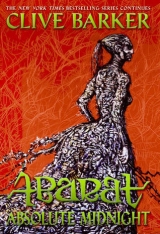

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“There’s a huge vessel—it’s a mile long, I swear—”

“The Stormwalker? Yes. I can see it on the screens in here.”

“It’s Mater Motley, Mr. Pixler. She is calling herself the Empress of All the Islands.”

Voorzangler heard the sound of live reports from the streets of Commexo City, which the great architect was presumably viewing. Pixler had built the city from the wealth the Commexo Kid had brought it. It was the work of a true visionary to have made a city of everlasting light at an Hour where the darkness was very deep. The city stood at Three in the Morning. But nobody who lived in its bright streets feared the night. Until now.

“You don’t care that this woman has a vessel capable of destroying the city—”

“She wouldn’t.”

“She’s perfectly capable of killing everything you—”

“And the Kid.”

“Yes.”

“Don’t forget the Kid.”

“But before the Kid was you, Mr. Pixler. You are the creator.”

“Am I . . . ?”

“Yes . . .” Voorzangler said, his voice a little less certain now, “. . . of course you are. Without you . . . There’s nothing.”

“The Kid?”

“Sir. You came before the Kid. The father must come before the son.”

“Yes . . .”

“So the city, sir.”

“Yes, the city . . .” He seemed to remember the words he’d once believed above all things.

“Commexo City belongs to the Spirit of the Kid and always will.”

“Good,” Voorzangler said, relieved that the genius he worked for had not lost his grip on the order of things. “So what do we do about the . . . Stormwalker, sir? It hangs above us with all its firepower directed at the city. You don’t want any harm to the Spirit of the Kid, surely.”

“Absolutely not. This city must stand as a testament to the dreams of the Commexo Kid.”

“Good, Mr. Pixler. So . . . What should I do?”

“What would you advise?”

“Me?”

“Yes, Doctor. What would you advise for the health of the Kid’s city?”

“I don’t think we have any choice, sir. We are either destroyed or we surrender.”

“Do you think if I were to surrender to this Empress person she might come for me here?”

“I’m sorry, sir. What are you saying?”

“I’m saying that if she wants total supremacy, then it would be quite a coup for her, would it not? My priceless body in return for the safety of the city.”

“Is that what you want to offer her, sir?”

“I accept,” Mater Motley said.

“Is that her?” Pixler asked, sounding quite puzzled.

“Yes, sir,” said Voorzangler. “It is.”

“How did she get onto our secure line?”

“She’s not on the line, sir. She’s here. With me.”

“What?”

“I’m sorry, sir, I had no choice.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“She forbade me, sir.”

“And like the sensible coward he is,” the Old Mother said, “he preferred to keep his one good eye rather than tell you the truth.”

“I don’t blame him,” Pixler said. “No doubt he thought his little life was all he had. So losing it meant more to him than it would have if he’d known the truth.”

“What are you babbling about, Pixler?” Mater Motley demanded.

“Once we witness the great certainties of the High Worlds and the Deep Worlds, once we know darkness absolute and breathe the truth of light, everything else—like life—seems inconsequential.”

“You make no sense.”

“Do I not? Well, the fault is surely mine, lady. I’m afraid I’m sick. Some strange contagion I picked up on my descent into the waters of the Izabella.”

“You’re not going to frighten me off with stories of deep-water plagues, Pixler. I fear nothing and no one.”

“Oh, Empress, that’s extraordinary! To have no fear. I want to look in your eyes and see that for myself. Voorzangler?”

“Sir?”

“Will you escort the Empress into the library?”

“Of course, sir.”

“I will be with you in just a moment, Empress.”

The line was broken and went to black noise.

“He’s no longer in contact,” Voorzangler said. “He’s never done that before. He’s always been listening.”

“Apparently not today, Doctor. Or he would have realized I was here with you. So take me to him.”

“I can only go as far as the door. I’ve never entered the sanctum. It’s his private world.”

“Well, today you will accompany me, Voorzangler. I am your Empress. Serve me, and I will always be with you.”

“Then of course I must obey you.”

Voorzangler proceeded to make his way through the poorly lit rooms. The only consistent illumination was from the hooded lamps above the paintings that lined the walls.

“Pixler has very eclectic taste, Voorzangler.”

“The paintings?”

Mater Motley paused to look at one of them: a very brightly colored canvas, depicting a simple white cottage, some trees, a small shed and a single star.

“Voorzangler?”

“Yes?”

“What is this atrocity?”

“I believe it’s called The Morning of Christ’s Nativity.”

“Decadence. Look at it, showing off its colors. It sickens me.”

“I’ll have it removed.”

“No need,” Mater Motley said.

She raised her hand and the canvas was consumed by an invisible flame, the bright color blackening and blistering until every last fleck of color had been consumed, leaving the antique gilded frame to enclose a view of almost any part of Abarat at that moment.

Just a few paces farther on was another picture, its style and subject as agitated and violent as the first image had been calm and peaceful. It appeared to be a body hung on a grid of barbed wire, but the details were hard to decipher. Again the cremating hand was raised, and Voorzangler flinched. But Mater Motley simply pointed.

“Now that,” she said, “I like.” She looked at Voorzangler. “All right. I’ve had my fill of art.”

She didn’t linger in front of any other painting, but followed Voorzangler to the large room at the end of the passageway.

“You seem to have a problem with your drains, Pixler,” she said as she stepped into the room.

“And with the lights . . .” Pixler replied from somewhere in the darkness. “Everything in here has failed, I’m afraid. Your . . . your . . . forces . . . Empress . . . have . . . taken . . . their . . . toll. My perfect city is no longer perfect.”

“Forget about your city. It’s you I need to see. Are there no lights in here at all?” There was an edge in her voice, more than a touch of suspicion. “Surely the chamber has a window, Doctor? The light from the burning city would—”

“Light . . .” Pixler replied, “would not . . . show you . . . anything your eyes would want to see.”

“You would forbid me?”

“No. Of course nnnnot. How could I? You are the Empressssss.”

“Then what’s going on in here? I demand to know.”

“If that is what the Empresssss wishes . . .”

“It is.”

“Then . . . sssseeeee.”

And suddenly there was light in the chamber, though it didn’t emanate from a lamp. It was Rojo Pixler, himself, who was the source of this frigid light, though his human anatomy was merely the frail centerpiece of a living form that had taken over the entire chamber, an intricate filigree of lacy tissue that covered the walls and hung in lazy decay from the ceiling. A foul stench was in these layers of rotting tissue, which here and there clotted, forming sluggish creatures that were attached by pulsing cords of matter to the body of Pixler himself.

Mater Motley seized hold of Voorzangler, her fingers digging so deep into his body that he cried out in pain.

“A crude trap, Doctor.”

“I had no knowledge of this, Empress,” Voorzangler said.

“She . . . is no Empress,” Pixler replied, his corrupted voice thick with contempt.

He rose up now, although there was little sign that it was the work of Pixler’s limbs that allowed him to do so. It was the creature within whose body he was enmeshed that drew him into a standing position.

“I . . . ammmmm . . . a part of something greater now,” Pixler said. “And I do not . . . ffffearr your DARKNESS, witch.” The light in the lace body flickered. “I . . . have passed eons in a deeperrrr darknesssss than your gray Midnight.”

Again, the light flickered. But it didn’t plunge the room into darkness. Instead it revealed, like a corrupted X-ray, the single vast anatomy of man and monster, exposing with appalling clarity how Pixler’s bones were interwoven with the stinking substance of his possessor. Rojo Pixler, the great architect himself, had become a piece of a piece of something that existed in all its unknowable immensity somewhere in the depths of the Sea of Izabella.

He rose up off the floor, lifted up on fans of fluttering tissue that shimmered as they worked. Rows of wet-rimmed valves twitched and spat; soft spines swelled into clusters of vicious barbs, surges of power passed through translucent ducts from one body to the next, noisily spilling Requiatic liquids onto the marble floor when they brimmed over.

“A Requiax,” Mater Motley said, her lip curling with contempt. “No wonder it stinks like a shore at high tide in here.”

“And . . . what is your stench, Hag?” the Pixler-Requiax said. By now Pixler’s body was ten feet off the ground, lit from below by the flashes of cold luminescence that spilled through the layers of tissue scattered everywhere.

“Tell your master to leash his tongue, Voorzangler, or else I will reach into that foul mouth of his and tear it out by the root.”

Voorzangler attempted to form some response to this, but she was killing him with her grip, and he was losing control of his body. His tongue could only flop about in his mouth, unable to shape a single coherent word. His whole anatomy had been drained of life force, and was now so weak that if the Empress hadn’t had her fingers buried deep in his shoulder he would have dropped to the ground and died where he fell.

But she held on to him, shaking him like a little one-eyed doll.

“Tell him, idiot!” All Voorzangler could do was shake his head in terrorized despair. “You thought to lure me into a trap, didn’t you? With this . . . fish.”

Again, Voorzangler shook his head, his control over his body seeming to become weaker with every passing moment.

“What do you want, fish?” the Old Mother said. “Are you hanging up there to terrorize me? Because you haven’t a hope of doing so! Whatever you assume you have made yourself, you are nothing, fish. Bow down! Do you hear me? Bow down before the Empress of the Abarat!”

As she spoke she let her free hand drop to her side, presenting her open palm to the floor. This simple gesture caused her to rise up into the air, dragging Dr. Voorzangler, his body now in the grip of something very close to a full seizure, with her.

Others had entered the room now, and were witnessing these grotesqueries: Voorzangler’s assistants from the Circular Room had followed him in, as had several seamstresses, but nobody made any attempt to intervene. This was a pitting of Higher Powers; everyone watching knew that. Anyone who attempted to interfere now would only earn themselves a quick death. So they all stayed close to the door in case things took a turn for the apocalyptic. And from there they bore witness.

“Bow down!” Mater Motley said again as she rose. “With your face to the ground.”

There was no response from the Pixler-Requiax, at least at first. Then, very slowly, the creature began to shake its head. The weight of the great architect’s brain distorted the soft bone as it swung back and forth, his mouth lolling open, allowing a stream of fluid that resembled molasses to pour forth. Its issue caused the stink in the chamber to become far, far worse: so vile and overpowering that three members of Voorzangler’s staff turned and fled, puking, back into the passageway.

But Mater Motley had seen and smelled far worse. She was untouched by this whole performance. She was standing on the air at the same height as the architect now and raising her hand, presenting her palm to the enemy.

“You have one last chance to bend to me. And then I will make you do so, even if I have to break every bone in you to do it. Choose, fish. Bow or be broken.”

The shaking of the head slowed, and then ceased. Pixler raised his own hand to wipe from around his mouth the last of the noisome fluid. When the thing spoke again the corruption of its speech was over. The Requiax spoke now with a clear intention to sound as though Pixler had regained control, enunciating each word with almost absurd precision.

“You would find it hard to break bones that are so soft—” the thing began. As it spoke, the thing lifted its arms above its head, seizing the wrist of his left with its right, and twisting it around as though the bones were made of rubber. “—I can let the currents carry me and never break.”

“So go back to your currents, fish.”

“I am no fish, woman,” the creature said. “I AM REQUIAX!”

Chapter 51

Father and Son

EVEN BEFORE THE FINAL syllable was out of the creature’s mouth it flung itself at Mater Motley. She had anticipated that it would do exactly that, because as it reached for her, something that resembled a fan, decorated in purple and gold, snapped open in front of her. She blew on it: the lightest of breaths, motes of purple and silver clouded the air around the Pixler-Requiax’s head.

Innocent though the weapon she had just called into service might have appeared, the innocence was a lie. It was that most guilty of things—a weapon possessed of the power to lay death down wherever its dart went. The purple and golden motes broke against Pixler-Requiax’s face like tiny sparks. As he threw back his pierced visage, finely knotted cords of dark matter flew up out of the many wounds and rose to strike the ceiling. Cobs of plaster came showering down, like brute snow. But their descent merely presaged a far more bizarre descent. The knots of dark matter burst like overripe fruit. Out of their split skins came a rain of the Requiax’s base matter; the raw sea muck from which its elaborate filigree was made. As soon as it fell on Mater Motley, it began to spread like a vine, insane with its own fecundity, coursing over her body in all directions; dozens of trails of the nameless stuff raced down her body, crisscrossing to form a foul-smelling net around her.

But it was her face that the Pixler-Requiax was most concerned to control, its matter wrapping itself around her skull from five or six directions at once.

“Idiot fish!” she said. “I’ve told you already. Why don’t you pay attention?”

She reached up and caught hold of the spreading networks of muck that had already overtaken two-thirds of her face. Her merest touch leached the color from the chaotic network of matter. Then she tore it, ripping it away from her face. There was more of the matter to replace it, of course, and the wrapping and tearing, wrapping and tearing struggle might have continued for a lot longer had a thin, shrill voice, that of a young boy, not said:

“Pops?”

Somewhere in the midst of the Requiax, the remains of Rojo Pixler woke from his nightmare of possession and saw—much to his horror—the only thing he had ever loved, the Kid, his Kid, at the threshold.

“Not now, son!” he yelled.

“What’s happening?”

“Nothing you need to know about. Now turn around and run!”

“Now what kind of cowardly lesson is that teaching the child?” Mater Motley said. She casually dropped Voorzangler, whose body was now inert, and reached out to the Kid. “Come here, Kid. I mean you no harm. Are you the last one standing?”

“No. I’m the First. The Original. The Kid of Kids.”

Pixler moaned to hear his own child condemning himself, but it was too late, the words were said.

“Oh, I think I need you in the Imperial Court, boy.”

“I can’t leave here, sorry. I gotta stay with Pops.”

“I’m afraid your poor father is lost forever.”

The copyrighted smile vanished from the Commexo Kid’s face.

“No,” he said softly. “My pops will live forever.”

“No. He won’t. Because your father has been taken over by something that found him in the deep trenches of the Izabella.”

“Don’t listen to it,” the Pixler-Requiax said. “She’s a liar. Always was. Always will be.”

Mater Motley raised her now-empty hand, proffering it to the boy.

“Come here,” she said, her voice all velvet and honey.

Her hands told a different story. The arm that reached for the Commexo Kid was becoming unnaturally long in its ambition to claim the child, its fingers also lengthening, their shadowy lengths sharpening into black points.

“Run, boy!”

“Pops! Help me!”

“Just go!”

The Kid started to race for the door. But Mater Motley’s hand snatched at his hair, her fingers growing longer, joints multiplying. The Kid lost his balance and fell backward, allowing the Empress to drag him back toward her as he shrieked for his father’s intervention.

“Stop her, Pops. She’s stealing me! POPS!”

It wasn’t his pops who replied, however. Or rather, it wasn’t simply his pops. It was the hybrid creature made of Rojo Pixler and the Requiax. And it wasn’t the Kid they spoke to. It was the woman.

“First you murder poor, stupid Voorzangler, who never did you the least harm. And now you go after my firstborn?”

The whole chamber shook, and the fractured marble on the floor split wider. Water started to pour up through it, its sharp, clean smell unmistakable. It was seawater that was bubbling up into Pixler’s stinking chamber, and it was coming up with such force that it threw over several more slabs of marble.

None of this distracted the Empress from her intentions. Her long-fingered hand closed over his face from which his trademark grin had vanished, and he screamed into her smothering palm.

“Don’t leave me with the bad woman, Pops!”

For those who had ventured over the threshold to watch this confrontation unfold, there was no choice now but to retreat and slam the door. It was either that or drown. The seawater was rising very rapidly in the chamber, the space itself repeatedly being battered furiously by the frenzied waters. The enemies fought with powers that invented some new crazed manifestation with every passing moment. Pieces of the bleached, dead matter fell away from Mater Motley’s face like shreds of a papier-mвchй mask, while new, mutated forms of the Requiax’s matter rose up behind the Empress’s head like a black wave curling and curling, preparing to break.

She was too interested in drawing the Kid toward her to even notice. Or perhaps she did notice and, in her supreme arrogance, was simply indifferent to the threat that the riding wave presented. Either way, she had her eyes and her attention fixed upon the Kid. Her arm, impossibly elongated, resembled a long, leafless branch more than a limb of flesh and blood. But there were no diminutions in its strength. With her hand still covering his face she lifted the Kid up, his thin legs with their cartoony shoes dragging through the seawater that was continuing to flood the room, the water rolling up against the walls, taking down the pictures that had hung there.

The waters were merciless with them, as they were with everything else that the room contained: the antique furniture, smashed to tinder; the walls themselves cracking as all that the room contained was caught up in the spiral of foaming waters.

The Kid had been pulled clear of the chaos, but Mater Motley knew that while she held the child—who was still shrieking for his father’s help behind her hand—the Pixler-Requiax could not act hastily against her. One slip, and Pixler’s firstborn went into the vortex. However tough Pixler’s manufacturing methods had made his child, once he was caught in the battering waters he would not long survive.

“Accept me,” she said. “Or the firstborn slips out of my hand.”

She raised her forefinger from the head of the child, leaving him held by only three spiked fingers and her thumb.

The Kid knew his life hung in the balance.

“Please don’t let her hurt me! Pops! Don’t! Let! Her—”

“He’s just a child,” Pixler said.

“He’s no child!” Mater Motley replied. “He’s painted plastic, or whatever you make these toys from.”

“He’s not a toy. He has a fully functioning brain. He’s able to feel love. And fear.”

“Oh, you mean these screams are the real thing?”

She lifted her middle finger from the Kid’s face.

“Don’t struggle, Kid,” Pixler said. “Just be very still. Please, my boy. Very, very—”

Before he could again say still, something burst from the tumultuous waters beneath the Kid. Another portion of the Requiax, formed from its matter in the likeness of a vast double-thumbed hand, rose up out of the water and seized hold of Pixler’s firstborn. The Kid’s shriek became so shrill now that no child born from a womb could possibly have made the sound. This was indeed the shrill shriek of a machine.

The sound momentarily was so sharp and sudden that it made the Empress lose her grip. The Requiax’s double-thumbed hand closed around the boy and quickly carried him away, still holding him up above the tumultuous waters.

“Open that door!” Pixler yelled, his voice—in its sudden, absolute clarity—unmistakably that of a man used to being obeyed.

And obeyed he was. The doors were opened instantly, the presence of the water in the room quickly subsided. The violent rush threw just about all those who’d been watching the confrontation off their feet, carrying them out into the passageway. There was still enough force in the water to give it the power to sweep the Crucifixion and Mater Motley’s “Midnight Nativity” off the walls, dumping them in the same scummy soup in which the witnesses were being thrown around.

From every direction came the din of terror and destruction, as the invading waters of the Izabella carried Voorzangler’s staff into the passageway, mercilessly tossing them about. The weakest of Mater Motley’s stitchlings were simply torn apart by the force of the currents, the rest carried away. The dead doctor’s staff shrieked and begged for mercy, but the waters granted no reprieves.

“Such noise!” Mater Motley complained with the offended airs of some highborn woman who’d never heard the din of suffering in her life. “Enough of this! Enough!” She threw a glance at the doors. “Shut up, both of you!”

The doors did as they were told. It was something of a struggle, but they pulled themselves shut against the power of the departing waters. Then, without further instruction, the forces the Empress had unleashed in the room set about melting the lock, which sent up a column of sulfurous smoke. The job was quickly done. The lock was melted, leaving the chamber sealed shut.

The Empress took a moment to compose herself. Then she said: “Let’s finish this business once and for all.”

Chapter 52

Atrocities

IF A STRANGER HAD wandered into the battle-scarred streets of Commexo City at about that time, they would surely not have been blamed for thinking they had taken a wrong turn somewhere, and found themselves in the clutches of a nightmare. Even though there were fires consuming many of the fine, fancy houses along the brightly lit boulevards, nobody was attempting to extinguish them. There were bodies sprawled on the streets and sidewalks, some apparently the citizens of this noble city, unarmed and dressed for anything but sudden death, killed by shrapnel or bullets and left to lie where they’d fallen.

There were sights even more terrible, that this wandering stranger would have found it difficult not to see, given how numerous such horrors were. And though they might have tried to look away, the scene and the tragic story it left half-told would be imprinted on their memory forever, so that even at life’s end, when they no longer knew their children from a tree, they would remember being in Commexo City with the death-ship filling the sky, and the buzzing of the innumerable flies.

Inside the Commexo Building, there was another scene, just as profound. The drowned lay where the draining waters had left them. The Empress’s seamstress attendants waited in the room, idly watching events unfold across the Abarat. The seamstresses were scarcely strangers to things fearful and abhorrent. They had been chosen by the Old Mother to accompany her into Commexo City because they had each in the course of their lives proved as unrepentantly vicious and enthusiastically cruel as she. Or at least very nearly so. But even they, who knew the bellies and bowels of the monstrous as well as heart and head, stood in mute awe and astonishment, seeing what atrocious glories their Empress’s Midnight had called up out of hiding.

Some of these scenes the seamstresses knew; they were the stuff of nursery horrors. Queen Inflixia Grueskin was one such: she was the monstrous Queen of Efreet according to legend, who tended her blood garden where for centuries she’d attempted to grow the missing anatomy to fill the empty cage of her body. She was a terror to frighten children no longer. She was real. There she was, up on one of the screens, in all her ghastly splendor.

On another screen, a tree called the Brakzee, which was by reputation the oldest in the archipelago, had become a gallows from which hundreds of ordinary people had been hanged. This was not the work of some vile demonic force. The executioners had been, until the disappearance of the moon and stars, the neighbors of those they’d hanged.

Nor was the incident at the Brakzee tree an isolated case. All across the islands fear caused ordinary people to do monstrous things. One of the seamstresses, going from screen to screen to screen, thinking each time she’d found the worst horror, but then discovering something still more atrocious said: “This is the End of Everything.”

It was Mater Motley who set her right.

“This is the end of their world. The purposeless ones who wanted only to live their lives. Their time is over. Midnight has begun. And out of their hiding places now come the Heirs of the Lightless Hour. See! They come to inherit this broken, bloody world and rule in my name.”

On screen after screen, beings that the women had never seen before appeared from their sanctuaries: monstrous creatures that had never appeared in any bestiary of the Hours, nor ever would. Now they had a world to rule by the laws of chaos. A slothful slug lay upon a slimy rock with a raw tongue-tail and hooks for hands; a two-legged beast with a quadruped beside it, walked through a place on Obadiah where a deluge of fire rain was falling; two human-headed birds sat on a dead branch, debating the weather—

Suddenly, from out of the sealed Chamber, the Empress’s command—

“To me! Women!”

A beat, then—

“NOW!”

The seamstresses had kept up a fine illusion of indifference for the benefit of Pixler’s storm troopers but they had been ready for this moment.

Now eight of them, acting as though governed by one mind, returned through the littered passageway, throwing their collective will at the sealed doors. The hardened sealant on the inside cracked, and the doors were flung wide, pushed from behind by the weight of the water. The women were ready for its fall. They threw up a quilt of invisible patches around them, sewn together by their own hands. It was only woven fabric, like any other, but such lattices have strength in their pattern out of all proportion to the mild stuff from which they are woven. The doors smashed against the quilt and broke.

The seamstresses entered the chamber and saw what the exchange between their Empress and the Pixler-Requiax had come to. The combatants were still high above the ragged hole in the floor through which the waters of the Izabella continued to surge up, their ambition unquelled. The Empress was elevated by a pillar of seething darkness, while the frail form of Rojo Pixler was borne up by the fronds of the Requiax’s continuously regenerating anatomy, which drew up with it countless lengths of woven water. Each carried, within its length, a cord of the Requiax’s matter, through which the desires of its mind were communicated. The mind had one desire above all others: to see the monstrous woman standing in darkness before it dead. She was the enemy—not the greatest of them, to be sure. Other evil, vaster than her by orders of magnitude, was using her to gain a stronghold here in Time. That would not happen! She had to be brought down. The glittering cords of the Pixler-Requiax went about their labors, wrapping themselves around the pedestal of shadows on which she stood, and then rising through the soul-laden folds of her garment, forming a net of knotted sea around her.

“Get! It! Off! Me!” the Empress shrieked, appalled by this violation.

She couldn’t get the rest of the words out. The water ropes had climbed her torso, and there was a noose of water around her neck. It tightened.

“No!” she said, and raised the hand she’d used to seize hold of Voorzangler, its fingers sharp and dark. Only this time it was onto her own flesh that she turned her piercing fingertips, sliding them down between her throat and the noose. She pulled the water rope off her gullet, far enough at least that she could get two words out.

“Free . . . . . . me . . . . . .”

The seamstresses were already raising their hands and speaking in old Abaratian the Eight Names of the Creatrix, which would summon to them the means to liberate their Empress.

“Giathakat.”

“Juth and Junntak.”

“Kiezazaflit.”

“Enothu and Eyjo.”

“Yeagothonine.”

“Yuut.”

“Yuut.”

“Yuut.”

Even before all eight had been spoken motes of fire ignited in their hands, forming vicious instruments, far more effective at cutting than any knife. They exchanged no words. They knew their business. They came at the column of darkness on which their lady stood and cut at the silver-green waters of Pixler and the Requiax. The tools that had been the gift of the Creatrix were as efficient as they were strange. They lacerated the waters, like assassins in a world of throats. Back and forth! Up and down! The cords of water, severed, fell back into the churning flood that had produced them.

Pixler-Requiax roared his disapproval.

“You should have stayed out of this battle, women,” he roared. “It’s going to be the death of you.”

The water was still pouring up out of the ground, weaving replacement ropes as it did so. They rose up suddenly—only two of them, but many times thicker than the cords that had climbed the column. They weren’t interested in disarming the women. It was the seamstresses themselves these two ropes of water were eager to claim.

The ropes did not linger to choose which women to take; they simply took, snatching two of the seamstresses from their cutting and summarily drowning them. The remaining seamstresses were too busy at their cutting to even notice that two of their number had gone. But the Empress did.