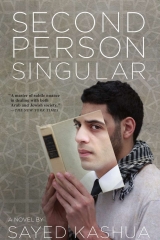

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

I stood before the lawyer, said nothing, and watched as he produced a pack of cigarettes and a lighter.

“You smoke?” he asked in Arabic.

I nodded and took a cigarette.

“ Tfadal,” be my guest, I said, and motioned him into the house, looking to see if anyone had witnessed our conversation. “You can smoke in here.”

He lit my cigarette and kept his unlit, clenched between his lips.

“Who are you?” I asked when he was seated on the couch. I had taken Ruchaleh’s usual spot and was feeling uncomfortable.

The lawyer’s gaze flitted around the room, taking in the books. “You know what,” he said, “I’ve always dreamed of having this kind of book collection. You want to sell it?”

“They’re not mine,” I said, trying to force him to get to the point, to stop gloating.

“And what about this one,” he said, knocking on the table where he’d set down The Kreutzer Sonata.“Is this one yours?”

“Please,” I said, “just tell me who you are and what you want.”

“Like I said, I’m a lawyer, but I’m here not as a lawyer but as Leila’s husband.” He stopped and looked me right in the face.

“Who’s Leila?” I asked, furrowing my brow, and I could tell immediately that he was relieved. His muscles seemed to slacken and he leaned back and lit his cigarette.

“You once worked at the outpatient clinic in east Jerusalem, right?”

“Yes.”

“Well then,” he said, flattening the note out on the table, “the whole thing started with this.”

I looked at the note, written in a very feminine and beautiful hand. “What is it? Where’s it from? That was in the book?”

“Yes,” the lawyer said. “That was in the book.”

“Okay,” I said, picking up the note, “what does that have to do with me?”

“She wrote it to you, did she not?”

“Who?”

“Leila, my wife.”

“Who’s Leila?” I said again, insisting that I did not remember.

“She worked with you at the outpatient clinic in Wadi Joz. You remember?”

“No, I don’t remember anyone by the name of Leila who worked there,” I said, traveling back to those days, to the clinic, to Wadi Joz, to the social worker I was supposed to be. “It was all boys there if I remember correctly, no?”

“There was a Leila there, too. She was an intern.”

“Ohhh,” I said, surprised, even though the lawyer did not seem convinced. “Yes, yes, I remember. You’re right. Wow, Leila. A student, right? We even once did a house call together in the Old City. How is she?”

“She’s well,” the lawyer said. “The question is how are you?”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“That means that I’m glad you were able to jump-start your memory and now I am going to need you to answer a few questions before I leave.”

“What kind of questions?” I asked.

“Questions like how did this note, written in my wife’s hand, which you claim not to remember, wind up between the pages of one of your books. And also, if you would, please enlighten me as to when all of this happened.” There was something firm and resolved in the lawyer’s look, something that showed me how distraught he was. He was sure I’d had a relationship with his wife and I knew I had to tell him the truth – otherwise everything I’d accomplished would go down the drain and I’d find myself answering the questions of real investigators, incriminating not only myself but those dear to me.

I took a deep breath and started to tell the story.

I don’t remember the note or how it made it into that book, but I do remember the book well. It’s one of the first books I read here, at Yonatan’s place.

“When did you leave the clinic?” the lawyer asked.

“Over seven years ago. And I didn’t leave, I fled.”

“Do you have an exact date?” the lawyer asked.

“No, not exact, but I’m pretty sure it was in January, seven years ago.” I could tell that the date I provided set him at ease, apparently because it added up with his own arithmetic.

“You have to believe me that I really don’t know a thing about your wife. At the time I was struggling with a few different things. I didn’t know if she was married and I didn’t care. I was in a very different place then, you see.”

“No, I don’t see,” the lawyer said, without even mentioning whether they were married at the time.

“I don’t know what this note is about. I don’t even remember it. I don’t even know if she wrote it to me or it just ended up in my book. Maybe she wanted to thank me for the house call. I really don’t know. All I remember is that one day I left them a resignation letter and I fled the office. I ran away from everything. Maybe this note was in the incoming-mail box, maybe it was on the table, maybe I just shoved it into my bag by accident.”

The lawyer began moving around in his seat, looking anxious. “What about the party? Or do you not remember that, either?”

“I’m not exactly sure what you want to know or why you want to know it. What party?”

“I want to know everything, Amir,” he growled. “And you want to know why? Because I found this note, which, as far as I’m concerned, is a love letter written by my wife, in a book that belonged to someone by the name of Yonatan. I want to know who this Yonatan is and how he’s connected to my wife and to you. Where is he, Amir?”

He was not going to leave without the whole story. He’d stay until he heard the whole thing. And the truth is I already started to feel myself wanting to tell. I wanted to tell someone everything that I had been through during these past years – the lies, the impersonations. To tell all, from the day I graduated and arrived at the house on Scout Street. All the things I couldn’t tell my mother or Noa or anyone else in the world. And maybe I also felt that he would understand.

I fought back the sob welling up inside me, took a deep breath, and started from the beginning.

“Yonatan’s dead,” I said. “I buried him a week ago.”

EPILOGUE

The lawyer looked at his watch and saw that it was already five thirty. He left the office and walked down the stairs and out to King George Street. Would he make it to the bookstore today? It had been several weeks since he’d last been. The lawyer wavered for a moment and then decided not to take any chances and headed back to the parking lot. He didn’t want to be late for the Thursday salon and dinner. This evening, he was pretty sure, they were going to meet at the accountant’s house, or was it the civil lawyer’s turn? He could not remember what they were to discuss, only that the gynecologist’s wife had festively announced the topic at their last meeting. No harm done; his wife probably knew. Of course she knew. Soon she would call to remind him to get a good bottle of red wine and some fine chocolate for the hosts’ kids.

Not that the lawyer lacked reading material. He still hadn’t even had the chance to read through all of Yonatan’s books. Truth be told, he hadn’t read any of them aside from The Kreutzer Sonata.He praised the novella, told Tarik, Samah, and the rest of his Arab friends that it was “an amazing work of art,” knowing full well that there was no chance in hell that they’d read it. His next book was Life: A User’s Manual—a thick and impressive tome by some French author whose name the lawyer had forgotten, and even though he was never really able to focus or follow the plot, he forced himself to read a few lines before sleep, mostly because, from what he’d learned on the back cover, the Frenchman who’d written the book was so important that he’d had a planet named in his honor.

The lawyer, promising himself a new book the following Thursday, hurried off to his car. He had to buy wine and chocolate and shower and get dressed for dinner, but before all that he had to make it to Bezalel. He wanted to see Yonatan’s show.

Why was he going? the lawyer wondered as he lurched down the steep and narrow Hillel Street. He had not been invited to the graduating class’s year-end exhibition but Yonatan had mentioned it once or twice during their subsequent conversations and it seemed to the lawyer that he wanted him to come. But why did he want to go? In the morning, at Oved’s Café, he’d heard the art history professor telling a friend that he’d seen some “extremely compelling” works at Bezalel’s year-end exhibition, including one outstanding project by a graduating photography major. The lawyer, sure the professor was referring to Yonatan, felt the jealousy begin to bubble.

Why was he so jealous? After all, the lawyer believed Yonatan’s story. He believed him even when he said that he didn’t remember Leila’s note and that he could hardly recall her name. But the fact that she might have had a relationship with a talented, perhaps successful artist rattled him nonetheless.

All things considered, the lawyer thought as he lit a cigarette with the electric lighter in the car, Yonatan’s revelations had only improved his relationship with his wife. After their initial meeting on Scout Street, the lawyer had come home full of love and lust for his wife, so much so that he decided to alter his sleeping habits and return to her bed.

“We have to force the kids to sleep in their rooms,” he had told his wife as he took his daughter down to the ground floor and moved his son’s crib into his room. The feeling was wonderful: he desired his wife, fell back in love with her, and, despite the discomfort, even insisted on spooning before sleep. When their daughter came upstairs crying in the middle of the night, the lawyer insisted that she return to her room. His vigilance lasted for several nights. After that he gave up and let his daughter back into the bed and resumed sleeping in her room downstairs. What can you do? he thought. With all due respect to love, I sleep much better alone.

What would he say if he met Yonatan at the exhibition? Walking toward the art academy, the lawyer tried to formulate the sentences that would explain his presence. But why did he even need to offer an explanation? The show was open to the public. They would surely speak in Hebrew, only in Hebrew. He could say to Yonatan, I remember you mentioning the opening and art has always interested me so I decided I’d swing by,or he could mention that he had heard about the exhibition from a friend, a professor of art history, and had decided that he couldn’t afford to miss it. After all, he also liked art, especially the work of a certain Egon Schiele. The lawyer’s apprehension quickly changed shades, turning into a desire to know what “Yonatan” was like in public, among his friends, among the artsy crowd in attendance, and to see his reaction when he saw the lawyer – whether he blushed when he lied, whether his lies were transparent, and whether this charade was something he could really pull off.

The lawyer walked through the gates and onto the campus and stood before a sign that pointed the way to the different exhibits – plastic art, visual media, ceramic design, architecture, and other shows that did not interest him in the least. He looked for the arrow that pointed the way to the photography exhibit.

There was very little foot traffic in the photography wing when he got there. Each time he heard steps along the hard floor, the lawyer spun around to look for Yonatan. There were different-sized photos hung on the walls of the open classrooms and along the halls. The lawyer tried to walk slowly and lend himself the air of someone just taking in the arts even though what really interested him was the little white rectangle next to each photo, where the student’s name was presented.

The lawyer, looking for Yonatan’s work, toured the halls and the classrooms, gazing at landscapes and rotted-out buildings and portraits of people who glared at him, generally in the nude. There were also plenty of unclear photos, cut in the middle or blurred or splotched with color. He walked into the classrooms and, if they were empty, he made do with a glance at the name of the student presenting. If there were others milling around that particular exhibit, then he forced himself to make a round, eyeing the pictures at a hurried stroll.

The third room he entered was Yonatan’s. All it took was one glance and he was set at ease: these were not the photos that the art history professor had referred to earlier in the day. There was no way that these old photos, in black and white, were outstanding or compelling. He himself had already seen more interesting photos in that day’s paper.

“To my mind,” the lawyer heard an older woman whisper to her partner, “this young man’s work is the most interesting of all.”

“Yes, he’s a real talent,” her authoritative partner said. “What’s his name?”

Please, no, no, the lawyer prayed before hearing the woman say, “Forschmidt, Yonatan Forschmidt.”

The lawyer looked very carefully at Yonatan’s prints, the faces along the wall. He felt he had to understand what had so impressed the elderly couple, for whom art exhibitions were surely a way of life. He breathed in deeply and started to examine the expressions on the people’s faces, the wrinkles, the pupils, the sad smiles, every last one of the details that Yonatan, that bastard, knew how to zero in on. They really are impressive, the lawyer thought, looking at the close-ups of the children, teens, women, and men. The lawyer, who was always proud of his ability to discern between Arab and Jew at a glance, had a hard time determining the ethnicity of these people.

He looked at his watch. He still had some time and he lingered in front of the prints and thought of the best way to express his enthusiasm to Yonatan, if he should bump into him. All told, there were twelve prints on display, eleven of which were portraits. Suddenly the lawyer was drawn to the twelfth one, which was positioned apart from the rest, in the corner, as though someone were hiding it from him.

The photograph was of a naked back, the arched back of a woman on the edge of a child’s bed. He approached the picture slowly and felt his heart rate rise as he drew nearer to the woman’s bared back. Ashamed of what he was doing, he looked over his shoulder to make sure no one was coming. This picture, also in black and white, had been taken in a rather dark room, and he imagined that Yonatan had trained a soft yellow night-light at the woman’s back. The complexion of her skin, her hair – trailing down the nape of her neck in a few scant ringlets – were of an indiscernible shade.

Again he made sure that he was alone in the room and then took one more step forward, so that his nose almost brushed against the print. He stared hard at the spot where the woman’s behind touched the bed, at her scapula, her spine, her neck. Suddenly he put a hand out to caress the naked woman’s hips. He could have sworn they were Leila’s.