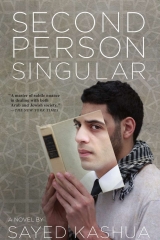

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

That was not a likely scenario. Maybe she’d have a different explanation. Perhaps Yonatan was a colleague who had asked her to translate the sentence into Arabic for him. Or maybe she had written it to someone else before the lawyer had met her. But the notion of her having an Arab boyfriend before they met made the lawyer wince and ruined his peace of mind. He breathed deeply and tried to remember all the conversations he’d had with his friends, in which he bragged how enlightened he was and how he would not mind marrying an Arab girl who’d been in a prior relationship. He even remembered exactly what he had said to his friends, most of whom had always said they would never marry a nonvirgin, even though some of them had spent years together with Arab girls whom they called girlfriends, but who were clearly only playthings because, as they said, she who had relinquished her honor once would relinquish it over and over again.

At the time he had disdained those friends, particularly because they hid the fact from their girlfriends, sometimes for years, that there would come a time that they would unceremoniously dump them. What are you going to do, they would say, we weren’t the ones who popped the cherry. But if she’d had a prior relationship, why hadn’t she told him? He would have forgiven her. But would I have? he wondered. Yes, if she had been straight with me, then yes. But she had not been. And what kind of relationship had it been? Had she slept with him and then had her hymen restored before the wedding? Had she faked the blood on their wedding night? And if she hadn’t slept with the other guy, what would he think? If all they did was kiss? Or hold hands? Or write each other love letters?

The lawyer shook himself free of those thoughts and tried to restore the calm he had felt when he learned that she had in fact gone to her friend’s house. He decided that when she came home he’d simply give her the note and see how she reacted, see if her explanation seemed plausible. After all, he knew his wife and he knew there was no way she had cheated on him. No way.

The lawyer put his cigarette out in the ashtray. He thought he heard a noise coming from the upper floor. He rolled his chair over to the door, opened it a crack, and listened. “Leila,” he said softly, but there was no response. She hadn’t come home yet. He considered taking a shower, perhaps even getting out before she made it home, but didn’t like leaving the kids alone, especially the little one. He could wake up at any second and start howling and no one would hear him. But mostly he didn’t want to miss the moment when his wife came home. More than anything else he wanted to see that smile, the one that would explain it all away, promising that everything was okay, that nothing had changed.

According to his calculations she should have been home already. But the lawyer figured that once she’d heard that he had picked up the kids she had decided it was all right to stick around at Diana’s, chatting a little more with her friends. He would not call her. He did not want to be one of those men that are always checking up on their wives and are stingy with their free time. She’d be home any minute. Even though he’d sworn he wasn’t going to look at the briefcase, the books, or the note, he couldn’t resist. Just the books, he told himself. The first was a book of drawings by an artist named Egon Schiele. The lawyer flipped through the book and looked at the crooked, distorted coal drawings of nudes. He went through it quickly and wondered if the artist was someone serious or just some unimportant fringe painter. How does one tell? The lawyer didn’t like the drawings much but he knew he didn’t know anything about art and as he browsed he felt a familiar ache. He Googled the artist and saw that he was an important figure. I wonder what Yonatan does for a living, he thought, and then tried to impose the artist’s name on his memory. Egon Schiele, Egon Schiele. Another scrap of information that could help him fill the glaring gaps in his education, especially in so far as art was concerned. He recalled how a colleague had once said to him in court, “Don’t tell me you don’t know who Chekhov was?” And that recollection led him to another earlier but no less painful one, from back in his college days, when a Jewish student had discovered that he had never heard of the Rolling Stones. He, of course, resorted to the technique he had learned from other Arab students, who employed it often, and responded with a question that was meant to underscore the cultural divide, “Why, how many Fairuz songs do you know? Do you have any idea what Al-Mutanabbi wrote?” And yet he had felt a sharp twinge of inferiority.

He looked at the signature on the first page of the art book again, Yonatan,and only then turned his attention to the other book. It was One Hundred Years of Solitude,by Gabriel García Márquez. The lawyer had heard of the author and the book. Maybe this was his chance to read it. He flipped through the pages. He stopped for a moment and made sure that the sounds he heard were not coming from the upper floor of the house and then looked at the signature again before closing the book. He went back to the Egon Schiele book and opened it to the signature page. Something didn’t add up. The same word was written in the same place, in a similar style, but the lawyer felt that the signatures were different. He left both books open to the signature page and took The Kreutzer Sonataout of his briefcase. The signature on that one was more like the one on One Hundred Years of Solitude.Those signatures were written in bigger letters and, though they were written with different pens, he was sure that they were identical. Something must have been bothering Yonatan when he penned his name in the Schiele book, the lawyer thought.

When he called his wife he hoped to hear the ring of her phone from just outside, but no one answered. She must be driving, he thought, or maybe she was really close to home. She never answered when she was nearby. Instead, she’d park and come into the house and say, “I was right outside when you called.” He looked out through the living room window. First toward the garage and then down the block, but saw no approaching lights. He decided to call again after he smoked a cigarette, but he called after two drags and got her answering machine again. This time he didn’t even put the phone down, just immediately redialed. Why wouldn’t she answer the phone, the whore. He exhaled in bursts and kept the telephone in his hand. He punched her number in again and again and kept getting her voicemail. The lawyer slammed his hand down on the table. He inhaled sharply on his cigarette and his chest began to constrict. Again he saw his wife frolicking in bed like one of those sluts in the movies, casting a sideways glance at her phone and ignoring his calls without any remorse. Or maybe she was sitting in the car he had bought her, and her lover, who now seemed to be the most manly of men, with wide shoulders and a chiseled face, was slipping his tongue into her willing mouth, and she playfully bit his lips and then licked her own. Her lover’s lips moved down to her neck and she stretched up toward him, arching her back and moaning as his lips reached her chest. He could see this lover sliding his hands under her dress. When the hell did she start wearing dresses anyway?

The lawyer knew he had to do something. He thought he might take the car and go out and look for her and beat the two of them to death. He was capable of that, he knew he was. No man, no matter how strong, could stop him now. But the lawyer couldn’t leave the kids alone.

He raced up the stairs, his heart pounding, hands balled up into a fists, fingernails digging into the skin of his palms. He knew she was late, knew there was no way she had stayed at her friend’s this long. Where could she have gone? And why wasn’t she answering the phone? He knew the answer. The lawyer went into the bedroom and opened her side of the closet. She had taken the better side, the one with more shelves and bigger drawers, the one with more space, and still she always complained that she didn’t have enough room for all her things. He shoved both hands into the closet and starting clearing the shelves, flinging her clothes to the floor. Pants, shirts, nightgowns, gym clothes, underwear, all of it landing in a pile on the floor. He pulled dresses and jackets off their hangers, yanked open drawers and shook them free of their contents but making sure to do it in silence so as not to wake up the baby in the crib. He stomped down to the kitchen to find scissors, there had to be scissors! The lawyer whipped open the kitchen drawers, which opened with a smooth European efficiency, and rifled through the implements, settling on the kitchen knife.

“What are you doing?” he heard her ask, and spun around.

“Where were you?”

“What’s wrong? What are you doing?”

The lawyer wanted to pummel her and yell at the top of his lungs, but he would not raise his voice, not if it meant the neighbors would know what was happening inside his house. So he shrieked softly, tightening every muscle in his body, “Where were you? Where?”

“What do you mean where was I? I was at Diana’s. What’s wrong? Is something wrong? You’re scaring me. Are the kids okay?”

“You’re a liar.”

“What? Why are you talking to me this way?” She’d never seen him act like this before. “What did I do?”

“You’re a liar. Why didn’t you answer the phone?”

“What? When did you call?” she said, bending down toward the bag she had already tossed on the floor. She pulled out the phone. “You called? I didn’t hear a thing. Look, my battery’s dead,” she said, showing him the phone.

“Stop lying and tell me where you were.”

“What do you want from me?” she said, bursting into tears. “I told you I was at Diana’s.” She covered her face with her hands and ran to the bedroom. The lawyer wasn’t buying her act. He ran after her. The pile of clothes on the floor added a decibel to her crying and the lawyer saw true fear in her face, the fear of a cornered animal.

“What is this? What happened?” she started backing away toward the wall, looking for shelter, fearing her husband as if he were some unknown creature.

“Why are you pretending to be scared? Just tell me where you were,” he said, and she just sobbed. She curled into herself and raised her hands to shield her face from an expected blow, even though the lawyer had never hit her. He looked over at the crib to make sure that his son was sleeping through this. Not being able to punch her in the face, to crack the cartilage of her nose, made him feel weak and lowly. Someone like her could interpret his behavior as helplessness.

“Who were you with? I want you to tell me who you were with.”

“What do you want from me?” And then more sobs.

“I know that you weren’t at your friend’s house,” the lawyer said, shifting tactics. For some reason he felt at ease and in charge. “So tell me where you were.”

She sobbed. “I swear I was at her house. Ask her.”

“I did,” the lawyer said coolly. “I called her and she said you left over an hour ago.” The lawyer turned to her, full of confidence. He hoped to see true bewilderment in her face, for her to accuse him, or Diana, of lying and for her to insist that he call her back this instant. But his wife did not react in that manner and a listless, melancholy feeling began to spread through him, replacing the rage of earlier, when she said, “I went out with Faten for coffee at Iskandinia. She wanted to discuss something about work. So what? So what?”

The lawyer saw her fear morph into defensiveness and he knew that he had lost. He walked slowly down to the study and lit a cigarette, but he couldn’t focus. He should have restrained himself, and now he hated himself for his impulsiveness. He had lost this battle, perhaps the war, but that wasn’t what was on his mind just then. Actually nothing was on his mind, because what did it matter if he got half their property or custody over the kids. He smoked leisurely and felt his heart rate relax. He did not respond when she knocked on the study door. She opened it and stood there with eyes swollen from crying. There was no trace of the earlier fear. He looked her way and then turned to watch the cigarette smoke curl out of the open window.

“Can you please tell me what all of that was about?” she asked. He kept his head down so that she wouldn’t see the failure on his face. “I’m sorry,” the lawyer said softly, then reached into his briefcase and handed her the note. He did not look at her and he did not expect an adequate response.

“What is this?” she asked after reading the note. “What is this thing?”

“I thought that was your handwriting.”

“Mine? No,” she said, shoving the note away, the way children do, thinking that once you’ve hidden the evidence it ceases to exist.

PART FOUR. FRIED SAUSAGES

For the first few weeks after quitting the outpatient clinic, I hardly ever got out of bed before noon. After the night shift with Yonatan I’d take the bus to Musrara and get hummus with fava beans at Akramawi’s hole in the wall and then take a share-taxi back to the apartment in Beit Hanina and crawl straight into bed. Majdi and Wassim were already at work so the place was empty and quiet. Sometimes I’d go straight to sleep and sometimes I’d read one of the books I’d borrowed from Yonatan’s library until my eyes closed. I’d wake up at some point, drink some water, go to the bathroom, and then crawl back into bed.

Wassim would come back at three in the afternoon. If he hadn’t eaten anything on the way home, we’d fry up some sausage and eggs or make some tuna and cream cheese and eat together. After that he’d rest for an hour before his evening shift at the hostel. Majdi, I barely saw.

I stopped sleeping during the night shift, remaining awake until Osnat showed up in the morning. Ever since I told her that I had left the social services job and that I didn’t mind if she came in a little late, she started showing up at eight in the morning. She was very happy with the new arrangement, even said that her husband was going to buy me a present because he wasn’t in charge of getting the kids off to school in the morning anymore. “We almost got divorced over it,” she said, laughing.

I spent the sleepless nights listening to music and reading Yonatan’s books. There were 156 books on the shelves and 98 CDs on the racks, 70 in English and 28 in Hebrew. Yonatan had written his name on the inside jacket of his discs, too. He had nice handwriting, very delicate, like a good student or a pretty girl.

On one of the top shelves he had a fine collection of hardcover art books. Most of them were photography-related. They looked old, filled with black-and-white photos. I looked through the photos occasionally, but mostly I was interested in the Hebrew fiction. I must have averaged a book every three shifts. Some I liked more than others, but I made a point of reading each one all the way through.

There was nothing for me in Jerusalem. I was an unemployed social worker. The night shift with Yonatan wasn’t really a job and the salary I got barely covered the rent for my little room in Beit Hanina. I knew I wouldn’t be able to spend much more time in this city, and each night I would decide that it was time to go back to the village, to my mother, but when the sun came up and the shift was over, I’d delay my return by another day. Sometimes I’d lean on the windowsill of the open attic window and take in giant gulps of fresh air, telling myself that everything would work out, that a new job was waiting for me right around the corner. After all, there was always a lack of social workers. I’d go to the social services’ main branch, show them my diploma, and ask for a position, this time in the western half of the city. I’d show them that my Hebrew was as good as any native speaker’s and I’d tell them that the problem with the outpatient clinic in the Arab part of town was my colleagues’ miserable work ethic. I’d speak disparagingly of Arabs and the Jewish interviewer would nod; he knew what went on down there. This guy came to social work as a calling, he’d think to himself, not like the rest of the Arabs who studied it just because it was the only department that they could get in to. Everyone knows that Arabs study a trade in university. Everyone knows they want to be doctors or lawyers or accountants or at least registered nurses, and that their fallback options are education and social work. The university application gives you six department options and the Arab applications are all identical. My application had also had medicine on top and education on the bottom.

Once I finish charming the interviewer from social services, I’ll go straight to the Mount Scopus dorms and knock on Leila’s door and apologize for disappearing. I’ll tell her everything I told the interviewer. She’ll definitely identify with what I have to say and will understand how disgusted I was with the outpatient clinic. She’s not like them, she’s different – for some reason I had the feeling that she must have put social work first on her application. I’ll tell her that I love her, that I’m starting my master’s, that I’ll definitely get a PhD and that it won’t take me long to become a professor. I have the grades. I’ll get a faculty position and be able to support her and she’ll be proud of me and won’t be ashamed to take me to her parents and their faces will shine when they learn that their daughter has snagged herself a professor. I’ll tell her that I’m rich, not me personally, but that my family owns lots of land, and that will not be a lie but a statement of fact. Her parents could ask anyone in the Triangle about my father’s family and they’d hear that they were the biggest landowners in the region. True, I’m not in contact with them, but I am a legal heir and any court of law would give me my father’s land. I am the only heir and I could be rich. All I have to do is demand what is rightfully mine. “How long will you sit around idly,” I have heard my mother say, over and over. “It’s your future, your land.”

Tomorrow – that was the conclusion I drew from all of those nighttime thoughts, not now, tomorrow. Tomorrow I’ll go to social services main branch. Tomorrow I’ll go home and start to wage my war against my family. Tomorrow I’ll launch the campaign to restore my mother’s pride. Tonight I’ll finish the chapter of this book I’m holding and then I’ll go back to the apartment to be alone.

PASSPORT PHOTO

I learned everything there was to know about Yonatan during those sleepless nights. I read every scrap of paper, every note, and every document that I found in the drawers.

Yonatan was born in 1979. Just like me. In his small, square ID photo he made a point of looking serious, not smiling, and in his eyes I saw a melancholic look that I interpreted as sixteen-year-old sincerity. Mother’s name: Ruchaleh. Father’s name: Yakov. Address: Same. Nationality: Jewish.

That was the first time I’d seen a Jew’s identity card. I had thought that the nationality article on the IDs was something only Arabs had, so they could be separated from the pack, but it turned out that Jews had to be categorized, too.

In one of the lower drawers there were drawings that looked like they might be relics from Yonatan’s kindergarten days. Blue, black, and red lines and a few attempts at circles. His report cards from first through twelfth grade, his class pictures. It was always fun looking for his face in the pictures and once I found it I’d look carefully at the other kids. They were all white and they almost all had European names, some of them Hebraized. Yonatan had gone to the local public school until sixth grade and then transferred to the elite Leyada School on the Givat Ram campus of Hebrew University. He had pretty much straight As all through school. I could see from the report cards that the Jews had a different system than we did. Instead of Arabic they had Hebrew and in third grade they started English; in junior high he took Jewish history and Bible instead of Koran. He also had art and computers, while in the village we had a few subjects that were not on Yonatan’s transcripts, like carpentry and metalwork and Islamic religious studies.

He went to the Jerusalem High School for the Arts and majored in photography. There were shoe boxes in some of the drawers with black-and-white photos and, based on his grades and the comments his teachers left on his work, it was clear that he had done exceptionally well. For his foreign language requirement, he took French.

On one of the top shelves in his closet I found a padded black case that looked like it might hold some kind of medical equipment. I got up on a chair and coaxed the box out. As I shimmied it free, I felt that Yonatan had turned his head and was watching me, as though he’d caught me in the act. But Yonatan was in the same position, face and eyes turned the other way, always away from me, especially when I went through his things and invaded his privacy. The case held Yonatan’s camera. A big camera, the kind journalists had, nothing like the little ones I’d seen at home. I put it on the table, sat with my back to Yonatan, and pulled the camera out of the main compartment. It was heavier than I expected. Alongside it, in their own compartments, were a few different lenses and a few rolls of film. I took one of the round lenses out of the case and tried to fit it onto the camera, cautiously, slowly, till I heard it click into place. I picked up the camera, looked through the viewfinder, and saw nothing but blackness. I checked the lens and saw that I hadn’t removed the cap, and then I looked back through the viewfinder and saw before me a blurry, out-of-focus world.

BLUE LIGHTER

That night, while watching Yonatan, I smoked my first cigarette. On the way from Beit Hanina to Beit Hakerem I stopped in at a little convenience store in Musrara and bought a pack of Marlboro Lights, which was what Majdi smoked. A few seconds later I went back in and asked for a lighter. The shopkeeper took out a clear blue one and sparked it to show me that it worked.

That afternoon Wassim had told me he had decided to go back to the village. He’d gotten a job as a special-ed teacher in a school near Jat and he’d decided to go home, get engaged, build a house alongside his parents, and get married.

“If I stay in the city I’ll never really be able to save up,” he said, and back home he’d have no expenditures at all. Majdi was staying in Jerusalem for the time being, but not in the same apartment. He said he’d rather rent a place in Wadi Joz or Sheikh Jarrah, as close as possible to the courthouse and the office.

“If you want,” Wassim said, “Majdi could find something that would work for both of you.”

I nodded and said nothing. I knew that if something didn’t give soon, I wouldn’t be able to afford the rent much longer. But the knowledge that in two weeks’ time I would no longer have a place didn’t bother me; on the contrary, it was calming, liberating. I knew I could always sleep on the sofa bed beside Yonatan.

I got to Yonatan’s an hour early. Osnat opened the door and told me that I was early and that she had finally talked to Ruchaleh about splitting the work into three shifts. She couldn’t go on not seeing her daughter from seven in the morning until seven at night.

“We’re just going to have to find one more caretaker, Yonatan,” she said, caressing his hair before leaving.

I sat on the windowsill in front of the open window and took out a cigarette. I put it between my lips and lit it with the blue lighter. The cigarette went out. I lit it again, and again it went out. I didn’t understand how Majdi and the rest of the smokers in the world managed to burn a cigarette into ash. My first one was just blackened.

I rotated Yonatan in his bed and returned to The Notebook,which I had started the night before. The book was about twin brothers whose mother hides them in their grandmother’s small village during the Second World War. I was completely drawn in by the novel. It was one of the best I’d read and I knew that the night would fly by. The problem was that the book was too thin, too short, and even though I tried to read it as slowly as possible, I finished it within two hours. I rotated Yonatan again and then tried my luck with the cigarettes. I was sure the nights would be easier if I smoked.

I put another cigarette in my mouth and brought the flame close to the tip and when it touched the paper and tobacco, I inhaled deeply. This time it worked and I started to choke. I smothered my cough and felt my eyes water and threaten to pop out of their sockets. I ran into the bathroom, shut the door, and coughed hard until I was able to breathe normally again. I came out of the bathroom with my face washed and saw Ruchaleh waiting for me by the door.

“Is everything okay?” she asked, looking up at the ceiling and then directly at me.

I froze. She did not usually come up to the attic at night.

“Yes, everything’s fine,” I said.

“I don’t want you smoking next to Yonatan,” she said. “Not in the room.”

“I, I’m, ah. .” I stammered, “I’m not really smoking, I mean I. .”

“Doesn’t matter,” she said. “If you want to smoke just go outside to the garden or come down to the living room or the kitchen.” She shut the door behind her and left.

My face was flushed with shame and my attempts to smother another cough. I stood by the window and tried to breathe regularly, gingerly at first and then heartily, taking pleasure in the clean air now being drawn into my lungs. What did she mean, you can smoke in the living room? Where would she be while I was smoking in the living room? What was I supposed to do, go down there and smoke with her? I thought of how she never even really looked at Yonatan. She treated him as though he were transparent, looking over, under, and through him. What did she care if I smoked in his room or not? How was it that she was never by his side, that she preferred to spend money on round-the-clock care so that she didn’t have to spend any time with him.

It was a little past midnight and I was not having any luck putting myself to sleep. I opened Yonatan’s closet and carefully took out the camera. Soon enough I was able to click the lens into place. I looked through the viewfinder and tried to bring the items in the room into focus. When I spotted Yonatan, lying in bed with his back to me, I hit the shutter release and heard it click. The noise scared me. What the hell did I do that for? I looked at the door, waited for Ruchaleh to storm in and throw me out of the house. I quickly took off the lens, laid it back in the case, put the whole thing in the closet, sat down on the sofa, and listened to a long and undisturbed silence.

I tried to start another book, I counted cars passing below, and I listened to one of his Ministry albums twice, but it was still only three in the morning. I have to change my sleeping patterns, I thought. I have to be active during the days and sleep at night. It must be easier to be up during the day than at night. The thoughts that come and assault you during the day seem gentler and less scary than the ones that come at night. What’s the big deal? Why am I not allowed to use the camera and yet allowed to read the books and use the bathroom?

I turned my attention back to the camera and tried convincing myself that there was nothing wrong with what I was doing. Let Ruchaleh come in, who cares? She should be thankful that I’m here doing her job, taking care of her kid for her. She should be grateful that for a few nickels and dimes I come here every night, all night, and that I always come on time, even early. I looked through the viewfinder again, this time toward the street, the Jerusalem landscape at night, and pushed the button. There was no click. I looked at the camera. A little knob showed the number 22 and I realized that that was probably the number of pictures that had been taken. But I’d only taken one, so someone had used this camera before me. I hit the button again, without pointing the camera anywhere in particular, but it did not respond. I remembered that with our old camera at home you had to turn a little plastic wheel each time you took a picture, but there was nothing like that on Yonatan’s camera. I touched all the buttons and in the end decided to pull a lever alongside the knob. I heard the film advance and saw the number 23 on the knob. I pushed the button again and this time it clicked. I pointed the camera at the bookshelf, brought it into focus, and shot. Then I did that again and again until I hit 36 and could no longer pull the lever.

BUS PASS

I didn’t have much to move. The schoolwork, the folders, and all my papers went into the big garbage can outside our apartment building in Beit Hanina. The clothes came with me. I took them little by little in my gym bag, each day another installment, straight up to the attic in Beit Hakerem. I made some room for my things on the top shelf of Yonatan’s closet, up above the camera. I had to stand on a chair to reach my stuff. Within a week all my clothes were in Yonatan’s room. It was embarrassing to see how little I had when compared to the wardrobe of the immobile man I cared for.

At the end of the month, Wassim left the city and moved back to his hometown village and Majdi moved into a place in Wadi Joz along with another lawyer. I was left with no place of my own, but with a pull-out sofa alongside Yonatan’s egg mattress. At first I tried forcing myself to get some sleep during the night shift, knowing that I had no bed to sleep on during the day. I told Osnat that as far as I was concerned she could show up at ten, but she said that would be unprofessional.

I bought a monthly bus pass and spent a lot of the time going from bus to bus, equipped with Yonatan’s Discman and the CDs I chose each morning. They were my company until the next shift.