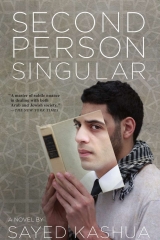

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Sometimes I’d fall asleep on the bus and the drivers would wake me up at the last stop. I always apologized, got off the bus, and waited for another one. Most mornings I was in the Old City, where I’d eat a late breakfast of hummus and fava beans. After that I’d take a bus to Sacher Park and sit down with my book under a tree, passing the hot hours of the day in the shade. Sometimes I’d fall asleep, but not usually. Then I’d walk up to the nearby Nachlaot neighborhood, take a walk through the marketplace, go up King George, down Ben Yehuda, and around to Nahalat Shiv’a. About an hour before my shift started, I’d get a falafel sandwich or two. Half an hour later, I’d take a bus from downtown to Beit Hakerem.

A week of endless wandering was enough. I realized there was no way I could go on like that. This was in early September and I knew that soon Jerusalem would start to get cold. What would I do then? What would I do when it rained? At first I thought I’d just go to the university and spend my time in the library, but I didn’t want to run into old acquaintances from school or the guys from the office or, least of all, Leila. At some point during the day I always thought about going back to my mother’s house, but that notion retreated under inspection.

It didn’t take me long to get back in the habit of sleeping at night. At first for just an hour or two, but within a week I was up to four hours a night. The rest of the time I soothed myself with music, books, and, especially, the camera. I wished I hadn’t burned through all the film on the first night and that I could see the pictures I had taken. I played with the camera every night, putting pictures into focus and pushing the button even though I knew nothing would happen. I wasn’t sure what you did with the film that was already spent, how you took it out and got it developed. One morning, though, feeling audacious, I snuck the camera into my bag and took it out of the apartment for the first time.

“Wow,” said the shopkeeper in the Armenian Quarter as he sipped his coffee, “this is an excellent camera. Russian. They don’t make them like this anymore.” He gripped the camera, looked through the viewfinder, and started to mess with the lens and a few other dials. “There’s nothing like a 50mm lens,” he said, “it’s the best. No zoom, no nonsense, just like in real life.” I told him I had bought the camera from some Jewish guy and that I was still trying to figure it all out. “Does it still have film in it?” he asked, looking at the knob and the numbers.

“Yes,” I said, nodding.

“Do you know how to take it out?”

“No,” I said, trying to smile. “I mean, I didn’t want to ruin it.”

“Here, look,” the Armenian said, pushing a button on the left side of the the camera and swiveling a little handle. “You have to keep this pressed the whole time,” he said, showing me the button, “and you swivel this all the way till the end. Here, listen.” We both stayed quiet and waited to hear the sound of the film safely back in its roll. Then he pulled a little lever and the back of the camera popped open, the roll of film visible. “That’s it. You take it out like this. This roll’s black and white. You want it developed?”

“Yes,” I said, and the Armenian popped the roll into an envelope and wrote my name on it.

“It’ll be ready tomorrow,” he said, to my great disappointment. I had thought it would be just a matter of minutes.

“You want a new roll?” the Armenian asked.

“What? Oh, yes, yes, thank you,” I said, consoled by the prospect of taking more pictures.

“Black and white?”

“Yes,” I said, “black and white.”

“What ISO speed?”

“Excuse me?”

“The ISO speed relates to the film’s sensitivity to light. The higher the number the faster it responds. There’s one hundred, four hundred, and more. Do you shoot at night, too?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Take the four hundred then,” he said, grabbing a roll off one of the shelves. “Do you know how to load it?” he asked, and without waiting for an answer he popped open the back again, made sure I was paying attention to what his hands were doing, and put the film in the chamber. He fed the front end into a spool and hit the shutter-release button.

“The first two or three frames are goners as soon as the film is exposed to the light so just advance right on through them.”

The film cost fifteen shekels and the Armenian, who saw the surprise on my face, said, “I gave you the highest quality stuff.” I put the camera around my neck and headed out to the Old City.

EIGHTEEN SHEKELS

“Each picture’s a shekel,” the Armenian told me with a smile the next morning, and I cursed my new hobby under my breath. “All told, it’s eighteen shekels,” he said, handing me a bright yellow envelope. It took a moment until I understood.

“Eighteen? Why eighteen?

“Because all the other ones were overexposed,” he said. I knew right away that the eighteen that survived were the ones someone else had taken before me. The little wheel had been on the number 21 and I already knew that the first three shots couldn’t be counted. I was crestfallen and the Armenian made a gesture with his hand for the camera.

“Do you know what an aperture ring is?” he asked and all I did was shake my head. “You took a picture in the dark and didn’t compensate by slowing your shutter speed,” he said, watching to see by my response if I had any idea what he was talking about.

“Look through the viewfinder,” he instructed me, putting the camera near my face. “You see that little needle moving left and right?”

“Yes.”

“That’s the aperture. When it’s in the middle it means you won’t over– or underexpose a picture. Where is it now? Closer to the minus or the plus side?”

“The minus,” I said, and I wondered how I hadn’t noticed those signs staring at me from deep within the viewfinder.

“That means there isn’t enough light. You either didn’t open the aperture wide enough or you put the shutter speed on too fast a setting. You have to learn how to play with these things. Here, let me show you.”

The Armenian took the camera and started tinkering with a button I hadn’t seen before.

“This is the aperture,” he said. “You can open or close it depending on how much light you want to let in.”

He toyed with the ring of the lens, with something that said f-stop on it, and showed me how the small numbers let in a lot of light and the big ones blocked it out almost entirely. Then he put his finger on a button, the one that determines the shutter speed, and went on and on about how you have to balance the two of them, walking me in and out of the store to see the difference between natural light, electric light, and darkness. In the end I paid him eighteen shekels for pictures I didn’t really want and left the store. I was pretty sure that the day before I had already managed to overexpose five shots.

Not hungry, I walked east, out of the Armenian Quarter and toward the square outside the al-Aqsa Mosque. The Armenian had said that the wide open square caught the early morning light and was an ideal spot to learn how to play with the aperture and the shutter speed. “I guarantee you,” the Armenian said with a smile as I left his store, “that you won’t overexpose more than two more rolls of film.”

On the way to the mosque I did the calculations: I could afford five rolls of film a month, no more. The film would cost

75 shekels a month; the development of 33 photos per roll would add another 165 on to the bill. Back then 240 shekels a month was a fortune. My salary was only 2,500 shekels a month, but at that time my attraction to the camera was stronger than anything else. At first I thought it was just some unemployed man’s hobby, the kind of thing that would pass with one more roll of overexposed film. But I had this real desire to take pictures and, especially, to see the pictures I’d taken once they were developed. Nights, I went through Yonatan’s boxes of photos and noticed things I’d never seen before. Yonatan mostly took pictures of people. Before I’d found the camera, I would just flip through the pictures and try to guess if they were taken at a family event or on a class trip. But what had been rather dull was now fascinating. Yonatan did not take pictures at events or weddings or birthday parties. He photographed people and their expressions, freezing and preserving moments of sadness, fear, contemplation, happiness, and worry.

I arrived at the square outside the mosque and knew that I had no intention of photographing old domes and other tourist attractions. People, that’s what I wanted to capture on film. I wanted to see if I could be as precise and knowing as Yonatan, if I could also take the kind of sharp, detailed pictures that revealed the entire world of the stranger on the other end of the lens.

The guards at the entrance to the square asked to see identification and let me in only once they’d verified that I was a Muslim. It was early, and between prayer times, so the square, which was usually full of careening kids who had nowhere else to play, was nearly empty.

A few beggars asked for spare change and I ignored them, knowing that if I coughed up a single cent I’d be hounded all the way out of the Old City, followed by their outstretched hands and sorry eyes.

“Excuse me,” a bearded man said, striding toward me with a walkie-talkie. “Wait,” he commanded and I stopped. “Are you a Muslim?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“Muslim,” he said, raising his radio to his mouth. “I’m sorry, your appearance was misleading. The camera made me think that maybe. . where are you from?”

“Jaljulia.”

“Welcome,” he said, bringing his palm to his chest.

I sat down on the stairs that led from the al-Aqsa square to the Mosque of Omar. I looked around and saw there was nothing that I really wanted to photograph. I opened the yellow envelope the Armenian had given me and took out the eighteen pictures from the previous roll of film.

I saw Yonatan, an eighteen-year-old Yonatan, standing on his own two feet. In the first photo, he held the camera that I now had around my neck. He had held it down around his waist and taken a picture of himself in the mirror in the attic bathroom, a sealed, sharp expression on his face. I flipped to the next picture: Yonatan, standing by the side of the bed. He held a release cable in his hand, the kind that lets you operate the camera from afar. The cable, I thought, wasn’t in the photo by chance. He knew what he wanted in his frames. In the third photo, he was standing on a chair in the middle of the room. In the next one, he threaded a rope through an anchor for the light fixture in the ceiling. I started breathing quickly, racing through the photos. He was in all of them. He tied the noose. He took a shot of himself from below. He moved the camera away and took a picture of himself testing the rope. And always the same expression, cold, emotionless, remote. He had taken a few different shots of himself, from various angles, with his neck in the noose. I felt starved for air. I stood up and tried to inhale properly, but still I could feel myself shaking. Yonatan stood on the back of the chair and in the last photo, number 18, I saw him push the chair away with his feet. Behind him, very vividly, I could see the bed and the pictures on the wall, but the center of the frame, where the body hung, was blurry, the neck, stomach, hands, and feet were all elongated, and I knew that he had used a slow shutter speed and a long exposure.

THE CARDBOARD BOX

I showed up half an hour early. There were two girls in the waiting room. Each had a big square art bag and they were chatting. They stopped their conversation for a second when I showed up, looked me over, and nodded in my direction. I nodded back, then lowered my eyes and went to check out the list of names on the door. I was number five.

“What time did they call you for?” one of the girls asked. She was skinny, with blonde hair that had been dyed purple.

“Eleven thirty,” I said.

“They’re running ridiculously late. The ten o’clock just went in now. How far down the list are you?”

“I’m fifth.”

“Cool, I’m fourth.”

“I’m sixth,” the other girl said softly. “After you.” She was more filled out than her friend and she wore a Ministry T-shirt. She noticed that I was staring at her shirt and lowered her eyes, and I, fearing she would think I was looking at her chest, said, “I have the same shirt.” She nodded and smiled. Her breasts were round and full and I could see the shape of her nipples through the fabric.

Each applicant had a half hour slot, and if the skinny one was right and the third on the list had only gone in now, then I had at least an hour until it was my turn. My first thought was to flee, to give up; what were the chances of me being accepted to the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design? Knowing I didn’t belong, I sat down on the floor and leaned my back against the wall, opposite the girls.

“If the whole point of photography is to capture a single moment in time, I figured why not go for it, you know?” the skinny girl said. “I figured I’ll just go for it. I’ll photograph time. Or what time means to me.”

She picked up her portfolio, laid it on her knees, and started taking out photographs in black matte frames. I couldn’t see the photos she passed along to the other girl, one after another, carefully, as though handling the pages of a holy book. Every once in a while she blew dust off the surface of a photo and carried on with her presentation.

“To me this represents the passing of time, and here I tried to understand and conceptualize the meaning of the present, and here at the end I tried to capture the future as I see it, in other words, within the infinite space of time.”

The girl with the Ministry T-shirt seemed to find the skinny girl’s presentation interesting, and I knew there was no way I could carry on like that about time, and what’s more I realized that I had not framed any of my photographs. It was a mistake to come. I had no idea how I had ever made it through the first stage of the application process, but I knew for sure that I was not an artist. The Ministry girl glanced up for a moment and caught me looking at her. She smiled at me and I smiled back.

“And this is my self-portrait,” the skinny one said. “A woman with no head and no limbs.”

I made a face and just at that moment the Ministry girl looked up at me and burst out laughing.

“I’m sorry,” she said, trying to keep her poise. “I’m really sorry. He’s just making me laugh,” she said, pointing at me.

Several long minutes later the door opened and a young dark-skinned guy with long curly hair emerged. He was well-dressed, clothed from head to toe in designer apparel. He inhaled deeply and shut the door. The skinny girl hopped up.

“Well, what did they ask?” she clamored.

“You know, just questions about my work, where I’m from, why I want to study here, that kind of thing,” he said in Nazareth-accented Hebrew. The door opened again and a woman with a file in her hand summoned the skinny girl.

“Good luck,” the cute one said, and I mumbled after her, “Good luck.”

Just before the woman shut the door, the guy from Nazareth asked when he could expect results and she said within a month and then closed the door.

He was bursting with confidence. He said he had also applied to the department of architecture and that if he got in there he would definitely go, but that if he didn’t, he’d do a year of photography and then reapply to architecture at the end of the year.

“He definitely got in,” the Ministry girl said when we were left alone in the waiting room. “To photography andto architecture. They’ll probably fight over who gets him.”

“You know him?” I asked.

“No,” she said, shrugging, “but this is Bezalel. They’d kill to have an Arab in the program.”

“Maybe he has competition in the department of architecture,” I said, smiling.

“You’re right,” she said. “I hadn’t thought of that. Two Arabs is already too much.”

The skinny one walked out with a big smile on her face.

“How’d it go?” number six asked her halfheartedly.

“Hard, stressful, but I think it went well.”

“Yonatan, Yonatan Forschmidt,” the woman with the file said and I jumped up from the floor and straightened out. “That’s me,” I said.

“Good luck, Yonatan,” number six said.

Yonatan Forschmidt. That’s the name I’d put down on the application, the name I’d used for the psychometric exam, the name that had appeared on the sheet in the waiting room. For the previous six months I had been walking around with Yonatan’s ID in my pocket, or rather, to be exact, with two IDs – his, which I’d found in the attic, and mine.

I remember how scared I was the first time I’d identified myself as a Jew. It was in a café on Ben Yehuda Street, the fifth one I’d gone to in search of a job. The boss looked at Yonatan’s ID, eyed his old picture, and then filled in his personal details on the application without any hint of suspicion. In all of the other cafés, where I’d identified myself as an Arab, the bosses suddenly didn’t have waitering positions available, despite the waitstaff wanted sign on the door. Either that or they offered me a job as a dishwasher. I agreed to that once. It was called chef’s assistant, but all I was asked to do was wash dishes, clean the bathrooms, bring in the supplies, and take out the garbage. I had to come in at seven thirty in the morning and stay until six in the evening and my pay was minimum wage. I knew that the waiters worked less and made more. All of the waitstaff were Jewish and all of the kitchen workers were Arabs: the ones the customers didn’t see were always Arabs.

Once I’d gotten the job by posing as a Jew, I felt embarrassed by what I’d done and decided I wouldn’t show up for my first shift. But I needed the money and I convinced myself that I had not done anything wrong. Just a little hoax so I could get a reasonable job. The first week was training and throughout that period I focused on not answering the kitchen staff in my native tongue when they said good morning in Arabic or asked if I’d like something to eat. The training went well and the owner saw that I could be trusted. I always showed up on time, didn’t ask for days off, didn’t come in tired, and was generous with the customers, even the most difficult ones.

The kitchen staff consisted of Muhammad, whom everyone called Mukhi; Rafik, whom everyone called Rafi; and Suleiman, who preferred to be called Soli. All three of them were from east Jerusalem, and all three of them smoked, prayed, and talked about girls all the time.

As opposed to the waitstaff, who were given their shifts in advance, Mukhi, Rafi, and Soli worked all day every day, from seven in the morning until midnight, except for Fridays, which were short days, and Saturdays, when the café was closed.

My relationship with the owner, the kitchen workers, and the other waiters was polite, nothing more. I didn’t let anyone get too close to me, especially not Dana, a young waitress who, like me, preferred the morning shift – she had Bagrut matriculation courses in the afternoon. She was a pretty, smart girl who had dropped out of high school because she couldn’t stand the teachers, the other kids, and the material that was being taught. Nor could she stand the sleazeballs and bimbos who went to the Bagrut courses in the afternoon instead of high school, but she had no choice. She wanted to go to college, probably to study psychology or art history; she wasn’t sure. She invited me over to her place in the Nachlaot neighborhood for Saturday brunch but I had to restrain myself and say no. Back then, I couldn’t imagine lying to other people about my identity, although, after spending a night practicing the signature he’d left in his books, I had opened a bank account in Yonatan’s name. I told myself that my lie was solely for the purposes of work, and it could not be allowed to spread to my personal life, even though I wasn’t sure I had one of those.

“Your portfolio, please,” the woman with the file said, and I already regretted coming. I opened my bag and took out a cardboard box, my portfolio. The three members of the admissions committee sat around a round table: the chair of the department, an instructor, and a fourth-year student. They looked over the paperwork in front of them and waited for me to take out my work.

The applicants who had made it through the first two stages of the application process were asked, for the final stage, to do three things: a story in ten pictures, a self-portrait, and three pictures of your choosing. I gave the secretary my box.

“What’s this,” asked the instructor. “Store-developed photos?”

“Yes,” I said. He started looking through the first photos, my story in ten pictures. In contrast to those of the skinny girl from the waiting room, my pictures were all standard size. The Armenian had developed them for me and I had not even thought of blowing them up or framing them.

“When did you start taking photographs?” he asked.

“A year ago, about a year ago.”

“Did you study anywhere?” he asked, without taking his eyes off the photos.

“No, I studied alone. I mean, someone showed me the basics and I read some books,” I said, and the instructor passed the ten photos to the head of the department.

“So you didn’t study photography in high school or anywhere else?” the instructor continued.

“No,” I said, and I felt myself blush. I hated myself for having the gall to come to this place, for listening to Osnat and Dana, who said I would get into Bezalel with my eyes closed.

“Do you have your camera with you now?” the head of the department asked, spreading the photos out on the table so the student could see, too.

“Yes,” I said. “I have it here.”

“Let me see it, please,” the department head said, and I opened the camera bag, which had almost always been on my shoulder during the past year and a half.

“Wow, a Pentax,” he said, when I handed it to him. “Do they still make these?” The department head held the camera in both hands and passed the rest of the pictures over to the instructor.

My portfolio consisted of portraits. I asked permission and I photographed people. Yonatan had focused on portraits and I studied his work at night, tried to understand what it was about his photos that drew me in. I also studied his books, which dealt only with the art of portraiture, and I looked over each and every photograph under the lamp in the attic for hours. Since I’d learned how to use the camera, I’d been taking pictures of people, especially in the Old City.

Ruchaleh had split the caretaking work into three shifts and I took the afternoon and night, back to back, and that, along with the waitering, left me a lot more money for photography. After a few weeks at the café I worked up to asking the owner if I could take pictures, and I started shooting on the premises, taking pictures of the employees once they’d given me their permission. I used those for my story in ten pictures. They were portraits of the kitchen workers, from the moment they were given an order until they slid the dish out from under the window in the wall that divided the café and the kitchen and hit the bell. I had also been taking pictures of the café regulars, the ones who came each morning, and for the category of three pictures of my choosing, I picked Sara, who, so long as she wasn’t in the hospital, came to the café each morning along with her Filipina caretaker. In the picture I submitted, she was holding a cup of tea in both hands and smiling with her eyes. The other two shots were from the Old City: one of the Armenian laughing, a gold tooth glinting in his open mouth, and the other of a border policeman smiling as he checked my ID, which is to say Yonatan’s.

“Hold on,” the department head said, sifting through the pictures on the table, “I’m missing the self-portrait.”

P.O. BOX

I hurried out to check the mail the next day to see whether I’d gotten an answer. After applying as Yonatan I’d also gotten myself a post office box with his name. You had to have a mailing address to put on the application form and I remembered from back when I was a student that some of those who didn’t have a permanent address rented a post office box. Before mailing the application off to Bezalel, I rented a box for a few dozen shekels at the King George Street post office, near the café where I worked. Each morning, on the way from Beit Hakerem to the café, I stopped in at the post office and checked my box. Sometimes I found advertisements or mail with someone else’s name, but now an entire month had passed since the interview and I had not heard a word from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design.

Before the interview I had not been sure I even wanted to go there and I was pretty sure that even if I did want to there was no way I’d dare embark on a four-year degree with a stolen identity. But once I’d gone to the interview there was nothing I wanted more than the piece of paper that said I had been accepted. I wanted to know that I had convinced the panel that my photographs were good enough to continue on in the field. I just wanted to be told that I was good. I constantly imagined myself reading from a piece of paper embossed with the Bezalel seal, “We are pleased to inform you. .” During those days of waiting I was estremely sorry I had not completed the third assignment, the self-portrait, even though the head of the department had smiled forgivingly when I offered my explanation for its absence: “It hasn’t come into focus yet.”

By the fourth week of waiting, I had convinced myself that applying to Bezalel’s school of photography had been a terrible mistake. Sure I loved photography more than anything else, but I was a naive idiot, believing that a few months of tinkering would get me into the most prestigious art school in the country, one that only took a handful of students each year, all of whom had studied art in school, not learned it on their own in an attic that reeked of medicine and having their pictures developed in an old machine in a crummy store in the middle of the Armenian Quarter.

School was set to start in a couple of months and I knew that the acceptance letters must have been sent long ago. Clearly I had not gotten in. Two months was too little time, especially for out-of-town students who had to find a place to live and get settled in Jerusalem before the school year started. Nonetheless I continued to check the post office box every morning and afternoon. In the middle of the week, when the café was relatively empty, I’d head out and check the box compulsively – sometimes five times in a single shift. During those days I started to get the feeling that someone was onto me, that they’d discovered my true identity, because even if I’d been rejected I should still have been given notice of some kind. Maybe someone who’d known Yonatan in school or someone who knew the Forschmidt family, or someone who knew me, who picked up the foreign intonation and had his suspicions had turned me in. The criminal implications of what I’d done, the theft of Yonatan’s identity, suddenly became clear and in my mind I no longer saw myself reading an acceptance letter but began to envision police officers arriving at the house in Beit Hakerem or at the café, or, worse, at my mother’s place, looking for the imposter. All I wanted was some word from Bezalel, preferably a rejection letter, so I could put the whole affair behind me and get rid of all the stress.

I tried convincing myself that I’d get a pretty lenient sentence. I’d be arrested, no doubt about that, and I’d have a criminal record, but since the identity theft had not been for the purpose of fraud – the pictures were truly mine – I probably wouldn’t have to do time, at least not a lot of time. I had been asked to provide a Bagrut certificate and I had given them Yonatan’s, but I had one of my own and mine was just as good as his. My assumed identity for the purpose of work at the café didn’t seem like the kind of crime you did time for, either.

“Your Honor,” I imagined myself saying from the stand, “all I did was provide a different name than my own. Ask the owner, though, I was his best worker. Ask the clients. My sole intent was to get a job as a waiter and not a kitchen worker.”

The prosecution’s attempts to attribute a nationalistic element to the crime, to say that my goal had been to harm Israelis, would surely be discredited by the brilliant young lawyer, Majdi, whom I would have to contact even though I had no idea how I would explain my actions to him. It would be easy to show that I was not politically active. I’d never been in a rally, never voted for the Knesset, never voted in the local council elections, never even voted in the elections for Arab student council or in the general elections on campus.

“A waiter, Your Honor,” I imagined myself concluding my argument. “All I wanted to be was a waiter.”

I used to spend the afternoons, on my way from the café to the house, thinking about an immediate escape. I practiced the lines I would use on Osnat. “Please tell Ruchaleh that there’s been a family emergency.” Or, “I have to go home and be with my mother.” Or, “There’s a bit of trouble in the village.” All lines that were tailor-made for Osnat and Ruchaleh, spiced with a dash of mysterious Oriental drama so they wouldn’t ask too many questions, merely accept that a situation had arisen that required my immediate attention. I had to be with my mother, and they would understand that I had no choice but to leave and they would find someone else on very short notice to pick up the shifts. But what if they didn’t forgive me for leaving like that? What if they were offended? Well, screw them, I thought to myself. True, they didn’t ridicule me or underestimate me, but the salary they had been paying me was a joke. The monthly salary did not correlate at all to the sixteen hours a day that I worked, and the only reason I was able to get by was because I had no rent to pay and I made do with a fold-out couch for a bed.