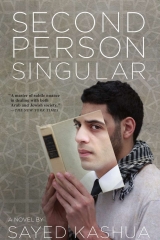

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

That night I hadn’t been able to feed Yonatan, or maybe it was as Ruchaleh said later at the hospital, that he refused to eat. He spit up the water substitute and his gelatinous meal, and when I came in to relieve Osnat, she said he had done the same with his breakfast and lunch. If this persists, she said, we’ll have to take him to the hospital, even though he doesn’t have a fever.

That night something changed in Yonatan. He reacted differently to our attempts to dress him, change him, moisturize him. Strange though it may sound to say about an irresponsive body, I felt that his skin had thickened and his bones and muscles had hardened.

When he didn’t ingest a thing during dinner, I told Ruchaleh that I didn’t think we should wait any more.

“He’s trying to kill himself,” Ruchaleh said later that night, in the waiting room outside the ER. That was the first time I saw her cry.

The doctors did blood tests, urine tests, a lung X-ray, and a CT scan and found nothing out of the ordinary.

“So he’s in good shape, then?” Ruchaleh quipped, but the Arab resident who’d given her the results didn’t laugh. “Arabs aren’t too strong on the sense of humor front, are they?” she asked me afterward.

In the small hours of the night Ruchaleh and I returned home. Yonatan remained in the hospital for a few more days, for observation.

On the way back Ruchaleh tried to sing along with the radio but she ended up just shaking her head back and forth.

“Are you sleeping at home?” she asked out of the blue, “or are you going to sleep over at that girl’s house?”

Her question shocked me because I had not told her or anyone else about the girl. “What girl? I don’t have a girl,” I said, and Ruchaleh smiled and again tried to sing along with the radio but she got hooked onto a different song, one that wasn’t playing, and all the way home she kept mumbling the lyrics, “Hug me hard, kiss me till it hurts, and the sun won’t set.”

When we got home, Ruchaleh said she needed a drink and she poured herself a glass of whiskey, neat, and drained it in a single gulp. Then she asked me if I wanted anything to drink.

“Yes,” I said, “but something else, if you have.” Up until that night the only alcohol I’d ever had was a beer now and again with Majdi, whenever he brought a bottle or two home, and red wine, occasionally, when he was given a bottle from the hotel as a Rosh Hashanah gift.

“I don’t have beer,” Ruchaleh said, taking a bottle of white wine out of the fridge. “White wine is usually chilled,” she said, and she showed me how to pull out the cork. Then she drank two glasses while I struggled with one.

“Do you even know how it happened?” she asked me, pouring herself another whiskey. I was silent and I think she interpreted that as a no. We’d never spoken about it. The accident,was how Osnat and I referred to it and that was all that Osnat knew. Yonatan had been in an accident.

“One fine day I came home and found him hanging from the ceiling,” she said, nodding her head and throwing back her whiskey. “I hugged his feet,” she said, demonstrating with her arms. “Then I got up on the bed. I grabbed his legs with one arm and tried to lift him with the other, putting all his weight on me as I tried to free his neck from the noose. Did you know that? Did you know that’s what Yonatan did to me?”

She took out a cigarette for herself and offered me one, too. I poured another glass of wine and watched the cigarette shake between her fingers.

“What do you say?” she said, trying to take the edge off the melancholy. “Would you do that to your mother?”

“No,” I said, smiling a bit for her benefit. “But I’d do it to myself.”

That was the first night I didn’t sleep up in the attic. Ruchaleh told me that she hated that room so much she could barely bring herself to walk into it, that she had an involuntary response upon entry, her eyes darting toward the ceiling, where there had been a light fixture, and where she found her son’s body, swaying in the air. He had been hospitalized in Israel for six months and was then flown to the United States, Belgium, and Switzerland. They – that is, Ruchaleh and Yakov, Yonatan’s father a professor of comparative literature at Berkeley – were never married, but they had lived together while Ruchaleh studied and, later, worked in Berkeley. When Yonatan was three, they split up and she came back to Israel. Yakov was all right, she said. Boring and a bastard, a long story, but nothing terrible. The truth is he really was all right, maybe, she couldn’t remember. Back when Yonatan was healthy, he would come visit them in Jerusalem twice a year, on Christmas and Passover, and would stay with them.

“This was his room,” Ruchaleh said, opening the door to the room that Osnat and I called the guest room, even though we’d never seen a guest. “You can sleep here tonight,” she said, and then pointed at the closet. “There are sheets on the top shelf and, by the way, I’d be happy if you made this your room. When you’re not with Yonatan, that is, on your days off from school or whatever. Instead of wandering around the streets like some homeless Arab you could just stay here. And do me a favor,” she said before leaving the room, “don’t get any big ideas in your head, okay? If you want to hang yourself, do it in your mother’s house in Jaljulia.”

THE FEEDING TUBE

Yonatan came home from the hospital with a feeding tube, a kind of straw that was anchored to the wall of his stomach on one end and dangled out of his right nostril on the other. Osnat gave me a brief tutorial and from that day on we started injecting his food into the tube. I learned how to extract the tube, how to clean it, and how to make sure it was not clogged. I’d shoot a syringe full of air into the tube and put a stethoscope to his stomach, listening for air bubbles.

Yonatan was in and out of the hospital over the next four years. He had infections of the intestines and the lungs, aspirational pneumonia, urinary tract infections, lung failures. Everything became more difficult. For some reason he also started to bleed whenever I shaved him, even with an electric shaver. I had the feeling that he didn’t want me touching him. It was around then that Osnat told me she was considering leaving and looking for a different job, one where she could be of more use. “Someplace a little less frustrating,” she said, and I asked her to please stay on a little longer, promised her that I would take care of all the more difficult tasks – the showers, the haircuts, the dressing and undressing and diaper changing – and that I’d do it all before she came in or after she went home.

“That doesn’t sound fair,” she said, but I insisted, explaining that Yonatan had become a friend, an ally, and that I would do anything to make sure that he did not have to part with a loving caretaker like herself, that I would do anything to ease him through his last days.

“Let’s make it clear to him that we’re not abandoning him,” I remember myself saying, and Osnat had no idea that what bothered me about the arrival of a new caretaker was that he or she might start asking questions about my relationship with Ruchaleh and with Yonatan, both of which had long since strayed beyond the ordinary.

The guest room became my room and I no longer slept up in the attic with Yonatan. After classes at Bezalel, I’d rush home by bus and relieve Osnat, who had started taking sociology classes at the Open University, mostly out of boredom.

“I feel completely unnecessary,” she said, even though, despite the terms of our unwritten agreement whereby I would do all of the hard chores, she continued to do most of the work herself.

As Yonatan’s body began to decay, it became more and more difficult to rotate him on the bed. Putting him on his stomach was never a good idea, certainly not without supervision, and once he was hooked up to the feeding tube it became downright impossible. He could no longer be placed on the special wheelchair for showers and so we began laying out rubber sheets and giving him sponge baths on the bed. Osnat, who had preached the importance of speaking positively around Yonatan and of playing him his favorite music and reading to him from his favorite books, now spoke openly about his dire situation. She stopped greeting him and parting with him each time she came and left the attic and instead spoke only with me, ignoring him entirely. I found her behavior embarrassing and usually after she left I would apologize to Yonatan, sometimes telling him outright and sometimes just letting him know with nothing more than a look.

Aside from the occasional evening when Ruchaleh would have friends over for dinner, the two of us ate together. At first she would come up to the attic and knock on the door and say she didn’t want to eat alone, but later she said she was sick of calling me to dinner like a little kid, and so I would come down on my own, unbidden, at the usual time.

“How’s it going in school?” she asked me over dinner, around a month into my first semester. I nodded in a way that was supposed to imply that everything was under control, even though I was pretty sure I would not be able to finish the semester. I discovered that there was a lot more to school than going to class. All the other students stayed late after class and used the darkrooms and the computer labs, and when I heard that at the end of the semester we were each supposed to present our work, I was sure that I would not make it to that point. Not only did I hardly have time to take pictures, I had no time to develop the film.

“It isn’t easy there, is it?” she said, wiping her mouth with a linen napkin and getting up, motioning for me to follow her.

“Here,” she said, pushing open the door to a small storage room in the basement. “I think the bulb might have burned out but it doesn’t matter. Yonatan used to buy regular bulbs and then color them red.” The light from the hall cut into the darkroom. Ruchaleh pulled a sheet off the top of an enlarger. “I think this thing still works,” she said. “Check it out. If it doesn’t, I’ll call someone to fix it.”

In the mornings, she drove me to school, since we were both going to Mount Scopus. We almost always left the house together. We waited for Osnat to arrive and then we left. If there was time we ate some breakfast at home and when there wasn’t we’d stop somewhere on the way and she’d tuck a fifty-shekel note into my hand and ask me to get two cups of coffee and a couple of croissants. Over time I learned that Ruchaleh did not always have to be on campus at Hebrew University as early as I did, nor did she have to leave as late. “What am I going to do at home?” she asked, and then said, “What, you think I’m a terrible mother?”

No, I did not think she was a terrible mother but I never said anything either way. She was not looking to be comforted, certainly not with words, and I was never sure what effect my words would have, anyway, whether they’d cheer her up or make her snap and accuse me of kissing up to the Jewish boss lady. Slowly I came to be convinced that what she believed was true: that Yonatan’s actions were a form of revenge. He never let up, as though trying to commit suicide each day anew, yet somehow surviving, just like the first time, in order to hurt her, to force her to remember. And ever since I started to use his identity officially, I felt he was doing the same to me, that this man, expiring slowly on his eggshell mattress, was acting rationally, premeditatedly. Sometimes, while we had dinner together or when she came into the darkroom to check out my negatives, during those moments of happiness, I’d feel as though Yonatan might at any minute come through the door, that that hollowed-out frame of a man might suddenly appear at the entrance to the darkroom and glare at us and say, “Just as I always suspected.”

But Yonatan did not get up or glare at us and his situation only worsened. He refused to live and he refused to die. The last time he was admitted to the hospital, around six months ago, was when I called an ambulance after checking his pulse and finding it unusually slow and weak. The ICU ambulance arrived immediately and hooked him up to a life-support machine. I rode with him in the ambulance and Ruchaleh followed in her car. That night a senior doctor who had been summoned to the hospital told us that it was unlikely that he would breathe again on his own.

“Some families, at this stage, decide to. .” he began to say, gingerly, but I cut him off, rejected the notion out of hand. My voice frightened me, the ferocity of it, and especially the notion that Yonatan might just disappear right in the middle of things and leave me all alone.

“I understand,” Ruchaleh said, after I apologized to her for my outburst, tears welling up in my eyes, “but I just can’t go on.”

She hugged me harder than usual and whispered in my ear, “You are going to have to decide.”

NUMBER 624

With a shaved head and a five o’clock shadow, wearing a long-sleeved Surfer Rosa T-shirt and green corduroy pants, the camera slung across my chest and round sunglasses on my face; with the old ID card, featuring a sixteen-year-old Yonatan, in my right pocket, and two new photos in my left – that is how I strode, back straight, mustering as much self-confidence as I could, toward the main branch of the Ministry of the Interior in downtown west Jerusalem.

I was in my fourth and final year at Bezalel, one of thirty photography majors. Nothing special. Nothing out of the ordinary. A classic Bezalel student, the kind the school was made for. I was Yonatan Forschmidt: Israeli, white, Ashkenazi, a consumer of Western culture. I was not Sephardic and I was not the token Arab.

Every class needed an Arab. In our freshman year we had the guy from Nazareth, but by our sophomore year he had been accepted at the architecture department and left. In the cafeteria we’d joke that we’d lost our Arab, and one kibbutznik from the Galilee said he’d heard that a class with no Arab was cursed and that we’d never succeed in the Israeli art world without one.

We were saved by the janitor from Silwan. According to the reports in the papers, the guy had been working at Bezalel for five years when the department head discovered him. It turned out that as soon as the guy was done washing the floor and scrubbing the toilets he would head straight for the darkroom, enlarging and developing the pictures he had taken with one of the department’s cameras. Apparently, he had made friends with the photography department’s storekeeper and had access to all the equipment he needed.

The discovery had occurred by accident: the head of the department had come back to the school late one evening and caught the Arab in the act, in his janitorial uniform, in the photo lab. At first the Arab had been terrified and had promised that he would never do it again, but the head of the department looked on in wonder at the drying photos that the Arab had taken in his village. The head of the department had offered him, right then and there, a spot in our class. The Arab said no, legend has it, because he had eight kids to support and couldn’t forgo his salary as a janitor. But the department head arranged it so that the Arab would get a full ride, would start as a sophomore, and would still receive his full salary in exchange for some minor cleanup work in the afternoon. Too bad I wasn’t born an Arab, the kibbutznik said, and everyone around the cafeteria table cracked up.

At Bezalel, I, a left-wing liberal like most of the students, learned that Arabs are horny, that they think with their dicks – mostly about pussy and mostly about preserving the honor of their sisters’ pussies. I learned that they can get angry fast and that there is no way to know what might set them off. They’re unpredictable and can be aggressive. Honor is desperately important to them; in fact, it’s all that matters to them – personal honor, national honor, religious honor, family honor. Show respect and avoid dishonoring them, and you’re on safe ground. Even the ones that seem the most enlightened are still, in some very basic ways, primitive. They think differently, have a different culture, a different logic. Arabs are more impulsive, more animalistic. The only thing they really understand is force, and when they sense weakness, they attack. Like hyenas. It does not mean that we should be occupying them, that is not what it means, but it’s such a shame that there’s no one you can talk to, such a shame that they don’t change, that they can’t really be trusted. Otherwise we could just sign a peace treaty, make a border, and make sure the two peoples stay friendly, each on their own side. If only they would just let up, let us live, be reasonable neighbors, get over their instinctive need for revenge, get over their obsession with honor, get over their mosque-fed fantasies of an Islamic empire. If only they could just admit that we were here first, that we are the natural owners of this land; if only they would just say thank you and finally understand how generous we have been.

Which is not to say that we don’t have our share of crazies. What about the nut-job settlers who are willing to risk the lives of their children in the name of some divine ideology. Or the ultra-Orthodox, and the Sephardim, who go on and on about ethnic discrimination. If they had any sense they’d come around and thank us for plucking them out of that dark and unenlightened place we found them in.

These things were said in the cafeteria or in the makeshift smoking corner, and they were said for white, cultured Israeli ears alone. The token Arab was always welcomed with open arms at Bezalel, with happiness even, and it never seemed artificial. Nor did the Arabs suffer. It seemed like our Arab enjoyed the whole thing. I think the Arabs felt very welcome at Bezalel and they were invited to virtually all of the events. A lot of girls threw themselves at them, and especially at our janitor, who, word was, could get any Jewish girl he wanted. In the cafeteria and the smoking corners, when we were alone, we, the founders, laughed at those girls and the way they used the Arab to get back at their parents. And we talked about the Arab phallus as art. I didn’t say much during those conversations but I laughed, got the joke. I was the quietest person in the class and no one knew that it was because I was afraid that my accent might emerge, even though I knew I sounded just like them, or very close to it. I knew that I had to stay focused at all times, making sure to maintain my crisp Ashkenazi Hebrew. Monk,is what the kibbutznik called me, also because I never talked about sex. I knew that there was talk in the department of me being gay or in the closet or, eventually, asexual. I picked up on those rumors while listening in on the Arabs’ conversations, who had no idea I understood everything they said. Lotimeans gay and adim achsas jinsimeans asexual. But I didn’t care. I wasn’t looking for a social life at Bezalel, even though on account of my ethnicity I had one without trying. During breaks and free periods I always found myself sitting with the coffee drinkers and smoking with the smokers. Still, though, other than my Saturday morning visits to Noa’s apartment, I had no social life to speak of. I didn’t go to any of the parties, mostly because they were at night, when I was busy with Yonatan, and I didn’t go to pubs or over to other people’s houses for dinner or to work on group projects.

I loved taking pictures and that is all I wanted to do. My show at the end of sophomore year focused on the kids who work at the Mahane Yehuda market, carrying supplies and cleaning up around the stalls. After that my professor called me “the social photographer,” a nickname that I took as a compliment, but many of the other students said that I was stuck, that I wasn’t trying to break through the formulaic doctrines of field photography and that I was scared to reach for something that might be more “artistic.” But the truth was that I had no desire to do that. People were all that I was interested in. Our year-end show was viewed by members of the faculty and either an artist, a curator, or an art reviewer. My grades and appraisals were some of the best in the class. With a little PR, as Noa said, I could have been one of the protégés, but I steered clear of the faculty. I never went to office hours, never confided in them about my photography-related dilemmas. I insisted on doing things my way, shooting only in black and white, and even though some of the teachers thought my insistence was a sort of handicap, I knew that my work was in no way impaired and that each project I did was better than the one that preceded it.

I always shot with the same film, ASA 400, with the same shutter speed and the same aperture. Aside from the assignments that required it, I never touched a digital camera and I never photoshopped any of my pictures. During the first two years of school, I used Yonatan’s Pentax 35mm exclusively, which was considered old-fashioned in comparison to the Canons and the Nikons that the rest of the kids had. And I always used a 50mm lens, no flash, no tripod.

For one of my assignments, the family portrait, I received consent and took pictures of kids and their parents in the center of the Beit Hakerem neighborhood on a Friday afternoon. I also took pictures of kids on their way to school and of a group of Romanian construction workers, who let me photograph them as they sat in the Old City on a Saturday and drank cheap beer. Another project, which got me the top marks in the class, was one I called “First Love,” in which I took pictures of girls on the phone, smiling and twirling their hair. Ruchaleh, who always looked over my work before I submitted it, also thought that one was the best. There were tears in her eyes when she looked at the girls.

“They’re all in love,” she had said, and that’s how the project got its name. The next day she went out and got me a new Hasselblad 6x6. “Yonatan always wanted a camera like this,” she said.

The old security guard at the entrance to the Ministry of the Interior on Shlomzion Hamalka Street asked me to open my bag and then sent me in with a jerk of his head. It was just after eight in the morning and most of the seats in the waiting room were empty. I went over to the wheel and took a number, 624. I looked up at the digital screen above the clerks’ heads, saw it said 617, and sat down at the far end of the back row.

“It’s like an organ donation,” is what Ruchaleh had said when she found out I was using Yonatan’s identity. I realized then that she had known about it for months.

“Why would I have a problem with it?” she said, shrugging. “Maybe the authorities have some issues, but it’s no harm done to me or my son.”

It took me a long time to understand Ruchaleh, or rather, to trust her. At first I thought it was really strange that my actions, which clearly constituted a crime, did not bother her in the least. How could a bereaved mother not care? Then I thought she might be after some kind of sexual quid pro quo, sex in exchange for silence. The poor weak Arab would fuck his way out of his situation and the forty-five-year-old woman would get to feel that she was setting him free while giving release to the passion that was burning inside him. A good deal for both parties involved. I realized soon enough that that was not the case, but I must admit that during those torrid days the thought of accepting such an offer crossed my mind more than once. Had I agreed, though, it would not have been in exchange for her silence or some type of monetary reward. It would have been because back then there really were times that I desired her.

I remember, for instance, the first time she asked me to join her for a movie at the cinema and dinner at Cielo, her favorite Italian restaurant in the city. Ruchaleh looked beautiful to me that evening – maybe because I saw her smile for the first time and maybe because I saw her cover a laugh with the back of her hand. I think she laughed after I asked her if she was doing all this for me because of her left-wing ideology.

“You know what,” she said, and a long while passed before she was able to stop laughing. “You Arabs really are idiots.”

That first time out to a restaurant was when Ruchaleh taught me how to lay my napkin on my lap while eating, how to keep my elbows off the table, how to dab at my mouth with a napkin, how to hold a glass of red wine and how to hold a glass of white wine, and how to handle the different cutlery.

“Your plate is not a rowboat,” she said when I angled my fork and knife against the sides of the plate, and she showed me how to position the cutlery when taking a break from eating and how to arrange it at the four o’clock position when I was through. “There are some things you just have to know,” she said, “if you want to be a part of the family.”

Ruchaleh’s family was from Germany. They hadn’t been through the Holocaust, she said, at least not her parents, who had the brains to immigrate to this stinking country in the early thirties. But she didn’t like talking about her parents, because “they’re not really your grandmother and grandfather.” I gathered from our conversations that she had nothing but scorn for tradition, nationalism, religion, roots, roots trips, and sentences like “He who has no past, has no future.” She believed that the Arabs did a bad job of impersonating the Zionists, who did a bad job of impersonating the European nationalists of the early twentieth century. Nor did she believe in identity, certainly not the local nationalistic version of it. She said that man was only smart if he was able to shed his identity.

“Skin color is a little hard to shed,” she said, “it’s true. But the DNA of your social class is even harder to get rid of.”

When I told her at first that I had no intention of applying to Bezalel under her son’s name, she laughed and said, “Why not? It’s like an organ donation. Around here identity is like one of the organs of the body and yours is faulty. You might as well admit it, being an Arab is not exactly the peak of human aspiration,” she said, laughing, and I could tell from the tone of her voice that she had not meant to offend me. “And what you have here,” she continued, “is an organ donation that could very well save your life.” I don’t think Ruchaleh was trying to convince me of anything then. She could already tell how badly I yearned for it. I think all she wanted to do was to make clear that if there was going to be any trouble, it would not be from her.

With a ding the digital screen flipped to number 624. I got up and walked toward the agent just as the bell sounded again and the screen jumped forward to number 625. A woman who had gotten up after me hurried over to the agent, racing me to the window, even though it was clear that she was cutting ahead of me. I was willing to give up my number, perhaps the whole procedure.

“Are you 624?” the agent asked me over the head of the other woman, who had already sat down in the chair and was saying, “But it already switched to 625.”

“Ma’am,” the agent said. “He’s ahead of you.”

“Doesn’t matter,” the woman one booth over said. “I’m free.” I sat down in front of her.

“How can I help you?” she asked.

“I’d like to update an old ID card,” I said, and I put Yonatan’s worn card on the counter.

“These days you can just do that in the mail, you know?”

“No, I didn’t know that,” I lied. Of course I knew—before coming to the ministry I’d found out everything there was to know about updating ID cards. I knew it could be done through the mail but I wanted to do it in person. I look like Yonatan, dress like Yonatan, and there was no way some clerk in the Interior Ministry was ever going to be suspicious of me, straight out of Beit Hakerem, in expensive clothes that were made to look cheap and a T-shirt with a picture of an obviously hip band she had never heard of. It was much safer than sending it in the mail. What I was afraid of was that the disparity between the two pictures, the wild-haired Yonatan and the short-haired shot of myself from the day before, would be too great to issue an ID card through the mail and that then I would be asked to come in to the ministry in person, already a suspect.

“Yonatan?” the clerk asked.

“Yes.”

“I was sure that you weren’t Israeli,” she said, paralyzing me.

“Why? Is something wrong?”

“There was no reason to be so nice to that lady,” she said under her breath, taking one of my passport photos and starting to fill out the details. “People here have no shame. Just say, ‘It’s my turn.’ What, you don’t know how to deal with people around here? Only force, that’s the only language they understand.”

On the way out of the office, with a temporary ID card under the name Yonatan Forschmidt in my pocket, I dropped a renewal application for Amir’s ID in the mailbox. Attached to the paperwork were two pictures of Yonatan that I had taken myself and touched up on the computer. Everything would stay the same, only the pictures were swapped.

I left the nationality line blank on Amir’s application, as many Arabs did now that it was no longer mandatory. This had to be done to prove that all citizens of Israel are equal, Arab and Jew alike, but once it went into effect, a new number code was introduced to all official ID documents and it told whoever needed to know the ethnicity of the card-holder. After all, names were not enough: Arabs and Jews sometimes had the same names – Amir, for example – and it had become trendy of late for Arabs to give their kids Jewish names, or “universal names” as they preferred to call them.

I was not worried about updating Amir’s ID via the mail. Swapping Yonatan’s picture for my own would not arouse anyone’s suspicion: even the lowliest clerk at the Ministry of the Interior knows that no one in this country wants to be an Arab.