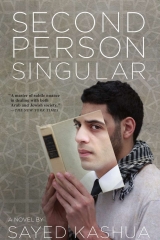

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

“You have permission for burial?”

“Yes, I got it from the hospital.”

“You know where to bring him?”

“No.”

“You know the small mosque near the cemetery?”

“I’ll ask.”

“Okay, bring him there,” he said. “Ask anyone in the village and he’ll direct you there. Everyone knows where the cemetery is.”

“Okay, thank you very much.”

“Allah Yirachmo,” God have mercy,said the man to whom death was a livelihood.

Equipped with the signed certificate of death and the ID card, I set out in Ruchaleh’s car for the morgue at Shaare Zedek, where Yonatan’s body was being stored. An older nurse looked at my paperwork and made a feeble attempt at empathy.

“How are you taking him?” she asked.

“Ambulance,” I said right away, and she nodded.

“Should I order one for you?”

“Yes, please.”

“Okay, you can wait over there,” she said, pointing her chin in the direction of a small waiting room. Then she picked up the phone and began to dial.

A small TV, resting on a metal arm that protruded from the wall, showed soundless footage from the government channel. Two stern-looking men spoke to one another. One, who looked like the guest, was religious, with a black yarmulke, a thick beard, a white shirt, and a black jacket. The man who looked like the host wore a knitted yarmulke and a blue dress shirt. His beard was trimmed and sculpted. Every once in a while a few passages from the Bible appeared on the screen and then disappeared. The two men were visibly excited, waving their fists, punctuating with their hands, making expansive gestures, smiling at the camera, twisting their faces into occasional grimaces, underscoring again and again their wonder at the potency of Biblical verse.

“Shalom,” the Arab ambulance driver said to me in halting Hebrew, perhaps on account of my clothes and perhaps on account of my physical appearance.

“Shalom,” I responded, rising to my feet.

“You’re accompanying the body, right?” he asked with no preamble and no superfluous attempts at commiseration.

“Right.”

“To Beit Safafa?”

“Yes, to the small mosque near the. .”

“Yeah,” the driver said, handing me a copy of some paperwork, “I know the place. I’m from there. You going to follow me?”

The driver lit a cigarette on the way to the ambulance, giving his younger assistant time to walk over to the stretcher and the enshrouded body and push it toward the ambulance. The driver opened the back doors and the younger man pushed a button on the stretcher and shoved it into the ambulance, the legs of the stretcher folding into the track.

They drove slowly, and I followed. For some reason I felt a burning desire to take photographs. It seemed to me like the only reasonable way to pass the next few minutes, behind the lens of a camera. To press, swivel, document, hide, distance myself from the events. But even if I had brought the camera with me, I doubt I would have had the nerve to use it. On Army Radio a famous Israeli singer spoke about his experiences during the past week, softening his voice, making it sound thoughtful, trying to enliven the banal conclusions that he had reached regarding his life.

“This next song has accompanied me during sad and happy days alike,” he said after he had finished his little speech and before he let the music speak for itself.

The ambulance entered the village and immediately drew the attention of the locals. Kids on bikes trailed behind the ambulance and pedaled furiously in their attempts to overtake the two-car convoy. The driver opened his window and told them something, probably that nothing exciting was happening, that this was just the body of a stranger being brought to burial, not someone from the village. A crowd tumbled out of the small mosque near the cemetery. The men stopped and stared at the ambulance and waited to see what was going on. I berated myself for forgetting that there was this little thing called Friday prayers and that it was the absolute worst time for a clandestine burial. I parked behind the ambulance and stayed inside the car. The driver turned around and threw me a look. Three men, one of whom seemed like the man in charge and the other two his helpers, came up to the ambulance driver and shook his hand, smiling. They exchanged a few words and looked over at me. A few of the worshippers came over and spoke with the men, whispering, and once they realized that it was not a villager who was being brought for burial and their curiosity had been satisfied, they left and went to report back to their friends that there was nothing to see.

I got out of the car only after all of the worshippers had dispersed. The driver’s assistant pulled Yonatan out of the ambulance and wheeled him toward a small room adjacent to the mosque, the two young men from the burial society trailing behind him.

“He can go to hell,” an elderly man said to me in Arabic as I stood there. “Who’s going to pray for this dog?”

“Shalom,” the man in charge of the burial service said to me in Hebrew. “Don’t worry about it, we’ll take care of this. You staying here?”

“Yes,” I said, not understanding exactly what was happening.

“He has no family members?”

“Not that I know of,” I said.

A little kid on a bike circled around us and yelled in Arabic, “How long are they going to bury collaborators here? How long?” The man in charge barked at him to get lost. “Sure,” the kid yelled. “What do you care? For you it’s good business. You couldn’t give a damn.”

“Get out of here, now,” the undertaker yelled, “or the first place I’m going to go after I’m done here is your father’s house. Get out of here.”

The kid pedaled off and the ambulance driver laughed and said the kid was right. “They’ve turned our cemetery into a garbage dump for foreigners,” he said in Arabic, and the undertaker looked at him apprehensively. “Don’t worry about it,” the driver said, looking at me. “He doesn’t understand a word, this one.” The stretcher was brought back to the ambulance and the driver and his assistant shook hands with the undertaker, bid him farewell, and drove off.

“You’re not a family member, right?” the undertaker asked me.

“No.”

“So, what is this, your job?”

“Yeah, among other things,” I found myself responding.

“You know how this works?”

“No.”

“The boys are washing him now. Then he goes into the mosque for a brief prayer and then we bury him. The grave has already been dug.” He pointed to a far-off corner of the cemetery. “Everything’s ready. You want some coffee?”

“No,” I said. “Thank you.”

The washing ceremony was brief. The two young men emerged with the body in a wooden coffin and hurried into the mosque.

“Just a second,” the undertaker said to me and jogged over to them. No prayer for the dead had been recited, of that I was sure. The coffin hadn’t been inside the mosque for more than a minute and the two men were coming out, carrying the coffin, walking briskly across the street that separated the mosque from the cemetery.

“Who died?” asked a driver who’d stopped his car.

“A foreigner,” the undertaker said. “ Allah yirachmo, a foreigner. A foreigner.”

The man drove off and the undertaker turned to me. “That’s it, they’re burying him,” he said. “If you’d like, you can leave a little something for the young men.”

“Yeah, let the little fucker pay,” one of the young men said as he walked with the coffin toward the grave. His partner laughed.

“Shut up,” the undertaker yelled at them, his face showing sorrow and disappointment.

“Of course,” I said, and I took two fifty-shekel notes out of my wallet.

“Thank you very much,” the undertaker said, parting from me quickly and walking toward the cemetery. I heard him say, “You’re making me look bad,” to the two men as they lowered the coffin into the ground. I got back in the car and started the engine. From afar I could see the heads of the two young men bending down to the ground and the undertaker directing them with his hands. I imagined that they had laid out the usual five blocks and that they were placing them on the body and then filling in the ditch with sand, spade by spade. I sat there and watched them work. One of the young men spat into the grave and laughed.

UNDERGROUND PARKING

The lawyer parked his car in the lot above King George Street. It was nearly nine in the morning. He turned off the engine and stayed in the car. The lawyer was scared. Where had all of this come from? He was afraid that this uncontrollable feeling would destroy his life and his career, make him lose his clientele and his livelihood. What was he worth without them? A month or two without any good cases and his life would start to unravel. The salaries, the mortgage, the car payments, taxes, shopping, his son’s nanny, his daughter’s school. The lawyer could see his life begin to crumble. Why had she done this to him? Didn’t she see that he’d been working like a mule to support them? He was always apprehensive that a young lawyer would come up and knock him off the top spot, but who would have thought that he’d be undone by matters of love and betrayal? Instead of showing up in court and representing an important client against charges of unlawful possession of a firearm, he was out and about on the streets, prowling around for his wife’s car like a jealous teenager.

There were five floors of underground parking at the Ministry of Social Affairs’ west Jerusalem office in Talpiot, and the lawyer drove slowly along the avenue of parked cars, eyeing each and every one.

Having not found his wife’s car, he made a U-turn and started back to the ground-floor exit. As he approached daylight, his phone announced two messages. The lawyer looked at the screen and saw that he had missed two calls while underground. One from Samah and one from his wife. He called his wife but once again she did not answer. The lawyer left Talpiot and drove toward the mental health clinic where his wife worked two or three days a week. What did she do there exactly? he wondered as his phone rang again.

“Is everything all right?” she asked. “I saw you called but I couldn’t answer because I’m in a meeting and my phone is on silent. I just stepped outside. Is everything okay?”

“Yeah,” the lawyer said. “What kind of meeting?”

“A staff meeting.”

“At the mental health clinic?”

“Yes. There’s a staff meeting every Sunday. We present cases. If everything’s okay then I’m going to go back in. You sure everything’s okay?”

“Yeah, everything’s fine. I’m just stuck in traffic.”

And still the lawyer drove to the clinic to look for her car. But even when he saw it, he felt that it was possible that his wife had deceived him and that she had parked there and then taken a taxi. He tightened his grip on the steering wheel and exhaled. He was sweating. He tried to loosen up, stretch his muscles. He was not thinking logically anymore, he seemed to be losing his mind.

There’s no reason for this, he told himself, there’s no reason to act like this. Your life is fine. Your life is in order. You are heading into an office that is humming with work; you will always have clients. Your caseload and your income have gone up each year. Clients don’t just melt away, nothing has changed.

“He’s dead,” Samah announced when the lawyer walked into the office.

“Who?”

“Your guy.”

“What? That’s not possible,” he said, putting down the little cardboard tray and the three cups of coffee. The phones rang.

“Lawyer’s office, please hold,” Samah said, laying the phone down on the counter. She pulled a piece of paper out of the fax, handed it to the lawyer, and got back on the phone. “Sorry for the wait, how may I help you? Hello, Abu Ramzi, how are you?” Samah looked at the lawyer and he shook his head, making clear that he could not take the call. “No, I’m sorry, he’s not in the office right now. He’s in court. Yes, of course, I’ll give him the message. ’Bye.”

The lawyer sat down on his office couch and looked at the fax from the population registry. Amir Lahab, born in Tira, 1979. The lawyer took out the note Samah had given him with the ID number she had received from the outpatient clinic in east Jerusalem and made sure that the numbers matched. According to the population registry, this Amir Lahab had died on Thursday, a little over a week ago. What kind of coincidence was that? Now, while he was searching for him, the guy just happens to die?

Impossible, the lawyer thought, something is wrong. There’s no way he’s dead. Just yesterday he had spoken with the man’s mother, who did not seem to suffer from mental illness, and she had said she had spoken to him over the course of the past week. The lawyer leaned back on the couch and ran his hands back and forth through his hair.

“What’s wrong?” Samah asked, coming into the room with the lawyer’s cup of coffee.

“Nothing,” the lawyer said. “Nothing.”

“Did you know the deceased?”

“What?” It took him a moment to understand her question. “Oh, no, no. Listen,” he said, sitting up straight and pulling two books out of his briefcase, One Hundred Years of Solitudeand the one featuring the work of Egon Schiele. He flipped through the first pages of the novel and showed Samah the signature, Yonatan. “Scan this page, please,” the lawyer said, “and this one,” he said, showing her the signature on the art book, “and send them to the graphologist. Tell him it’s very urgent. And that there’s no need for an official report.”

Samah took the two books. “What should I ask him?”

“What? Oh, ask him to compare the two signatures. Circle the name Yonatanon both of the documents.”

Once she’d left the room the lawyer looked around for the telephone number that he’d gotten from Meissar, the mother from Jaljulia. What would he say to her? Did you know that the son you spoke with last week is dead?The lawyer wanted to check the ID number, ask if there was anyone else from Jaljulia with the same name, but he knew those kinds of questions would make her suspicious and would not likely be answered.

“Hello?”

He heard her voice and hung up the phone.

GARBAGE CANS

On Thursday, after the shiva, Ruchaleh packed a big suitcase full of clothes and moved into a hotel room until she could find herself an apartment. Selling the house was a chore she left for me to take care of. “Leave whatever you leave, take whatever you take,” she said when I dropped her off in front of the hotel.

She had probably been waiting for this moment just as I had, played the day-after scenario in her head thousands of times. She knew exactly what had to be done, knew which suitcase to take, which clothes to pack. She had not shown any sign of hesitation when she walked out of the bedroom with her suitcase and took five books off the shelf in the living room – books she may have chosen years ago – and then walked into her study and back out again with a bag slung over her shoulder.

I think I may have thought about this moment more than Ruchaleh, and I was sure that when the time came, after months of nightly planning, I would get things done on autopilot, briskly moving from chore to chore. But on the way back from the hotel I felt myself start to lose my train of thought and everything that had seemed so clear started to blur.

When I got home I called the real estate agency that Ruchaleh had decided to work with. Upon hearing that there was a private house in Beit Hakerem going on the market, they insisted on sending someone that same day. I had to be very firm with the real estate agent and tell him that the earliest I could see him was Sunday, though I reassured him that I would not speak with other agencies in the meantime.

Ruchaleh had said I could stay at the house as long as there was no buyer but I knew I would never be able to sleep there alone, not even for one night, without her and without Yonatan. Sterilization—that was my code word for the initial first step. No trace, I said to myself as I started emptying the attic drawers and dumping the contents into garbage bags.

I tried not to look at the contents of the desk drawers, which I knew so well, but rather to pull each one out, dump everything into a bag, and move on without pause. There was no time for contemplation. Diaries, pictures, report cards, drawings from kindergarten, letters. I still wasn’t sure if these things should be shredded or burned.

Having finished the desk I moved on to the closet. I pulled the two gym bags my mother had bought me off the top shelf and stuffed my old clothes inside. After five years of neglect the clothes looked pathetic. They’re not mine, I tried convincing myself, and I shivered. They’re not mine. I brought the blue sweater to my face and sniffed it; that is not my scent, I said to myself, and I used the sweater to wipe away the tears, scratching them off my face, and then I shoved it into the bag.

The plan was to lay the old clothes outside next to the garbage cans, as all of the neighbors did, donations to the Arab garbagemen. These bags, though, I thought, might look suspicious to the neighbors. They usually left their belongings in see-through bags and not in old canvas gym bags that could look suspicious. I unzipped the bags, dumped their contents into the garbage, and then folded the bags and tossed them in, too.

I packed my new wardrobe in a suitcase that I had bought earlier in the week and, since I had promised Ruchaleh that I would leave the attic empty, I took all the things I didn’t want, threw them into garbage bags, and put them out on the curb. The eggshell mattress, the wheelchair, the ventilator, and all the rest of the medical supplies were to be picked up the following day by the Yad Sarah organization. They were delighted to hear that I was interested in donating all of the furniture in the room, too.

Noa was in class when I arrived at her house but she had left me a key, just as she’d promised, right under the mat. Despite Noa’s love of music, all she had was a little compact stereo with poor sound so I brought her Yonatan’s stereo and his electric guitar, presents for allowing me to stay with her until I found a place of my own.

After dropping everything off at Noa’s, I went back to the house to pack up the CDs and the books. The bag with the stuff from Yonatan’s drawers, I decided, should be thrown out somewhere else, far away.

TWO-HUNDRED SHEKEL NOTES

“I’ll be back in five minutes,” the lawyer told Samah, who was holding the phone in one hand and sending the graphologist a fax with the other. On the way down the stairs he bumped into Tarik.

“So?” the lawyer asked.

“Good news! In the end the prosecution were the ones who were reprimanded.”

“You didn’t have to ask for a continuance?”

“No, the police never even managed to bring in the accused.”

“Great,” the lawyer said, smiling a genuine smile. “All right, I’m headed out for five minutes. Your coffee’s waiting for you, probably already cold.”

The lawyer was happy he hadn’t had to ask the court to reschedule the hearing. He took it as a sign. Maybe everyone was not against him and maybe the luck he had always had had not run out. Just one tiny little inquiry and then it’s over, the lawyer promised himself. One more thing and then I’m putting this entire thing behind me. I don’t care if this Amir is alive or dead; if his mother spoke to him or not. Enough. After I look into one more thing I will go back to believing in my wife’s version of events.

“Oh, good morning,” the lawyer said to Meirav when he saw her behind the counter of the used bookstore reading the paper.

“Good morning,” she said. “What’s up? What are you doing here on a Sunday, in the morning no less?”

The lawyer laughed and hoped he sounded credible. “You’re right,” he said, looking around for Yonatan’s boxes, “something is up.”

“What?” Meirav asked.

“On Thursday I came in and bought The Kreutzer Sonata,you remember?” He showed her the book.

“Yeah, I remember. What about it?”

“It’s a great book. I just wanted to ask if you knew who sold it to you?”

“Sure,” she answered. “I was the one who was working when all the stuff came in on Thursday. Why?”

“Do you think you could give me, I don’t know, the person’s number or e-mail or something?”

“No, sorry. We’re not allowed to give out the numbers of sellers or buyers. If it’s something important and you really need his info, you better talk to the owner.”

“I understand,” the lawyer said. “It’s kind of like attorney-client privilege or something, right?”

“The owner’s pretty strict about it,” Meirav said. “He’s worried people are going to steal his clients or, even worse, his sellers.”

“Okay, fine,” the lawyer said, opening the book. “The thing is, Meirav, that while I was reading I found these between the pages of the book.” He produced a pair of two-hundred shekel notes.

“Oh,” Meirav said, looking confused.

“I think these might be Yonatan’s,” the lawyer said, watching her face for a reaction.

“Yeah, they must be.” She typed something into the computer. “I’ll call him and tell him to come pick it up.”

“Hi, is this Yonatan?” Meirav said into the phone. “Hi, I hope I’m not disturbing you. My name’s Meirav and I’m calling from the used bookstore. We met on Thursday when you brought the books in, remember? No, no, everything’s fine, it’s just that someone found two two-hundred shekel bills in one of the books. Yeah. So I was thinking, I don’t know, maybe we could send it over to you or you could come by and get it.” Meirav was silent, she nodded her head and looked at the lawyer. Then she said, “I don’t see why not, it’s your money.”

The lawyer gestured to Meirav that he would like the phone. She said, “Just a second, the customer who found the money wants to talk to you. Just a second,” and she handed him the phone.

The lawyer took a deep breath.

“Hello, Yonatan?” he said, his voice rising at the end to form a question.

“Hello,” said the voice on the other end of the line. The lawyer could hear noise all around him.

“I bought The Kreutzer Sonataa little while ago and. .” the lawyer’s voice wavered.

“I know, it’s okay,” the other man said. “It’s fine. I don’t want the money. Do whatever you want with it. Give it away, take it, give it to the store, I don’t care.”

“I understand,” the lawyer said, wondering what to say next. It sounded to him like the voice on the other end of the line had left the noise and was searching out a quieter place. “The thing is, aside from the money, I also found the note.”

“What note?”

“A note in Arabic, and that’s why I’m here.”

“Sir,” the other man said impatiently, “I don’t know what you’re talking about, and I’m heading into a class so I’m going to hang up now.”

“Do you know Arabic, Yonatan?” the lawyer asked, looking over at Meirav, who was starting to fidget, apparently regretting ever handing the phone to the lawyer.

“Why do you ask, sir? Who are you?”

The man’s response told the lawyer that he was on the right track.

“Yonatan,” he said, this time more forcefully. “Do you know someone by the name of Amir Lahab?”

“Who are you?” The lawyer could hear the fear in the man’s voice. “Can you please tell me who you are?” the man said, practically begging.

The lawyer decided to end this part of his investigation. “So, should I bring you the money when we meet up?” he asked.

“Why should we meet up? I just told you that I don’t want the money. What do you want from me?”

“No problem,” the lawyer said, smiling at Meirav. “No problem. I’ll bring the note, too. Okay, have a good rest of the day. They have your address? Great, excellent. Okay, see you soon.” The lawyer hung up the phone without waiting for a response. He looked at Meirav and grinned. “What kind of person says no to cash?”

“He wanted it?”

“Of course,” the lawyer said. “He sounded really busy, though. He asked that I take it over to his house. Sounded like a nice guy. And he definitely has good taste in books.”

“No doubt,” Meirav said. “There were some amazing books in there.”

“Okay,” the lawyer said. “I’ll head over there. Could you tell me how to go? What’s the shortest way to get there?”

“To 35 Scout Street?” she asked, looking at the computer screen. “The best thing to do is take Bezalel Street all the way to Herzl and then make a left.”

“Great, thanks a million.”

ASIGN AND A BELL

The lawyer was feeling pleased. He’d taken care of everything he’d set out to do. His wife was at home with the kids. How could he have thought, only earlier that morning, that she had beaten him to the punch and filed first for divorce? The matter of her car and the five floors of the parking garage also brought a smile to his lips. True, he hadn’t yet found an intern. Only two out of three had shown up and neither had made a particularly good impression, especially not on Tarik.

“Both goody two-shoes,” Tarik had said after the interviews. “So what, so they have good grades? They’re both spoiled little girls who’ve never seen anything outside a textbook and don’t know a thing about how the world works.”

“So we’ll wait for next week, there’ll be more candidates,” the lawyer said, laughing. “And yes, they really weren’t very kind on the eyes.”

He was also pleased that he was close to finding the answer to the riddle. And now, on his way to Beit Hakerem, that was all that remained of the whole sordid affair: the riddle, the challenge. He had seemingly forgotten about his wife’s involvement in the matter and now only sought to find out who Yonatan was, who Amir was, what the two had to do with each other, and how the whole thing had happened.

It’s possible that the lawyer was tickled by the notion that Amir and Yonatan were actually a couple. If that turned out to be the case, he’d be delighted. If it turned out that his wife, before he had come along, had been in love with a gay man, it would make him the happiest person in the world. In his mind the old picture of the tough, tall, muscular Arab with the giant cock turned into one of a dainty little porcelain-faced faggot dancing with his wife at the party. It was true that in public the lawyer had never said anything against homosexuality and, in fact, took pains to publicly say that every person is free to choose whomever he or she wants to spend their lives with. He also railed against the persecution of homosexuals in Arab lands and in Iran and said that this type of treatment was a sure sign of social and cultural malaise, a fundamental lack of openness among the Arab and Islamic communities. And yet the notion of his wife dancing around with a gay man filled him with an undeniable giddiness.

The lawyer slowed down and looked at the numbers on the houses. He parked his car outside of 34 and looked across the street for 35. A small gate led to a garden and a large house. There’s no way a social worker could afford this place, the lawyer thought as he waited outside the front door, thinking that the house looked a lot more like a family home than the pad of two young gay men. The neighborhood was quiet. No cars came down the narrow street and, other than the barking of dogs and the whirr of cars on the nearby avenue, the lawyer did not hear a thing. On the front door there was a wooden sign with the name Forschmidt.

The lawyer knocked softly with his fist on the wooden door. In his hand he held The Kreutzer Sonata,his wife’s letter, and the two two-hundred-shekel bills. No matter who opened the door, the lawyer had decided to be straightforward. To tell the truth and to ask for answers. I bought a book that Yonatan sold, he rehearsed, and in the book I found a letter in my wife’s hand. I was wondering why that was. Just curious. What’s more, she said she had written that note to a colleague by the name of Amir Lahab. The lawyer knocked again but there was no response. He hit the bell, listened to its muffled ring inside the house, and waited for some time until the door opened.

MEETING

“Shalom,” I said to the man at the door, sure he was the real estate agent. “Please, come on in, you’re a little bit early but that’s fine.”

“I think you might have me confused with someone else,” the man said, still standing at the door.

“You’re not the real estate agent?” I asked.

“No,” he said and a huge smile spread across his face. Now I started to notice the Arabness of his look and his accent, and I knew without a shadow of a doubt that this was the voice from the bookstore earlier in the day. “You’re Yonatan,” he said, with only the trace of a question.

“Excuse me,” I said, “but who’s asking?”

“No one,” he answered, still smiling. “Just a lawyer who’s looking for Yonatan.”

“Why, what did he do?”

“Nothing,” the man said. “He didn’t do a thing. I believe, though, that I bought a book that he sold.” He raised The Kreutzer Sonataup to eye level as though it were an important piece of evidence. “I found a few hundred shekels inside and I said that I simply had to return them to him.”

“Thank you,” I said. “If you’d like I can give them to him.”

“So, then you’re not Yonatan?” he asked.

“I don’t see why it matters, sir,” I said.

“It doesn’t matter,” the lawyer said, pulling a folded white piece of paper from the book. “But I found a note in the book, too, and it seems to be a bit more personal than money, so I thought I would hand it over to Yonatan in person.”

“I’m Yonatan,” I said impatiently. By now I was sure that the unexpected guest was an Arab.

“Please forgive my audacity,” he said, as though performing before a packed courthouse, “but could you please show me some ID?”

“Sir, I have no idea who you are. You come to my house with an old book and some story about money. I don’t care about the money and I don’t care about the note. I don’t want to show you my ID and I don’t want to continue this conversation.” I held the door open and only a lifetime of good manners stopped me from slamming it in his face. I waited for him to leave, but perhaps I already knew that this was the first stage of what was going to be a long conversation.

“Your name’s Amir,” he said sharply in Arabic.

“What?” I said, trying to stick to Hebrew. “Who the hell are you? What do you want from me?”

“I know who you are,” he went on in Arabic. “I visited with your mother in Jaljulia yesterday. I wonder what she’ll think when she discovers that her only son is dead.”