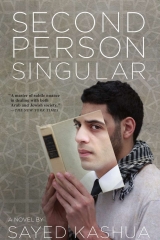

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

OXIMETER

Late that same Thursday night I called Noa.

“If you’re not working,” she said, “then I’m free. It’ll be the first time I get to see you after nightfall. I was starting to think you turned into a pumpkin at midnight.”

I hailed a cab on Herzl Boulervard and took it to her house on the corner of Agrippas and Nissim Behar in Nachlaot. I went up three flights of stairs to the apartment Noa liked calling “the studio.” She’d moved in during the summer between junior and senior year. Before that she’d lived with two roommates in a bigger apartment in the area, but that came to an end when one of the roommates began inviting over a rabbi with a white kippahand a pervert’s grin. Noa said she hated all the Rainbow and Shantipi crap.

She did not hit the India travel circuit after the army. “Even if I had gone to the army, I wouldn’t have gone to India,” she said. She had a hard time understanding how it was possible to beat the shit out of Arabs all through army service and then run straight into an ashram and feel all pure. Nor had she gone to South America. After high school she went to Europe, then she spent a month in New York City, and then she started school in Jerusalem.

She hated her hometown, Hod HaSharon. The place is disgusting, she said. Afterward she lived in Ra’anana and she detested it, too, said it was even more disgusting. Her father was a doctor but he didn’t work in medicine. He started his own company, importing medical supplies. Her younger brother, the “king of the nerds,” as she called him, seemed poised to follow their older sister, who was also a doctor and worked with her father.

“My mother is actually an amazing person,” she said, an artist at heart who had worked as a nurse for many years and now also worked in the family business. “What about you?” she would ask now and again. “I don’t know a thing about your family.”

“I don’t have one,” I’d say with a smile. “Somewhere out there I’ve got a mother.”

Noa was my girlfriend. At least that’s how I used to refer to her in front of Ruchaleh, who used to say, “Come on already, when are you going to bring her over?”

But what exactly was I supposed to say to her? Noa, this is my boss, we just happen to have the same last name.And what exactly was I supposed to say about the man in the attic– Meet my brother, we’re twins. Fraternal not identical, and, yes, he was in a terrible accident?

We’d meet up during the day, usually on Saturday mornings if she hadn’t gone back to her parents’ house for the weekend. She didn’t go there often and she would get angry with her mother whenever she forced her to visit, once every few months. The two of us would go on trips together, take photographs, drink coffee, hug when times were tough, hold hands, exchange CDs, download music, and on Thursdays, half days at Bezalel, we’d shop for records and check out photography exhibits. I liked hanging out at her place and she liked having me there. Sometimes she’d get all worked up, visibly furious, and she’d throw me out of the house.

“I need to be alone for a little while,” she’d say, starting to cry, but then she’d calm down, invite me back in, suggest we do something together, maybe a walk around the neighborhood or a stroll through the Old City.

“You look different,” I blurted out when she opened the door that evening. I’d never seen her dressed up before. In school and when I came by on Saturday mornings she always wore jeans or cords and a T-shirt. Now she stood in the doorway in a gray skirt, the kind that the lawyers wear on American TV shows. Instead of a funky T-shirt she wore a red sleeveless blouse that buttoned up the front. There was lipstick on her lips and black mascara on her eyelashes. I’d never seen her made up before.

“What do you think?” she asked, her hands trembling. “Kind of like a babushka doll?”

“Kind of,” I said, laughing. “I feel bad, I’m in my work clothes.”

“Do you want me to change?”

“No, no, not at all. . it’s just. .” I wasn’t sure how to finish the sentence.

“Just what?”

“Nothing.”

“Come on, say it, you bastard.”

“Say what?”

“That I look beautiful.”

“You look beautiful.”

“Yeah, thanks a lot.”

“No problem.”

“Hold on, let me grab a shawl or something,” she said and turned back into the house.

“Are we going out?” I asked, and I checked to see how much cash Ruchaleh had stuffed into my wallet.

“Yeah,” she said, smiling. “You want me to sit around the house like Little Red Riding Hood in this thing? Of course we’re going out. Don’t you want to?”

“Yeah, of course. I’d love to.”

“Good,” she said, and she shut the door behind her.

“Where do you want to go?” I asked as we walked down Nissim Behar.

“Your call.”

“Ahhhh,” I asked, unprepared. “You hungry?”

“A little bit, not really, maybe a little something.”

“Okay,” I said and I took her hand and then turned it over and looked at her watch. She smiled and I felt a surge of desire.

“I think Cavalier is still open.”

“Cavalier?” she asked.

“It’s a great restaurant.” It was one of Ruchaleh’s favorites.

“What are you talking about?” she asked. “How the hell did you get Cavalier into your head?”

“I don’t know, it’s in walking distance. If you want to take a cab we could also go to the American Colony. The food there is pretty good, too.” I knew that those were two of the most expensive restaurants in the city, the kind students walked into only through the staff entrance. One time, when we went to Arkadia, our waiter was a guy in my class. Ruchaleh didn’t hesitate. She shook the guy’s hand and said, “Nice to meet you; I’m Yonatan’s mother.”

I didn’t know much about Jerusalem’s night life but I wanted to impress Noa. I wanted her to know that I was hiding something, that I wasn’t just some loser student, working nights and forgoing any semblance of a social life in order to pay tuition.

“Those are the options you’re giving me?” she asked, laughing. “When I said I was a little hungry, I was thinking that, like, maybe we’d order some fries with our beer, not Cavalier.”

“You know, I have a feeling you know the city a lot better than I do at this point. You decide.”

“Okay,” she said. “Follow me.” And she took my hand in hers, looked for my response, and when I smiled, she tightened her grip and tugged me down the road, saying again, “Where the hell do you have the cash for Cavalier from?”

I had the cash. Ruchaleh had shoved it into my wallet before throwing me out of the house.

“You can go to a hotel, you can go wherever you want, but you’re not staying here,” she had said at first when I begged her to let me stay.

That was the first change in the plan. I wasn’t sure whether she’d known it all along or if it was something she’d decided on when Yonatan’s oximeter started to beep, as it had been doing every night for the past few weeks.

That night, after getting Yonatan ready for bed, we strayed from our usual dinner routine.

“I’m not hungry,” I told Ruchaleh, who sat, inanimate, on the couch.

“I want to sell the house,” she said, looking up at the ceiling. “I don’t want to be in this place anymore.”

We must have sat there in silence for something like an hour, until the gauge started to beep. That was my cue to run upstairs to the attic and connect the plastic contraption bulging out of Yonatan’s throat to the life-support system. Ruchaleh looked at me. I bowed my head and stayed seated. According to her plan, fifteen minutes would suffice. The beeping bounced off the walls, careened inside my head, pinged against the walls of my skull. I envisioned Yonatan gasping, choking, sputtering, his body convulsing, a shocked expression on his face.

“Where are you going?” she yelled, following me as I ran up the stairs. The oximeter, a small device clipped to his finger, beeped hysterically. I stood at the foot of the bed and stared at Yonatan. He looked exactly the same, lying there with the same placid expression on his face, no apparent convulsions or torment wracking his body. Ruchaleh walked over to her son’s side, to the oximeter, and turned down the volume of the beeping.

The plan was that she would wait fifteen minutes and then call an ambulance, pleading, panic-stricken, for a mobile ICU unit. “My son has stopped breathing.” That was her line. While she was on the phone, I was supposed to hook him up to the ventilator so that when the crew arrived they’d find him on life support, even though Ruchaleh said that the doctors wouldn’t be asking any unnecessary questions.

“Doctors tend to encourage end-of-life decisions on far less severe cases,” she said, “but who knows, with our luck, we could get some religious doctor and he could cause trouble.”

She was supposed to meet the ambulance crew outside. I was supposed to wait by the side of the bed. Ruchaleh said that an ICU doctor coming to the big house in Beit Hakerem, seeing Yonatan on his eggshell mattress, surrounded by the best life-support system money could buy, would probably issue a death certificate on the spot, without ordering an autopsy or any other kind of investigation. They’d probably skip the CPR, since he was on life support already, and just confirm his death, at which point she’d burst into tears.

“I just hope I’ll be able to pull it off,” she said.

When the doctor asked whether he should issue the death certificate, she’d dissolve in tears and send me to take care of it.

“By then,” she said, when the idea first came up, around a year earlier, “I hope you’ll have decided which ID card to give to the doctors.”

Ruchaleh said that our plan was virtually risk-free. We’ve already taken care of the tricky part, she said once – the identity change. We both preferred the words changeand updaterather than theftwhen speaking of Yonatan’s ID.

“It was written from above,” Ruchaleh said once. “You think it’s coincidence that your name is Amir Lahav, a kosher lemahadrinJewish name?”

My name, written out in Hebrew, really does sound totally Jewish, but in Arabic it’s different – Lahab—meaning flames. I remembered from a young age that whenever I went to the doctor’s office in Petach Tikva or to see my mother when she was in the hospital, Jews always got my name wrong. The way they pronounced it always made me laugh and I would tell my mother about their mistake. Later, as a teenager, it no longer bothered me and I was actually happy to have my name Hebraized, a phenomenon that saved me many a sideways glance. When I went to college the fact that my name could be read both ways turned into a real bonus: it’s how I wound up with a good dorm room at Hebrew University, near campus, unlike the Arabs, who, as freshmen, if they didn’t have connections, were housed in the notorious Eleph dorms on the Givat Ram campus. A day before school started, I discovered that my roommate was Jewish, an economics major, a freshman. He couldn’t keep the surprise off his face when I introduced myself and made a point of pronouncing my name properly, in Arabic.

“Where are you from?’ he asked, the way soldiers do.

“Jaljulia,” I said.

“Cool,” he said, and a moment later he went out for a smoke. Ten minutes later an administrator showed up. “There was a little bit of a misunderstanding here,” she said, explaining that university rules require that, barring written consent to the contrary, Jews and Arabs had to live in separate quarters.

“It’s fine with me,” I said.

“I see,” she said, consulting her clipboard. “I’ll be back in a bit.”

My Jewish roommate came back to the room a few minutes later and started packing up his things. “Bro, they got the living situation a little confused at the office,” he said before leaving.

My new roommate was an Arab from I’billin in the Galilee. I’ll never forget the expression on his face and the dance of joy he did when he came into the room. “They told me I was in Eleph. They sent me a letter – Eleph, it said – and here I am up on Mount Scopus,” he exclaimed. “My friends over at Eleph are going to die when they see this. A steam radiator, on campus. Do you know what Eleph looks like? It’s where they throw all the Arabs. Maybe they started letting Christians get rooms on Mount Scopus. Maybe that’s what happened. This is a miracle. I’m telling you, it’s the miracle of the Virgin Mary.” He kissed his cross, and frowned when he found out I was a Muslim, but he did not leave. “What does it matter – Muslim, Christian? At the end of the day it says Arab next to both of our names.”

Before leaving the house that night, Ruchaleh said, “I need one of the ID cards.” I took one out and gave it to her. The other one I put in my wallet. She opened up the little blue book, smiled, and tears started to well in her eyes. “Everything’s going to work out,” she said, and then she hugged me hard. “Go, go,” she said, “get out of here,” and she shut the door behind me.

GOLDSTAR

I want to be like them. That’s the sentence that was bouncing around my head as I followed Noa into the Ha’sira pub. She said “hey” to a few of the people there, exchanged kisses with a few others, introduced me to them. “Guys, this is Yonatan.”

She walked over to the DJ booth. The guy looked familiar. He slipped off his headphones and smiled at her, leaned over his turntables and his mixer, and kissed her on the cheek.

“Come here,” I read her lips as she motioned me over. “Meet Aviad,” she said. “He’s third-year, visual media.”

I shook his hand.

I want to be like them.

Noa asked what I wanted to drink and smiled when I said red wine, suggesting that I go with beer. I agreed. She preferred sitting at the bar, she said, but we took seats at a little wooden table in the corner because all the bar stools were taken. The DJ played some Radiohead and Noa moved her body to the music, saying that at this hour you could still enjoy the music.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“You’ll see,” she said.

The more the place filled up, the faster the music got. Aviad played some soft Underworld, then switched to Plastic Man and then back to faster tracks from Underworld. Noa was a better drinker than I was, but she always waited for me to catch up. I struggled to keep the pace, which she thought was funny. I could see that off to the side of the bar the tiny dance floor was starting to fill up, people moving their bodies gently in front of the DJ, not wanting to be the first ones to really dance. I volunteered to buy the third round, and took my place in the crush around the bar. Noa smiled at me each time someone pushed past me. She wanted to get up and come help me but I signaled to her to stay put and save our seats. I was finally able to get two pints of Goldstar and make it back to the table.

I want to be like them. That’s what I thought when Noa said this was the only place she liked to go out in this ghost town of a city. “The nerd-in-disguise hangout,” she said.

Most of the people looked like they were students and I recognized many of the faces from the halls of Bezalel. I’d never been in a place like that, and I liked it. I’d been out to pubs before with Ruchaleh, but they were the kind of places that had soft light and cool jazz, nothing like what was happening here. I had to stop myself from shivering when I thought of Ruchaleh. What was she doing at this moment? How did she feel? I should have been with her. I shouldn’t have left. If everything was going according to plan, then the ambulance should have already left with Yonatan and taken him to the morgue in Shaare Zedek. They don’t check anything there, Ruchaleh had said, it’s just a refrigerated storage room where they keep the merchandise until it’s picked up. Anyone who asked about the funeral would be told that Yonatan, without her even knowing, had decided back in high school to give his body to science.

“What?” Noa asked. I couldn’t hear her.

“Nothing,” I mumbled, and I tried to return to her, to the pub, the music. “L’chaim,” I said, raising my glass, and she raised hers. “L’chaim,” I said again as I brought the glass to my lips and tried to remember that legendary hero from before the days of Islam, a-Zir, who was infamous for his love of women and alcohol. On the night that his father, the head of the tribe, was murdered, they came to the drunk poet and told him the news, to which he said, a pitcher of wine in his hand, “ Ilyom hmar wa’ad amar.”Wine today, action tomorrow. The following day he embarked on one of the most brutal vengeance campaigns in the history of the Arabs.

Beer today, I said to myself and looked around. Today I want to be like them. Today I want to be one of them, to go into the places they’re allowed to go, to laugh the way they laugh, to drink without having to think about God. I want to be like them. Free, loose, full of dreams, able to think about love. Like them. Like those who started to fill the dance floor with the knowledge that it was theirs, they who felt no need to apologize for their existence, no need to hide their identity. Like them. Those who never looked for suspicious glances, whose loyalty was never questioned, whose acceptance was always taken for granted. Today I want to be like them without feeling like I’m committing a crime. I want to drink with them, dance with them, without feeling as though I’m trespassing in a foreign culture. To feel like I belong, without feeling guilty or disloyal. And what exactly was I being disloyal to?

“You coming?” Noa asked through the haze of house music.

“I don’t know how to dance,” I said.

She got out of her chair, leaned over the little table between us, and brought her mouth close to my ear.

“Neither do I,” she whispered, and I could feel her breath penetrating my ear, bringing me back to life.

PART SEVEN. HOT WATER

The lawyer couldn’t say definitively whether he was asleep or awake. He heard the morning noises of his wife and kids, as he did every morning, but they seemed to be coming from somewhere else, somewhere foreign and unfamiliar. He opened his eyes and hoped to see his daughter standing in front of him but she was not there. The lawyer tried, unsuccessfully, to put his mind in order, and then he gave up and went back to sleep. When he awoke again he wasn’t sure how much time had passed, seconds or hours, before the din of the house reached him again. This time he rose to a familiar world. He knew he was sleeping in a bed, in his daughter’s room, in his house, and he heard footfalls on the stairs, coming his way.

“You still sleeping?” his wife asked in a soft voice, laying a hand on his forehead to see if he had a fever. “You’re a little warm,” she said, even though the lawyer knew he wasn’t sick. All he was was tired, exhausted. He had started reading The Kreutzer Sonata,sure he would never get past the first line, but he had found himself drawn into the plot, which involved a train, a young man, a woman, talk of love, and a character who murdered his wife and starts to tell his story.

“Mommy,” his daughter said, her feet pattering behind her mother.

“I asked you to watch your brother for a second,” his wife said, raising her voice.

“I know,” the girl said. “But I’m tired, I don’t want to.”

“So?” his wife said to him. “What do you want to do? You want to take it easy at home a little today?”

“No,” he said, flipping the blanket off. “I have a hearing in court at eight thirty.”

“Mommy,” the girl said. “When are you going to brush my hair?”

“Give your hair a rest, okay? I’ll brush it in a minute. So, do you want me to make you some coffee before I go?”

“No, no,” the lawyer said, sitting on the edge of the bed and trying to limit his movements to the bare minimum so as to stave off the headache that had already announced itself. He looked over at the rabbit-shaped alarm clock and said, “You guys should get going. You’re late. I’ll head out after you.”

“Okay, take it easy,” his wife said and kissed him on the lips, a kiss the lawyer felt was genuine, not forced or apologetic or meant to conceal. “I really love you,” she said before leaving, and the lawyer gently nodded his head, to the extent that the headache allowed.

Water, first of all water, the lawyer thought as he walked up the stairs. He drank straight from the bottle, as he always did when no one was around. Then he called Tarik, who was on his way to the office. “I have a hearing on the Marzuk case at eight thirty. Please go down to the courthouse and ask for a continuance on account of illness. I’ll be in the office at nine. I have to take care of something first. Oh, and Tarik, we’re interviewing the new interns this afternoon and I may need you there. Could be you’ll be the only one there. Interview them yourself and choose yourself a bride at the same time, okay?” the lawyer said, laughing.

The lawyer made Turkish coffee and added milk and sugar. In the mornings he took his coffee with milk, which had an immediate effect on his bowels. He took the cup of coffee down to the study, lit a cigarette, and checked the Haaretzheadlines online. Then checked to make sure that he had everything he needed, realized that he had forgotten The Kreutzer Sonata,left the cigarette in the ashtray, and went to his daughter’s room to get it. He was on page thirty and had been using the note as a bookmark.

Mornings in Jerusalem are cold, even in summer, which is why the lawyer had a gas-operated water heater installed in the house, ensuring that the shower water was hot as soon as it was turned on. He found the right temperature and then stood beneath the wide veil of water cascading from the eight-inch shower head. He brushed his teeth, shaved his face, washed his hair. Looking up at the shower head, washing soap off his body, he was struck by a long-forgotten childhood memory. He saw his mother boiling water on a gas stove on a cold winter night and he saw his brothers, naked, freezing, and his mother approaching with a pot of warm water, ladling it over their heads with a brass cup, one at a time, and then scrubbing them hard, an expression of great suffering on her face. Her children had to be washed every day, they would go to school clean, even in winter, even if it meant suffering. When the boys were done they shared a single towel. Then came their little sister. His mother washed her in a little tub, supporting her neck with one hand and washing her with the other, shampooing the fine strands of baby hair.

There were a dozen white shirts hanging in the closet, all starched and ironed, each paired with a tie of his wife’s choosing. His pants were hanging on special hangers. He picked out a pair of black slacks, chose a shirt, placed a tie around his neck, and decided he’d tie it later. Putting on his shoes, he called Samah.

“Hi, Samah, good morning. I’m running a little late. Something came up. Yes, I know, I spoke with Tarik already. What else is on the agenda for today? Okay. I’ll be in by nine. Wait, just a second, that ID number you gave me yesterday, do you still have it on you? Yes, exactly, Amir Lahab. Send the number to our guy in the court system and ask him to find a current address, please. And tell him not to take his time this time. Be assertive with him. Tell him I don’t want to wait until tomorrow. Okay, great, can I bring you a cup of coffee? Oh, and Samah, do me a favor and keep this between us.”

The lawyer’s carefully laid plans began to go awry as soon as he got into his car and fielded a telephone call from his wife.

“Where are you?” he yelled toward the speakerphone.

“At work. I just wanted to see how you’re doing. Did you leave for work already?”

“Yes, sure, is everything okay? Is something wrong?”

“No,” she said. “Everything’s fine. I took the kids in, everything went smoothly. I’m heading into a meeting now and I won’t be able to use the phone so I figured I’d give you a call before it started, see if you decided to stay home.”

“No, no, I’m in the car.”

“You on the way to court?”

“Court?”

“You said you have a hearing at eight thirty, remember?”

“Oh, right, sure. I’m on my way to the district court,” he said, and immediately felt that she was checking to see whether he was tied up and if he might beat her to the punch and file first.

“Okay, so I’ll give you a call later?”

“Yeah, yeah, ’bye.”

The lawyer felt like he was choking. He cranked up the AC in the car and opened the window. Was it possible that his wife was smarter than he was? Craftier than he was? She had never before called him in the morning to see how he was doing, to find out where he was and whether he’d made it to court or not. He envisioned her standing outside the Israeli civil court for family matters, which opened at eight thirty, fully aware, as was he, that her financial future hung in the balance. “She’s never called me in the morning before,” the lawyer said out loud. “Never asked me about my fucking job. So why now? And the kiss? And the sweet talk in the morning? Since when does she touch my forehead to see if I’m running a fever?”

The lawyer, waiting in traffic, cursed the car ahead of him. He had to stop himself from leaning on the horn. Maybe she was just trying to soothe him. Maybe she was just shaken by the fact that he’d found the letter, maybe she was afraid he didn’t believe her? And with good reason. He imagined her laughing out loud, in a voice that wasn’t even hers.

“I just talked to him,” he heard her tell the man by her side. “He’s on the way to court, nothing to worry about. He bought the whole story, doesn’t suspect a thing.”

The lawyer tried to find a shortcut and turned off Hebron Way toward Talpiot. He wasn’t sure where to go – to family court, to catch her in the act? But what would he do then? Laugh? Cry? What would he do when she tossed him that scornful look, proud for having beaten him? She’d be safe there. What could he do to her in front of all those policemen and courthouse security guards.

And maybe the best thing was to simply go to the Sharia court this instant and file for divorce there. But that wouldn’t help either. If she was already at family court then it was over, the civil court system had jurisdiction. The lawyer decided to drive by her work to see if her car was parked outside. That way he could continue on with his plan. “Just a little wrinkle,” the lawyer mumbled to himself. “Just a little wrinkle.”

He replayed the brief conversation with his wife. What were the noises he’d heard in the background? He wasn’t sure. Was there that kind of din in the family court already at this hour? Did he even hear much noise? Actually it had been completely quiet. Was her office completely quiet? Where did she work on Sunday morning anyway? At the clinic? Or the office? What an idiot. What an ass he’d been all these years. He didn’t so much as have his wife’s number at the office. Now he knew why she always called the office and not his cell: so she’d know exactly where he was at any given moment. “No,” he’d heard her say, “it’s because I never know when you’re available.”

The lawyer tried calling her back on her cell. At the very least this time he would make a point of listening to the background noises. But what would he say? Would he ask her if she wanted to meet for lunch? That would be unprecedented. What would he ask her: Where are you working today? Why did he want to know that? The lawyer couldn’t come up with a convincing reason and, at any rate, she didn’t pick up. A meeting;the lawyer smiled and told himself he had married someone with a superior mind. The first thing he would do was look for her car outside the social services office in Talpiot. She went in to that office at least twice a week, of that he was certain. If not, then he’d go to that fucking mental health clinic of hers. And if he didn’t find her car there, either? Well. . He honked at the car in front of him.

CORPSE

Pushing the key into the lock, I hoped that nothing had changed. The weekend edition of the paper waited beside the door, wrapped in a plastic bag, covered in dew. I picked up the paper, shook off the drops, and opened the door.

Ruchaleh was on the couch, awake, looking terrible. Her eyes were puffy, her gaze was fixed on the ceiling, and there were two empty bottles of red wine on the table. The sun had risen but the blinds were still shut and the only light in the room came in from the kitchen. I said nothing. I stood in the entryway and waited for her to turn toward me. There was no need for me to go up to the attic. Something clearly had changed. Moving slowly, Ruchaleh turned and looked at me. Then, making a great effort, she smiled and moved her head up and down, again and again.

“Do me a favor,” she said, “and don’t stare at me with that pitying look.”

I froze, even though what I wanted to do was run to her and hug her and tell her that I loved her. I wouldn’t care if she said something like, I can’t stand histrionic people,or What a pathetic Arab.I wanted to fall into her arms, console her, be consoled, receive a warm hug, and hear her whisper in my ear, “Don’t worry, Mommy’s here,” in a voice that would soothe all my fears.

“What are you doing standing there like a golem?” she said. “It’s over, it’s done.”

“It’s just beginning,” I found myself saying, completely unsure of what I meant.

“I can’t stand,” she chuckled, and then she was quiet for a moment before adding, very softly, almost apologetically, “Come here, you little dunce.” I walked over to her and she hugged me harder than ever before and she wasn’t even taken aback when I lay my head on her chest. She hugged me as though I were hers, and I, on my knees, on the floor, burying my head in her chest, tightening my grip, tried to make myself more and more hers. I didn’t look up but I knew she was crying. She groaned in pain and her body shook. “What are you doing crying like a little kid?” she asked me in a wavering voice, stroking my hair. I knew she was silently saying, “Stay here, stay here with me.” I stayed until she fell asleep and only then did I break her embrace.

“ A’rib?” the man in charge of burials in Beit Safafa asked over the phone.

“ A’rib” I answered in Arabic. Stranger.

“So then it will be a small funeral,” he said.

“There will be no funeral,” I said.