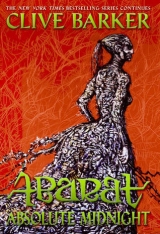

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Chapter 66

Love, Too Late

THERE HAD BEEN NO dissenting voice from anywhere throughout the glyph. The plan was simple: tell the ship where it was to go, and return with all possible speed to Scoriae.

“How?” said John Mischief.

“Good one,” said John Slop. “How?”

“Easy,” said Gaz. “We think.”

“We just have to think to make it obey?” Malingo said.

“I hope—”

Suddenly, the glyph responded to its creators’ instructions without a moment’s hesitation. It sped even deeper into the Void and then—when perhaps it sensed that it was so far from Scoriae that it was no longer visible, even to the keenest eye—it swung around.

“See?” Gazza said. “Here we go! I just hope wherever Candy is . . .”

“Do you think she knows we’re coming?” Malingo said.

“Yes,” Gazza said. “She knows.”

Events of great significance were happening out there, Candy knew. But what? She had to see.

“Window. Window. Window,” Candy said. “Carrion? I need to get to a window.”

It took a moment for the request to pierce Zephario’s anguish. Again, Candy had to say: “A window.”

“What about a window?”

“I have to find one.”

Zephario didn’t waste time with more questions. He reached out, open palmed, and touched the wall.

“I’ll wait with Christopher until she comes. You go, Candy. There’s nothing more you can do. Go on. I’m ready for her. It’s going to be quite a reunion.”

Even so, Candy paused. She wanted to be there when the Hag finally came face-to-face with the two men she had almost destroyed, but who had each survived, against all expectation. Candy, however, wasn’t here to watch. She was here to do some good.

“Go!” Zephario said. “I’ll find you again, somewhere. If not in this life, then in another.”

She didn’t like leaving him, but she knew she had to. She’d done what she could; now there was other work to do. Exactly what that work was she didn’t know, but her instincts told her it would all become clearer if she could just look out at the island. Perhaps they weren’t even over Scoriae any longer, but had drifted off out into the Void.

She got to the top of the next flight, and found herself surrounded by doors, all identical: gray, metallic, unmarked. She had no idea where she was in the vessel; all she had to rely upon was her instinct. It had served her well before and if she was lucky it would do so again. She just had to focus—

It was no sooner said than done. A door opened in front of her and she was running down a corridor, calling as she ran:

“Come on, windows. Come on! I’m here. Where are you?”

The corridor divided. Again she chose. Again she ran.

“Windows. Come on. Where are you?”

There were noises coming from all around her: through the walls, up from the metal gratings under her feet, and down from the tiled ceiling: shouts, roars, squeals, screams.

And thundering behind it all, the roar of the engines that fired up the storm on the legs of which the Stormwalker trod. She could run forever in this place, she knew, and never find—

Wait! A window! She sensed its presence like an open eye in the sealed brutal prism of this monstrous place. There was a door to her left. She opened it, moved through a passage to a second door, which again she opened. It brought her into a large chamber filled with what looked like suits of armor made for giants. She threaded her way between them, and came, finally, to the window. She was looking out into the Void.

Directly below her she could see the very edge of the Abarat: the limits of reality. Beyond that there was only Oblivion: a gray place that had neither depth nor detail, simply an unending nothingness.

“Must be a different window . . .” she murmured to herself. “Can’t be this. There’s nothing to see.”

She was about to turn when she realized her error. There was something out there in the nullity. And oh, Lordy Lou, it was coming at the Stormwalker at such speed, and so directly, that she had almost missed seeing it.

The glyph was coming out of the Void, set on a collision course with the Stormwalker. There would be no error in this. Her friends, no doubt assuming she was dead, were coming back to greet their executioners with a death blow of their own—

k

Mater Motley had seen her son through Carrion’s eyes, and had realized two things in the same moment: the first, that Zephario was now here in the sacred Temple of the Nephauree, and second, that the madness she had driven him into after the fire (some pitiful shreds of a mother’s love, incongruous though it was, had kept her from murdering him) had now been driven out of him. She knew without a moment’s thought whose handiwork this was: the witch from the Hereafter had touched him, damn her. It seemed every time Mater Motley encountered the girl she found another reason to despise her.

Well, no matter. It was all easily solved. Finally she would do what she should have done years ago: kill him. Nothing vicious. Just a quick execution to get him out of the way.The neatness of the solution pleased her. She was at the door, already thinking about how she was going to slaughter him, when she heard one of the stitchling Commanders say, “Empress?”

“Not now.”

“Empress.”

“I said NOT NOW!” her voice almost bestial this time.

She turned to reinforce her point, but her gaze never reached the Commander. Instead it went to the window, or rather the formless Oblivion beyond the window, and to the shape of a vast blade being flung out of that Oblivion.

At that moment, staring at the glyph as it hurtled toward her vessel, Mater Motley was given a helping of a kind of gruel she had not tasted since her childhood: helplessness.

“I hate you . . .” she said. “You and all the worlds.” But her hatred was not enough to stop the glyph. “They mean to strike us,” she said, her voice dead.

“Then it will break apart,” one of the Commanders said.

“You can’t break something that isn’t solid, you imbecile. It’s made of magic and hope. Damn her. Damn her.”

k

“Malingo? Gazza! I love you! Don’t do this! Can you hear me? It’s Candy! PLEASE SAY YOU CAN HEAR ME! STOP RIGHT NOW OR YOU’LL KILL YOURSELVES!”

“She said she loved me.”

“Who did?”

“Who’d you think, geshrat? Her! Candy! I heard her say she loved me.”

“I’M IN THE STORMWALKER!”

“She said—”

“She was in the Stormwalker. Yes, I heard her this time,” Malingo said.

“She’s alive!” Gazza said. “She’s in the Stormwalker and she’s alive!”

“But that’s terrible! She’ll be killed.”

“No. Not my Candy,” Gazza said, with unshakable confidence in the wisdom of his beloved. “She’s clever. She’ll think of something.”

In the Temple of the Nephauree, where Candy had left the father and the son, the great roar of the Stormwalker’s engines ceased the moment the vessel touched the Void. The temple was the wellspring for every bit of magic that kept the Stormwalker aloft, and for a few seconds the conditions of space itself—cold, silent, dead—took possession of the temple. Denied the air to feed their bright flames, the candles were instantly extinguished, every last light pinched out at the same instant.

Though both the silence and the darkness were utter, the two Carrions knew that something had entered the temple: something that even they, who lived lives steeped in nightmares, had no desire to see or hear. One of the Nephauree had crossed from its hiding place behind the stars and was here, in this place.

A primal terror clutched at father and son. Instantly, the sound of the engines came roaring back. But in the few seconds of its absence, its volume had risen by orders of magnitude. It wasn’t the sound of the vessel’s engines themselves that were so loud: it was the sound of the vessel itself. The Stormwalker was reverberating.

“The ship’s shaking, Gazza!” Malingo said.

“I don’t feel anything,” said Gazza.

“Not the glyph. The Stormwalker. Look at it. It’s rocking around. What’s she making it do?”

“Lordy Lou . . .” Gazza said. “I think we’re causing it. We’re pushing a piece of the Void in front of us—”

“How can an empty place have pieces?”

“Maybe it’s not empty at all. Like space isn’t really space. It’s full of stuff. Gas. Dust. Bits of—”

“Wait!” Malingo said. “Did you feel that? Now we’re shaking.”

“I think its trash from the Void,” Gazza said. “It’s breaking up against the ’Walker, and it’s flying right back at us!”

There was evidence that his theory was right. All but invisible energies were seething in the air ahead of the glyph. The garbage of Oblivion swept ahead of the glyph’s broom, breaking like a wave against the Stormwalker then thrown back at the glyph again.

“What happens now?” Malingo said.

“Your guess is as good as mine,” Gazza replied. “There’s no turning back. That I do know. In ten seconds we’re going to hit. And then—”

“We’re all going to die,” Candy said, her tone quite matter-of-fact.

She hadn’t moved from the window. Where was there left to go? She was looking over the Edge of the World, with Oblivion ahead of her, and with nothing behind except a world of melting stone. She was better off where she was, staring at the glyph that she’d helped bring into being. It was a freedom machine. It would strike the Hag’s Stormwalker so hard it would fling the death-machine back the way it had come.

In the Temple of the Nephauree, in the company of the unseen Other, Zephario Carrion held his son in his arms, quietly singing to him the “Lullaby of Luzaar Muru.”

“Coopanni panni,

Coopanni panni,

Luzaar Muru.

Copii juvasi

Athemun yezoo.

Coopanni panni

Coopanni panni

Luzaar—”

And then the two vessels struck.

Chapter 67

Yat Yut Yah

GAZZA’S THEORY—THAT THE DETRITUS of the Void, the trash of Oblivion, had somehow gathered up in front of the glyph as it speeded back toward Scoriae—was confirmed when the glyph hit the Stormwalker, pressing it closer to the gaping emptiness. The Empress’s vessel began to shudder, the motion minor at first but rapidly escalating, intensifying the assault of the detritus upon the Stormwalker. The ship’s dark armor cracked in places, and jagged pieces were torn away, their tumbling departure over the surface of the machine stripping away further pieces.

“Candy? Where are you? CANDY!” Gazza cried.

Gazza called out to her over and over, but now there was no answer. All he could do was watch the terrible spectacle of the machine in which she was trapped coming apart. It would not be destroyed quickly, he knew. The death-machine had been built, after all, to be a womb of storms. Not only to contain such birthing, but to channel their forces and to walk upon them. It would not succumb easily.

Even so, she was inside.

And she wasn’t answering him, even though he kept on calling.

“Candy? Candy? Candy?”

Standing at the window still, watching the collision, the Empress delayed going down to meet with the visitor she knew had entered the temple. The Nephauree were quickly offended; even now she should have been hurrying down to find out what this one wanted. But there was another piece of business more pressing still.

Candy Quackenbush.

The girl from Chickentown had been nothing at the beginning. Just a stupid adolescent who’d fallen off her world into the Izabella and been washed up on the shores of the Abarat. Insignificant, she’d thought; a nobody, who would somehow find her way to the Hereafter again, or would perish quickly in a world that she did not understand.

But she’d been mistaken. The girl was an enigma sealed up inside a conundrum with a tribe of puzzlements, nonsense and contradictions. And she had an uncanny knack for self-preservation, even when circumstances were not promising; even when Otto Houlihan, the Criss-Cross Man, one of the most successful assassins in the Abarat, had slipped and fallen before her.

There was no time for any more fumbled attempts. The girl simply had to die, now, in the chaos and confusion of this battle. Nobody would ever know how she’d died, or why. And as to who should do the job, she had no doubt about that. She would. Though she was an Empress now, and should have been above such squalid labor, she was the only person she trusted to do the job—the glyph, the state of her Stormwalker, even her guest in the temple—none of it mattered right now. All that mattered was to kill Candy Quackenbush. The girl was an abomination, a freak, and she would be dead within the hour. Only then, when she was looking down at the girl’s dead face—tasting her eyes and heart and liver—could she be certain that the First Empire of Midnight could begin.

The room where Candy had been standing, for reasons known only to those who had constructed the Stormwalker, was coming apart from both above and below, the metal panels of which the walls were constructed, buckling as though they were little more than pieces of tinfoil. Cracks spread across the window from left and right. Candy backed away from it, fearing it would shatter, and stumbled across the floor—which was collapsing in sections even as she crossed it—to the door. The door frame had cracked, however, and the door had been wedged closed. She wasted perhaps ten seconds trying to force it open before deciding that physical force wasn’t going to work. She was going to have to use the magical kind.

Many years before, her curious mind had plucked out of Boa’s private grimoire—for no other reason than that it was easy to remember—a wielding called the Cri Naz At. The spell was nine syllables, three of which were contained within its name.

Focusing her gaze upon the much-beaten door she recited them now.

“Cri Naz At

By Tu Hu

Yat

Yut

Yah.”

The syllables formed the image of a mallet in her head. Four syllables for its head, the other five forming its handle, which she held tight in her mind’s eye, her fingers wrapped around Tu Hu Yat Yut Yah.

The words slammed into the door, and a ragged crater four feet wide appeared in the metal. A shock of pain, all the sharper because it was completely unexpected, ran up through Candy’s hands and arms. This was something new completely: she was making a weapon with a spell, and literally wielding it. Now at least she understood what she was doing.

She gripped Yat Yut Yah even harder, and swung it with much greater force. This time, however, she was no innocent. She was entirely in the weapon—her thoughts, her news, her sinew, blood and bones. She was the bridge between the syllables and the force that it wielded. She was what turned words into action, into a force that would not be denied.

She slammed the syllables against the door

–Cri Naz At By Tu Hu Yat Yut Yah—

–and it flew apart!

Mater Motley heard the noise of the door breaking apart, but it would have meant nothing to her in the cacophony if it hadn’t been attached to a surge of power from the level below; a magical signature that she instantly recognized. The girl was right there, just a few walls away. She called out to her. If she knew that Quackenbush was close by, then surely the girl knew of her presence as well.

“I’m coming for you,” the Old Mother said.

In the Temple of the Nephauree, Christopher Carrion, ravaged by fear, whispered a flame into being. It was little more than a flicker, but it was enough to offer him a view of the ziggurat of extinguished candles.

“What are you doing?” Zephario murmured, his whispered voice carrying, despite the cacophony.

“I have to find the door.”

“You don’t want to see the Nephauree. Trust me.”

It was too late. The flame was already multiplying, leaping from wick to wick as it ascended the ziggurat, swelling to fill the temple with yellow-gold light.

From the corner of his eye—far off across the vastness of the temple—Christopher saw something no larger than a door that was opened just a crack onto a dark place. Then something that lived in that dark place threw the door open, and flowed through it, instantly swelling to become a vast incoherence, which possessed no sign of an anatomy whatsoever.

Gazing upon the Nephauree would certainly have been the death of him, but for the fact that at that very moment the blind man chose to act. He reached into his jacket, and seeing the iridescence that Zephario pulled out if it, the Nephauree unleashed a razor wire shriek that made blood pour from the blind man’s ears, nose and mouth.

It wanted what it saw in Zephario’s hand: a last fragment of the Abarataraba. And being the creature it was, it knew only one certain way to secure what it wanted. It would kill.

Sightless though he was, Zephario saw death.

Out of the Nephauree’s meaningless form came a horizontal flight of steel needles. The spears came within a hand’s length of Zephario’s skull, then they were casually deflected, blazing briefly in complaint, then flying out in all directions, dying as they fell. Even so, the Nephauree had not given up on the thought of capturing the errant shred of the Abarataraba. It unleashed another torrential shriek, which were orders of magnitude more distressing than the first. Zephario reeled away from its source though he knew he had no hope of outrunning it, nor indeed had any desire left in him to avoid his execution.

He had done all he could, made his farewells. He was ready for his trial by breath to be over, and in some place far from time and corporeality, have bright death finally begin.

With his back turned to his slaughterer he didn’t see the second descent of needle spears. And their piercing, when it came, was not as painful as the shriek of their maker had been. But the shriek was not silenced. It went on and on, his face streaming with fresh flows of blood from his eyes, like tears shed for the fact that he was not yet free. In his dying throes, he did the only thing he thought would make a difference: he sent the last fragments of his power to the girl, Candy Quackenbush.

“You’ve got nowhere left to go,” Mater Motley said.

Candy glanced back over her shoulder. The Empress of the Abarat was standing behind her, ten yards down the passageway. Everything was vibrating, much of it violently: the walls, the ceiling, the rivets in both. Only the Hag was still, uncannily still in fact, in perfect focus in a shaking world. Every detail of her dress was fixed, every doll hanging in there, each one of them a soul she had stolen, a prisoner: their suffering her constant pleasure.

“Yes is the answer,” Mater Motley told her.

“I didn’t ask a question,” Candy said.

“You were wondering whether I’m going to lock up your soul in one of my little dolls.” She smiled, showing her small gray teeth and mottled gums. “The answer is yes.”

Chapter 68

Deliverance

“GAZZA . . .” SAID MALINGO, SOUNDING slightly concerned.

“Yes, I know. The Stormwalker’s pushing back.”

At that moment the Stormwalker responded to the immense pressure it was under. Its violently vibrating form shifted a little to the left, and then turned at great speed. It shifted ninety degrees, its starboard flank suddenly facing the Void-cloud.

Presented with a larger target, the Void’s detritus threw itself forward with fresh insolence. The trash struck the Stormwalker, pushing it farther back.

“Oh, Lordy Lou! The Stormwalker’s moving again!”

This time there was no doubt that it was the pressure of the Void-cloud, not the Stormwalker’s engines, that was moving it. The death-ship moved suddenly and swiftly, turning a full hundred and eighty degrees as it flew, its massive engines laboring to regain some control, but without hope. The vast ship had too much momentum to be slowed.

The only thing that would stop it was the only thing that stood in its path: Mount Galigali.

“The volcano!” Gazza yelled. “It’s going to hit the volcano!” He was up now, trying to find his way out of the maze of the glyph. “We need to dissolve this thing. Now.”

Once again, everyone was in accord.

Barely taking his eyes off the vessel, Gazza stumbled out of the glyph. The vessel had behaved impeccably: carried its creators from their place of execution and into Oblivion itself, only to return them to Reality without losing a single passenger. But now the short epic of its life was over. Its energies were dissolving into the sulfur-stained air of Scoriae.

There were many among the disbanding seven thousand who took a moment to offer a prayer of thanks to the glyph in its dissolution. But neither Gazza nor Malingo were among them.

They, like Eddie, the John Brothers and Betty Thunder, had their eyes fixed on Galigali, which the Stormwalker was seconds from striking.

Mater Motley had been in the act of reaching to tear a hole in Candy’s body when the vessel lurched. But she still put self-

preservation above her desire to kill, and instead caught hold of a door frame to keep herself from being thrown to the floor.

Candy however lost her balance and fell, awkwardly and painfully, slamming her head against the wall on her way down. She tried to get up again, but the tumultuous motion of the vessel hadn’t ceased. The passageway was no longer solid; it shook so violently Candy’s eyes couldn’t fix upon anything long enough to focus.

Candy hadn’t realized how hard she’d hit her head until she tried to get up again. Her brain seemed too small for her skull, and her legs shook. When she reached out to touch the wall she found her fingers were completely numb.

“Not good,” she muttered.

She wasn’t the only one who’d lost control. So had the Stormwalker. It wasn’t just shaking and reeling, it was moving. And moving fast. She could feel its helpless speed, the way she’d felt in the car when her dad was drunk and driving like a madman, and all she wanted to do was close her eyes. It was that terrible memory—of her father—that made her defy her numb, weak body and get up. She was just in time. As Candy rose, Mater Motley reached for her a second time.

“No, Dad!”

The words came out so suddenly and so loud that the Hag paused for the briefest moment.

That was time enough. Zephario’s magic, finally reaching its destination, came up through the floor off to Candy’s right, and her first absurd thought was that somehow a bright bird had been trapped in the death-ship. The idea lasted a moment only. Then the colors melted into a single exquisite iridescence, and she felt lightness—in both senses of the word, of luminescence and of weight.

Candy saw Mater Motley’s iron hand reach into her body. But the vision was short-lived. Her gaze quickly went where her body had already gone, leaving the Hag to grasp vainly at the space where Candy’s body had been only moments before. Candy had only time enough left to see Motley’s rage: her gray-white face suffused getting paler still, while the black of her pupils spread to extinguish every last gleam of whiteness in her eyes.

She’d lost again. Candy was gone. Small though the fragment of the Abarataraba was, it was big enough to reverse the route that had carried her aboard the vessel in the first place, melting all that lay in the way of her escape: ceilings and floors, creatures and cargo, all parting like smoke when Candy approached.

The Abarataraba pulled her out of the vessel, and for ten, eleven, twelve seconds Candy was held in the air, suspended only a few feet clear of the Stormwalker’s speeding underbelly, as it continued to hurtle toward destruction. The ground was a jagged grid of lightning, discharged by the Stormwalker in a desperate attempt to slow the vessel down. If she landed in its midst, it would have been the death of her.

So the Abarataraba kept her in the air until the vessel had passed overhead completely. Only then did it guide her down to the ground. And now, as she looked back across Scoriae to the island’s northern shore (her sight sharpened by the power blazing in her cells), she saw a reason to smile. There was a large crowd of people—she knew it to be around seven thousand—all running in her direction, from the Edge of the World. Beyond them, the last remnants of the glyph were losing every last glimmer of solidity as its final passengers disembarked. It had done its work, and now dissipated, back to the ether from whence it had been borne.

The moment of calm was indeed brief, interrupted almost instantaneously by a din of destruction that shook the ground on which Candy was standing. She turned so quickly she had time to see the Stormwalker plow nose first into the crater where the peak of Mount Galigali had once been, now a ragged wound spitting fire and stone hundreds of feet into the air.

There the vessel came to rest. In a happier world all would have been put right. The evil-doers delivered into an all-consuming fire, and those who had been saved from execution free to return to their homes, lives and loved ones unharmed.

But this was not that happier world.

Chapter 69

For Every Knife, Five Hearts

INSIDE THE STORMWALKER, ZEPHARIO lay in the darkness and listened without fear to the steady slowing of his pulse. He was dying. Very soon his laboring heart would start to miss beats entirely, until finally, it ceased. There would be light then, and in that light he would see his family again, whose innocent souls had preceded him by many years into paradise. He had always imagined that place to be a garden—a garden where no flower ever withered, nor was any fruit corrupted by an invading worm. There his beloveds lived in bliss, beyond the reach of any hurt or harm. And he would be there with them soon. Very soon.

But even as he lay in the darkness, and the time of his deliverance from life drew closer, so too did the Nephauree. And it was not about to let him slip away into that peaceful place where his children played, at least not without one final violation. It prodded him with pushing until he rolled over onto his belly. He moaned. The slivers pressed against his back, but this time their intention was not to move him but to weave their substance into his cells, to press their presence into him, in four or five places.

He could not resist them. There was no strength left in him. What did this last cruelty matter, anyway? It would only quicken the approach of death to have his body invaded with such alien matter. Or so he had imagined. But no. The deeper the Nephauree’s matter invaded his flesh the more strongly his heart beat. And further from him the bright, beautiful image of the garden receded.

“No . . .” he murmured. “Let me go to them. Please I have no wish to live.”

“What you wish is of no importance to us,” the Nephauree replied. “We have need of you alive. So you will live.”

There was pressure exerted on him now, raising him up, his body’s weight causing him to sink back upon the spines, until they transfixed him completely, and emerged from his chest and abdomen. He was helpless, more puppet than self-willed being.

Thus, carrying him before it, the Nephauree departed the temple in search of worshippers, leaving Christopher Carrion in darkness.

Mater Motley could taste her own blood. She had caught her tongue between her teeth when the Stormwalker struck the volcano. But apart from that minor harm, she was unhurt. She got to her feet. The vessel was apparently lying on its side, because the closest she could find to a horizontal surface was what had been one of the walls of the passageway a few seconds before. She walked to the nearest door, sick with rage that the girl had once again slipped away. No matter. They were at the Edge of the World. There was nowhere now for the little witch to go.

The nearest door, she found, was above her. It was heavy, but it took only a flick of her will to tear it off its hinges. Then she spoke—

“Yet—

–ha—

–si—

–ha.”

–and ascended the smoke steps that formed in the air before her. What lay on the other side of the door was a spectacle of destruction so widespread that she might have taken pleasure in it had it not been her own Stormwalker that had been so demolished. She didn’t linger, however. There were noises that might have been death-moans of wounded giants coming from all directions, the last complaints of the vast machine as it sank into the melting pot of Mount Galigali’s crater.

There would be other death-machines in time, she knew. The Stormwalker had been but a hint of the glorious engines of destruction the Nephauree were capable of conceiving. She had seen some of them with her own eyes when she’d first ventured beyond the Starrish Door to find them, risking soul and sanity in doing so. But thinking of them now, of their power, and how many of their secrets they had shared with her, gave her weary limbs fresh strength. She climbed on, turning her back on the source of heat, and watching for a glimpse of the sky to appear through the smoke. There was cooler air coming from somewhere nearby. She followed it, her trek finally bringing her out of the carcass of the broken vessel and out onto the steep flank of Galigali.

She discovered that she was not alone. Dozens of stitchlings had escaped the conflagration, and were standing under the night sky, a sizeable number of them on fire, apparently indifferent to the flames. They certainly felt no pain. None of them even moaned.

She began to roughly assess their numbers, but it was a lost cause. They continued to emerge from every part of the wreckage, their will to live—even in the face of traumatic maimings—unquenchable. Many had horrendous wounds; some even crawled out of the Stormwalker without legs to bear them up. But though these gashes gave the Todo mud the opportunity to escape its confinement in these crudely sewn bodies, it seemed to be loyal to the form it had taken, to the individual each had become.

They clearly knew that they had their Empress in their midst, for when she emerged from the wreckage, they were waiting for her, standing around the lava pit, indifferent to the blistering heat. When she rose with the air above the wreckage, they let out a moan she had not known they were capable of making; a low note of celebration as though to lift her to Divinity.

“You good loyal soldiers,” she said. “You will have countless proofs of my love in return for this moment. I will lift you higher than any creature that calls itself alive, for you, though made of mud, are worthier.”

The stitchlings’ great moan rose up again.