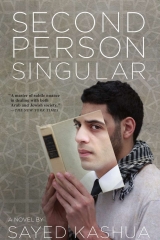

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

“Hello,” a middle-aged attendant said as he wiped his hands on a towel and walked out of his office. “Ninety-five unleaded?” he asked, and the lawyer nodded and said, “Yes, fill it up please.”

“How much does a car like this cost these days?” the attendant asked as he shoved the nozzle into the tank.

“Not sure,” the lawyer said. “A lot.”

“Great ride, though,” the attendant said. “You’re not from here, are you?”

“No,” the lawyer said, and he found himself adding, without much forethought, “Actually I came down here to look for an old friend from school. I haven’t seen him in six or seven years.”

“Who?” the attendant asked. “Someone from here? From Jaljulia?”

“Yeah,” the lawyer said. “His name’s Amir Lahab.”

“Lahab?” the attendant asked, screwing up his face. “You sure he’s from here? There’s no Lahab family in this village. Not that I know of.”

“No big deal,” the lawyer said. “Could be I got confused. I was just driving past and I thought of him. I might’ve gotten it wrong. Maybe he’s from somewhere else.”

“Baher!” the attendant yelled, turning his head toward the office.

“What?” a young man asked, coming out of the office and wiping his mouth with a napkin as he chewed.

“Is there someone named Lahab in this village? Is that what you said, Lahab?”

“Amir.”

“You know an Amir Lahab?” the old attendant asked just as the tank was filled.

“Ahh,” the young guy said, approaching the car. “Lahab? There’s that teacher, you know, the one from Tira, you know who I mean. .”

“Ah, yeah, yeah,” the older man said. “That’s her son he’s looking for?”

“Could be,” the young man said. “She had a kid in school. A few years older than me. He went to college. Could be him.”

The lawyer knew it was.

“What could someone like her ever do for someone like you?” the young man asked.

At that, the older attendant erupted. “Shut up and get out of here,” he hissed at the young man, then turned to the lawyer, afraid that somehow the young man had gotten them into trouble. “The kid is an idiot. I’m sorry. Don’t believe a word he says. I’m telling you, this village, may God forgive its inhabitants, they don’t let people live their own lives. I’m telling you that your friend was raised in a very good home. And if anyone in this village wants to tell you differently, then I’m telling you that he’s a liar and a son of a liar. No one will tell you that they ever saw that boy’s mother do anything wrong.”

“I’m sure. He was always a great kid,” the lawyer said, “that Amir.”

“What did I tell you?” the attendant said, shutting the gas tank. “Anyway, she rents from um-Bassem. Go up the hill,” the attendant said, pointing straight ahead, “and take a right by the Maccabi health clinic. There’s a sign with a Magen David on it, you’ll see it; anyway, take a right there. Go about a hundred yards more and ask for um-Bassem’s house.”

All the Arab villages look exactly the same, the lawyer thought to himself as he cruised through the streets. The local councils usually invest money on the entrance to the city and let the rest of the place rot, their main concern that there be a nice place for the head of the council to take his next campaign picture. All Arab villages have some kind of traffic circle near the entrance to the village and there’s always a pale-looking palm tree rooted there. The deeper into the village you go, the narrower the streets, until they turn to dirt, thin and dusty in summer and thick and oozing with mud in winter. The lawyer followed the gas attendant’s directions, driving slowly, attracting stares from the pedestrians. He stopped alongside a neighborhood convenience store. Two older men sat outside. He took off his sunglasses and opened the window. “ Salaam alaikum,” he said, playing up his country accent. The lawyer didn’t need their help but he figured he’d talk to them to quiet the neighbors’ unspoken apprehension and curiosity.

“ Alaikum a-salaam,” the two elderly men answered in unison.

“I am looking for the home of the hajaum-Bassem.”

“Um-Bassem, may Allah have mercy,” one of them answered. The lawyer tried to hide his embarrassment at the fact that he hadn’t known he was looking for a dead woman’s house.

“Take a right down there,” the second one said, pointing at the next turn. “The house is on that dirt road. Not the first, not the second, but the third house. That’s hers, Allah have mercy.”

“ Ta’ish,” the lawyer said, as though he were a family member accepting condolences.

The lawyer fished through his bag to make sure he still had the book. He’d introduce himself as a lawyer and say he was looking for the person to whom the note had been addressed. Or not. He imagined the man’s reaction and was rattled. It could be dangerous. And anyway how would he explain why he was looking for the man? The note didn’t even have Amir’s name on it. Maybe he should say he was a reporter, at least at first, until he had a better sense of the lover’s personality and could gauge how he might react. He could be a reporter who was working on a story about the outpatient clinic in east Jerusalem. Yeah, the lawyer thought, that was the way to go. He was a reporter looking into what seemed like years of corruption at the clinic. And if this Amir character didn’t buy it, then he’d just leave, no harm done.

“Who gave you my name?” he would certainly ask, and the lawyer would say he heard about him from a social worker by the name of Leila, and he would appraise the effect of her name on him. That’s exactly what he would do, he thought, and he parked the car past the house, out of view, because what kind of journalist drives around in a half-million-shekel car?

The lawyer knocked on the door and took a quick step back. A neighbor hanging laundry on a nearby roof eyed him suspiciously.

The door opened. A fifty-year-old woman looked at the stranger on her doorstep and then furtively at the neighbors.

“Hello,” the lawyer said.

“Welcome,” the woman said. “How can I help you?”

“Excuse me,” the lawyer said. “I was wondering if this was the home of Amir Lahab?”

“Yes,” the woman said. “Who are you? Did something happen to him?”

“No, no,” the lawyer said. “I just wanted to talk to him about something. Nothing major. I guess he’s not home, though.”

“No,” the woman said, her voice knotted with worry. “He’s not home.”

“I’m a friend of his,” the lawyer blurted out.

“A friend?”

“My name’s Mazen. I went to school with him. I was just in the area and was thinking of him and figured I’d swing by and see how he’s doing.”

“Oh, ahlan wa sahlan,” she said, looking relaxed. She stepped out of the house and closed the door behind her. “No,” she said to the lawyer, “my son, he’s not home, he’s in Jerusalem,” and the lawyer realized that he had not disappeared, as his wife had claimed, had not gone back home like most social workers who couldn’t afford to live in the big city on their measly salaries. No, he’d stayed in Jerusalem, for her.

“Do you have his phone number by any chance? We just kind of lost touch and. .”

“I wish,” the mother said. “I don’t have anything of the sort. Has it been a long time since you’ve seen him?”

“God, yeah, it’s been years. Since college, you know. How is he? Is he still working in the same field?”

“Yes,” the mother said, confiding in the lawyer. “He decided to stay there. I begged him to come home but he didn’t want to.”

“And you don’t have a number where you can reach him? How can that be?” the lawyer asked, chuckling, trying to make light of the situation.

“No, he doesn’t have a phone. There’s a line at work, so every once in a while, whenever he remembers his mother, he picks up the phone and calls me. Once a week, once every two weeks, he’ll do me a favor and ask me how I’m doing.”

“Well, you know how he is,” the lawyer said. “I miss him.”

“What can I say? I miss him more. But if he calls, I’ll tell him you came by. What did you say your name was?”

“Mazen,” the lawyer said. “Tell him Mazen, from the university, from the dorms.”

“I’ll tell him when he calls. It’s been over a month since he’s last been back to visit,” she said, visibly distraught, and she gestured for him to sit down at the plastic table outside, and the lawyer knew why she did not invite him in.

“So, has he gotten married? Wife? Kids?” the lawyer asked as he sat down across from the mother.

“I wish,” the mother moaned. “Nothing. Nothing. But you guys are to blame, his friends. Couldn’t you talk to him, find him a good girl. He doesn’t listen to a word I say. He’s almost thirty.”

“Yeah, wow,” the lawyer said, forcing himself to laugh, even though the thought of this bachelor, the man who danced with his wife at a party, made his blood boil.

“Are you also a social worker?” the mother asked.

“No,” the lawyer said distractedly. “I’m a lawyer.” And immediately he felt that he had made a mistake. One call to his mother and Amir would know that a lawyer whom he’d never met had pretended to be an old friend and one more call to the lawyer’s wife and she would already know exactly who it was that had been sniffing around Amir’s house.

“A lawyer? Amir has a lawyer friend and he doesn’t make use of him?” the mother said.

“Why,” the lawyer asked. “Is something wrong?”

“His inheritance,” she said. “He’s got ten dunamof land. Inheritance from his father. And he won’t even ask for it. You could easily get him his inheritance. I’ve already stopped telling him to demand what is legally his. Instead of wandering around and paying rent all over the place he could have sold his land and bought himself a house. It’s his, from his father. Why shouldn’t he take it?”

“Well,” the lawyer said, “I’m happy to help. Just tell him to call me. When do you think you’ll hear from him?”

“Huh,” the mother said, “probably not for another month. He took the trouble to talk to me yesterday. Gave me a whole half minute of his time. Said he was busy and then hung up. What can I get you to drink?”

“Thank you, I’m fine.” The lawyer hesitated for a second before asking permission to use the bathroom.

“Of course, no problem,” the mother said. She remained outside and gave him instructions for how to find the bathroom. “My house is your house,” she said.

The lawyer strode across the living room and already regretted asking to use the bathroom. He could easily have waited until he got back to the gas station. Head down, protecting the mother’s privacy, he walked straight to the bathroom. It was small and clean. The lawyer urinated and when he was done he remembered to put the seat back down. On his way out, he turned his head to the side for a second and saw what he was after, a picture of a young Amir. He felt a jolt of pain. The kid was handsome.

“I’m sorry,” the lawyer said as he walked back outside.

“What for, my son?” the woman asked, and the lawyer saw a light go out in her eyes when she said the word son. “On the contrary, I’m the one who’s sorry, for not being able to host you properly.”

“Thank you, Auntie,” the lawyer said, and he shook her hand. “Please tell Amir that I came by and was looking for him,” he added, raising his voice for the neighbor’s benefit. He handed the woman a piece of paper with a fictitious telephone number and left the house.

“A friend of Amir’s from Jerusalem,” he heard the mother yelling across to the neighbor.

A torrent of conflicting thoughts raced through the lawyer’s mind as he sat back down behind the wheel of his car. Why had his wife lied to him again? Why? He had so wanted to believe her, to help and defend her, to prove her innocence in the face of his own accusations. But how could he believe anything she said after this conversation with Amir’s mother? How was he supposed to believe that she hadn’t seen him since that night if Amir had stayed in Jerusalem and still worked as a social worker in the city? The lawyer knew that Arab social workers in Jerusalem were just like the lawyers – they all knew each other. Thanks to his wife, he even knew most of them.

On the way out of the village, the lawyer lit a cigarette and opened the car window. His phone beeped twice, alerting him to a message. He put the cigarette down in the car’s gold-colored ashtray. He hoped it was a message from his wife, but it was Samah, sending him Amir’s ID number. The lawyer pulled hard on the cigarette and expelled the smoke out the window. He did not like smoking in the car. It’s Saturday, and there’s no way for you to check his ID number, he reminded himself. Then he turned on the radio, searching for an upbeat song.

PART SIX. TRANSPORTER

“Yonatan?” the security guard half asked, half said as I got off the bus at Sirkin Junction near Petach Tikva. “Dude, you got to get yourself a new picture,” he said, looking at my ID card and then handing it back.

I walked toward the makeshift share-taxi stand that served the residents of Kfar Kassem and Jaljulia. As I arrived one of the taxis pulled out, leaving two Transporters in line. The two drivers, whose faces I recognized, sat on the curb and smoked.

Back in the day, all of the taxis were Mercedes-Benz sedans that could seat seven, but they don’t make those anymore, and since a regular four-door isn’t worth the drivers’ while, they now drive Volkswagen Transporter vans and never leave until they’re entirely full. On Thursday afternoons it’s never a problem because Petach Tikva is the hub for the villages of the southern Triangle.

I nodded at the drivers and had to mumble, “ Salaam alaikum.”

“ Alaikum a-salaam,” one of them said. “You can put your bag in the car.” He pointed to the van with the open door.

“Whose son is that?” I heard one of the drivers ask as I put my bag in the backseat.

“Don’t know,” the other one answered, and I felt their eyes on me. “Village’s gotten big, ah?”

I had to go down to Jaljulia. “Um-Bassem’s days are numbered,” my mother had blubbered over the phone the last time we talked. “It would be a disgrace if you didn’t come and say good-bye to her.”

The landlord, the one I called siti,or grandmother, her condition had been worsening throughout the year. She did not have any specific disease but she had lost her hearing and then her sight and her connection to the world around her had begun to deteriorate.

“I recognize your smell,” she said to me the last time I saw her, and her daughters were astonished that she could recognize me and not them or her grandchildren.

She kissed me, as always, and then said, “I saw you last night, you were with them, right? The soldiers. An army on horseback, planes in the sky. They flew right past my eyes.” She pointed ahead. “And I waved to them and said, may Allah be with you, may Allah be with you, and I gave them water and food.” Since then I had been back to the village twice and, despite my mother’s attempts to guilt and wheedle me into going, I had not been to see um-Bassem.

In less than ten minutes we had our seven passengers in the Transporter. Since all the rest of the passengers were women and kids, I sat next to the driver. I remembered that he who rode shotgun was, by convention, also the cashier. The ride from Petach Tikva to Jaljulia costs fifteen shekels and I started to collect the money and distribute the change. In the end I handed the driver ninety shekels in bills and coins.

“Who hasn’t paid yet?” the driver asked, looking in his rearview mirror toward the backseat.

“He’s a little kid,” an old woman in a colorful head scarf said, pointing to a child of four or so, apparently her grandson.

“Ma’am,” the driver said impatiently, “little, big, I don’t care. Is he sitting on a seat or not?”

“Fine,” she said, pulling the child toward her, “now he’s on my lap.”

“You see what I have to deal with,” the driver muttered in my direction. “That’s illegal, ma’am, the child needs to be strapped in. He can’t ride like that. You’re holding us all up and everyone’s in a rush.”

“But he’s just a child,” the woman said.

The driver cut the engine and folded his arms across his chest. “Really? Did you know that a child with no seatbelt is a one-thousand-shekel ticket? Where am I going to get one thousand shekels to pay the state of Israel? There’s a patrol car parked right at the entrance to the village.”

Slowly, so that no one but the driver saw, I slid two coins into the plastic ashtray. The driver looked at me, started the car, and mumbled, “ La hawal, wa la kuwa, ila b’Allah.” Neither by might, nor by strength, but by God. “These people, they come from their holes in the West Bank and they dump all their troubles on us, as if we didn’t have enough of our own. Ma’am, do me a favor, put the kid back in his seat and strap him in tight, okay?”

Oh, how I hated the drive from Petach Tikva to Jaljulia. The sharp smells filtered into my nostrils and spread through my entire body. The scent of bad and irrepressible memories. A scent that only intensified as we approached Jaljulia.

“You from the village?” I heard the driver ask, and when I realized he was talking to me I needed a moment to situate myself in my own life story.

“No,” I heard myself say, offering a different, but also true, version of my life. “I’m from Tira.”

“Ah, from Tira, great people,” the driver said quietly, a smile spreading across his face. “ Yáanione of us. I said to myself, he looks a little different, but he’s got a good face. I said to myself, no way he’s part of that garbage they’re always dumping on us from the Territories.”

“No,” I said, “I’m not from the Territories.”

“They dumped a lot of collaborators on Tira, too, no?”

“So I hear.”

“It’s just unbelievable. I’m telling you, they’ve destroyed our villages. These days a man has to worry about letting his kids out of the house after dark, all because of them. The guns, the drugs, the whores, it’s all them. And the police? Nothing. What do they care? As far as they’re concerned they can turn our villages into hell, they don’t care. Best I can tell it’s exactly what they want.”

“Yeah,” I said to the driver, who was looking in his rearview mirror to make sure that his words hadn’t been heard by the wrong pair of ears. “Do you have your ID with you?” he asked all of a sudden.

“What? Yes, why?” I asked, nervous, and the driver pointed ahead with his chin toward the traffic cop and the blinking light-stick he was flicking toward the side of the road. “Looking for illegals.”

“How you doing tonight?” the officer asked the driver through the window.

“ Walla,thank God,” the driver said, smiling. “As you see, working.”

The policeman looked the passengers over and, seeing that it was all women and children, turned to me and asked for my ID. I looked around in my bag and pulled out the right set of papers.

“You have a good night,” the policeman said to the driver, sending us off with a raised and blinking wand of light.

“ Kus okhtuk,”the driver mumbled, cursing his sister’s cunt. “Fucking Druze piece of shit.”

PRAYER FOR THE DEAD

“Oh,” Ruchaleh said, taking off her glasses, placing her book in her lap, and straightening up on the couch. “You’re home early.” Before setting off for Jaljulia I told her that I would be leaving right after my shift on Thursday and that I wouldn’t be back until Saturday night. She’d booked a different caretaker, the same one she used when we went out, usually on Thursday nights, for a movie and dinner.

“Yeah,” I mumbled. “Got back early.”

Recognizing that now was not the time for her usual cynicism, she sounded concerned when she asked, “What happened? You look wrecked.”

“How’s Yonatan?”

“Fine, fine. Sit down.”

I took a deep breath, put my bag on the floor, and sat on the couch, head down.

“What happened?” she asked again, and all I did was shake my head slowly and snort.

“You want a drink?” she asked, picking up a bottle of red wine. I nodded and she went to the kitchen for another glass.

“You don’t want to tell me what happened?”

“Um-Bassem died,” I said, and I filled my mouth with wine.

Um-Bassem died. I knew it as soon as I got out of the share-taxi. There was no doubt. There were men milling around the street, looking for a rock or something to perch on, men obviously called from work for a funeral. From a distance I could still recognize a few of them – the husbands of um-Bassem’s daughters who, despite having grown up, were still recognizable by the way they moved.

I walked toward them with my head down, pretending that I had come as they had, after receiving word.

“Allah have mercy on her,” I said, and shook the hands of a few men in the street. “ Ta’ish,”they said, as was customary. There were only a few dozen men present. The funerals of the elderly draw only kin.

The women’s voices could be heard from within the courtyard but I preferred to stay outside with the men. The separation is very clear in these kinds of affairs – men and women do not mix at all.

“Don’t be embarrassed,” the husband of um-Bassem’s oldest daughter said. “Go on in, put your bag down, wash your face. Don’t be embarrassed, there’s still no one but family in the house, there’s still time.”

“When did she pass?” I asked as I followed him to the house and, like him, I bowed my head and did not look at the women.

“Before dawn,” he said, looking at his watch. “But we waited for Bassem, may God help him. We’ve been telling him for a week to come immediately and say good-bye, but he hasn’t. What kind of job is it that keeps you from parting with your own mother? He just got here a second ago from the airport.”

“Amir,” I heard my mother’s voice behind me. She came out of um-Bassem’s courtyard toward me, her head covered with the colorful scarf she wore when visiting a mourner’s tent. Her eyes were puffy and red and she nearly hugged me but the look on my face and the way I shifted my gaze to the men in the road deterred her and she merely stroked my arm.

“Do you have laundry?” she asked, taking my little bag, probably hoping I did so that she could do something for me. “Are you hungry?”

“No,” I said, and I followed her into the house.

“How are you?” she asked, once the door closed and the two of us were alone.

“I’m fine.”

“Poor um-Bassem. But it’s better this way. More rest for her and for her daughters. She didn’t eat during these last months. Can I get you anything?”

“No, thank you, I had a falafel in Petach Tikva.”

“It’s good you came.”

“Yeah.”

“They’ve been waiting for Bassem all day. He just showed up now.”

“I heard.”

“So everything’s okay with you? Work?”

“Yeah, everything’s fine.”

“You have your own washing machine in the apartment?”

“Yes,” I said, and I knew she was looking at my shirt, which I hadn’t worn in over four years but had picked out of the closet that morning so that I could wear something that wouldn’t look strange to my mother and her neighbors.

“Don’t worry, Mom,” I said, walking toward the bathroom, trying to steady the tremble that had risen up from the balls of my feet to my knees and chest. “I have money.”

From the bathroom I could hear the teary voices of the women as they parted with um-Bassem. “Say hi to Daddy,” I heard the oldest daughter wail, and I assumed that the washing ceremony had been completed and that the coffin was being walked out of the house in the hands of the men.

“Amir,” my mother said, knocking on the bathroom door after a few minutes. “Amir, the funeral procession is leaving.”

Several dozen men trailed behind the coffin, which was carried to a nearby mosque on the shoulders of a few young men. The pace was brisk, as though everyone wanted to get this over with. Bassem looked a little tired but he smiled warmly whenever someone shook his hand and consoled him.

“Allah yirakhma,”I said, too, as I shook his hand.

“ Ta’ish,”he said, and I could tell from his face that he didn’t recognize me.

A young man near me answered his phone, which rang with the opening chords of Umm Kulthum’s “Enta Omri.” “I’m at a funeral right now,” he whispered into the phone, “I’ll call you later. Um-Bassem. Yes, Bassem. Died today. Ta’ish,’bye.”

A few dozen more men waited at the entrance to the mosque. The worshippers followed the body inside and began to say the prayer for the dead before burial. I stayed outside and tried to keep my eyes on the ground so that I wouldn’t see familiar faces.

“Hello, Amir,” said Nabil, a former classmate. “How are you?” he said, coming up to me and shaking my hand.

“Good, thanks.”

“Where’ve you been? We never see you around,” he said.

“In Jerusalem.”

“Oh, why? You still in school?”

“No. I graduated.”

“Wow, you were always one of the smart kids, weren’t you? So, do you make any money with this college job?”

“ Alhamdulillah.” Thank God.

“So why don’t you take your mother with you? Poor thing, I feel bad for her, all alone in the village, isn’t it a shame?” He smiled and looked around to see if anyone else had heard him, if anyone else was laughing along with him. “You know, as it says in the Koran, ‘show compassion for your parents.’”

“What about you?” I asked in a dry tone, signaling that I really didn’t want to hear anything more from him.

“ Walla,as our Jewish cousins say, blessed be God,” he said, kissing the back of his hand and thrusting it up toward the sky.

Nabil graduated elementary school without knowing how to read. Of the forty kids in our grade, there were ten or so who were completely illiterate. The majority just dropped out of school. Some went to trade school, with the best of the bunch learning car mechanics and the rest going into carpentry and metalwork. I couldn’t remember which route Nabil had taken, if any at all.

He leaned against the outside wall of the mosque and chatted quietly with his friends, occasionally stealing a glance in my direction. Nothing had changed. They were the same old kids, only larger. I could still see them at recess, sitting on the dilapidated benches and laughing at me.

“You got a hundred only ’cause your mother’s been going down on the principal,” they’d say. Or, “If your mother wasn’t a teacher in this school we would fuck you up bad.”

I’d often find notes with similar messages in my school bag, spelling mistakes and all. My mother was a teacher in the village’s only junior high. She never taught one of my classes, but that didn’t matter. My mother was different from the other teachers at the school. The kids cursed out all of the other teachers, ridiculed them behind their backs, but they would never dare tarnish their honor. My mother’s honor, all the kids knew, was free for the taking.

That’s how I learned that my mother used to show her tits to all the kids in the class; that my mother wore red bras and short skirts; that my mother was ousted from her village for whoring; that at night, after I went to sleep, my mother hosted all sorts of men in her bed; that she smoked cigarettes and drank alcohol; that she collaborated with the authorities; that she slept with policemen; that she slept with the principal; that they did it in the school library; that she’d been seen dancing at nightclubs in Petach Tikva; that she was sleeping with the math teacher, the history teacher, and the supervisor; that on the class trip she’d been seen peeing in the bushes and that she, for a fact, wore no underwear.

“Don’t believe a single word they say,” um-Bassem would tell me, even though I never told her what the other kids said. “Your mother is more honorable than all the rest of this trashy village. You must know that.”

Then, in junior high, I started to pray. I fasted during Ramadan and went to the religion lessons that our Koran teacher gave at the local mosque. During junior high I didn’t miss a single Friday prayer service. I became religious. My mother was a good mother. The proof: her son was a devout Muslim. I begged her to cover her hair, “For me,” for her to pray, at least on Friday, to stop smoking, to put in for a transfer to a different school, to transfer me to a different school in a different village. I didn’t mind taking the bus every morning or even walking to Kfar Kassem so long as it meant that I wouldn’t have to suffer kids like Nabil, leaning against the school walls and laughing at me.

I couldn’t figure out how it was that these overgrown kids could still intimidate me. You idiots, you assholes, if only you knew what I know. If only you knew what you look like to people who don’t live in these little hole-in-the-wall towns. If only you could see how lame your lives are. If you had even the slightest awareness of your social status, you’d lock yourself up in your house and never come out. The peak achievements of your lives are to be in charge of a construction site or to make your Jewish clients happy. Compassion is what you evoke in me, you and your big cars and your fancy houses. None of you will ever manage to escape from the trap in which you were born; none of you will ever venture beyond the boundaries of your village, boundaries that were drawn by another man’s hand. And especially you, the men, who think you’re so tough and manly, not scared of a thing, your voices so deep and strong they can stop a whole neighborhood in its tracks, you are the very essence of human trash. Keep on prancing around with your guns, keep on puffing up your chests while you do the Debka dance at weddings, keep on marrying virgins and let them preserve your honor and your male delusions. I know things you will never know; I’ve seen worlds you will never see. I’ve gone to places where you and your children will never be wanted. Yeah, me, the son of your whore, I will mock you to your face. I have nothing but disdain for you. Only I know what you’re worth.

“What are you smiling about?” I heard Nabil’s voice nearby. He stood before me, head cocked to the side.

“What? Oh, me, nothing,” I said, and um-Bassem came out of the mosque just in time to save me. “Allah Akbar, Allah Akbar,” I mumbled, following the coffin with my head bowed, and I knew then that as soon as the ceremony was over I’d grab my bag and leave.

GUEST ROOM

Over the past four years Yonatan’s condition had gotten worse. On the day that Ruchaleh paid my tuition for my freshman year at Bezalel, he was taken to the hospital.

“You’ll pay me back in installments,” she said when I refused to take the money, and she suggested subtracting five hundred shekels a month from my paycheck, even though we both knew that didn’t even cover half of the monthly tuition fees.