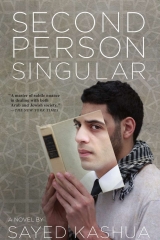

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

His wife took the bottle of water and the two glasses from Tarik and smiled.

“Thank you,” she said. “Sorry for the inconvenience.”

“No, not at all,” Tarik said in a voice that was gruff with sleeplessness and the residue of alcohol. “I’m going to head out in a second. There’s a café around the corner. Boss, I know what you want. A cappuccino, right?” he asked from the hall, still not visible to the lawyer.

“Yes, two shots, please.”

“And for the lady?” Tarik asked, referring to her as he always did. If only he knew the kind of things this lady was capable of, the lawyer thought.

“No, nothing, thank you. We’ll be leaving soon anyway, won’t we?” she said, looking at her husband and waiting for an answer that did not come.

“Okay, so two cappuccinos it is,” Tarik said and headed out.

The lawyer’s wife put the bottle of water and the glasses at the foot of the futon. “Would you please tell me what all this is about?” she asked. The lawyer sent her a combative glance and then drank long and hard from the bottle. Let her wait. Then he set it back down on the floor and looked her in the face.

“Where are the kids?”

“With Nili.”

“What did you tell her? That your husband got drunk and that you went out looking for him?”

“No, don’t worry. I didn’t say a thing. That’s what you’re always worried about, what they’ll think, what the neighbors will say.”

“Yes,” the lawyer said, “that’s what I’m worried about. What they’ll say is precisely what worries me, so lower your voice, please, there are neighbors here, too.”

“Okay.”

“So what did you tell Nili?”

“Relax,” she said, her voice sharp and challenging. “I didn’t tell her anything. I told her something had come up in the village. That you’d gone home and that I was heading up after you.”

“What kind of something?”

“I don’t know, I didn’t specify.”

“And she didn’t ask?”

“No, she didn’t ask. I’ve done a million favors for her over the years. So just relax, okay, no one knows anything. No one knows that you weren’t home last night and that you acted like a maniac.”

“Me?”

“Yes, you. And I’d like an explanation, too. Because I won’t live like this, not a chance,” she said, and she burst into tears and shut the bedroom door, which until then had been half open.

“Enough, cut the crap,” the lawyer said as his wife mopped the tears from her face.

“You’re insane,” she said, her face recomposed and fresh. “You are totally insane.”

“Lower your voice,” the lawyer commanded.

“What did I ever do to you? What did I do? You know what?” she said, holding on to the door knob, “you can take all your little conspiracies and shove them.”

“You’re a liar and an adulterer,” he said, trying to score some points. But again he felt that she had gotten the better of him, and with ease. All she’d done was pretend to turn her back and he had lost his cool.

“What did you say?” she asked, letting go of the doorknob.

“I said you are a liar,” the lawyer said, retracting part of his earlier statement.

“Why, exactly, am I a liar?” she asked, even though she had heard the other charge, too.

“I think you know well enough yourself.”

“No, I don’t. Please be so kind as to point out where and when I lied.”

“Listen, my love,” he said, trying to sound as belittling as he could, “we both know you lied. So why don’t we stop with the games, okay?”

“What, when did I lie? You don’t believe me that I went out for coffee with Faten?” she said, pulling out her telephone. “Then go ahead and call her. Ask her yourself.”

“No,” the lawyer said, the blood pounding in his veins. “Not Faten. You know full well when you lied.” He ground his teeth and wasn’t able to keep in the scream. “Enough. I’m not a little kid. You lied to me and you know it.”

“What? The note?” she cried. “That’s what all this shit is about?” She sat down and put her head in her hands, and the lawyer knew from experience that a confession was on the way. The question and the crying were the classic precursors to disclosure.

“Where did you even find that thing?” she asked, but didn’t wait for an answer. “Who gave it to you? Who’s the bastard who gave it to you? You think I even remember that I once wrote that? I recognize my handwriting but I really don’t remember writing it. What is it? It’s my handwriting, I recognize it, but what is it? Where did you find it? That’s what this whole thing is about? A note that I must have written a million years ago? Where did it come from?”

“What does that have to do with anything?” the lawyer groaned. “Why do you care how I got it or who gave it to me? You lied to me, that’s what matters.”

“How did I lie to you? You think I remembered that thing? I spent the entire night trying to remember what it was, when it was from.”

“And?”

“And I remember.” Her mouth was twisted into a sneer. “And you know what? If that’s what interests you, if this is the kind of thing that makes you act the way you did, then I’m the asshole for living with you for all these years.” She wiped at her tears. “Do whatever the hell you want,” she said, throwing open the door.

The lawyer jumped off the futon and grabbed her arm. “Where are you going?”

“I can’t live like this.”

“What will you do?”

“If this is what you think of me, I’ll do whatever you want, okay? You want me to go back to my parents? You want to separate? Whatever you want. Whatever you say.”

“So,” the lawyer said, tightening his grip on her arm as she tried to wriggle free and leave, “you’re using this as an alibi to go and run off with him.”

“With who?” she yelled. “You maniac, with who?”

“Lower your voice, please.”

“No.”

“Are these the kinds of power games you play with him, too? Does he like these kinds of games?” The lawyer envisioned them together, his wife moaning with the kind of pleasure he had never inspired, and on top of her this man, smiling with the slyest of smiles.

“You’re crazy,” she cried, her body slumping, no longer straining to get free. “You think I even remember what he looks like?”

“You remember, you remember,” he said softly, as though speaking to a little girl. He took her hands and lowered them from her face. He smiled at her, while his hands held on to hers and lowered them to her waist and suddenly he wanted to hug her, but instead of hugging her he raised his right hand and, had he not heard Tarik come in, would have smacked her across the face, sending her flying onto the bed. That was the language she understood, just like in her Egyptian melodramas, he thought, breathing heavily, his chest rising and falling, the thumping bass of the previous night pounding in his ears.

TWO CARS

Samah was not surprised to hear the lawyer on the phone on a Saturday.

“Good morning,” she said over her squealing kids and the high-pitched sounds of the cartoons. Once every few weeks the lawyer would call her on a Saturday with a favor, asking that she look into something, so long as it wasn’t too much of an inconvenience, and she, so long as none of her boys were sick and she had not gone out on a family outing, always had time to do the lawyer a favor.

“I’m looking for someone,” he said, and his voice wavered when he realized that he was including her in a matter of grave importance. “All I know is that he’s an Arab-Israeli, around twenty-eight years old. I need to get ahold of him, put him on the stand. He’s a social worker. Here’s the telephone number of the head of social services in east Jerusalem. According to the information I have, he worked at their substance abuse outpatient clinic six or seven years ago and then just disappeared. I know this is not very specific information, but for now it’s all I have. All I need is his name, unless, of course, you can also find where he works. That’s it. Nothing else.”

He read Samah the number for the head of social services, whom he knew personally, and then said, “By the way, Samah, if they ask who it’s for, say it’s for a law firm but don’t say which one. Say it has to do with an inheritance and that we can’t find a current address, okay? Thank you, and I’m really sorry to bother you with this, it’s just that it’s urgent, and please send regards to your husband.”

The lawyer snapped open his desk drawer, looking for something that would help his headache, sure that he’d find some kind of aspirin. His head throbbed, but he had preferred to go to the office rather than the house. “I have some work that I need to take care of,” he had told his wife, even though she had not asked for an explanation.

He got up to make himself a glass of Turkish coffee in the kitchenette and drank some water, in little sips, so that it would be readily accepted by his body, not big gulps that could be shocking to the system, as he’d read online. He heaped two tall teaspoons of finely ground coffee into a glass, poured steaming water over them, and stirred. Although the lawyer had read online that coffee only exacerbated a hangover, he knew he needed to be alert, to take care of business and to avoid mistakes. Over the past two days, he’d certainly made his share.

“I don’t remember his name,” his wife had said about the guy to whom she’d written the note. This, of course, was a lie. She’d told him the whole story and the lawyer had felt that while she described this man whose name she supposedly didn’t remember, there was compassion, even love, in her voice.

The lawyer sipped the coffee, scalding his tongue, and sat down in his chair. Again he wondered about the appearance of the man with whom he had shared his wife. Because even if she had been telling the truth and the man was really just a colleague, a downtrodden kid who had never so much as touched her – even if all that was true, the lawyer knew that love had blossomed between them. What an idiot he had been. He never even considered the possibility that his wife might have loved someone else before him, and now he wasn’t even sure if she’d ever loved him at all.

“What’s the big deal about the note? What did I say – that I’d had a nice evening and that he should call? That’s it,” his wife had said, after they’d supposedly made up, a reconciliation that began as soon as Tarik returned to the apartment. The lawyer had come to his senses, apologized, and said he believed her, and she had apologized too, saying again that she had forgotten that she’d ever written that note. She said that the whole thing had happened many years before, while she interned at the outpatient clinic. She’d written the note to another social worker, perhaps the strangest person she’d ever met.

“He was like a kid. And everyone took advantage of him. He was totally helpless,” she said, and the lawyer had a hard time bottling up the rage that the description evoked.

So it wasn’t a tough guy, a skirt chaser, but a sensitive guy, the kind who may well have read all the books that the lawyer had acquired at the used bookstore. But why Yonatan? the lawyer wondered. Why would an Arab sign the name Yonatanin all of his books?

“What was I supposed to think?” the lawyer had forced himself to say with a smile. He knew that temporary reconciliation was the only way to avoid defeat.

“Out of nowhere I find this letter, which I could tell you wrote, and I asked myself how is it possible that Leila, the person closest to me in the world, wrote this? I spent an entire day trying to find an explanation and when I couldn’t, I was hoping that you would give me one, but when you lied, I let the worst of my imagination run wild. As you can tell, I went out drinking, got terribly drunk, wanted to die. All because of a note you wrote a million years ago. Why didn’t you tell me?” he asked, and then without waiting for an answer he asked again, “Why didn’t you tell me?”

His wife laughed when he told her about the book. “Can you believe it?” he said and pulled out The Kreutzer Sonata.“Here I am putting the kids to bed, waiting for you to come home from your friend’s house, and I take out this book that I got at the used bookstore and the next thing I know I’m reading a love letter. At first I thought you had written it and put it in my book so I’d find it. But then. . I mean, how did you expect me to act? You should be happy all I did was throw your clothes out of the closet. I was thinking about burning them.”

His wife laughed, seemingly convinced. “I don’t believe it,” she said, turning the book over like someone examining a piece of evidence for the first time. “How did the note wind up in here?” and her question seemed genuine to the lawyer. “Well,” she said, “he was the strangest guy I ever met. He just disappeared one day. Everyone laughed at him, poor thing.” And that phrase, and the way she said it, only sharpened the sadness in the lawyer’s chest. “I guess you’ve always had a thing for strange people,” he said, giving her shoulders a squeeze.

They both thanked Tarik, and the lawyer apologized for the imposition and promised to make it up to him. Then he and his wife went out to their cars. She was going to pick up the kids and he said he was going home to shower.

“I don’t want the kids to see me like this. Did they ask about me?” he questioned her before getting into his car.

“I told them you were at work,” she said.

“Listen, wait, hold on just a second. . shut up, will you,” he heard Samah yell at her kids.

“Okay, I’m shutting up,” the lawyer said, and Samah laughed. “Hold on, I’m moving to the bedroom, I can’t get a word in here.”

“Okay, let’s hear it,” the lawyer said when she got back on the line.

“The name I got is Amir Lahab, that’s him.”

“You sure?” The lawyer wrote the name down on a piece of paper. Amir Lahab; he mumbled the name to himself and then lit a cigarette and tossed the lighter onto the desk. “Who gave you his name? The head of social services?”

“Yeah, I called him and he told me right away. He just burst out laughing as soon as I told him that I was looking for a guy who had worked there and then disappeared. ‘There’s a blast from the past,’ he said, laughing the whole time. Turns out that this Amir worked under him and that he’d been Amir’s supervisor during his internship. He made a good impression, apparently, and was a good kid, a little weird, but he did his job well and he kept to himself. He started working there right after he graduated. Worked for a few months and then one day he left a resignation letter and disappeared.”

“Disappeared? But that was many years ago.”

“Right. Several years ago,” Samah said. “That’s what the guy said. He said he hopes I’m able to find him and that after he left his job they looked for him for a while but he never turned up. He told me to send regards if I found him.”

“And then?”

“And then I asked if, by any chance, he had an old address or something and he said he’d look in his file and he found an address in Jaljulia, an old telephone number, and an ID number.”

“Oh, really? What’s his ID number?” the lawyer asked, practically leaping out of his chair.

“I wrote it down in the kitchen. I’ll text it to you in a second.”

“Great, Samah, thank you so much,” the lawyer said. “And please apologize again to your husband. Tell him I’ve got some cigars here with his name on them.”

So that’s his name, Amir Lahab. The man his wife had been with – and who knew what they had done – on the night that he, the lawyer, had fallen in love with her. He recalled how she had surprised him and his sister when she came home early from the student party. She had probably been out dancing with Amir Lahab, the lawyer thought, remembering her black dress and the expression on her face when she came back to the dorm. Her face had looked sad, and he, the idiot, had loved her all the more for it. Later that night he had been unable to fall asleep. He kept seeing her at the entrance to the room, in that dress, radiant, and all he could think of was how he could make her his. She, too, probably hadn’t been able to sleep that night, but not on account of him. Probably all she could think about was Amir Lahab and the wild night she had had with him, which led to the letter, which was not a letter you write to just any old colleague – of that the lawyer was certain. It was a love letter. He disappeared, she had told him, she wrote him that note and he disappeared. She swore she hadn’t seen him since and that she couldn’t even remember what he looked like.

“If I saw him on the street, I wouldn’t recognize him,” she had said, and the lawyer knew you did not have to recognize someone in order to love them. The lawyer realized that she had settled – for him. What would have happened had this Amir not run off? He remembered the early weeks of their courtship and felt humiliated. She wasn’t thinking about me at all, he thought, she was waiting for someone else. She was stimulated not by my presence, but by his absence.

Amir Lahab,the lawyer typed into the search engine, at first in Hebrew, which read it as Lahav,and he found thousands of links. Designers, lawyers, carpenters – there was a long list. He typed it in along with the words social workerand got nothing relevant. Still, he clicked on several links and was surprised to find that all of the Amir Lahavs were Jews.

Then he typed the name in Arabic and found that most of the results were from different countries. The ones that were from Israel did not seem remotely related to social work.

The lawyer reverted to the tried-and-true method of locating an Arab in Israel – using the family name. He typed Lahabinto the Yellow Pages search engine and found that they were a big family in Tira, not in Jaljulia as Samah had said. In Jaljulia there were no Lahabs at all. Both villages are in the Triangle, and Tira was very close to the lawyer’s own hometown. He’s from the Triangle? the lawyer wondered. My adversary is a villager? The man who had read more books than he, the one his wife had preferred, was a lousy villager, just like him? The lawyer tried to calm himself. Say she really did love someone before him? Say she had fallen for one of the boys in high school? Would he be jealous then, too? Wasn’t he just being primitive? What had happened to his progressive ideas? What happened to women’s rights? What about his daughter? Hadn’t he promised himself a million times that she would grow up differently? That he would shield her from societal expectations and norms and that he would raise her as a liberated woman?

The problem was that the lawyer knew he was not willing to be different. If it was common, if his friends and family members were married to women who had all had prior relationships, that would be one thing, then he could deal with it. But he was not willing to be the only joker in the group. And anyway, the lawyer wondered, why had she hid this relationship? If she believed she did nothing wrong, then why had she lied? Was she embarrassed of what she’d done, did she feel it was wrong, so wrong that she had hid the truth from her husband, and if that was the case, then why should he accept it now?

The lawyer found no Amir Lahab in the telephone directory. He chose one of the Lahabs in the phone book from Tira and called from the unidentified number in the office. A child, he couldn’t tell if it was a boy or a girl, answered the phone.

“Who is this?” the little voice asked. “Who’s speaking?”

The lawyer asked to speak with the child’s father and the little voice giggled and handed the phone to the mother.

“Hello.”

“ Salaam alaikum,” the lawyer said, and the mother’s voice changed when she realized it was not someone she knew.

“ Alaikum a-salaam.How can I help you?”

“I’m looking for Amir Lahab,” the lawyer said.

“Who? There’s no one here by that name. I think you have the wrong number.”

“I’m a lawyer from Jerusalem, and I thought you might be able to help me find him. Maybe he’s a family member?”

“Hold on,” the woman said, and she yelled, “There’s a lawyer on the line and he says he’s looking for someone named Amir Lahab from our family. You know any Amirs?”

The lawyer could hear her husband walking toward her and taking the phone.

“Hello, who’s speaking?”

“ Salaam alaikum,” the lawyer said, using the greeting he always used when he wanted to set someone at ease.

“ Alaikum a-salaam.Who’s speaking, please?”

“I’m a lawyer,” the lawyer said, and gave the man a name he had made up on the spot. “I’m handling an inheritance case and I’m looking for someone by the name of Amir Lahab. I thought he might be from your extended family and that perhaps you could help me find him.”

“Amir,” the husband said. “I know an Amir, but he’s a little kid. In first grade.”

“No, that wouldn’t be right.”

“Oh,” the husband said, “maybe it’s that Amir, the son of. . wait a second.” He called to his wife, “Do you remember what’s her name’s son, you know, Abu Hasan’s daughter, the widow, the one who left, what’s her name?”

“Meissar?” he heard the woman say. “I think she had a kid but I don’t remember his name.”

“It’s possible,” the husband said. “Might be him. If I’m not mistaken, he doesn’t live in Tira anymore. They left when he was a kid, he and his mother, there was a whole big mess and they left. Might be the guy you’re looking for.”

“I see. So they don’t live in Tira?”

“If it’s them, I really don’t know where they are. I think they may have moved to Jaljulia back in the day, the mother and the son. But I’m not sure.”

“To Jaljulia,” the lawyer said. “Thank you so much for your help, sir. Thank you.” The lawyer hung up the phone and typed Jaljuliainto the space on the Web directory where it asked for place of residence. He didn’t find any Amirs but he did see a listing for a Meissar La’ab. He knew that was the person he was looking for, even though the name was slightly different. The Israeli authorities regularly bastardized Arab names.

The lawyer dialed the number. His heart thumped and he tried to organize his thoughts. What if he’d moved back in with his mother? What if he answered? He decided he’d hang up immediately if he heard a male voice. Maybe he’d ask, “Amir?” and then, if the guy said something like, Yes, who is this?, the lawyer would end the conversation.

“Hello,” the lawyer said to the voice on the other end of the line, but it was a recorded message: “The number you have reached is no longer in service.”

95 OCTANE UNLEADED

What exactly was he planning on doing? What would he do if he found out where Amir Lahab lived? The roads were relatively empty on Shabbat and he could make the drive down to Jaljulia in around half an hour. The lawyer felt the need to make the trip even though he wasn’t sure he’d get out of the car. He couldn’t stay in the office and he had the feeling that a drive on the open road would do him good. Sometimes driving alone in the new car had a therapeutic effect.

There were only a few cars waiting at the light on the way out of Jerusalem. A picnic Saturday, the lawyer thought, as he looked over at the family in the car to his right. He liked it when drivers eyed his car, liked it when he spotted women looking at him through their sunglasses, trying to guess what the rich man in the luxury car did for a living. But right now all he felt was jealousy for the family to his right. He saw the woman talking away at her husband, maybe even arguing, and he recalled the way his wife would hold her silence for long stretches of time when they were in the car together. She could keep quiet for hours, and it always pissed him off.

“Say something,” he’d plead whenever they were on their way to his or her parents or just en route to some fancy hotel with the kids for the weekend. And she’d always respond, “What do you want me to say?”

The lawyer hit the gas and headed away from Jerusalem, leaving the family car far behind. They want a show? He thought to himself, I’ll give them a show, and he remembered his first time on the highway with his daughter. She was a month old and his wife was in the back with the baby and the lawyer drove more slowly than he ever had in his life. He was sweating and his sweaty hands grew slippery on the wheel and he was afraid of losing control of the car. He stuck exclusively to the right side of the road and pumped the brakes whenever he had to slow down. He despised the car he had at the time, felt it was not to be trusted, that at any moment a tire could blow out, that the brakes could betray him at any turn, sending him and his family flying off the cliff. The lawyer shook his head free of those thoughts now and played with the buttons on the steering wheel, looking for talk radio, anything but music, anything that would take his mind off the matter at hand. But he found nothing.

What was the point in going to Jaljulia? The lawyer was not sure. Maybe it was his wife’s innocence that he sought. Maybe he wanted to know that the woman with whom he had not shared a bed for many years still loved him, even though he was not sure to what extent he loved her. Maybe he wanted to breathe life into the embers of his love – he’d read of such things – but he knew that at best the embers were extinguished and at worst had never been lit in the first place.

Or maybe he sought to retrieve his own honor. What was it that he wanted? To know that she’d cheated on him or to go back to living the way he had before he found the note? Maybe it was for the best that his life had been disrupted. Maybe it was a sign from above, he thought, even though he had never been one for celestial signs. Maybe it was time to pack his things and go, maybe it was time to stop sleeping alone in his daughter’s bed and start fresh, do everything differently, pick the kind of woman who would, as he imagined in his most melancholic moments, finally light the fire of love within him. The lawyer recalled an article he’d come across in which some important psychologist had said that love meant loving someone more than you loved yourself. Someone that completed you. Love is the ability to sacrifice for the object of your love, was the psychologist’s point. While reading the article, the lawyer had asked himself if those were his feelings toward his wife, and it pained him to admit that they were not. She did not complete him. On the contrary, he felt that married life limited him – financially, because he had a family to support, and professionally, because without the need to support them he might have gone back to school and pursued an advanced degree, perhaps a PhD, and become a professor, as he’d once wanted. At any rate, he didn’t want to sacrifice anything for her, that much he was sure of. But what did she lack anyway? he asked himself all of a sudden. After all, I give her whatever she wants. She has never wanted for anything. He remembered that the real matter at hand was her love for him, and not his for her. Does she sacrifice for me? the lawyer asked himself, and responded that it was not so.

Maybe at some point he really would come across what they call a soul mate. Maybe now that he was older, more organized, more aware of his wants, more in control of his thoughts, he would be able to discern between temporary lust and sustainable love. Maybe now he would be able to find a woman he could sleep next to every night, maybe he would feel the warmth of her body seeping into his bones, granting him a tranquility he had never known. The lawyer saw before his eyes a faceless woman, but he knew she had the face of an angel and she slept peacefully in his arms, her face smooth, a happy sheen across her cheeks. He imagined them sleeping harmoniously together, completing one another in their sleep, too, wrapped in a comfortable embrace, moving their bodies with complete synchronicity, always fitting together. For a moment he felt a rush of warmth in his heart. Maybe all of those romantic poets were right? Maybe he shouldn’t have been so dismissive of their words? Maybe he shouldn’t have been so skeptical of what was clearly a sublime sensation?

She, on the other hand, had never been skeptical. She was willing to lie, to live in sin, to risk her good name, the name of her family, the future of her children, all for a love she could not get from her husband. For a fleeting moment the lawyer admired his wife for her courage but the admiration quickly faded into hatred and contempt. His wife – she wasn’t smart, the lawyer thought; at best she was a functioning airhead. A miserable little Arab woman whose guides in life were love songs and filth-ridden melodramas. Only the lower classes were capable of falling blindly in love after adolescence, the lawyer thought, only the poor, the uneducated and unenlightened, could fall helplessly in love. Like animals, the lawyer said to himself, acknowledging, not for the first time, that there was no bridging the divide between their backgrounds, between where he came from and where he had found her. You must have to be primitive in order to continue believing in the delusion called love. It’s a lot like religion, the lawyer thought, it’s easy for them, the down and out, to embrace it.

He surprised himself with these thoughts. If that’s how I perceive her, he thought, then she must be aware of it, and for a moment he practically condemned himself for her decision to seek solace in someone else’s arms. But that’s not how it is, he said to himself, cutting the chain of thought, by God that’s not how it is. He might be busy, he might not love her as he used to, but he did not ignore her or forsake her or make her life unduly hard. She was just as preoccupied with life as he was. How could she ever find time to think, strive, desire? Who even had time to cheat?

His wife had a good life, he concluded, and mine isn’t too bad either. It had been a little bit boring, but by no means dreadful.

A sign missing a few of its letters in Hebrew and Arabic welcomed him to Jaljulia. The lawyer decided to stop at the gas station at the entrance to the village. He’d never been to Jaljulia but he had known, ever since he had been a kid growing up nearby, that it was even worse off than the surrounding Arab villages, which were the kinds of places he learned later in life to call disenfranchised. In college, for instance, he had never once met a student from Jaljulia.