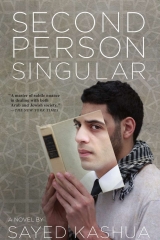

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Majdi was the master of the narghile. Like an artist at work he would shape the tobacco in his hands – the flavor of choice was usually apple – then he’d cover the tobacco with aluminum foil and punch strategic holes with a toothpick, laying the heated coals over the aluminum tent. He’d sit with the rubber hose in his hand and take monumental pulls from the water pipe. The king of nonsense, Wassim would say. The two of them passed the hose from mouth to mouth, exhaling long plumes of smoke toward the ceiling. I tried the pipe a few times, but I couldn’t really figure out what to do with the smoke once it was in my mouth. In the end I gave up trying, but still very much loved the narghile nights. Especially the tea, a weak brew with sharp mint leaves and tons of sugar – three teaspoons in each little glass.

On most narghile nights the main topic of conversation was girls. Majdi, who loved all kinds of girls, was full of stories about those he met at the hotel, at work, and on the bus. He liked talking about girls, especially the pretty Russian ones who worked with him at the hotel and the tourists who made eyes at him over their dinners. Wassim contended that he made it all up, that every single detail was false and that from what he could tell Majdi was on the fast track to becoming the most flagrantly lying lawyer in the country and that God should have mercy on his clients. Wassim, for his part, had a girlfriend. Or at least a sort of girlfriend. She was from their village, had studied education in school, and had gone back home after college. Wassim had never spent a minute alone with her, nor could he call her, because her parents or brother might answer the phone. But they loved each other, and it was clear that they would soon be engaged to be married.

“You’re missing out on life,” Majdi would say to him, “you should get the most out of the city before you lock yourself up in the village.” His advice, of course, was not heeded. Wassim was the exact kind of guy who would stay true to his love and marry the honest, shy girl from the village whom he had never so much as touched. “So long as her parents don’t give me too much grief,” he would say. “Her father is very rich. He has an electronic appliance store. And what am I? A teacher. .” Without a house in the village, there was no point in even discussing marriage. That was one of the reasons Wassim was still in Jerusalem. He wanted to save as much as he could before heading back home. That was also why every cent of the rent was painful for him to cough up. He managed to put away a salary and a half, but neither of them was substantial.

Majdi was more of a high roller. He earned a lot less than Wassim – interns got minimum wage – but he treated himself to new jeans and new shirts, and the money he did put away was earmarked for a new car. That was the other topic of conversation – cars. A BMW was the ultimate vehicle. It’s not the most expensive, Majdi would say, but it’s a beast on the road. In the meantime, he had his sights on a Volkswagen Golf, an ’84 or an ’85.

“Maybe you should get a second job,” Wassim said to me one night, the night that led me to Yonatan. “Maybe you should get a girl,” Majdi added, but Wassim ignored him. “There’s this one job,” he went on, “I don’t know if it’s still available but if it is, it would be perfect for you. The shifts are evening and nights, I think.” Wassim told me about Ayub, a teacher in his school who was about to get married and would have to give up the night shift. I remember Wassim saying, “You don’t have to do a thing, absolutely nothing. He takes care of a kid, in the kid’s house. The kid has some kind of problem, I’m not exactly sure what the technical name for it is, but if you want, I could ask Ayub tomorrow. All I know is that Ayub works nights and he doesn’t lift a finger. He says he sleeps better there than he does at home.”

“Okay, sounds good,” I said, not meaning it at all.

SCOUT

I waited for Ayub at exactly six p.m. at the bus station opposite Damascus Gate, just as Wassim had told me. Ayub showed up at six fifteen. I spotted him as he darted across the street that divides east from west. He was wearing a thick gray sweater and a heavy jean jacket that was lined with fake sheepskin. A backpack hung off one shoulder. “You’re the guy?” he asked before extending a hand. “Sorry I’m late. The road was backed up, some kind of accident or something, but don’t worry, we’ll make it on time.”

Ayub said that he usually took a share-taxi from Issawiya, where he lived, to Damascus Gate and that from there he walked down to Jaffa Road, some ten minutes away, and took the 27 bus or the 18, which went down Herzl Boulevard, leaving a short walk to Scout Street. But since it was really cold he suggested we take the bus to Jaffa Road. “I don’t mind walking,” I said, but Ayub said he didn’t want to be late, and just as he said that a bus nosed into the stop.

I got on ahead of him and bought two fares. The bus was practically empty. We sat toward the back and Ayub started telling me about himself and about the job. He said he was a special-ed teacher and that he had studied at the David Yellin College, which was no simple feat because he had a Jordanian matriculation certificate. “But I played it right, because I knew that the only thing I’d be able to do with a teaching degree from the West Bank was to wipe my ass, so I spent the year after college working on my Hebrew, then I took a prep course and got in to David Yellin. Of course, Birzeit and Bethlehem Universities are a thousand times better than David Yellin, but what’s a Jerusalem resident going to do with a degree from there? Everything here’s Israeli.”

When he decided he needed someone to take his night shift, he considered offering it to his cousins. They sat at home all day long and did nothing, but Wassim had recommended me really strongly, and Wassim’s a hard person to say no to. “Wassim’s a great guy,” he said. “He’s got a heart of gold. It’s hard to find people like him these days. Anyway, he told me a lot about you.” He also knew they wouldn’t take just anyone for the job. “They want a quality person, someone who knows Hebrew, too, and someone who has some kind of background. Someone who studied special-ed or nursing, but social work is good, too. It’s different, but it’s still about caring for others.” And anyway, he explained, there’s a registered nurse there all day long. “We’ll meet her in a second. She’s a good person, precise, goes by the books, but good. Her name’s Osnat.”

We got off the bus on Jaffa Road. Ayub waved me into a run as he sprinted toward the 27 bus, which was already at the stop. The bus was packed and there was nowhere to sit. There was barely anywhere to stand. Ayub, who up until then had been speaking in Arabic, switched to Hebrew – which he spoke with a heavy Hebron accent – and he did it naturally, as though it were the most obvious thing in the world. I didn’t know how to respond, in Hebrew or Arabic, so I held my silence. “The most important thing,” he said to me, “is to show her that you care about people. Be sympathetic. You know, interested. And don’t get freaked out when you see the kid. Just treat him like a normal person. He’s handicapped, but he’s still a person. His name’s Yonatan.”

Ayub told me that Yonatan was twenty-one or maybe, now that he thought about it, twenty-two, because more than a year had gone by since he started working there. Before that he’d worked at a home for mentally disabled adults, in addition to his job as a teacher. The home was where he met Osnat, the nurse, who came once a week to instruct the caregivers on how to treat the residents. The two of them got along well and one day she asked Ayub if he would be willing to take the night shift with Yonatan. “Working at the home was so different,” he said. “This job’s a breeze. You don’t have to do a thing. Yonatan sleeps through the night. All you have to do is rotate him a little bit every two hours. Turn him onto his back, his right side, his left side. That’s it. The rest of the time all you do is sleep, and no one cares. The mother’s out to lunch, doesn’t know what’s going on. Poor thing, she’s a good person, too. All she has is Yonatan. She lost her husband, not sure how, but he’s gone. Maybe she’s a widow or a divorcée, I’m not really sure what her story is. The best thing is not to ask. Why complicate things, that’s what I say.”

Ruchaleh, the mother, was some kind of doctor. Maybe of sociology. She worked up at Hebrew U and was a real lefty. So Osnat had told him. And Osnat, Ayub said, was also in favor of some kind of peace deal, which meant that the two of us should get along.

“We get off at the next stop,” he said all of a sudden, still in Hebrew, as he pushed the bell. When we stepped off the bus, he switched back to Arabic. “Remember this stop,” he said. “Right next to the pizzeria on Herzl. One minute from here and you’re at work.”

I followed Ayub down a small side street in the Beit Hakerem neighborhood. This is Scout Street, he said, then filled me in on more details about the job. “The shift starts at seven in the evening and ends at seven in the morning. It’s okay to sleep while on duty – there’s even a couch there for that purpose – but don’t say anything about it in the interview. Say you don’t plan on sleeping. Even though Osnat knows you will. She does, too. It’s fine. All you have to do is set your alarm for every two hours. I don’t even really need to wake up to rotate him. I just do it and go straight back to sleep. In the morning I’m refreshed, I sleep better than at home,” he said, laughing. He stopped outside one of the houses and pushed open a small gate. I followed him through a modest little garden. It was a stand-alone house, two stories. “Remember,” he said before sliding the key into the lock, “Scout Street, number thirty-five.”

JELLY

A week later I made my way to Beit Hakerem for my first night shift with Yonatan.

“I hope you’re always this early,” Osnat said, opening the door for me. She was alone, which is to say just she and Yonatan were home. I followed her down the hall and flicked a glance to the right, toward the book-filled living room. She led me up the narrow wooden stairs to the attic, where Yonatan lay.

“Hi, Yonatan,” Osnat said as we walked into the room. A strong smell hit me, the smell of unventilated air, medicine, and hospital food. “Look who’s here,” she said in a loud voice, as though the increase in volume would heighten his perception. “He’s going to spend the night with you, okay, Yonatan?”

Yonatan lay on his back. I looked at him, nodded in his direction, and offered a mute hello. I had spent two or three hours a day with him the week before, learning how to do the job, and I wasn’t sure if he recognized me or not, if he was even capable of such a thing. His eyes were open, fixed on the ceiling. I steered my eyes away from him, so it wouldn’t look like I was staring.

Osnat shouldered her bag. “Oh, I nearly forgot,” she said, walking over to what she called the staff closet, “there are sheets and blankets here for you. Everything’s been washed, so make yourself at home. Ruchaleh will probably be back soon and she knows it’s your first night. If you need anything, I’ll be home in half an hour and my home number’s on the board. Feel free to call till around midnight, okay? See you tomorrow morning at seven. Good night. Have a good shift.” She wrapped herself in a heavy wool coat, walked toward the door, and said, “’Bye, Yonatan, good night.” Then she left.

I heard the door slam shut below and immediately threw open the attic window. Shoving my head out, I breathed in the crisp air. Then I slid the window back along its track till it was just barely open. The radiator was working full steam and Yonatan was tucked under a blanket that had been pulled up to his chin.

He was positioned in the middle of the room, on a large bed, on what Osnat called an electric egg-carton mattress. It was connected to a machine that sent waves through the mattress, preventing bedsores. Bedsores—that was the word I heard most from Osnat, so much so that it seemed to me that my main goal at work was to keep them at bay.

There was nothing for me to do with Yonatan until eight, when I would feed him his dinner. The food was in a jar in a small refrigerator in the corner of the attic and once he had eaten it I was supposed to give him a small container of jelly, instead of water, which he couldn’t swallow.

I sat down on the recliner and stole a few glances at Yonatan, just to make sure that the blanket was rising and falling with the rhythm of his breathing. His wide eyes were fixed on the ceiling, his face expressionless. Osnat had said that Yonatan’s condition was defined as vegetative and that the cause was an accident. Ayub said it was a car accident, but he wasn’t 100 percent sure. I got up and looked for figures in the lit windows of the high-rises on Herzl Boule-

vard, thinking of how jealous I had always been of people who live in big buildings looking over crowded streets. They would never be bored, they could always just look out the window and see people. They’d never feel like they were alone.

A substantial amount of space had been set aside for Yonatan. The attic was built like a studio, with a large bathroom and a grand desk. There was an old computer monitor on the desk and shelves full of books above it. There was also a sleek and powerful-looking stereo. The speakers, on either side of the desk, faced the bed and alongside one of them were two tall racks of CDs.

I ran my eyes down the long column of discs and found that I did not know a single one of them. I’d never had a CD player. At my mother’s house and in the apartment in Beit Hanina we only used a tape deck and cassettes. I looked over the books and some of the titles seemed familiar, even though I’d never read any of them. The truth is that back then the only books I’d ever read were the young adult books my mother used to bring back from the school where she taught in Jaljulia. She talked a lot about how important it was to read, even though she never did it herself, and there were few books at home. At one point she bought me a set of encyclopedias – the school principal was a salesman – and I read from them pretty often. They, for instance, taught me about the reproductive system. I spent many a long hour in front of the strange genitalia illustrations, especially the female ones. I had read the chapter called “The Human Body” close to a million times.

I was sure that prior to the accident Yonatan had been a musician. There was a hard black guitar case in the room and a black box that looked like an amp. There were posters of what must have been his favorite bands up on the walls. One stretch of wall was decorated with framed photos, but they weren’t family pictures or anything like that, they were just photos, not always clear, sometimes shadowy and blurry, all in black and white. I thought to myself that it would have been interesting to hear him play, this Yonatan.

I was jealous of people who could play music. When I was a kid I really wanted to learn how to play an instrument, and for a while my wish came true. An engineer who lived in the village had gone to study in Russia and had come home with a music teacher for a wife. The engineer had not found work and his Russian wife, who was known in the village as Sweeta, started offering piano lessons to the kids in the village. My mother sent me to her house every Wednesday and for six months I had a weekly one-hour lesson. Sweeta was happy with my progress and said that if I wanted to continue to develop I had to have a piano at home. It could be a used one, she said, or an organ would be okay, too, but I had to have something to practice on. Mom went to Petach Tikva especially and bought me a battery-operated keyboard. When I brought it over to Sweeta’s house, she said that it wasn’t an instrument at all, that it was a toy. She showed me how it played nursery rhymes. And it only had eight keys, which was useless, because I needed to practice playing with two hands. That was my last lesson. I told my mother, who didn’t understand why I had given up the piano, that the teacher had said I wasn’t good enough.

LIQUID FOOD

I took the jar of food out of the fridge and placed it on the bedside table. Pressing the button, I raised Yonatan’s bed to what I thought was a suitable angle. His expression never wavered, and his stare, which had been set on the ceiling, was now leveled at the desk opposite his bed. I brought a chair over to the side of the bed and looked at the clock. In a minute it would be eight p.m.

The procedure sounded so simple and natural when Osnat explained it. But when I touched his inert body, a shiver went through me. Maybe it really would have been easier if I had spoken to him, as Osnat had recommended, but back then I was not able to relate to that thing at all. I wasn’t sure if he could even hear or see. While pulling down his blanket I tried to avoid all bodily contact. I stretched my arms to their full length, keeping my distance, and with unsteady hands tried to tuck the paper napkin into the neck of his pajamas. I felt the heat of his body and my hands jerked back as if I’d touched a poisonous snake.

“You can’t know what they know,” Osnat had told me. “You can’t know what he feels. But we have to be as humane as possible and treat him as though he were fully aware of everything around him. You shouldn’t mention his condition and you shouldn’t say things like ‘poor thing’ or ‘he’ll never get better.’” I reminded myself to act naturally and, inhaling through my mouth, I straightened the napkin under his chin.

I scooped up a flat teaspoon of the gelatinous purple food, just as Osnat had shown me, and tried putting the spoon into his mouth. Nothing. He did not open his mouth at all and I wound up smearing the food across his lips and down his chin. I took a napkin from the drawer and cleaned his face. Then I put some more food on the spoon and tried to pry his mouth open with my other hand, using a thumb and finger on either side of his jaw, feeling his teeth through his skin, but his mouth remained shut. I was scared that he’d suddenly open his mouth and clamp down on my fingers but I reminded myself that if he bit me it would be considered a medical miracle and that everyone would be glad.

Using a lot more strength than I had anticipated, I finally managed to open his mouth and guide the spoon inside, but nothing happened. The food stayed on the spoon. I turned it over in his mouth and shook the food off onto his tongue. “Slide it all the way back,” Osnat had said. There was no movement whatsoever, no sign of swallowing. I pried his mouth farther open and looked inside. Just as I had thought. All the food remained exactly where I had left it. Nothing had been swallowed. What do you do with this thing?

I knew this was not for me. I should have refused the job. But I hadn’t, and now I had no choice. I was alone and there were tasks that had to be done. I slid the long spoon back into his mouth and moved the food back toward his throat. With my other hand I raised his chin in the air, forcing his head back in a movement that reminded me of my grandmother and the way she used to feed her chicks. I wondered if something had gone wrong, if his situation had somehow changed since I had arrived. Otherwise Osnat and Ayub would have told me that feeding him is one of the most difficult chores. I tried my system again – squeeze open his mouth, insert the spoon, deposit the food, raise his chin – and then again. It wasn’t easy or fast, but it worked. When the food was consumed, I moved on to the water substitute, employing the same technique. By the time the meal was over I realized that I had touched him without so much as a second thought and that a full hour had passed.

I removed the napkin and wiped his face with two wet cloths. Then I used the button on his bed to return him to a prone position. That was it. All I had left to do was to rotate him every few hours and to watch him fall asleep. “He goes to sleep right after the meal,” Osnat had said, “and he stays asleep till morning.”

But Yonatan did not fall asleep. His eyes remained open and fixed on the ceiling. I decided to flip him onto his side. It wasn’t difficult: with one hand on his shoulder and another on his hip, I tugged once and he was on his side, staring me in the face. I should have flipped him the other way, I thought, so that I wouldn’t have that incomprehensible look staring me in the face. I could have moved my chair over to the other side of the bed, but that wouldn’t have looked good. You have to be mindful of his feelings, I reminded myself. I stayed put, doing whatever I could to avoid his gaze. Every once in a while I looked back at him to see whether his eyes were still open. They were, hauntingly so, but more than anything else they simply testified to the fact that he was not asleep.

A sharp smell filled the room. It was nothing like the unventilated, medicinal scent I had encountered when I first came up to the attic. No one had mentioned this to me. Not Osnat and definitely not Ayub, that son of a bitch. I went over to the window and opened it all the way, trying to overcome my nausea and cursing myself and Wassim and Ayub and Osnat. Yonatan, there was no longer any doubt, had defecated in his bed. I considered calling Osnat and telling her that I was very sorry but that I would be leaving right away. Instead I found myself on the phone apologizing for bothering her at this hour and asking all too politely how I should handle the situation. “It’s very simple,” she said. “You take off the diaper, clean him up with some wipes, and put on a new diaper. Strange, that almost never happens at night.”

I tried to work on autopilot. I marched over to the bed and pulled down his blanket. His body was surprisingly robust and athletic, considering, and he wore what looked like rather expensive pajamas. I decided on two things: I would get this done, and I would quit. This would be a one-time thing. I’d stay through till the end of this awful night and then go back to my life in Beit Hanina. At this hour, Majdi and Wassim were probably home. What I wouldn’t give to be with them.

The excrement had stained the waistband of his pajamas. Without thinking, I pulled his pajama pants down. It was worse than I had imagined. The excrement was smeared across his back and legs. I tried not to breathe. I flipped him on his back, undid the diaper tabs, and pulled. Then his bottom half was bare and for a moment I felt sorry for him, wondering if he could tell what I was doing and how it made him feel, if he felt anything at all. The situation was ghastly: most of his body and the bedding were covered in shit. Wipes were not going to be of any use. I remembered what Osnat had said about showering him, even though, as she put it, “this is hardly relevant because I give him a shower in the morning,” and I decided to put him in the special showering wheelchair, the one with the hole in the seat. I decided that there was no other way. A shower was what he needed.

I raised Yonatan’s head and tucked my arms under his armpits. He was far heavier than I had anticipated. My hands were wrapped across his chest. The special wheelchair was positioned alongside the bed. I pulled him as hard as I could and smeared shit all across the sheets. With considerable effort, I managed to get his uncooperative body into the wheelchair. According to the explanations I had received, this was all supposed to be relatively simple. He was to be placed in the chair and then tied in for support. Only there was no way to keep him steady and tie him in at the same time. Each time I took one hand off him he started to slide out of the chair.

You have to act as though you’re under fire, I told myself. I summoned every ounce of strength I had and in the end was able to press his heavy body into the chair and tie the straps around him. I took the sheets off the bed and threw them into the washing machine in the bathroom. Then I pushed the wheelchair into the bathroom and turned on the shower, waiting for it to get warm. What does this person, this thing, even know? If he felt anything at all, it must be hatred for me. Yonatan probably hates me more than anything else in the world, I thought. I’ll get this over with, deal with the rest of the night, and never see him again.

Later that night I wasn’t able to fall asleep. I lay down on the sofa, closed my eyes, and tried to think of soccer moves, a drill that usually put me to sleep. Instead I found myself practicing my conversation with Osnat, accusing her of lying about the nature of the job, and telling her that I would not be continuing. “By eight he’s usually asleep”. . Is that right? Well, why was he wide awake till midnight then? And yes, this was after I’d showered him, washed his hair, and wrestled him into his new diaper and pajamas.

In the morning I was supposed to take a shower myself, change clothes, and go straight to the office, “feeling fresh and well-rested,” as Ayub put it. I passed on the shower. It made me nauseous to think that I might have to stand naked and barefoot in the exact spot where the filth had poured off Yonatan the previous night. All thoughts of the previous night were revolting. I had washed my face, brushed my teeth, and used a towel from the staff closet, but I had been sorry that I had not brought my own.

Osnat arrived at five past seven. She had her own key.

“Good morning,” she whispered. Yonatan was still asleep.

“Good morning.”

“So, is everything all right? He seems to be sleeping nicely,” she said, yawning.

“Everything’s all right,” I heard myself say.

I took the undershirt, the T-shirt, and the pants I was supposed to wear that day and stashed them in the staff closet. I moved my toiletries kit there, too. “Have a good shift,” I told Osnat and hurried down the stairs. Why hadn’t I said anything? What am I going to do now? I thought. I was angry with myself and I felt my face flush.

Waiting at the bus stop on Herzl Boulevard, I imagined Wassim making coffee and hurrying Majdi out of bed. This was my first time leaving for work without them. Why the hell had I not said anything to Osnat? Maybe I’ll just disappear, I thought, without saying anything. What could possibly happen if I don’t show up tonight at seven? It would be a little awkward, and Osnat would definitely talk to Ayub, who would talk to Wassim, but all of that could easily be explained. I could also call her as soon as I got to the office and tell her that I would not be coming back. Some things have to be handled in that way. A clean cut. I decided that’s what I would do. So I’d lose a shirt and a pair of pants. It was a small price to pay.

The 23 bus was stuck at a red light before the stop. It didn’t run often but it was the best bus for me, as it went straight to the courthouse and from there it was just a two-minute walk to work. I counted the coins in my hand. I always tried to have exact change because I hated making the drivers do the extra work. A white car veered into the bus stop. I hated drivers who pulled in to bus stops.

“Excuse me,” I heard a voice call out. I swiveled my head. “I’m Ruchaleh, Yonatan’s mother. Where are you headed?”

I leaned forward and looked through the open window at the driver of the car.

“Wadi Joz.”

“Okay, get in, it’s on my way.”

I looked back one more time at the 23, which was pulling up to the stop, and then opened the car door and hurried in.

I made sure to look straight ahead and tried to breathe quietly.

“I’m headed to Mount Scopus. Wadi Joz is on my way,” she said in a tone that reminded me of her son’s expressionless stare.

“Thank you very much.”

“I saw you on the way down the stairs this morning. I was sitting in the kitchen.”

I nodded in silence and only then realized that there had been someone else in the house during that night of sleeplessness. At no point did I feel or hear her presence, there had been no shutting of doors and no footfalls. No sign of life at all.

“It was a rough night last night,” she said, and I wasn’t sure if she was asking or telling. “I came upstairs to say hi when I got home but I saw that you were busy with Yonatan in the shower and I didn’t want to bother you.”

I nodded bashfully. She had been there, and she knew what I had been through.

“I know this will sound strange to you,” she said, “but he was testing you last night. That’s why I didn’t get involved.”

I didn’t respond, and the two of us stayed silent. The roads were full of traffic and we moved along slowly from light to light. I looked over at the cars trapped beside us and tried to guess where they were all headed.

“Where do you need to go in Wadi Joz?” she asked when we reached Route 1.

“Right by the district court would be perfect,” I said, because I knew that it was on her way to the university and that most Jews didn’t like driving deep into Arab neighborhoods.

“That’s where you live?”

“No, that’s where I work, at the bureau of social services.”

“But that’s not near the courthouse,” she said.

“No, but it’s a two-minute walk from there.”

She drove past the courthouse, turned right, and then left into Wadi Joz, stopping right in front of the office.

“See you tonight,” she said, without a trace of a question mark.

MARLBORO LIGHT

Daud Abu-Ramila, my only active case, was waiting for me outside the office. He sat on the floor, hugging a big bag. “I’m clean today,” he said, adding with a laugh, “got the rehab started already.” This was the day I was to take him to the clinic in Lifta. He had already been through the committee, met all the requirements, and been told that the bed for the Arab residents was now available.

I punched in and made coffee for the two of us. He was excited, his movements sharp and quick. “I won’t let you down, you’ll see. I’m dying to get there already,” he said. “I’ll never forget what you did for me. Never. You saved me.” Once we’d finished our coffees, I called a cab and we prepared to head out to wait for the driver.