she knew. And behind her guesses, she was plucking up truths.

“What were these things made for?” he asked her. “Are they engines? Or toys? Are they to be eaten? Or maybe to kill?”

There was some frantic whispering among Lupta’s gang, but finally the girl said with absolute confidence:

“We don’t know.”

“They’re much beaten by the sea,” Kipthin said.

“I would expect nothing less,” the Card-Reader said. “Even so, let me put my hands upon them. Guide me, Lupta. You needn’t hesitate, child. I’m not a monster.”

“I know that. If you were, you wouldn’t look like one.”

“Who told you that?”

“I did.”

“Hm. Well, is there something here you think I might understand?”

“Yes. Here. Put out your hands.”

Lupta put one of the objects into his proffered palms. As soon as his fingers made contact with whatever it was, his legs gave way beneath him, and he fell to the ground dumping the piece of trash Lupta had given him. He reached down and searched for it, seized by the same fervor that caught hold of him whenever he was reading the cards. There was one significant difference, however. When he read the cards his mind was able to make a pattern of the signs he was seeing. But there was no pattern here. Only chaos upon chaos. He saw a monstrous ship of war, with his mother, aged but still as much a harridan as ever, commanding the waters of the Izabella to burst through the divide between its natural bed and into the Hereafter, its crazed flood ripping apart what lay on the other side.

“Chickentown,” he murmured.

“You see it?” said Lupta’s brother.

The Card-Reader nodded. “Being ripped apart.” He closed his eyes more tightly, as though he might blot out with a willed blindness the horrors he saw.

“Have any of you heard any stories concerning the people of the Hereafter?” he asked the children.

As before, there was frantic whispering. But he caught one of his visitors urging Lupta to tell him.

“Tell me what?” the blind man said.

“About people from a place called Chickentown. They’re just stories,” Lupta said. “I don’t know if any of them are true.”

“Tell me anyway.”

“Tell him about the girl. She’s the one everyone talks about,” said a third member of Lupta’s gang.

“Candy . . . Quackenbush . . .” the blind man said, half to himself.

“Have you seen her in your cards?” Lupta asked. “Do you know where she is?”

“Why?”

“You have, haven’t you?”

“What would it matter if I had?”

“I need to talk with her! I want to be like her! Everything she does people talk about.”

“Like what?”

Lupta’s voice became a whisper. “Our priest says it’s a sin to talk about her. Is he right?”

“No, Lupta, I don’t believe he is.”

“I’m going to run away one day. I am! I want to find her.”

“You be careful,” the Card-Reader said. “It’s a dangerous time and it’s going to get worse.”

“I don’t care.”

“Well, at least come and say good-bye, child,” the Card-Reader said. He dug into his pocket and brought out a few paterzem.

“Here,” he said, handing the coins over to Lupta. “Thank you for bringing the stuff up from the shore. Will you divide this between you? Fairly, now.”

“Of course!” Lupta said. And happy with their reward she and her friends went off down the road to the village, leaving the Card-Reader with his thoughts and the collection of objects the current, the children, and circumstance had brought before him.

The urchin and her gang had arrived at an opportune moment. Perhaps with the remnants they’d brought he could make better sense of the Spread. The cards and the trash had much in common: they were both collections of clues connecting what the world had been like in a better age. He went back into the house and sat at the table again, picking up the un-spread cards. He had only laid down another two when the card representing Candy Quackenbush appeared. It was easily identified. I Am They, the card was called. He could not recall having ever seen it before.

“Well, well . . .” he murmured. “Look at you.” He tapped her with his finger. “What gives you the right to be such a power? And what business have you got with me?” The girl on the card stared at him from his mind’s eye. “Are you here to give me harm or happiness? Because I tell you I’ve had more than my share of sorrow. I can’t take much more.”

I Am They watched him with great compassion.

“Ah,” he said. “It isn’t over. At least now I know. Be kind to me, will you? If it is in your power.”

It took him another six and a half hours from his speaking to Candy Quackenbush to finally deciding he was done with the Spread. He gathered up all of the cards, counting them to be sure he had them all, and then he went outside, taking them with him. The wind had picked up considerably since he’d been out here with Lupta and her little gang. It came speeding around the corner of the house, buffeting him as he walked toward the cliff edge, the pack of cards trembling in his hand.

The farther from his doorstep he ventured the more unreliable the ground became, the solid earth giving way to loose dirt and pebbles. The cards were becoming more excitable with every step he took out there beyond the cliff edge. Events they’d been unable to share until now were imminent.

Suddenly the wind picked up its strength, and threw him forward, as if to cast him into the world. His right foot trod vacant air, and he toppled forward—seeing all too clearly in his mind’s eye the waves of the Izabella below. Two thoughts came into his head at the same instant. One, that he had not seen this (his death) in the cards. And two, that he’d been wrong about Candy Quackenbush. He would not meet her after all, which saddened him.

Then two small yet very strong hands seized his shirt and pulled him back from the brink. Instead of dropping to his death he toppled backward, landing on top of his savior. It was little Lupta.

“I knew,” she said.

“Knew what?”

“You were going to do something stupid.”

“I was not.”

“It looked like you were.”

“The wind caught me is all. Thank you for saving me from losing my—”

“The cards!” Lupta said.

His grip on the cards was too weak. When the wind came gushing again it snatched them from his hand, and with what sounded like a ripple of applause as they slapped against one another, they were carried away, out into the naked air.

“Let them go,” the blind man said.

“But how will you make money without your cards?”

“Heaven will provide. Or else it won’t, and I’ll go hungry.” He got to his feet. “In a way it confirms my decision. My life here is over. It’s time I went to see the Hours one last time before they and I pass.”

“You mean they’re coming to an end?”

“Yes. Many things will end soon. Cities, Princes, things foul and things fine. All will pass away.” He paused, looking up sightlessly at the sky. “Are there a lot of stars tonight?”

“Yes. Lots.”

“Oh good, very good. Will you lead me down to the North Road?”

“Don’t you want to go through the village? Say good-bye?”

“Would you?”

“No.”

“No. Just get me to the North Road. Once I have it beneath my feet, I’ll know where to go from there.”

Part One

The Dark Hours

Oh sweet children, my beloveds, time to go to bed.

Oh sweet children, heavy-lidded,

you are bathed and you are fed.

Time for pillows, time for sleeping,

and fearless dreams to fill your heads.

Oh sweet children, my beloved,

time to go to bed.

Chapter 1

Toward Twilight

CANDY’S GANG OF ABARATIAN friends had plenty of plans laid to celebrate her safe return to the islands after the violence and insanity of the Hereafter. But they had barely finished welcoming her home with kisses and laughter (to which the John Brothers added an a cappella version of an old Abaratian standard) when Deaux-Deaux the sea-skipper, who had been the first friend Candy had made in Abaratian waters, came to find her, to tell her that word was being passed by every means in every direction, demanding her presence at The Great Head of the Yebba Dim Day. An emergency meeting of the Council of the Hours was presently assembling there to fully analyze the calamitous events that had taken place in Chickentown. Given that Candy had a unique perspective on those events, it was vital that she attend to give evidence.

It wouldn’t be an easy meeting, she knew. No doubt, the Council suspected that she was the cause of the events that had wrought so much destruction. They would want her to give them a full account of why and how she had come to make herself such powerful enemies as Mater Motley and her grandson, Christopher Carrion: enemies with the power to override the seal the Council had put on the Abarat and force the waters of the Izabella to do their bidding, causing it to form a wave powerful enough to wash over the threshold between worlds, and to fill Chickentown’s streets.

She quickly said her good-byes to those she’d only recently greeted again—Finnegan Hob, Two-Toed Tom, the John Brothers, Geneva—and with her geshrat friend Malingo for company she boarded the small boat the Council had sent and departed for the Straits of Dusk.

The journey was long, but went without incident. This was no thanks to the temperament of the Izabella, which was much stirred up, and carried on her tide plentiful evidence of the journey her waters had recently taken across the border between worlds. There were keepsakes from Chickentown floating everywhere: plastic toys, plastic bottles, and plastic furniture, not to mention boxes of cereal and cans of beer, pages of gossip magazines and broken televisions. A street sign, drowned chickens, the contents of somebody’s fridge, leftovers bobbing by sealed in plastic: half a sandwich, some meat loaf, and a slice of cherry pie.

“Strange,” Candy said, watching it all float by. “It makes me hungry.”

“There’s plenty of fish,” said the Abaratian in Council uniform who was guiding their boat through this detritus.

“I don’t see fish,” Malingo said.

The man leaned over the side of the boat, and with startling speed, he reached down into the water and pulled out a fat fish, yellow dotted with spots of bright blue. He proffered the creature, all panic and color, to Malingo.

“There,” he said. “Eat! It’s a sanshee fish. Very good meat.”

“No thanks. Not raw.”

“Please yourself.” He offered it to Candy. “Lady?”

“I’m not hungry, thank you.”

“Mind . . . if I . . . ?”

“Go ahead.”

The man opened his mouth much wider than Candy had thought possible, revealing two impressive parades of pointed teeth. The fish, much to Candy’s surprise uttered a high-pitched squeal, which died the moment its devourer bit off its head. Candy didn’t want to look revolted by what was probably a perfectly natural thing for the pilot to have done so she went back to looking at the bizarre reminders of Chickentown as they floated by, until finally the little vessel brought them into the busy harbor of the Yebba Dim Day.

Chapter 2

The Council Speaks its Minds

CANDY HAD EXPECTED TO be called into the Council Chamber, questioned by the Councilors about what she’d seen and experienced and then released to go back to join her friends. But it became apparent as soon as she presented herself before the Council that not all of the eleven individuals gathered here thought that she was an innocent victim of the calamitous events that had caused so much destruction, and that some punishment needed to be agreed upon.

One of Candy’s accusers, a woman called Nyritta Maku, who came from Huffaker, was the first to present her opinion, and she did so without any sweetening.

“It’s very clear that for reasons known only to yourself,” she said, her blue-skinned skull bound so as to form a series of soft-boned sub-skulls of diminishing size that hung like a tail, “you came to the Abarat without invitation from anyone in this Chamber, intending to cause trouble. You quickly did so. You liberated a geshrat from the employ of an imprisoned wizard without any permission to do so. You roused the fury of Mater Motley. That in itself would be reason for a stiff sentence. But there’s worse. We have already heard testimony that you have the arrogance to believe you have some significant part to play in the future of our islands.”

“I didn’t come here deliberately if that’s what you’re saying.”

“Have you made any such claims?”

“This is an accident. Me being here.”

“Answer the question.”

“If I was to take a wild guess I’d say she’s trying to do that, Nyritta,” said the representative from the Nonce. It was a spiral of warm dappled light, in the midst of which flakes of poppy and white gold floated. “Just give her a chance to find the words.”

“Oh, you really like the lost ones, don’t you, Keemi.”

“I’m not lost,” Candy said. “I know my way around pretty well.”

“And why is that?” said a third Council member, her face an eight-eyed, four-petaled flower with a bright-throated mouth at its center. “Not only do you know your way around the islands, you also know a lot about the Abarataraba.”

“I’ve just heard stories here and there.”

“Stories!” said Yobias Thim, who had a row of candles around the brim of his hat. “You don’t learn to wield Feits and Wantons by hearing stories. I think what happened with Motley and Carrion and your knowledge of the Abarataraba are all part of the same suspicious business.”

“Let it be,” said Keemi. “We didn’t summon her here to Okizor to interrogate her about how she knows the Abarataraba.”

She glanced around at the Councilors, no two of whose physiognomies were alike. The representative from Orlando’s Cap had a brilliant coxcomb of scarlet and turquoise feathers, which were standing proud in his agitated state; while the face of Soma Plume’s representative, Helio Fatha, wavered as though he was gazing through a cloud of heat, and the dawning face of the Councilor from six a.m. was streaked with the promise of another day.

“Look, it’s true. I do know . . . things,” Candy admitted. “It started at the lighthouse, with me knowing how to summon the Izabella. I’m not saying I couldn’t do it, I could. I just don’t know how I did. Does it matter?”

“If this Council thinks it matters,” growled the stone visage from Efreet, “then it matters. And everything else should be of little consequence to you until the question has been satisfactorily answered.”

Candy nodded. “All right,” she said. “I’ll do my best. But it’s complicated.”

So saying, she began to tell them as best she could the parts that she did know, starting with the event from which everything else sprang: her birth, and the fact that just an hour or so before her mother got to the hospital on an empty, rain-lashed highway in the middle of nowhere, three women of the Fantomaya—Diamanda, Joephi and Mespa—had crossed the forbidden divide between the Abarat and the Hereafter looking for a hiding place for the soul of Princess Boa, whose murdered remains lay in the Nonce.

“They found my mother,” Candy said, “sitting, waiting for my dad to come back with gas for the truck . . .”

She paused, because there was a humming sound in her head, which was getting louder. It sounded as though her skull was filled with hundreds of agitated bees. She couldn’t think straight.

“They found my mother . . .” she said again, aware that her voice was slurring.

“Forget your mother for a moment,” said the representative from Ninnyhammer, a bipedal tarrie-cat called Jimothi Tarrie, who Candy had met before. “What do you know about the murder of Princess Boa?”

“Boa.”

“Yes.”

Huh. Boa.

“Quite . . . quite a lot,” Candy replied.

What she’d thought to be the voices of bees, was forming into syllables, the syllables into words, the words becoming sentences. There was somebody speaking in her head.

Don’t tell them anything, the voice said. They’re bureaucrats, all of them.

She knew the voice. She’d been hearing it all her life. She’d thought it was her voice. But just because the voice had been in her skull all her life didn’t make it hers. She said the other’s name without speaking it.

Princess Boa.

Yes, of course, the other woman said. Who else were you expecting?

“Jimothi Tarrie asked you a question,” Nyritta said.

“The death of the Princess . . .” Jimothi reminded her.

“Yes, I know,” Candy said.

Tell them nothing, Boa reiterated. Don’t let them intimidate you. They’ll use your words against you. Be very careful.

Candy was deeply unsettled by the presence of Boa’s voice—and especially unhappy that it should make itself audible to her now of all times—but she sensed that the advice she was being given was right. The Councilors were watching her with profound suspicion.

“. . . I heard bits of gossip,” she said to them. “But don’t really remember much . . .”

“But you’re here in the Abarat for a reason,” said Nyritta.

“Am I?” she countered.

“Well, don’t you know? You tell us. Are you?”

“I don’t . . . have any reason in my head, if that’s what you mean,” Candy said. “I think maybe I’m just here because I happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Nice work, Boa said. Now they don’t know what to think.

Boa’s assessment seemed right. There were a lot of frowns and puzzled looks around the Council table. But Candy wasn’t off the hook yet.

“Let’s change the subject,” Nyritta said.

“And go where?” Helio Fatha asked.

“What about Christopher Carrion?” Nyritta said to Candy. “You were somehow involved with him. Weren’t you?”

“Well, he tried to have me murdered, if you want to call that involvement.”

“No, no, no. Your enemy was Mater Motley. There was something else going on with Carrion. Admit it.”

“Like what?” Candy said.

She needed to lie now, Candy knew. The truth was that she was indeed aware of why Carrion had been drawn to her, but she wasn’t going to let the Councilors know about it. Not until she knew more herself. So she said it was a mystery to her. And a mystery, she didn’t neglect to remind them, that had almost cost her her life.

“Well, you survived to tell the tale,” Nyritta remarked, his voice dripping sarcasm.

“So why don’t you tell it, instead of meandering around explaining nothing at all?” Helio Fatha said.

“I’ve nothing to tell,” Candy replied.

“There are laws defending the Abarat from your kind, you know that, don’t you?”

“What will you do? Execute me?” Candy said. “Oh, don’t look so shocked. You’re not angels. Yes, you probably had good reason to protect yourselves from my kind. But no kind is perfect. Even Abaratians.”

Boa was right, Candy thought. They were a bunch of bullies. Just like her dad. Just like everyone else. And the more they bullied, the more she was determined not to give them any answers.

“I can’t help it whether you believe me or not. You can interrogate me all you like, but you’re just going to get the same answer. I don’t know anything!”

Helio Fatha snorted with contempt. “Ah, let her go!” he said. “This is a waste of time.”

“But she has powers, Fatha. She was seen wielding them.”

“So maybe she saw them in a book. Wasn’t she with that idiot Wolfswinkel for a time? Whatever she may have learned, she’ll forget it. Humankind can’t hold on to mystery.”

There was a long, irritated silence. Finally Candy said, “Can I go?”

“No,” said the stone-faced representative from Efreet. “We’re not finished with our questions.”

“Let the girl go, Zuprek,” Jimothi said.

“Neabas still has something to say,” the Efreetian replied.

“Get on with it.”

Neabas spoke like a snail edging along a knife. He looked like irridescent gossamer. “We all know she has some affection for the creature, though why that should be is incomprehensible. She’s plainly concealing a great deal from us. If I had my way I’d call in Yeddik Magash—”

“A torturer?” Jimothi said.

“No. He’s simply somebody who knew how to get the truth when, as now, it was being willfully withheld. But I don’t expect this Council to sanction such a choice. You’re all too soft. You’ll choose fur over stone, and in the end we’ll all suffer for it.”

“Do you actually have a question for the girl?” Yobias Thim asked wearily. “All my candles are down and I don’t have any others with me.”

“Yes, Thim. I have a question,” Zuprek said.