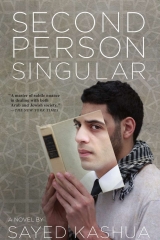

Текст книги "Second Person Singular"

Автор книги: Kashua Sayed

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

“You’re walking too fast,” Leila said. “We’re not late, are we?”

“Sorry,” I said, turning around. I hesitated for a moment, my eyes focusing in the general vicinity of her face, and then looked her straight in the eye. I blushed and felt my face burn and hated myself for it, wanting to run away.

“You’re so shy,” Leila said, smiling.

Where the hell did she get that from? I thought to myself. But I liked it. I saw it as a kind of understanding, a sense of trust, a lack of fear. Sometimes, when I heard my colleagues or even Majdi talk about girls, I was sure that if I was a girl I would be terrified of every man in the world. I walked slower, but still one step ahead of Leila so that no one would think we were together. I could’ve led us through the side streets and alleys that link Wadi Joz to the Old City but I chose to take the main road so that there’d be witnesses, so that we wouldn’t be alone. We got to Salah al-Din Street and from there to Musrara. I tried walking slowly, at her pace. As we prepared to cross the street from Musrara to Damascus Gate, we stood close to one another and she said, “You’re different from all of the rest of the guys in the office.”

I crossed the street fast and Leila ran after me.

There were faces that I recognized at the entrance to Damascus Gate but I lowered my gaze and ignored them. Some of them were selling toys and perfume and others were just leaning against the stone walls. As we entered the Old City, I drew close to Leila and said, in a professional whisper, “Damascus Gate is one of the biggest drug-dealing zones in the city.” It was a Wednesday, still early in the morning, and the foot traffic in the market was thin.

“How long will it take us to get there?” she asked, looking at her watch.

“Five minutes.”

“Then we have some time,” she said. “Do you think we could go to Lina? I haven’t been there in a long time.”

Lina’s ground-floor seating area was full. The waiter pointed us upstairs and we found a table for two. I shouldn’t have agreed to this, I thought. Leila flashed her smile, which I saw out of the corner of my eye. For some reason it seemed to me that I was making her laugh. The big city girl from the Galilee must’ve thought that I was a walking stereotype from a small village in the Triangle: the kind of guy who is embarrassed by the presence of girls. After all, she didn’t know how they talked behind her back. I still remember a joke about a guy from the Triangle who asks a Christian girl from the Galilee if she’d like to dance, and she says, “Your name’s Muhammad, you’re from the Triangle, and you want to dance with me?” For some reason I was sure that Leila was a Christian, even though, as opposed to the other Christian students I had met, she did not wear a cross. Many of the Christian students wore one over their clothes, displaying it so that everyone would know: I’m not a Muslim, not really an Arab.

We both ordered our hummus plain, no chickpeas, no fava beans. “Mmm, I love Lina,” Leila said, scooping the hummus out of her bowl with a pita. I watched her hands work: she was not one of those girls who patted some hummus on a pita with a fork. She held the pita and she shoveled the hummus into her mouth. Holding an onion wedge, she asked “Do you mind?” and took a big bite. “What are you doing?” she asked. “Why aren’t you eating?”

“I’m not hungry,” I lied. The truth is I didn’t eat because it seemed to me at that moment that it was embarrassing, beastly, the kind of thing that should be done alone, behind closed doors. Definitely not in front of a girl and definitely not in front of a girl for whom I already knew I felt something, despite my best efforts to keep that feeling at bay.

“I’m not hungry, but I’ll have a little,” I said, and I tore off a modest piece of pita and dipped it into the deep bowl. I bowed my head and put it in my mouth, chewing carefully, with my mouth shut, trying not to make any eating noises. And I immediately took a napkin and mopped up around my mouth. When I eat, it always seems to me that the food is smeared all over my cheeks and across my whole face.

Skinny, curly-haired Leila with her small delicate face finished her hummus fast and asked, “So, are you going to eat all of yours?” and when I shook my head no, she pulled my bowl over and ate it, too, this time with a fork and no pita. When we were done we paid separately.

Our destination was the Aluwad neighborhood, the home of Shareef Abu-Siam, Leila’s addict.

“Where are the Abu-Siams?” I asked an old salesman who was sitting in a wicker chair in front of the neighborhood grocery store. He pointed at a green gate, behind which we could hear an entire clan of children. Ten children met us at the entrance and an elderly woman, whose hands were busy with her hair covering, shooed them off and asked, “Are you from social services? Welcome.” The small courtyard was trapped between rooms and walls, and cement stairs descended from the upper floor in all directions and seemingly without any logic. Some of the rooms on the upper floors were unpainted and unfinished and the windows and doors were wide open. “Coffee or tea?” the old woman asked.

“No, thank you,” Leila said. “Are you Shareef’s mother?”

“Yes,” the woman said, and immediately called out three names. “These are his kids,” she said as the children clustered around her. “Two boys and one girl, and the infant’s in his mother’s arms.” The woman pointed to one of the doors. “That’s Shareef’s house. He’s not home, just his wife’s around. God only knows where he is. He was once as strong as a convoy camel. Inshallahyou will be able to help, my children,” she said.

A young woman opened the door to Shareef’s house. “Please,” she said, “come in. It’s cold outside. Son,” she added, “go bring chairs.” Her son ran downstairs and came back with white plastic stools from the courtyard and set them down in the small room, under the light of a single bare bulb. A kerosene heater burned in the middle of the room. Mattresses were stacked in the corner and, on a small pallet near the stove, the baby slept.

Shareef’s wife looked to be less than thirty. She was wearing loose green sweatpants and an old sweater, and she sat opposite Leila, answering her questions with tired eyes. Shareef leaves early each morning. It’s not clear where he goes. He says he’s going to work, but he never comes home with money. He comes home at all hours. And he only comes home when he’s high and has another hit for the morning. Sometimes he pulls out a spoon, a lemon wedge, and a lighter right in front of the kids and starts preparing his hit. He’ll tie off and stick the needle in right in front of the kids. The young woman held a napkin in her hand and dabbed at her eyes and nose as she spoke. Leila sat before her with a pen and paper and nodded her head. She asked more and more questions, mostly about the kids, with surprising proficiency, unrattled by the tears, speaking softly but without pity.

The children don’t go to school anymore, Shareef’s wife explained. They weren’t even enrolled this year. Why should I sign them up? Last year I did but they never went to class, just spent all their time roaming around the Old City. According to the neighbors, her eldest had been seen begging near Jaffa Gate, where the tourists congregated, and outside the mosque. Might as well stay at home, she said, it’s better than having them out on the street. The oldest one was arrested for trying to steal a tourist’s bag and that was before he even started third grade. The younger ones try to do what he does, they copy him. According to her friends, there are boarding schools for kids like hers and she used to think it was impossible for a mother to send her children away and not see them every day, but now she knows it’s the only thing that will save them. “As long as they’re put in a good place,” she said. “At least that way they’ll have a clean bed, food, and an education. Maybe they’ll even learn a trade or something. If they stay here they’ll end up just like their father, who’s never ever going to stop using.” Her husband’s older brothers had locked him up in his room several times, keeping him there for days on end, swearing they wouldn’t let him out till he kicked the habit, and he would yell, beg, and cry like a baby but they didn’t give in – till they got tired of the whole routine. Then they’d let him go and soon enough he’d disappear again, returning home a day or two later, high as a kite.

Shareef was the youngest of five brothers, his wife said. All of the brothers had left the neighborhood. They owned houses in Dahiyat al-Bareed or in a-Ram, and lived there with their families. Shareef was the only one who had stayed on in his mother’s house after he got married. Her mother-in-law, said Shareef’s wife, lived in one room and they had the run of the other three. But the new residency law brought all the brothers back to their mother’s house. None of them wanted to risk losing their national health insurance, their free educations, their blue identity cards. So they came back with their families and now all we have is one room, she told Leila, and then because they didn’t have enough space they built two extra rooms upstairs and now the city says it will demolish the rooms because they were built without a permit, so now we have a whole legal battle, a whole other mess. In the morning, she said, blowing her nose, I stack the mattresses, and in the evening I lay them back out. Everyone lives in this one room, just like this.

Leila walked back to the office with her head bowed. She said nothing. When we got there, she asked me to remind her of the clerk’s name at the welfare bureau and before leaving the room she asked me which boarding school was considered the best for at-risk kids.

CORDUROYS

I recall the smell of Yonatan’s clothes. Somehow they held on to the good smell of the fabric softener and not the medicinal scent of the attic.

I showed up at Scout Street an hour before the beginning of my shift and hesitantly asked Osnat if it would be okay to come a little late the following evening.

“What time will you be able to come?” she asked.

“I’m not sure, but no later than midnight. Is that okay?”

She smiled. “It’s only okay if it’s because of a girl.”

I blushed and let a stupid grin creep across my face.

“ Sakhtein,” she said, turning to Yonatan and raising her voice, “at long last our shy friend has found someone. See!” then she turned back to me and asked for details.

“An intern at the office,” I said.

“How old?”

“Twenty-one.”

“Name?”

“Leila.”

“Pretty?”

I nodded.

“You’re so cute. Where are you going?”

“To a party. . at the Hyatt. .”

“And what are you going to wear?”

I shrugged. “I’m going like this,” I said, pointing to the clothes I had on.

Osnat shook her head. “No, you’re not. I hope you don’t take this the wrong way, but you’re not going like that. You’ll scare her away.”

I had never thought about clothes before. I had never bought anything for myself aside from underwear and socks, and those I had gotten at the flea market outside Damascus Gate. Every once in a while I’d come home and find that my mother had bought me a new pair of jeans or a shirt or some sweatpants. Before I left for college, she bought me a new wardrobe, clothes that were suitable for the cold Jerusalem winters.

Osnat opened Yonatan’s closet and said, “Let’s see what we can find here for you,” and I was flabbergasted by the sheer volume of clothing. I had never opened that closet before and somehow I had figured that it held nothing but additional sets of pajamas. Instead, there were dozens of ironed, bright-colored shirts on hangers and alongside them a dozen pair of pants. The shelves were covered with stacks of T-shirts, arranged by color, and everything was clean and straight, not a single shirt out of place.

“You’re Yonatan’s size,” Osnat said. “He has so many beautiful clothes. Don’t you, Yonatan?” she continued, looking over toward his bed. “And you don’t mind loaning a few things to our friend here for a date with his girl, do you?” She’s not really my girl, I thought, all she did was invite me to come to the Arab students’ spring semester party. On the other hand, it was going to be the first time I would see her outside work. A part of me was excited by the prospect, but most of me was scared.

Osnat flipped through the shirts and chose a black one with a starched collar. “Black will work well with your pale skin,” she said. “Now, let’s see what else we need. . no, no jeans, I’m sure she’s pretty sick of seeing you in the same jeans every day. . Oh, here, this could work.” She pulled a pair of corduroy pants out of the closet. They were what she called “off-white” and they had a matching jacket with brown leather patches on the elbows.

“Come on,” she said, “try it on. I want to see how it fits.”

“No way!”

“Shut up and change. Go, put it on, I’m in a rush.”

The pants were a perfect fit. They were just right in the waist and length. I tucked the shirt in and put on the jacket. Osnat smiled from ear to ear when I came out in Yonatan’s clothes. She turned me this way and that, walked over to the closet, and returned with a brown leather belt with a wide rectangular buckle. I threaded it through the belt loops of the pants and while I did that, Osnat went back to the closet and pulled out a pair of brown leather shoes. I saw five pairs of dress shoes and three pairs of sneakers. “These are about a thousand times better than your white sneakers,” she said, pointing at the new-looking shoes. She looked me up and down and then pressed the tip of her thumb to the tip of her index finger, drawing a circle with her fingers and announcing, “Perfect.”

“This isn’t me,” I said. I felt like I’d been stuffed into a costume.

“It is totallyyou. This is what you’re wearing to the party. You look great. There’s no reason for you to put those work clothes back on.” I liked hearing that I looked good. The things Osnat said gave me some hope and for a moment I really did feel like someone else, just what I’d always wanted to be.

“You know,” she said, “it’s not just that you’re the same size as Yonatan. As soon as you came in with Ayub I felt this kind of tightening in my heart, felt at ease with you, as though I’d known you for years and only later did I realize why. You look like him, did you know that? The two of you are practically identical. Don’t you think, Yonatan?” She took her bag, wished me a good shift, and said good-bye to the two of us.

THE SOLES OF OUR SHOES

I got back early from the party. By about ten thirty I was on Scout Street, opening the door to the house and trying to walk on my tiptoes so that Yonatan’s thick-soled leather shoes wouldn’t make any noise. I froze when I saw Ruchaleh out of the corner of my eye. She was sitting in the dining room. Sometimes I forgot she even existed. My heart thumped wildly as I stood there, in an outfit that belonged, in its entirety, to her paralyzed son.

“Good evening,” I managed to say to her, stuck to my spot on the floor. She was sitting at the dining room table, surrounded by folders and papers and an open bottle of liquor. I saw her look me over from top to bottom. She nodded, said nothing, refilled her glass, and went back to her paperwork. I went up the stairs, still trying not to make noise, to Yonatan’s room.

Osnat was sitting on the couch reading a book. She looked at me and then back at her watch.

“What happened?” she whispered. Yonatan was asleep.

“Nothing,” I said. “Everything’s fine.”

“You sure? You don’t look so great.”

“Ruchaleh is downstairs. She saw me in Yonatan’s clothes.”

“So what,” Osnat said. “She doesn’t care. Besides, at this hour, with her drinking, she doesn’t notice a thing. Relax. And if it makes you feel better I’ll talk to her and tell her it was all my idea. Even though it’s totally unnecessary. Believe me. She’s a good person. She understands. Do you know how many years she spent protesting with the Women in Black?”

As soon as Osnat left, I took off the clothes, shoved them into the washing machine, and put on the T-shirt and sweatpants I’d left in the staff closet. I stood in front of Yonatan’s CD collection, which I had begun to enjoy more with each shift, and decided on Lou Reed’s Berlin. I slid the disc in and fast-forwarded to the song about the mother whose kids are taken away, the one that ends with the sound of wailing babies. I flipped Yonatan over on his side so that he was facing me. I lay down on the recliner and listened to the music. Then I took Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonataoff the shelf and tried to focus on the text. I didn’t want to remember any part of the party.

Leila had worn a long black dress and a wool jacket, high heels, and just a touch of makeup. The only thing I’d seen before were her hoop earrings, which she’d worn once to the office. She breezed past the guard outside the dorms and smiled at me. I think she was a little bit shy about her outfit, maybe as much as I was about mine.

“Hey.”

“Hey.”

We walked down the road together, toward the club at the Hyatt – it was called the Orient Express – maintaining a safe distance between one another, not saying a word. The only conversation between us was the clack of her heels and the squeak of Yonatan’s leather shoes. Her scent wafted toward me. I looked down, trying to quiet the unrecognizable feelings inside me. What is she feeling right now? I wondered. Does she feel regret, like I do? Why is she not the same easygoing, funny Leila, the rambling Leila I hung out with yesterday in the office?

“Leila,” I said, realizing it was the first time I had said her name aloud. I didn’t even know why I said it, maybe I just wanted to speak her name.

“What?” she asked, turning to me. I shook my head, showing I didn’t really have anything to say, and I looked back down at the sidewalk.

Leila insisted on reimbursing me for the tickets but she let me buy her an orange juice. I got myself a Coke. We were among the first people to arrive at the club. The music of Wadih El Safi played in the background but no one danced. We sat next to each other and still said nothing. Breaking her usual habit, Leila did her best to avoid my gaze. A considerable amount of time passed before she spoke.

“I’m sorry that I’m acting this way, but you have no idea what kind of interrogation my roommate put me through when she heard I was going to the party. She acts like a police officer, watching my every move, listening to everything I say, and reporting back to my parents afterward. She’s disgusting. I can’t stand her. ‘Are you going alone? Who are you going with? Why are you going, anyway? Don’t you have work to do? What are you wearing?’ It’s my first college party, I bought the clothes today. I went to the mall and got the dress. I’m twenty-one years old, can’t I get some clothes and go to a party? Who does she think she is?”

The club started to fill up. Compared to what the students were wearing, I started to feel underdressed. I had never seen this side of campus life. I didn’t know anyone other than my roommates when I went to the university. Leila’s mood improved, she smiled and started talking more. “I just hope my roommate doesn’t come in here looking for me with her hijab,” she said, laughing. I felt good. The place was crowded and loud and the music started to get more rhythmic. More and more couples moved onto the dance floor. It started with Shadi Jamil, classic high-country stuff, then Sabah Fakhri, and from there to some very danceable Egyptian pop. It was obvious to me that Leila wanted to dance. She was moving to the music and singing along. I didn’t recognize most of the songs, which surprised Leila. “What, you don’t know who Amr Diyab is?” she asked.

I don’t know how to dance. I’ve been to very few weddings, and that’s where everyone learns to dance. In Jaljulia no one knew us well enough to invite us to any weddings, and in Tira we were simply not invited. I stood on the dance floor, not moving a muscle, while Leila moved gracefully before me. She smiled the whole time and it did not seem that she minded that her partner was just standing there like a lump of clay. Slowly I managed to convince myself that no one was watching me, that everyone there had something better to do than watch me dance, and I began to move my body. I imitated what the men around me were doing and I kept a safe distance from Leila, reminding myself that she was a colleague. All of a sudden I froze, realizing that someone was watching me. The guy next to me moved, and past him I saw Khalil. He raised a bottle of beer, offering me a silent cheer, and then burst out laughing. Shadi and Walid were sitting beside him. I didn’t move. I could just hear their comments and their sniggering. I could read the ridicule in their eyes. Leila noticed that something was bothering me, looked over at their table, and then turned back to me, still dancing, and made a who cares?shrug with her shoulders and a scrunching up of her face. She tried smiling again and went on dancing but she realized that I was no longer there, on the dance floor at the Orient Express. Five minutes later I told Leila I was leaving, and did not wait for a response.

Leaving Yonatan’s place and walking toward the bus stop on Herzl Boulevard, everything became clear. Enough. This cannot go on. I’ll put an end to it today. I had a clear vision of exactly how I was going to change my life. Images of the revolution played in my mind. I was done turning the other cheek. Why should I let those jerks dominate me? How had I let myself be so stupid, leaving Leila like that?

Ruchaleh’s white car pulled into the bus stop. “You going to the office?” she asked.

“Yes, thank you,” I said and got in.

If she says anything about the clothes, I won’t so much as apologize, I told myself. I’m done being scared. Completely done. If she says one word, I’ll get out of the car and never come back to her son’s stinking attic. I don’t need this crappy job.

But Ruchaleh did not mention clothes. She said nothing the entire time. She drove quietly, as always, her face very much like Yonatan’s, her gaze, like his, fixed nowhere and everywhere. In my head I heard Metallica’s slashing guitars, my soundtrack for the morning’s revolution. I imagined myself in the office, standing tall, head and shoulders above everyone else, yelling, putting them back in their places, and they, my colleagues, cowering, silent, the smiles wiped off their faces, understanding that their days of toying with me were over. Or maybe I should forget the office and go straight to Leila’s dorm? I’ll buy flowers and wait for her by the entrance to the building. I’ll stand there for all to see, even her roommate with the hijaband I’ll give her the flowers and I won’t even whisper when I say, “I love you.”

“Thank you,” I said to Ruchaleh as she pulled the car up to the front of the building. I walked differently. I could feel it in my feet and hear it in the sounds of my shoes. I felt like a new man, strong, proud, unafraid, marching toward a revolution with a spade in one hand and a rifle in the other.

It was eight in the morning and I had a solid two hours before anyone would come into the office. I imagined Khalil coming in first, smiling at me and saying, “What, just like that you leave a girl hanging?” I won’t say a thing to him. Not a word. I’ll wait for everyone to show up, wait for them to start their day, their usual gossip and sniggering, and then, when they pull out their change for the breakfast run, I’ll throw it back in their faces and launch my attack. I won’t be defensive in any way. I’ll stay on the attack, my face burning with rage. I’ll show them who’s a wimp. I’ll show them how lame it is to think every girl in the world is just a pair of legs and an ass. I don’t care if Walid’s there or not. I won’t yell at him, but I’ve got no problem letting him hear what I think of my colleagues. I could see them sinking into their chairs and me going back to work as though nothing had happened, my chest threatening to burst with pride.

“A battle,” I heard my mother’s voice say, just as she did whenever I stood before her, bruised but not crying, and she knew I had been beaten up again on the way back from school. “A battle,” I could hear her say, “is like when two people bite each other’s fingers. It hurts both of them but the loser is the one who admits it first.” (Only later did I learn that she had been quoting from some Vietcong revolutionary whose book she had on her shelf.)

I remembered that sentence well, even though it had never been relevant to me. I never felt like I was biting anyone’s finger; it was only my finger in my adversary’s mouth and I never thought there was any chance that he would cry out before me. I never fought back. I just tried to deflect the blows as best I could and then run away. Just like my mother, who ran away, too, years before I ever had to, and who explained that she had done it because of me, for me, because she didn’t want me to suffer, to feel unwanted and alienated. Later she told me that she didn’t run away so much as sneak me away, just as she did again in the middle of the school year in elementary school when she heard that I was being picked on, this time smuggling me into a Jewish school in Petach Tikva, using every last one of her connections with the teachers union. I went to that school for two years and I liked it a whole lot better. No one told me that my father had murdered anybody or that I was the son of a collaborator. The kids simply did not speak to me and I did not speak to them. I was good in school, though, and soon enough I learned the language, learned to speak like them, and even started writing better than most of them.

When Mom made me go back to Jaljulia for junior high, I started to cry, but she said it wasn’t up to her, that the school guidance counselor had said that I wasn’t getting along in Petach Tikva, that it was not the right place for me. In junior high and in high school I was no longer beaten up, because my mother was a teacher at the school and she kept a close eye on me. Twice a day at least she would come into class and ask how I was doing. That’s when I started to keep my distance from her and today I regret that I can’t so much as imagine a hug from her.

Five minutes after I arrived at the office, the images of the revolution started to fade. I remembered that it was Leila’s day to come into the office and that she would be in soon. I left the room, locked the door, told the janitor that I wasn’t feeling well, and asked him to tell Walid that I had gone to the doctor. I punched my card and left. That evening I left for Scout Street half an hour early. I got off the bus near the courthouse and walked in the dark to the empty office, holding an envelope and a printed letter. The text was short. Beneath the date and the subject I had written, I quit,and beneath that I had scribbled my signature. I knew that no one would come looking for me. I pushed the envelope into Walid’s mailbox.

In my box I saw a small piece of paper. It said, I waited for you, but you didn’t come. I hope everything’s all right. I wanted to thank you for last night. It was wonderful. Call me tomorrow?