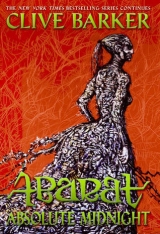

Текст книги "Abarat: Absolute Midnight"

Автор книги: Клайв Баркер

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“Now listen all. This Night is not yet lost. Look at them, down there! They are trapped. Oblivion is at their backs, Galigali’s fires at their front, and us in between.” She laughed. “Now, we are no longer eight thousand strong. So you will have to take four, maybe five hearts instead of just one. So, five hearts it shall be! March, my soldiers, march!”

A voice, far quieter, yet infinitely more disquieting than Mater Motley’s, spilled forth from within the wrecked vessel. It said only one word:

“Wait.”

Although Candy was at the very bottom of the slope of Galigali, she could, thanks to Zephario’s magic, plainly see and hear the events taking place at the volcano’s turbulent crest. The Nephauree was emerging from a tear in the side of the Stormwalker; it looked like a fluid stain spilling forth through the gaping hole. As it moved, the air it trod upon trembled; as it spread, it parted like two enormous pieces of torn smoke. And to her horror, Candy saw that the entity was carrying before it a living trophy, Zephario Carrion. He was wounded. Blood soaked the front of his robes. And yet as the Nephauree moved, Zephario continued to show faint signs of life. Despite all that his body had plainly endured, he was still alive.

The Nephauree emerged from the wreckage entirely, and Mater Motley bowed her head before it. The clotted, textured forms within the being responded by assembling at its core, their heads coming together in the midst of the alien’s amorphous stain, so that collectively they resembled a black sun, from which hundreds of frayed tentacles seemed to sway in the grip of the Nephauree’s abstracted energies.

Having paid her respects to the creature, Mater Motley turned from her ragged army—its numbers still swelling as more burning stitchlings appeared from the wreckage—and whispered one simple order to them. Candy heard the Old Hag’s imperative all too clearly.

“Kill everything.”

Chapter 70

Nothing But Stones

CANDY WATCHED THE BURNING, muddled army shambling down the slopes of Mount Galigali, with their Empress wearing her gown of souls leading, and the drifting form of the Nephauree both behind them and above, the nearly dead body of Zephario hanging in the shadowy air like a terrible trophy. Unsummoned, fragments of a song she’d heard first in Babilonium came to her head. A meaningless little nonsense, which she sang quietly to herself as she watched the army coming:

“I got a cold in my nose,

But it comes and it goes.

I got a cold in my brain,

Which nearly makes me insane.

I got a cold in my toe,

That I can’t get to go,

I got cold,

Cold,

Cold . . .”

And while the monsters came, she stood there, watching, knowing that she had no hope of stopping them. She looked back at the crowd that had emerged from the glyph, and saw that Malingo and Gazza had started to walk toward her. Gazza beckoned to her. She glanced one more time at the approaching enemy. They were still five minutes away, perhaps. But no more than that.

She turned and started to run toward Malingo and Gazza. Gazza was close enough to call to her now.

“Are you all right?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “I don’t think so.”

He opened his arms as he approached her, and hugged her tight. She gave as good as she got, which only made him hug her more. Malingo put his own arms around them both, which nobody objected to.

“What do we do now?” Malingo said.

“We have to defend ourselves,” Candy said. “We’ve no other choice.”

“I’m all for a good fight,” Gazza said, “but we don’t have a hope against those things. Look at them! They’re burning and they still keep coming. No legs, so they crawl.”

Candy looked back toward the volcano. The approach of the stitchlings was indeed terrifying. Though a few of the most traumatically wounded creatures had finally perished on the slope, the greater number continued their shambling descent.

“The Abarataraba’s all used up,” Candy said. “There’s still some magic in me, but there’ll be no more glyphs, I’m afraid.”

“What about getting off the island by water?”

“There’s no chance of that,” Malingo said. “Izabella just pours away over the Edge of the World. If we got into the water, we’d go with it.”

“There’s going to be a lot of killing,” Candy said grimly. “We have to make a stand here.”

“We were all brought here to die anyway,” Malingo reminded her. “At least this way we have a chance.”

There was another eruption from the heart of Galigali: this one so violent it blew the front half of the Stormwalker apart. It did not draw Mater Motley’s gaze off the condemned, however. She simply kept walking down over the smoking slope.

“I wonder what happened to Christopher?” Candy wondered aloud.

“He’s there,” Malingo said.

“I don’t see him.”

“I did, I swear. He was a little way back from all the rest, but he was there.”

Candy looked up at the approaching army with fresh interest.

“You’re sure?” she said.

“Absolutely.”

“Huh,” Candy said. “Three generations of Carrions.” She looked at Gazza and Malingo. “I guess we’ll go meet them together.”

Chapter 71

An Execution

CARRION HAD THROWN UP a low-resolution Distraction Shield to keep the stitchlings he was moving among from noticing him, but it scarcely mattered. They had their attentions entirely fixed upon those they were about to execute. So after a while he simply let the wielding lapse, knowing that they neither saw him nor would have cared if they had. It was only when Carrion realized that the girl from Chickentown had started to walk back toward his grandmother’s army—the expression on her face completely defying interpretation—that he repowered the shield and once again slipped out of sight.

In his invisible state he had a little time to get his thoughts in some kind of order. He no longer knew where his loyalties lay, or even whether there were any advantages to having loyalties. He had obeyed his grandmother’s instructions for many years, doing servile work much of the time, and what had that got him? Death and a bitter resurrection on a stony beach. And love? Ha, love! That had been even more cruel than loyalty. True, it hadn’t killed him. It might have been kinder if it had. Instead it had left him looking like a fool, having been tricked out of every piece of magic he’d ever learned and then left without so much as a kiss by way of compensation. He’d grieved. Oh, Lordy Lou, how he’d grieved. But more, he’d raged, the anger blazing about his heart, so that he’d had to stoop to murder in order to extinguish it.

But even that hadn’t been the end of the anguish. Fifteen years or so later, the girl from Chickentown had come into his life, their paths crossing by accident, or so he’d thought. She’d been washed into the arms of Mama Izabella, carrying—again by chance; again, so he’d thought—only to find that Candy Quackenbush of Chickentown, Minnesota, carried inside her the soul of the Princess whose manipulations and infidelities had left him stripped of power and love. Now Boa’s soul no longer occupied the girl, but it seemed not to matter. She still acted as though she could stand up against his grandmother! But she was wrong. This wasn’t the same Hag of Gorgossium any longer; the vicious old woman she’d faced on the Wormwood. The Empress was a different order of power. Why didn’t the girl understand that? Why didn’t she see with her own eyes the scale of his grandmother’s ally, the Nephauree? Didn’t she comprehend how incendiary a place this had become? Not because there was a volcano spitting air and earth around them, but because three generations of the Carrion dynasty were assembled for the first time since the fire that had wiped the future of that dynasty away, and returned all the power to the oldest surviving member of that family, in whose shadow he, the youngest, had been doomed to live?

Right now this was the most volatile place in the Abarat. And however much Candy might have learned about magic from Boa, she was still, at root, an ordinary creature of the Hereafter, strong of will, no question, perhaps even extraordinary in some regard. But she was still merely human, the shadowy places at the back of her mind still haunted by the beasts that had stalked the apes from which her kind had risen up. She would never be free of that fear, Carrion thought. And that would always leave her weak when facing Midnight.

And yet still she stood there, defying his grandmother, defying her own fear. Perhaps, just perhaps, she was something new. The next kind of woman, this girl.

Such a pity, if that was so, that she was going to die.

k

The two armies met. The Empress looked at Candy without any visible emotion.

“What do you want?” she said.

“I came because I saw Zephario in pain,” Candy said. “He’s your son. Doesn’t that make you a little merciful?”

“No, girl. I cleansed myself of mercy before I went to meet the Nephauree. I knew they would smell it upon me.”

“So you feel nothing for him?” Candy said.

She had no conscious notion of why she was even asking questions, but there was a reason, of that she was dimly certain. This was family business, and like all families the Carrions had their secrets. Whenever the members of her own family had got together, it had always ended with curses and fistfights. Perhaps there was some secret here that might yet change the way this fatal game ended.

“Oh, I do feel something for him,” Mater Motley admitted. “Something like maternal affection,” she went on. “Or as close as I could ever get.”

“Really?” Candy said. Now she was confused. What was the Old Mother admitting to?

“Yes, really,” the Hag replied. She reached down and caught hold of one of the ragged dolls that hung from the front of her dress. “I want his soul here,” she said. “Close to my heart.”

Candy said nothing. The Hag hadn’t finished, she sensed. So she still had something of significance to say. When she finally spoke, it was only to say five words:

“He won’t be alone there.”

That was it, Candy knew. That was the heart of it, in those words somewhere.

He won’t be alone.

The Hag had such a terrible malice in her face. Such a profound perversity. But why?

He won’t be—

Candy looked down at the doll, then back up at the Old Mother again, hoping to study the woman’s face a little while longer. But Mater Motley was already turning away from her so as to focus all her energies upon the broken figure of Zephario.

“Look at you; so old, so broken. I held you once, against my breast.” She began to walk back toward him. “Die now,” she said softly. “Give up your soul to me.”

She very slowly reached up toward him, as though she was capable of pulling his soul out of him. By way of response Zephario let out an anguished sound, something between a howl and a sob, the cry of a man losing his mind.

It was more than Candy could bear. She couldn’t just stand there and let the Hag go on tormenting him. She had to do something. What that something was she had not the remotest notion, but she had will, and she was free to use it. Whatever choices fate put in her head or heart or hands she’d use. Anything to stop the suffering.

She started to move toward the Hag, who was far too busy enjoying the anguish of her own flesh and blood to bother looking back over her shoulder.

“Stop that!” Motley said to her son. “It won’t do any good. I’m your mother, Zephario. I brought you into the world and now I’m going to remove you from it.”

Every despicable word of this quickened Candy’s step. She would do whatever she could to make the Hag regret her cruelty, she swore to herself. But that was more easily said than done, wasn’t it? Fate hadn’t provided her with any means to bring Mater Motley to her knees. She was up against the Empress of the Abarat with bare hands. But if that was how it had to be, that was how it had to be.

Without even thinking about what she was doing, she leaped, the very last traces of the Abarataraba’s magic lending her jump power it would never have had without it.

Without looking, the Hag turned, striking Candy with the back of her hand.

“Creeping up on me, girl?” She struck Candy a second time, and having nothing with which to shield herself from the blows, Candy was knocked to the ground, the breath beaten out of her. “I am so thoroughly sick of you,” she said, kicking Candy with unrestrained venom. “I’m going to kick you until your heart stops beating.”

She proceeded to make good on her promise.

“You.” She kicked.

“Stupid.” And again.

“Little.” And again.

“Nobody.”

“Stop it!” Malingo yelled.

Candy saw him from the corner of her eye, stumbling forward to put himself between Candy and the Hag’s assault. He distracted Mater Motley long enough to give Candy time to draw breath, but his intervention cost him dearly. The Empress cast a glance toward two of the stitchlings nearest to her and snatched the blades they were carrying out of their hands. Candy used the drawn breath to tell him:

“Run! Malingo! RUN!”

But even if he’d been willing to abandon Candy, which he wasn’t, his death sentence had been written. The blades came at him from left and right. Candy heard him cry out, just once, then the blades cut at him with horrible speed, slicing his head from his neck, his hands from his wrists, his arms from his torso—Candy’s horror and fury left her speechless, which was no bad thing. Not a scrap of her energies was wasted on words. All of it went straight from her heart to her hands. She reached up and grabbed hold of Mater Motley’s crowded skirts, hauling her aching body to its feet.

She had killed Malingo.

Her beloved Malingo, who had said he would be with Candy forever, Midnight or no Midnight. But the Hag had taken him from her. Snatched him away with a casual gesture, as though his life was worthless, his love was worthless, as though his body was no more than a slab of meat and she the butcher, casually cutting it up—

As she climbed, Candy found Mater Motley’s gaze, and for just a fraction of a second she saw the Hag recoil, her high regard for her Imperial Self shocked when it met such an intensity of hatred as it found pouring from Candy’s eyes.

It wasn’t enough, of course, to prick the Hag’s vanity.

She had killed Malingo.

No death was too terrible to revenge such a slaughter. Candy wanted to turn the Hag’s bones to blazing wood and her blood to gasoline, to watch the Old Mother consumed by the very element she’d used to kill her own flesh and blood all those years before. But she didn’t have sufficient magic to make such an execution happen. She’d have to do whatever damage she could do with her hands and fingers: gouge out the Old Mother’s vicious eyes and tear her lying tongue out by its rotting roots. She’d start with the eyes—

But the Hag wasn’t in the mood to die today. She reached up and caught hold of Candy’s hand, her grip so tight, and tightening still, that she plainly intended to grind Candy’s finger bones to dust.

With one hand holding Candy firmly, she reached out with the other. Her Imperial dignity was once again intact. And so was the power that accompanied it. She murmured a syllable or two, and one of the wide-bladed knives that had taken Malingo apart came to her outstretched hand. She closed her fingers around the sticky handle.

“I’ve had more than my fill of you, Miss Chickentown.”

So saying, the Empress raised the knife high above her head.

Candy refused to give the old woman the satisfaction of seeing her afraid. Instead she kept climbing, grabbing hold of whatever she could find, whether it was antiquated fabric of the dress or one of the dolls. Her bruises ached and her head throbbed, but not once did she take her eyes off Mater Motley’s turkey-neck throat, even as the knife came whistling down.

Chapter 72

Truth

THE KNIFE DIDN’T REACH her. Eighteen inches from Candy’s skin, it struck something: an object that was completely invisible yet sufficiently solid to shatter the blade as though it had been made of ice.

“Who did this?” Mater Motley demanded. “Who did this?” She glanced down at Candy. “It wasn’t you, so don’t even try to claim it was.” She thrust her hand over Candy’s face and pushed her away. Her presence here, dead or alive, was suddenly of no interest to her. Somebody here had blocked the Imperial will, and she wanted to know who.

She turned her black gaze on those in her immediate vicinity, staring very hard at each dirty, scorched stitchling for a moment to assess their chances of guilt.

“You, was it? No. Too stupid. You? No. Your brains are burning. You perhaps? No, another cretin. Is nobody proud enough to own this act?”

Silence.

“Are you all just mud and cowardice? EVERY? SINGLE? ONE?”

Finally, a weary voice said:

“All right, don’t give yourself a fit, you old boneyard. If it’s all that important to you . . . I did it.”

The crowd of stitchlings parted, a figure emerged from behind a flickering Distraction Shield.

“You,” the Hag said.

“Me,” said Christopher Carrion.

“Why must you always defy me?”

“Oh, Lordy Lou. I didn’t want you to kill the girl.”

“And again I say: why? You had a reason to protect her when she had your Princess in residence. But now?”

“I don’t know,” Carrion said. “But please, don’t . . .”

The Hag thought for a moment, then grinned.

“A favor for a favor, then?”

Carrion’s thin lips curled.

“What do you want from me?”

“Tell your father, Christopher,” Mater Motley said. “Tell him how he’ll be welcomed.”

Candy turned this phrase over and over in her head and watched Carrion’s face very closely. Her belief that there was indeed a mystery here, some family secret that was teetering on the rim of revelation, was deepening. She still had absolutely no idea of what it was. Her one clue was that the Hag had made that bizarre remark that after death her son would not be alone.

Was there somebody else held prisoner in Mater Motley’s dolls? Another soul—or souls, perhaps? Yes, it was several—she knew it the instant she thought it—and they were all being held prisoner in all those wretched little dolls made of filth and rags.

Suddenly, she understood.

“The children!” Candy said. “Oh God, she’s got all the children!”

Mater Motley didn’t respond at first. She had already moved with unnatural speed to stand in front of Zephario and had begun to sing a death lullaby to him. But Candy’s outburst silenced the slaughter song.

“Shut her up,” she ordered Carrion. “Quickly, you fool. Shut her up!”

“What’s she saying?”

“It doesn’t matter what she’s saying! Just SHUT HER UP!”

For a few seconds the Hag unglued her gaze from Zephario and threw Carrion a look, which briefly lit up his face with a burst of stinging, bitter green light, as though she’d just plunged his head in gangrenous waters. This was a new trick and it was only with the greatest effort that he succeeded in controlling his revulsion.

“Did you not hear me?” the Hag was saying.

“Yes,” Carrion said.

He didn’t need another lesson from his Empress. This newfound ability to render his own sanctuary poisonous was a terrifying escalation in her skills. He had no choice but to grovel. He stumbled toward Candy, his head roaring from the toxins still in his system, telling her as he did so: “You should have gone when I told you to. Now I have to kill you.”

“Have you heard a word I’ve said?” Candy asked.

“Not one more word!” Mater Motley instructed.

She’s afraid, Candy thought. I’ve got the truth!

The sudden certainty gave her voice power.

“Carrion, listen to me! She’s got your brothers and sisters!” Carrion looked at her through the strangely stained fluid in his collar with a look of puzzlement. “In the dolls. She’s got all your family right here with her.”

“SHUT HER UP!”

“Your father thinks they’re in paradise. It’s what kept him sane. But it was a lie, Christopher. Just another of her cruel, vicious lies. She’s had their souls all along.”

“In the dolls?” Now he started to understand.

“In the dolls.”

“And my mother too?”

“Don’t ask me. Ask—”

Carrion was already turning on his grandmother.

“Is it true?” he demanded. “Well, is it?”

“Haven’t you slit her throat yet?”

“I asked you a question.”

“You really want to know?”

“I asked, didn’t I?”

“Oh, you know me. I’m frugal. Nothing ever goes to waste. Not when it can be turned into power. I wasn’t going to let all those souls fly off to paradise when I could use them, here, close to me. They’re family, after all. My flesh and blood. They wouldn’t even have existed if I hadn’t endured the gross befoulments of the womb. I even let them sense one another, which does help them to hope. And they yearn, of course, for what they will never see again, never touch again, even though they’re so very close to one another.” She ran her bony fingers over the dolls as she spoke. “And the longer I keep them, the deeper the yearning gets.”

As Candy watched Carrion listening to this she thought she caught a glimpse of something she’d never seen in his eyes before. She’d seen him dangerous and despairing, loving and lost. But this, this was a singularity. Hatred.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” he said.

“What business was it—is it—of yours?”

“They’re my brothers and sisters.”

“You never knew them. Why should you care? You never cared before.”

“I thought they were in a happier place.”

“Well, who’s to say what they feel?”

“They feel everything . . .” Candy said.

“Shut up,” screeched the Hag.

“They feel everything—”

“I will—”

“—because they’re connected to everything.”

“—KILL YOU!”

“There’d be no power in them if they weren’t,” Candy continued, unmoved. “You only drain off what comes through them. But it comes from everything and everywhere.”

“The girl speaks the truth,” Zephario said very softly.

Candy glanced up at Carrion’s father, who was staring down at his son through his blind, bleeding eyes.

“Must I show you?” he said to Christopher softly.

There was no answer forthcoming from Carrion.

“Then I must.”

Strands of pale creamy mist were appearing in the fluid like a blindfold, concealing the innocent blue in his eyes as well as the nightmares, black at their center.

This had to be his father’s handiwork, Candy thought. Not that Carrion had resisted it. Zephario was showing his son a glimpse of the world they had both lost: of Carrion’s brothers and sisters, whose laughter, shrieks, tears and prayers he had many times imagined he’d heard.

“Your mother stayed in the house until the very end,” Zephario said. “I had to drag her out of there myself. That’s how I got the burns. I started to melt in the heat.”

“This is absurd,” the Empress muttered.

“You know it’s the truth, Mother,” said Zephario. “This is how it was, Christopher. Do you see? Do you see what your beloved grandmother did?”

Candy couldn’t, of course, share the vision, but she didn’t need to. She knew perfectly well what Carrion the Elder was sharing with the Younger: his mother, in extremis. Carrion had told Candy once that it was the first image he remembered, though at the time he’d no knowledge that it was his own mother he’d been watching die. She’d just been a screaming column of fire.

“I’ve seen enough, Father,” Carrion said.

Weakened by the visions, he blindly struggled to get to his feet, unable to see anything but the horror he was being shown.

“Father,” he said again, more violently this time. “Please. I’ve seen your memory now.” He got to his feet. “I believe you.”

And as he spoke the words, the clouds cleared away. Carrion’s eyes had never looked as blue as they did now, nor his pupils as black.

Chapter 73

Souls

OH, SO SLOWLY, CARRION raised his head. His purified gaze was fixed on Mater Motley.

“I see you now so clearly, Grandmother,” he said.

“The clarity of your eyesight is of no importance to me,” the Empress said.

“My brothers and sisters—”

“Are dead.”

“—should be in paradise.”

“Well, they’re not. Nor will they ever be. They’re part of the power that raised you so high.”

“Let them go.”

“No.”

“I can make you do it.”

“You could try,” the Empress said. “But it would be your last act.”

“So be it,” he said.

As he spoke he came at her, throwing some wielding ahead of him as he did so. It exploded in her face like a ball of spiked darkness. He didn’t give her so much as an instant to recover, but grabbed at her throat, apparently intent on throttling the life out of her. He carried her before him, stumbling back among her stitchlings.

Candy had seen the two of them meet head-to-head like this once before, on the deck of the Wormwood. She had no interest in watching the struggle play out again. Her concern was for poor Zephario. He was still pierced by the Nephauree, but he clung to life. She went to him. The temperature of the air dropped several degrees as she got closer to the Enemy of All Living Things: an unnatural chill that drove ice needles into her ligaments and marrow, making every step she took more difficult than the one before. But she would not be dissuaded.

Sensing her pain, Zephario raised his head. When he spoke his thoughts, it was a whisper of a whisper, the last exhausted murmur of a man using every sliver of strength to hold on to life.

The Abarataraba is still in you, he murmured.

I don’t feel it, Candy replied

It’s there. You would never have gotten so close without it. Not much of it, but—

What does it mean?

What does what mean?

Abarataraba.

. . . roughly translated, it means . . . Pieces of Life.

Then take them back. The Pieces of Life. Finish this. Set them free.

There’s a door in your head that Diamanda made when she put Boa’s soul into you. It’s not wood and hinges. It’s just a way into your being.

I know this door.

Then open it. Quickly.

I did it already.

Lordy Lou, so you did.

Will this hurt?

It won’t be my soul coming into you that will pain you, Zephario said, it will be my coming forth from you again.

Why?

Because I will enter you through a single door, which you opened. But if I am to free all the souls, I must exit through many.

You mean doors that haven’t been made yet.

I’m sure there’s a better way, but we don’t have the time—

Funny that. We live in islands of Hours and we never seem to have time enough for anything . . .

Here I come.

Instantly Candy felt the nerves in her head twitch. And Zephario’s life force came into her. It was strangely comforting, an odd sense of familiarity. Not the same as Boa being there, of course, but close enough. She felt Zephario’s anger turning her strength to its purpose, empowering her to face the monster.

The Hag had not even noticed her short exchange with Zephario. She’d been too busy fighting with her grandson. Unlike their battle on the deck of the Wormwood, in which the two of them had been equally matched, the balance had now plainly shifted in favor of the Hag. She had the wielding powers of the Nephauree at her disposal, and Carrion had nothing in his arsenal that was a match for them. Candy turned just in time to see Carrion drop down upon the ground, which was a chaotic mass of smoking fissures. The nightmares in his collar were writhing insanely, bleeding darkness into the fluid around his head. Whatever she had done to him, he had no fight left. The blow she landed would be the end of him.

“Empress?” Candy said. “I’m still here.”

Motley turned as she spoke. “Don’t worry, girl. My son’s dead, and my grandson’s almost gone. You’re next.”

Candy felt Zephario’s power moving through her as the Hag’s contemptuous gaze settled on her. The power divided as it did so: two becoming four, four becoming eight, eight becoming sixteen. He’d warned Candy it would hurt, and he’d not lied. The pieces of his divided soul coursed through her body in defiance of all anatomical constraints, burning their way like tiny fires through marrow and muscle, nerve and vein. Their passage was rapid, but before they could escape her, the Hag saw something in Candy that made her suspicious.

“What have you done?” she said.

She didn’t wait for an answer. She raised her hand, around which the air was already becoming denser as she summoned up a murdering spell. She would have let it fly a moment later had Carrion not caught hold of her arm. He lacked the strength to hold on to her for more than a few seconds, but that was all the time Zephario’s fragmented soul required to disperse itself throughout Candy’s body.

The instant he was spread, he burst free. The sting of his soul’s departure was almost more than Candy’s consciousness could endure. But she held on, despite the pain, and her anguish was rewarded with an extraordinary vision: the flight of soul-shards.

Seeing the motes speeding toward her, the Hag panicked. She wrestled her hand from Carrion’s grip and directed her murderous spell at the pieces of Zephario’s soul. But Zephario had outmaneuvered her. By dividing himself as he had into so many parts, he presented not one place to strike, but many. And while Mater Motley was still attempting to free herself, Zephario’s soul-pieces found what they’d traveled so far to find: his family.

As each of his children woke to the presence of their father, the filthy little doll in which its soul had been sewn up burst open as though a small explosion had been ignited in each. One by one, the dolls hanging in grim rows across the front of the Empress’s gown blew apart, as the son or daughter inside woke up to the proximity of Zephario.

Candy could not know, of course, what that moment felt like: soul liberating soul liberating soul. But she saw how it looked clearly enough, and it was no gentle business. Small though the dolls were they burst with astonishing violence, their coils of ragged cloth like entrails bursting from poorly sewn anatomies, as something both more abstracted and more real was set free.

If there was any way to distinguish one child from another, or the children from their mother, Candy couldn’t see it. They were simply points of brightness that burst from their squalid prisons, weaving around one another in front of the Hag as if to taunt her with their long-awaited freedom, then forming a cloud of ecstatic light that rose as its numbers swelled, the motion of the motes so fast that the trails they left upon the air seemed to form something that was almost a solid form: a ragged globe of threaded light, glorious in celebration of their reunion.