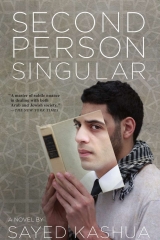

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Sayed Kashua

Second Person Singular

To my parents

PART ONE. THE BRATZ BEDDING

The moment the lawyer opened his eyes he knew he’d be tired for the rest of the day. He wasn’t sure whether he’d heard it on the radio or read it in the newspaper, but he’d come across a specialist who described sleep in terms of cycles. Often the reason people are tired, the specialist explained, was not due to insufficient sleep but rather a sudden awakening before the cycle had run its course. The lawyer did not know anything about these cycles – their duration, their starting point, their ending point – but he did know that this morning, in essence almost every morning, he rose right in the middle of one. Had he ever experienced what must be the wonderful sensation of waking up naturally, at the tail end of a cycle? He wasn’t sure. He imagined sleep cycles like the waves of the sea and himself as a surfer upon them, gliding toward shore and then suddenly, violently, being tossed into the water, waking up with a terror he did not fully understand.

The lawyer was internally programmed to wake up early, and yet, when he had to be in court in the morning, he would set the alarm on his cell phone, even though he knew he would jolt awake before it rang.

The sounds of his family’s morning routine floated down to his bed. Or rather, his daughter’s bed. She was six years old, in first grade, and ever since her birth the lawyer had made a habit of sleeping in her room. As a baby, she woke up often in the middle of the night, in need of nursing, changing, and soothing, and it was at this time that the lawyer first altered the family’s sleeping arrangements. The baby slept in a crib in her parents’ bedroom, alongside her mother, who tended to her, and he slept alone on the floor of his daughter’s room, on a mattress.

At the time, his wife did not begrudge him this arrangement. She knew her husband needed a full night’s sleep in order to function properly at work, and she, enjoying a full year of maternity leave, was not saddled with the difficult and demanding work of a young attorney who was just beginning to establish himself as one of Jerusalem’s most promising criminal lawyers.

So for two years, the lawyer slept on a thin mattress laid over a Winnie-the-Pooh rug, the bear sailing along in the basket of a hot air balloon, surrounded by four serene, sky-blue, cloud-graced walls and a posse of stuffed animals, some of which were gifts from family and friends, and others, the bulk of the collection, bought by the couple for their firstborn child, who continued to sleep in her parents’ bedroom alongside her mother. Ever since their daughter had begun to sleep through the night, the lawyer had been visiting his wife several times a week, staying in their bed until morning. Occasionally, his wife would pay him a visit, but he preferred the former arrangement, because the toys, housed on the shelves and in the drawers – teddy bears, puppies, and innocent dolls in wedding dresses – seemed to peer out at them in fear and astonishment, aghast at the strange ceremony being performed right beneath their noses.

When their daughter turned two, the couple decided it was time for her to make the leap from crib to toddler bed. She was tall for her age – and still is, even today, looming a full head over the rest of her classmates – but even after buying the new bed, a pink race car that contrasted nicely with the sky-blue walls and the floating clouds, the lawyer continued to sleep in the girl’s room and she began to sleep on his side of the queen bed with her mother. The lawyer’s life, though, took a turn for the better with this new stage in his daughter’s development because the toddler bed came equipped with an orthopedic mattress.

Last year, the couple had a second child, a son. Several weeks after his birth, the couple moved out of their rented apartment and into a duplex that they had built and designed to their specifications. The upper floor consisted of a large living room, a designer kitchen, and two bedrooms, one of which was especially large – the couple enjoyed calling it the master bedroom, a term they’d only recently acquired – and another that had been outfitted for the new baby boy, with sky-blue ceilings and Shrek wallpaper. The girl’s room was downstairs. It was airy and cream-colored, with a matching bed, desk, shelves, and a spacious purple-and-cream closet. The bottom floor also had a bathroom, a small storage room, and an office, the lawyer’s sanctuary – an antique mahogany desk, a gift from one of his clients, dominated the book-lined room.

The move to the new house did not alter the couple’s sleeping habits. Their son was still an infant and his mother preferred that his crib be near her bed, and their daughter, despite all attempts to convince her otherwise, was scared to sleep alone in her room. The lawyer and his wife, sensitive to her fear of being alone on the bottom floor, suggested that she sleep on a mattress in her brother’s room. She agreed, but nearly every night she woke up terrified and ran straight to her parents’ room. And that is how the lawyer found himself back in his daughter’s bed. Not that he minded. At the end of the day, the lawyer preferred sleeping alone.

The lawyer heard his wife’s shrill voice ordering their daughter to wash her face and brush her teeth. Her quick and cantankerous steps reverberated through the ceiling. Why does she walk like that? he wondered. It was like she was making a point with her feet. Boom, boom, boom. Red Army soldiers on parade. “How should I know where your hair scrunchies are?” he heard his wife yell. “Maybe next time you should be a little more careful with your things. You’re not a baby anymore, you know. Let’s go. Quick. Downstairs, get dressed, and make sure you have all your school books. Too bad. No hair scrunchies. You’ll make do. Let’s go. I don’t want to hear another word. I’m late.”

The lawyer recognized his daughter’s chastened steps on the wooden stairs and the sounds of his wife, blowing her nose in the bathroom and spitting as she brushed her teeth. He thought about his wife, about the noises she made, and wondered if there was a way to tell her how awful it sounded. He was sure that, if she knew, she would change her ways. The toilet seat came down with a thud and his daughter pushed open the door to her room. Her eyes, as he expected, seemed to be seeking shelter from her mother’s scolding.

The lawyer smiled at his daughter, peeled off the Bratz blanket, sat up in bed, and motioned to her to come sit beside him – the exact sign she had been waiting for. She wanted to know whose side he had chosen this morning, and the smile and the invitation for a hug reassured her. Who knew, perhaps he’d even criticize his wife, admonish her. “I didn’t lose my hair thingies,” the girl protested, sitting in her father’s lap. “I put them next to the sink yesterday before I went to bed. Why’s she yelling at me? Tell her, Daddy, I didn’t lose them.”

“I’m sure we’ll find them soon,” the lawyer said, caressing his daughter’s hair.

“We’ll never find them. And anyway, they’re old. I need new ones, lots of new ones, so that if some of them get lost there’ll still be more. Okay?”

“Okay,” the lawyer said. “Now get dressed. We don’t want to be late, all right, sweetheart?”

“I don’t have anything to wear,” she said, pouting as she peered into her closet. The lawyer smiled at his daughter again and left the room. He considered going into the master bedroom to wish his wife a good morning and then wondered whether she’d come downstairs to greet him, but he did not go in and she did not come down. The lawyer had no tolerance for false gestures. He had heard often, from clients and experts on TV, that the way to ensure quiet on the home front was for the husband to deceive the wife, to compliment and praise her at all times, but that quiet, of the kind they were referring to, he already had aplenty. The lawyer could not contend that his wife henpecked him; on the contrary, she ran the house and took care of the kids with unwavering authority and never complained when he stayed late at the office or refrained from helping around the house. As he went upstairs and into the kitchen to make coffee, he considered these things, satisfied that his wife harbored no complaints.

He heard her cooing to the baby as she dressed him. He could have popped into the bedroom and she could have stopped by the kitchen. Instead he made his way back downstairs with a cup of coffee. He saw that his daughter was getting dressed in her room and then continued on to the study, shutting the door behind him. This was the only smoking room, in accordance with his house rule. This applied to everyone. If any of their guests wanted to smoke, they were welcome to step out onto the patio or to go downstairs. The lawyer’s wife did not smoke.

SCHOOL

After checking that his daughter was properly buckled into the backseat of his black Mercedes-Benz, the lawyer looked over at his wife and saw her strapping the baby into her blue Volkswagen Golf. Ordinarily, his wife did the dropping off – their daughter at school and the baby at the nanny’s house, a two-minute drive away – but on Thursdays, the last day of the work week for most Israelis, she worried about being late to her staff meetings, which started at eight o’clock sharp. The lawyer was rarely in a rush to get to the office on Thursdays so on this day alone they divided the labor.

The lawyer’s wife clicked open the garage door. She came up to the lawyer’s car and waved to her daughter. “Bye,” she said to her husband, got into her car, and was the first to leave. She turned around and looked back at her husband and waved once again, smiling with gratitude. The lawyer nodded his head and sat down in his car. He felt himself a supportive husband who encouraged his wife’s endeavors. True, other than dropping their daughter off on Thursdays he did not do much around the house or on the child-care front, but even small gestures, like taking their daughter to school or on occasion coming home early from work so that she could attend a conference or some work-related social function, were seen, by both of them, as major career sacrifices. They were aware that there was no comparing their salaries, the lawyer’s and the social worker’s, and though the lawyer never mentioned this to his wife, his friend, who was also his accountant, had told him that if his wife were to quit her job and stay at home, their income would actually rise. As a sole income earner, their tax breaks would amount to more than his wife’s annual salary.

Mulling these things over as he drove his daughter to school, the lawyer realized that he did not know exactly what his wife did at work. That is to say, he knew she had a bachelor’s degree in social work and that when they first met she had been working at the welfare office in Wadi Joz, in east Jerusalem, and that she had been enrolled in a master’s program of some sort. He also knew that she had, over the years, attained an additional master’s degree, in something therapy-related. He felt he had always encouraged her to study, always supported her, but he could not say with any degree of certainty what she did at her current welfare job in the south of the city, where she worked part-time, nor did he know whom she treated at the mental health clinic, where she held an additional part-time position. All of a sudden, before flipping on the radio to hear the seven-thirty news flash, the lawyer wanted to know what, for instance, those Thursday morning staff meetings looked like, the ones she was always nervous about being late for.

He drove slowly through the neighborhood’s narrow streets, sunglasses shielding his eyes. Sometimes there was traffic at the main intersection, where hundreds of day laborers waited to be picked up. The young, strong-looking ones were selected early in the day, and by seven thirty in the morning all that remained were the older, weaker men. Contractors who woke up late would have to make do with them. At close to eight in the morning, when the lawyer generally crossed through the intersection, there was only a smattering of lonely workers. The sight always stung. What did the locals think of him? What did they make of Arabs like him, citizens of the state? With their luxury cars and their ostentatious lifestyles, the ones like him, who came here for college and stayed for financial reasons, immigrants in their own land. The Israeli Arabs with independent careers are the ones who avoid beating a track back to the villages of the Galilee and the Triangle. They are frequently lawyers, like him, or accountants or doctors. Some are academics. They are the only ones who can afford to stay and live in a city where the cost of living, even in the Arab neighborhoods, is many times higher than in any village in the Galilee or the Triangle.

Lawyers, accountants, tax advisors, and doctors—brokers between the noncitizen Arabs and the Israeli authorities, a few thousand people, living within Jerusalem but divorced from the locals among whom they reside. They will always be seen as strangers, somewhat suspicious, but wholly indispensable. Without them who would represent the residents of east Jerusalem and the surrounding villages in the Hebrew-speaking courts and tax authorities, against the insurance companies and the hospitals? Not that there is any great lack of doctors, lawyers, or economists among the east Jerusalem Arabs, but what can be done if, more often than not, the Israeli authorities do not accept their credentials? A higher education from somewhere in the West Bank or from another part of the Arab world does not suffice in Israel; a whole slew of supplementary material and a battery of tests, the vast majority of which are in Hebrew, are required. A few of the east Jerusalemites actually push through the grueling Israeli accreditation process, but the lawyer also knew that many of the locals preferred to be represented by someone who was a citizen of the state of Israel. He, so the lawyer felt they thought, was surely more familiar with the workings of the Jewish mind and soul. He, they believed, could not have attained his position in life without connections, kosher or otherwise. Somehow, in the eyes of the locals, the Arab citizens of Israel were considered to be half-Jewish.

The lawyer pulled his luxury sedan into the parking lot of the Jewish-Arab school, which had been founded by Arabs like him. They did not want their children educated in the east Jerusalemites’ schools, public institutions infamous for their physical and pedagogical decay. The Israeli-Arab immigrants in Jerusalem wanted their children to study as they had, in other words in a school under the auspices of the Israeli Ministry of Education, a place that issued matriculation certificates that were recognized in Israel and internationally, as opposed to the east Jerusalem system, where, until recently, they had followed the Jordanian system, and, more recently, since the founding of the Palestinian Authority, the dictates of the Palestinian Ministry of Education. But even they, citizens of the state, educated people in positions of power, knew that they had no chance of setting up a school for their children without coming up with a novel idea. An immigrant from the Galilee, a PhD in education, found the solution: mixed bilingual education. He founded an NGO, called it Jews and Arabs Study Together in Jerusalem, and easily raised the money from European and American philanthropists seeking to promote peace in the Middle East.

The mostly Arab school board, with the assistance of the parent-teacher association, did all they could to ensure that only the children of the Arab citizens of Israel – these immigrants-in-their-own-land – would study in the school alongside the Jewish students, but they were unable to completely bar the acceptance of local Arabs. The board voiced their objections in nationalist terms, stating that the joint Arab-Jewish educational venture was meant for the Arab citizens of the state and not the Jerusalemites, who were part of the occupied West Bank. They argued that inclusion of the local children would violate their political beliefs, according to which, Israel must withdraw from the West Bank and Gaza, and east Jerusalem must be liberated from Israeli occupation and crowned as the capital of Palestine.

But these convictions could not be brought before the municipality of Jerusalem and certainly not before the Israeli Department of Education, which insisted on seeing Jerusalem as the united and eternal capital of the Jewish people. Voicing these types of concerns before the Israeli authorities would put the school in danger of being closed down and the parents charged with heresy and political treason. Therefore, and due to the fact that the immigrants’ children were too few in number to fill the class quotas for Arabic speakers – the school mandate called for thirty students per class, half Arabs and half Jews – they were forced by the department of education and the municipality to accept several local kids.

It’s so easy to differentiate between the Jewish and the Arab cars, the lawyer thought as he walked from the parking lot to the entrance of the school, holding his daughter’s hand. The Jews’ cars were modest, affordable, generally products of Japan or Korea. The Arabs’ cars were expensive and German, with massive engines under the gleaming hoods and dashboards full of accessories; many of them were luxury SUVs. Not that the parents of the Jewish kids earned less – the lawyer could swear to the contrary – but as opposed to the Arab parents, the Jewish parents were not in competition, none of them felt they had to prove their success to their peers, and certainly not by upgrading their cars annually. Judging by the parents of the kids in his daughter’s class, the lawyer surmised that the Jews worked in a variety of fields. There were high-tech employees, several senior public servants from the foreign, finance, and justice ministries, a few professors, and two artists. A wide range of professions when compared with the Arab children, who had at least one parent, usually the husband, in law, accounting, or medicine. Most of the Arab mothers were teachers, generally senior staff – they were far more likely to rise up through the ranks of Jerusalem’s educational system than the local Arabs – but still, just teachers.

The lawyer, for his part, would have been happy to forgo the Mercedes and make do with a cheaper car. He had considered a top-of-the-line Mazda, but he knew he could not afford that. Even during the tough days after the purchase of the duplex, he knew that if he did not upgrade his car to a model that surpassed what the competition was driving, it would be seen as a retreat. He had to do everything in his power to ensure that he would remain, in the eyes of the public, the number one Arab criminal defense lawyer in the city, and a fancy black Mercedes was an integral part of that campaign. If one of his competitors bought a BMW with a V6 and three hundred horsepower, then he had to get the Benz with the V8 and a few hundred more horses under the hood. If the competition had optical sensors all around the car, he had to have DVD players built into the headrests. Not that the lawyer was having trouble paying back the loan he had taken to finance the car, but he certainly would have felt a little less pressure and would have had the luxury of being a bit more selective in the cases he took on if he had made do without the Mercedes. But he could not.

KING GEORGE

Five years ago the lawyer had moved his offices from Salah al-Din Street, the major thoroughfare in east Jerusalem, to King George Street, the main drag in the western half of the city. Aside from a few Jews, his clientele was based in east Jerusalem and the West Bank, and so on the face of things it made more sense for him to stay where he was, but the lawyer suspected that the east Jerusalemites, despite everything, had more esteem for a lawyer whose offices were located in a Jewish neighborhood. Forgoing his colleagues’ advice, he went with his gut feeling, and found, in a matter of months, that the move to King George Street, which entailed a tripling of the rent, was financially sound. In a year he had doubled his clientele and his income.

Not long after his move to the western part of the city, the lawyer realized that in addition to a permanent secretary and a rotating student intern, he also needed another lawyer to help with the caseload. One year after the move to King George Street, he offered the position to a former intern, Tarik, whom he liked and who reminded him of himself back in the day. He knew he could trust him and soon enough he managed to convince Tarik to abandon his plans of returning to the Galilee, where he had intended to open an office of his own.

“Why go back? Just so your dad can see the shingle on the door?” the lawyer had said to Tarik. “You want to spend your life working for the village car thieves, or deal with the real thing down here?” In order to show to Tarik what the real thing was, he sent the twenty-three-year-old lawyer, fresh from the bar exam, which he had aced, to file an appeal at the High Court of Justice in Jerusalem. Upon return, Tarik, feeling victorious, with an interim injunction in hand, agreed to the terms the lawyer had laid out, a monthly salary plus 10 percent of all income from the cases he handled.

The office secretary, Samah Mansour, had worked for the lawyer for eight years, ever since the lawyer had opened his private practice in the eastern part of the city. At first he had hired her part-time, but after a year he was able to offer her a full-time position. Samah, who was thirty years old, had graduated from law school in Amman and was looking for a law office where she could learn the language and the system, in hopes that she could one day gain entry to the Israel Bar Association. She had come to the interview accompanied by her fiancé. The lawyer knew that the woman seated before him was the daughter of one of the senior Fatah officials in Jerusalem, and he decided to give her a job even though she didn’t speak a word of Hebrew. He never would have admitted it but her father was the main reason he had hired her, especially since in those days he could hardly afford to pay her salary. But as a young criminal lawyer, he needed the seal of approval of a man like Mr. Mansour, Samah’s father.

Samah’s father ran for office in the first Palestinian parliamentary elections, was elected, and became, before long, a confidant of those in the upper echelons of the Palestinian government. Samah married her fiancé, a Kuwait-educated city planner, who had been working as a successful contractor ever since his return to Jerusalem. The couple had three children. By now she had a firm command of Hebrew, ran the office with a high hand, and seemed to have made her peace with her position, perhaps even deriving some satisfaction from it. Nonetheless, she took the bar exam every year and though she failed it close to a dozen times, she still insisted on trying her luck each year.

The lawyer pulled his car into the lot near his office and greeted the old guard with a hearty good morning. As usual, the man was busy brewing strong mint tea. The lawyer parked in one of the five spots he had rented – one for himself, one each for Samah and Tarik, whose cars were already in place, and two for important clients.

The old guard, black kippahon his head, waddled over toward the lawyer’s car, tea in hand. “Will you do me the honor of having a glass of tea with me?” he asked. The lawyer got out of his car and smiled. “Thank you very much, Mr. Yehezkel, but today I’m in a hurry,” he said, handing the guard the keys, as he did every Thursday, so that he could clean the vehicle. “You’re always in a hurry,” the guard said, adding in thick Kurdish-accented Arabic, “haste is from the devil.” The guard laughed a hearty laugh that ended in a cough.

“Good morning, Samah,” the lawyer said into his cell phone as he walked up King George Street. “They aren’t here yet, are they?” He knew that the clients scheduled to arrive this morning were not known for their punctuality and, furthermore, he had seen that the parking spots reserved for his clients were both still open. “Okay, so I’ll be downstairs in the café. Let me know when they come. Thanks.” He hung up the phone, tucked it into his jacket pocket, straightened his tie, and turned away from his office.

The lawyer liked starting his day with a double cappuccino at Oved’s Café but all too often he had to take it to go. Usually he’d find himself sipping his coffee out of a paper cup in his office. On especially busy days, he would very cordially ask Samah to do him a favor and get him some coffee from Oved, adding, of course, that she should get one for herself and whoever else was in the office. But Thursdays were different. They were quiet, practically dead compared to the rest of the week. The lawyer always made sure not to schedule court appearances on Thursdays. If something unforeseen arose, he sent Tarik. The majority of the day was devoted to paperwork.

“Good morning, Mr. Attorney,” Oved said as he brought a brass canister of milk to a steaming spout. “Good morning,” the lawyer responded, looking around the café, making sure he recognized all the faces. He didn’t know them all by name, and he certainly didn’t know them by profession, but Oved’s customers were loyal, and he nodded in their direction. Once he’d gotten some form of recognition in return, he sat down on one of the three bar stools. “For here?” Oved asked from behind the bar. “Yeah, you believe that?” the lawyer responded, nodding, stretching the skin on his forehead and raising his eyebrows.

Oved knew how his regulars took their coffee – how much milk, how many shots of espresso, how much foam, if any, and how much sugar. “You want something with that?” he asked as he began making the lawyer’s coffee. “Yes, thank you,” the lawyer answered, even though he didn’t want anything but coffee at this hour of the morning. Decorum, and the fact that he was occupying a seat in the café, compelled him to show some generosity and so he tacked a pastry onto the bill. “A croissant, please,” he said, nodding.

The lawyer liked Oved and felt that Oved responded in kind. He was the owner of one of the only independent cafés downtown and had also been one of the first people to welcome the lawyer to his new surroundings five years earlier. He was outwardly kind and jovial toward him and somehow the lawyer felt that it was on account of, and not despite, his being an Arab. At first the lawyer thought that Oved was another one of those Kurdish Jews, a Sephardic store owner whose tongue and heart were not in the same place, but soon enough he found that Oved’s political analyses were in line with his own. Occasionally, he even picked up on traces of bigotry that the lawyer had missed. Oved was the last of the socialists in the center of town or, as one of his regulars, an arts editor at a local paper, referred to him, “the one and only communist Kurd in Jerusalem.”

Morning was the café’s busiest time. Most of the customers, like the lawyer, worked in the area, and they took their plastic-lidded coffees with them to the clothing stores, shoe stores, hairdressers, travel agencies, insurance agencies, real estate agencies, law offices, and doctors’ offices. Oved was too busy for conversation with the lawyer, who sipped slowly and looked around often. The skinny journalist was there with a cigarette in her hand and a small computer screen flickering in front of her face. The art history professor, known to the lawyer mostly from his appearances on TV, sat before an open book. The real estate agent sat with a client, speaking loudly about soccer, and an elderly couple shared breakfast without exchanging a word. I wonder what I look like, the lawyer thought to himself as he examined his skewed reflection on the polished chrome coffee machine. Afterward, once again offhandedly, he looked down and checked his shirt and tie.

“Nice tie, Mr. Attorney,” Oved said. “What is it, Versace?”

“Thanks,” the lawyer said, slightly embarrassed. “Not really sure what it is,” even though he knew full well it was Ralph Lauren.

There was once a time when the lawyer knew he looked like an Arab. In fact, it wasn’t that long ago. His first year in university was the toughest of all as far as that was concerned. He was nineteen years old when he left his village in the Triangle and came to the university in Jerusalem. For all intents and purposes it was the first time he had left his parents’ home. He was stopped practically every time he boarded a bus – whenever he left the Mount Scopus dorms and headed toward the Old City, and again upon return. Nothing awful ever happened during those routine checks of his papers but standing there in front of the policeman or the soldier was always annoying, grating, constraining. But unlike other students in those days, who resisted the security checks, refusing to hand over their papers, butting heads with the policemen and the soldiers, charging them with discrimination and racism – assuming their stories were accurate and not mere bravado – the lawyer always forked over his papers with a smile. He was always courteous, wanting the policemen and the soldiers to know that he understood that they were just doing their jobs. The lawyer had always known that he was no hero and that he was not made for clashes, certainly not ones that could be avoided.

As his financial situation improved, he found he was stopped less. During his second year of school he got a job working at the law library and spent most of his paycheck on the kind of clothes the Jewish students wore. After he graduated, during his internship at the public defender’s office, he made a little more money and the security checks grew ever rarer. Then he passed the bar exam, opened his own office, moved to King George Street, and, for the entire five years of working there, had not been stopped once. Not by the police, not by the security guards who worked for the bus company, and not by the border policemen who patrolled the downtown day and night.