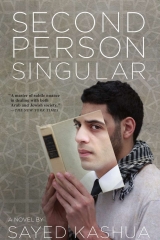

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

They can both go to hell, the two of them and the guy with the frozen gaze. Tonight is the night I bail. I’ll call Osnat from the central bus station and tell her I’m leaving Jerusalem and then hang up. She could shove it. Neither she nor Ruchaleh would come looking for me. Why would they? What good would they get out of it? I hadn’t violated any agreement, there was no contract, and they couldn’t demand anything of me just as I wasn’t demanding anything of them. Unlike Osnat, I had no benefits – no sick days, no vacations, no worker’s insurance. Nothing. A defenseless day laborer. Just as they could boot me out whenever they saw fit so, too, could I leave whenever I felt like it. They’d find another Arab to take my place. He’d be happy to have the job, no questions asked. Same goes for the café owner. I wouldn’t even call him. Screw him and the way he talked about the kitchen workers behind their backs, patting them on the shoulders and then talking about them like scum. So proud of the few words he knew in Arabic, the greetings and the curses, which he used as if they were a joke, waxing on about the techniques he’d developed to tame his Arab workers to make them follow his commands.

“You have to constantly remind them who’s boss,” he told me once, letting me in on the tricks of his trade. “If you let your guard down even the littlest bit, they’ll eat you alive.”

During one of those days, while I was bracing myself for arrest and planning my escape from Jerusalem, I heard a girl’s voice call me from behind. I had just finished up at the café and was on my way to the bus stop on King George Street. I didn’t turn around. “Yonatan,” she called again, this time from closer. I turned around, scared, and I saw number six smiling at me and plucking little earphones out of her ears.

“You don’t remember me?”

“I do,” I said. “Number six.”

“Noa,” she said, shaking my hand. The soft touch of her long fingers in my palm made me withdraw my hand quickly.

“You looking for an apartment?”

“No, I live here.”

“Oh, you’re a Jerusalemite?”

“Yes,” I said. “I work over at the café down the block. What about you?”

“I don’t know the area at all. And I don’t really understand what a school like Bezalel is doing in the middle of this city. Just the thought of four years in this place weirds me out.”

“You’re looking for an apartment?”

“Yes, I’ve been to this fucking city every day. Sorry. I must have seen five or six places already, but you have no idea what kind of rat holes they rent around here for five hundred dollars!”

“I know. The prices are crazy.”

“I found something nice today, though. In Nachlaot. I figure if it’s going to be Jerusalem, I might as well go all the way.”

“Yeah, all the Bezalel students live there.”

“This goes to the central bus station, right?” she asked, pointing with her chin toward an approaching bus.

“Yes,” I said.

“Good seeing you. I’ll see you in school, right?”

“I didn’t get in.”

“What?” she yelled, and I heard her say, “No way!” as the bus closed its doors.

I’m glad that just happened, I thought as I waited for the bus to Beit Hakerem. I’m glad it happened now. I needed that wake-up call, that smack in the face from Bezalel. I am a social worker, with a degree from Hebrew University, with good grades and the ability to get a good job. Why have I been wasting my time with photography? Why have I been wasting my time in an attic redolent of medicine and excrement?

LETTER

I fed Yonatan, brushed his teeth, changed his diaper, put him in his pajamas, moisturized his hands and feet, and got him ready for bed. I’d put my escape off until tomorrow. In the morning, I thought to myself, tomorrow morning, as soon as Osnat shows up, I’ll tell her that I’m leaving. I won’t even demand my salary for the days I worked in August. I’ll just disappear.

When Yonatan’s eyes closed, I took down the camera from the top shelf. I hadn’t taken a single shot since that cursed day when I went to the Bezalel interview. During the six months before that, I had shot about half a roll a day, about three rolls a week, but since that day, nothing. The thrill was gone. During the first week after the interview I still kept the camera slung over my shoulder, but after that I put it back in the closet. Now I took off the lens and looked through it, aiming at the farthest point of light outside the window, then I turned it toward Yonatan and tried to focus on his half-closed eyes.

I almost dropped the camera when I heard knocking on the attic door. “Just a second,” I yelled as I stuffed the camera back in its box and up on the shelf. I tried catching my breath as I opened the door. I didn’t know that Ruchaleh was home. Ordinarily I kept very close tabs on what was happening on the floor below me, listening to the jingle of keys as she returned home, following her steps and the sound of the keys hitting the wood of the dining room table. The faucet, the opening of the fridge, the bottles, the clink of the plates, the lights. I could always tell when she was in the living room and when she was in the bedroom. That night, maybe because she had come home earlier, while I was still in the bathroom with Yonatan, I hadn’t heard her come in.

“I think someone meant to send this to you,” she said, handing me an envelope and then leaving, shutting the attic door behind her. It was from Bezalel. I recognized the logo on the front of the envelope, next to the sticker that bore my name, which is to say Yonatan’s, and the address of the house in Beit Hakerem.

“I’m really sorry,” I said to Ruchaleh. She was sitting on the couch in the living room reading a book. I had never before started a conversation with her, but it was clear that she knew I had been using her son’s identity. She had not opened the envelope.

“I didn’t mean to,” I said, begging her forgiveness, avoiding her eyes. “I really don’t know what came over me.”

“Sit down,” she said, but I remained standing, eyes downcast.

“Again,” I said, “I’m really sorry, ma’am. It was just a game. I really don’t know why I decided to write your son’s name down and not my own.” I really didn’t know if the whole thing had happened because Yonatan had been a photographer or because the camera belonged to him or because I had learned everything I knew from his books, his pictures. Maybe it was just a game, I don’t know. But when I was taking photographs I was someone else, someone unfamiliar, foreign. Holding the camera in my hand I felt like an extension of Yonatan or the continuation of what he had been. I didn’t tell her about the post office box or the café or the bank account. She might not understand.

“Ma’am. .” I started.

“Don’t ma’am me,” she said. “Sit down. And don’t give me this I’m-an-obedient-little-Arab routine.” No one had ever called me a little Arab before or spoken to me in that tone.

“You’re insulted?” she asked. “Good, I’m glad. Now do me a favor and do yourself a favor and don’t talk to me in that groveling slave-at-the-master’s-house tone. And sit down already.” I sat before her, prepared to fling one of her books in her face. I’m not apologizing anymore. Let her call the police for all I care. I’m not scared of her or of anything else in this world.

“Listen to me, ma’am,” I said, this time in a gruff tone. “I know I did something wrong, something that I can’t even explain to myself at this point. But I don’t intend to study photography using your son’s name and I had no good reason to apply as him. As you know, I have a Bagrut certificate and a BSW and my chances of getting into Bezalel, if I really wanted to go there, were far better if I’d applied as an Arab.”

“Yes,” she chuckled, “I’m familiar with Bezalel’s system. They take every Arab that applies. Maybe that’s what led you to apply with a Jewish name?”

“No, not that.”

“Then why? I can understand the desire to want to be judged for who you are and what you’ve done and not your nationality or your ethnicity. That’s a very reasonable thing to do.”

“I don’t think that’s why.”

“No? You applied with a Jewish name, an Ashkenazi one, the kind that has no chance at affirmative action. I think you probably didn’t want to feel like someone was doing you a favor.”

“I don’t really know why I did it,” I said again, realizing that she wasn’t interested in chastising me or charging me with an offense. “Maybe it was because I knew that Yonatan wanted to go there,” I said without thinking, and I saw her expression change. Perhaps only now was she realizing that I had been looking through all of his things.

“I know,” she said.

“I’m really, really sorry. I didn’t mean to offend you.”

“You didn’t,” she said, and then added, “Well, don’t leave us hanging.”

“What do you mean?”

“The letter,” she said. “What does it say? Did you get in?”

PART FIVE. TRANCE

The lawyer leaned against the wall and tried not to collapse onto the filthy tiles of the bathroom floor. The thump of the speakers pounded his eardrums. Feeling like someone on the deck of a bucking ship, he tried to take a deep breath and scatter the collage of nauseating images. He leaned against the wall, legs weak and untrustworthy, and stuck his hand out for some toilet paper but felt only metal. Looking out of the corner of his eye, which took considerable effort, he saw that there was no toilet paper to be had. There was a thick roll of paper towels on top of the toilet and he spread his legs out, anchoring himself on the wet, filthy floor, and reached for them. He palmed the wall behind the toilet as he reached forward and in that way managed not to fall. Once he felt his body was adequately prepared, he let go of the wall and, with the sleight of hand known only to three-card monte players and expert pickpockets, snatched the roll of paper. He ripped off a big piece, put it on the floor near the toilet and with his foot began mopping away some of the mud and grime. Placing more paper on the floor, he felt a wave of relief as he dropped to his knees in front of the toilet. He wrapped a long length of paper around his hands, fashioning a pair of paper mittens, and held on to the sides of the toilet bowl as he brought his face close to the foul water at the bottom. He thought he could see the shimmering reflection of his face.

The main door to the bathroom opened and a blast of awful techno music burst in and was promptly muffled by the closing of the door.

“Come on,” he heard someone say, banging on the door, “how long you going to be in there?” This meant he’d have to wait again, until the man gave up and went back outside, because the lawyer did not want anyone to hear him vomit.

As soon as he left the house, the lawyer felt he had made a mistake. Leaving his crying wife in the room as she retrieved her clothes from the floor, he stood outside the door for a moment. She had asked where he was going, asked him not to leave, repeated again and again that she had no idea what was going on, begged that he explain it all to her, but he had taken his attaché case and left without saying a word. He had to show her that he meant business. She had to understand that something had been broken. But as soon as he left the house, he wanted to return, and if she had come out after him maybe he would have gone back in. All the lawyer really wanted was to have his old life back again and he tried to find a reasonable explanation for her actions, something that would set his mind at ease, something he could live with. He refused to believe the worst and began thinking of possible alibis for her.

Starting up the car, he hoped she would not flee. The lawyer was scared that when he came back home, in an hour or two, he’d find that she was no longer there. That she’d taken the kids and some clothes and gone to her parents’ house. Maybe her lover would drive them. Now that she knew her illicit love had been exposed, what was to stop her from calling her lover? Maybe that’s exactly what she was doing at this moment, talking to him on the phone, bawling, but also reveling in the drama, feeling like her life had finally started to look like those Egyptian, Syrian, and Lebanese soap operas she loved. And he – being just as stupid as she – would speak the kinds of syrupy words that were supposed to calm her, promising to take care of her, to watch out for her, to lay his life down on the line for her. Let her go off with whoever she wants, the lawyer said to himself, wondering about the complex character of this lover who was learned in art and literature and Egyptian sap.

Before even pulling out of the garage, the lawyer called his wife. Not to talk, but to make sure that her line was not busy. He let it ring twice and hung up. It wasn’t busy. Then he thought she might be talking to her lover on the landline and he called that number, too, waited for it to ring once, then hung up and pulled out. She called right back, undoubtedly having seen his missed call. But he, of course, did not answer.

He drove slowly and tried to piece together the chain of events. The moment she came home, the look on her face when she told him about the battery on her phone. Had she planned everything? Was she that devious? He’d known her for seven years and had never noticed anything that would lead him to believe that she could plot her steps so cunningly. He recalled social events that she attended alone, parties she had said were work-related, visits to friends’ houses. Those were a weekly occurrence. But prior to the discovery of her love letter, the lawyer had never suspected they were anything beyond social calls. Maybe she really was telling the truth. Maybe the battery really had died and maybe she really had gone out with Faten for a cup of coffee and some gossip, as they often did?

The lawyer breathed deeply before dialing Faten’s number. It wasn’t late at night and he knew he could call the accountant’s house.

“Hello,” Faten answered. There was a trace of surprise in her voice, not on account of the hour or the identity of the caller, but because hardly anyone besides unsolicited callers used the landlines these days.

“Good evening,” the lawyer said, trying to make sure his voice didn’t waver.

“Good evening,” Faten said, her voice more playful.

“So that’s how it is, ah?” he said, trying to keep his voice as light and friendly as possible. “The two of you leave us at home and go out to cafés?” His heart was pounding.

“Half an hour is too much for you guys?” Faten said playfully and the lawyer’s body melted with relief.

“Who is it?” he heard Anton ask.

“Hold on a second. I’m putting Anton on,” she said, passing the phone to her husband.

The lawyer had to come up with something. “I was thinking that if the girls can go out for coffee, maybe we could do the same. What are your thoughts on a beer at the Ambassador?” he said, praying that Anton would refuse.

“I wish,” Anton said, “I just came home now with the kids. I took them out to eat. My dear wife is so busy she didn’t have time to make anything.”

“I knew I couldn’t count on you,” the lawyer said. “Never mind, we’ll do it next time. Yallah,good night.”

So she did meet up with Faten. There was no way she would ask one of her friends to lie on her behalf. The lawyer nearly turned his car around and went home, but he still couldn’t come up with a good explanation as to why she had lied about the letter. He drove out of the village and onto the wider streets of the main road, the one that had once linked Jerusalem and Bethlehem. He called Tarik and then realized that Tarik was actually the only person he wanted to see that night. The lawyer knew Tarik would not refuse. He detected a note of happiness in the young lawyer’s voice when he asked him, over the noise of Tarik’s television, “So, where do you usually go to drink?” Once they’d decided the where and the when, the lawyer hit the gas and flew through the empty streets, trying to remember just when it was that the gates to Bethlehem had been locked.

THE FUTON

The lawyer opened his eyes and was saddened by the fact that he’d lost the ability to cry. He wanted to go back to the village, to his parents’ house, his real home, not the rentals he’d lived in in Jerusalem and not the house he owned in Beit Safafa, which he had never called home, as though he had been doing nothing but sojourning in the city. He wanted to go back to his old room, the cold room he had shared with his three brothers, the thin mattress and the sheepskin that his mother would put under it for insulation during the winter. He missed the crispness of morning, the walk to school bursting with confidence, the knowledge that his homework was perfect and that it had been written out in elegant handwriting, the kind that made his parents proud. Too bad he hadn’t gone back to the village after school, too bad he hadn’t listened to his father, who begged him to return home.

The lawyer’s eyes fluttered open and then closed again. Lying in Tarik’s bedroom, he drifted in and out of sleep and thought that the first thing he would do when he gained control of his consciousness would be to send Tarik home, to his village. If it comes down to it, I’ll fire him, and make sure no lawyer in the city takes him on. He was sorry he had stood in Tarik’s way, that he’d convinced him to stay in the city and not go home, and he knew he’d done it in order to prove to himself that he had not been mistaken, that he’d been right to stay in Jerusalem. The lawyer recalled that Tarik had driven him in the lawyer’s car after the long night of drinking and that he’d wanted to take the lawyer back to his house but that he had refused. He did not recall how it happened that Tarik had given him his bed, but he imagined that the young lawyer had insisted that his boss take it, saying that he would sleep on the couch in the hall.

The lawyer’s throat felt sandy, his head striped with pain. Specific memories of the night dissolved in a murk of shame. He knew he had acted like a complete fool. He had drunk like he never had before and it was very likely he had embarrassed himself like never before, too. Certainly he’d never exposed Tarik to this kind of behavior. But what most concerned him was whether he had let anything slip about his wife’s letter, her lies, the book, and the real reason he had not wanted to go back to his house. The lawyer tried hard to remember the night, and he was able to summon many things, fragments and entire conversations from earlier in the evening, and he was pretty sure he had not said anything specific about his wife, and so he was inclined to let himself off the hook. He remembered picking Tarik up at his house and driving to a pub called Ha’sira and that Tarik had said it was his favorite place on the western side of the city. He also remembered how surprised he had been and the way he had laughed when Tarik led him into the place, which looked less like a nightspot and more like a storage room that stank of beer, sweat, and cigarettes.

Tarik had apologized and said, “I warned you. I told you it wasn’t your style.”

Tarik had suggested going to a different place, “somewhere a little cleaner,” but the lawyer insisted on staying. They sat in the corner, around a heavy wood table near the little square of a dance floor, which was still empty because it wasn’t yet ten, and started off the evening with two pints of Taybeh. Tarik said that Ha’sira, the Boat, was one of the strongholds of the young Jerusalem left-wing crowd, and that most of the patrons were students at the city’s art schools – Bezalel, Nissan Nativ, and Sam Spiegel. They sold Palestinian beer on principle.

“Arab students come here, too.” He said. “Not many, but they come.”

“Arab girls, too?” the lawyer remembered asking, and Tarik had nodded.

“Yeah, not a lot, but some,” Tarik said, turning his head toward the door and the young couple that had just entered.

“Looking for someone?” the lawyer asked, smiling at his friend.

“Not sure,” Tarik said, and it seemed to the lawyer like he was a little embarrassed by the question, since the two of them had never before discussed personal affairs. But personal affairs were all that mattered to the lawyer at this point and that was why he had called Tarik. He felt blind, or like a deaf man at a loud wedding, as the Arab saying goes, and he wanted to know what it was like for young Arabs these days, especially the girls, what had changed since his days in university. Even then he had felt that a new, accursed wind of sexual freedom was blowing through the campus. The lawyer never partook in any of that, had never slept with an Arab girl other than his wife, even though the university was seemingly beyond the reach of parental and societal restraints, a place where different rules applied and he could have done as he pleased. There was an unwritten rule on campus whereby what happened on campus stayed on campus, and as soon as school was over all was forgotten and returned to its earlier state.

The pub began to fill up and the lawyer got them each another beer and offered to buy them a round of fine whiskey, but the pub did not have anything that matched that definition. There were no single malts, no malt whiskey at all, and the two of them had to make do with Johnnie Walker Red.

After the whiskey the lawyer asked Tarik what he thought of marrying a girl who’d had previous sexual partners, and Tarik had responded with a shrug, “I don’t have any problem with it.”

“I used to think the same way,” the lawyer said.

“And then what happened?” Tarik asked.

“I don’t know. I really don’t know what I think these days.”

“You know what,” Tarik said, draining his whiskey and seeming on the verge of a proclamation. “Not only do I not have a problem marrying a nonvirgin, I have a serious problem marrying a girl who is one.”

“What do you mean?” the lawyer asked, trying to smile encouragingly at Tarik.

“I want to marry an Arab girl who, for all I care, has fucked half the guys in the city. But only of her own free will. Someone who has used those Arab boys for her own means, slept with them and then dumped them. A wild girl, that’s what I want. That way I’ll know she picked me because she wanted me and not because it was the best of the choices she was offered or because I was the most socially acceptable option. I want to know that this girl chose me after rejecting all the other options.”

The lawyer, lying in Tarik’s bed now, deep under his comforter, didn’t attach much significance to what Tarik had said. He’d been able to say those things because there was nothing serious in the works, but he knew his parents would hang him by the balls if he did anything that tainted their honor. He remembered also that he had continued to drink whiskey while Tarik had made do with beer. At some point the pub had filled up entirely and everyone there seemed young and attractive to the lawyer. It was around then that his inhibitions drifted off entirely and he became convinced that he was as young and beautiful as they were, and with that knowledge he sauntered onto the dance floor. With all of his heart and soul the lawyer wanted to get a girl. Acting on information he’d amassed while watching television, he knew that the key was in the eyes, and with several long glances he told the girls around him exactly what he was after. On this night he would do what he had never before done. He would cheat on his wife. He’d take whichever woman fell for him to the most expensive hotel in the city. To the King David.

He looked at the women dancing nearby and got to thinking about how he’d find the perfect one, smart and beautiful and full of life, and already he began planning their lives together. He’d divorce his wife, and no one would say it was because she had an illicit affair. They’d say he was a creep, a skirt chaser, and they’d talk about how he had run off with a girl ten years younger than him. Yes, that’s what he would do, that would be respectable. And if she was the kind of young and bold Arab girl Tarik had talked about, all the better. A girl who’d fucked around, who’d used Arab men like socks, trying them on and tossing them aside. The important thing was that she not lie, he thought, that she be forthright.

None of the girls around him seemed like the type he was looking for and he waited for her to come through the door and for her to realize at first sight that he was the one, and for her to choose to come dance with him, to choose to get into bed with him, to choose to sleep with him, and he would be an amazing lover, using his trick – lying on top of her, or perhaps the other way around – recalling each and every check he had deposited that month, moving in and out of her as he worked out all of the bank charges, the VAT and the payments to the income tax authorities. And the next morning, when she told him he was the one and only, his friends would be stunned and jealous, especially his wife, the whore. He continued to look around at the girls, feeling he had found what he was looking for and then changing his mind, until he realized that his stares were not being well-received. He remembered now how his confidence had crumbled and how disgust and humiliation had taken its place and how his rooster dance had turned into a tremor in his knees. It was then that he felt his way to the bathroom to vomit his guts out.

The lawyer moved his head left and right and saw his pants and shirt on the chair in Tarik’s room, alongside the big futon. He jumped out of bed, clad only in his boxers, and his head spun. His leather attaché case was on the chair, too, and he opened it and looked for his phone while making sure not to let his eyes rest on the book or the rest of the evidence. The screen on the phone said that the time was eight in the morning and that he had missed twenty calls, all from his wife. The last one had been made just after two in the morning. The notion that she had been worried was comforting, but the comfort soon turned to fear when he wondered where the calls had been made from and whether she had gone back to her parents’ house. Maybe it wasn’t concern or remorse that had driven her to call but rather the urge to let him know that she had taken the kids and left, and that she just wanted to let him know that she did not want to see him again and that she thought he was a nothing, always had. Maybe she wanted to say that she had been an idiot, spending her best years with a creep like him, that he made her sick, or maybe she’d just hit him over the head with the truth, tell him about her true love, her unblemished lover, his support and devotion. Now that she held all the cards, she could tell him whatever she wanted. What a mistake he had made, the lawyer thought; he, the cold and calculating lawyer, had thrown half his net worth away in one moment of recklessness. By letting his guard down for one moment he had robbed himself of the chance to leave her penniless, to strip her of everything she had, to take away the children. All he had to do was wait one more day, until Sunday, when the Sharia courts opened, and file for divorce. His only hope was to get up and wait outside the Sharia courts and file for divorce before she made it to the civil court. But she had surely already consulted with her parents and family and was certainly at this very moment seated before some lowly lawyer from the Galilee with a crude accent and together they were, at this moment, wording her plea. Who knew what she might accuse him of? For a moment he really was curious about the nature of her accusations. Perhaps verbal violence, neglect of the children, oppressiveness toward her; perhaps even a charge of physical violence. The closet incident of last night would surely loom large in her allegations, along with jealousy, feverish suspicion, and baseless accusations.

The lawyer fished around in his pants pocket for a cigarette. His head was still spinning and he was thirsty. But he did not leave the bedroom because he knew that outside, in the hall, Tarik was asleep on the couch and he didn’t want to wake him up this early. He’d done more than enough by giving up his bed and who knew what kind of things he’d endured while hauling his boss up the stairs. The lawyer hoped that at least he had not been noisy and that none of the neighbors had woken up. He opened the bedroom window and saw that the view was of a neighbor’s balcony and that there was an old man sitting out there smoking a cigarette and having a cup of coffee. The neighbor was looking back at the lawyer. The lawyer snapped the curtain closed and pushed his legs into his pants and his arms into his shirt. As he buttoned his pants, he heard the harsh ring of a doorbell. After a moment of silence he heard the hoarse doorbell again, followed by Tarik, who, just woken, grumbled, “Just a second,” and then a confused “Who is it?”

The lawyer went to the bedroom door and practically put his ear to the wood in his attempt to hear what was going on. The key turned in the lock, the door creaked, and then he heard his wife.

“Good morning, Tarik, where’s the man of the hour?”

The lawyer was about to get up and greet her when he got his bearings back and sat down on the edge of the bed and shoved the extinguished cigarette between his lips, assuming a foul expression. Soon enough there were soft knocks on the bedroom door, followed by a gentle swiveling of the doorknob. His wife stood before him, smiling, and he could tell that she was going out of her way to keep the smile fixed on her face.

“Well, well,” she said to Tarik. “Here’s our man, all dressed and awake.”

The lawyer was silent, and Tarik, who stood somewhere in the hall, called out a “Good morning.”

“Good morning, Tarik,” the lawyer said, “could you do me a favor and get me a glass of water, please?”

His wife remained next to the door, fighting back tears, staring at her husband. How attractive she was now. He wanted to take her by the hand, pull her over to the bed, rip off her clothes, kiss her neck, feel her writhe beneath him on the hard futon. Don’t give in, he reminded himself, you have a plan and you have to stick to it. Don’t be weak; don’t let her control you. Don’t let her sad eyes trick you. Remember, he told himself, this is war and your adversary is a woman that you hardly even know.