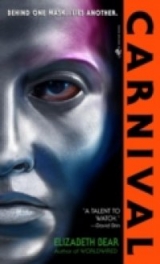

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

“Before the Governors? Sometimes.”

“It must be better now,” she said. “From what I’ve read. But still, the price.”

“Too much.” Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones. The futility of his own name stunned him. Five meaningless words. Five cultures, five entire racesof people. And all that was left of them, the living rememberer of all those millions of dead, was the syllables of a Liar’s name.

He swallowed. It hurt.

Her fingers brushed the wall again and fell away from the black granite. “It’s lunchtime,” she said. “I understand you have some dietary restrictions to consider. Shall we see what we can find to eat while the staff rearranges the display? We’ll come back to it after.”

“I’d like that.” He looked away from the wall, which was a mistake, because it put him face to face with Kimberly’s murdered angel. “I’d like that very much.”

9

VINCENT’S WARDROBE COULDN’T KEEP UP WITH THE sweat. It slicked his neck, rolled in beads down his face, and soaked the underside of his hair and a band where the borrowed hat rested on his head. His hands were still greasy from a lunch of some fried starchy fruit and tubers, served in a paper wrapper, and his wardrobe was too overwrought to deal with it.

He mopped his face on his sleeve, further stressing foglets already strained by the jostling crowd and the press of his escort on either side, and tried to regulate his breathing. The nausea was due to the heat, he thought, and not the food; his watch didn’t report any problems beyond mild dehydration and a slightly elevated body temperature, which he was keeping an eye on. It wasn’t dangerous yet, just uncomfortable, but Miss Pretoria was tireless. She tugged Vincent’s sleeve to direct his attention to a Dragon costume operated by two men, the one managing the front limbs walking on stilts and operating paired extensions from his wrists that simulated the beast’s enormous wings. “How could something that big fly?” he asked, checking his step to let the puppet shamble past.

“They must have been somewhat insubstantial for their size,” Miss Pretoria said. “The khir, which are the Dragons’ closest living relatives, have a honeycombed endoskeleton that leaves them much lighter than an equivalent terrestrial mammal. So the Dragons would have been about the same weight and wingspan as the largest pterosaurs. And we think they soared more than flew, and may have been highly adapted climbers.” She turned to watch the puppet proceed down the street, bowing and dancing, bells shimmering along the span of the wings.

Her eyes widened as she turned to him. “Miss Katherinessen, you should have said something.”

“I’m sorry?”

“I think we’d better get you out of the heat.” She turned to Shafaqat, gesturing her forward. “Would you call for a car, Miss Delhi? And get Miss Katherinessen something to drink? We’re going to find some shade.”

“I’m fine,” Vincent said, as Pretoria latched onto his wrist and tugged him toward a side street where the buildings would block most of the glaring light. “Nothing a cold shower and a glass of ice water wouldn’t cure.”

Pretoria clucked her tongue and bulldozed over him. “You’re not adapted to this climate, and I’m notexplaining to my mother why it is that a Coalition diplomat suffered heat exhaustion under my care, no matter how manly you need to prove you are.”

He checked over his shoulder. Shafaqat moved through the press of bodies efficiently, her height, bearing, and uniform gaining a certain deference even from costumed, staggering merrymakers. Vincent had never seen a crowd like this on a Coalition planet: jostling, singing, shouting, raucously shoulder to shoulder and yet decorously polite. He wondered if it was a side effect of living packed into their alien cities, encircled by the waiting jungle, or of their rigid social strictures and their armed obeisance to the code duello.

Pretoria’s hand cooled his skin as she pulled him into the shady side street, which wasn’t any less crowded than the square. She pulled his wrist out and up as he made the choice to let her touch him without resistance. It was foreign, invasive. His skin crawled and stung when she pulled back, steadying his hand with her other one, and bent over it.

“You’re burned,” she said. “Not too badly, I think, but it’s going to hurt by tonight.”

“That’s impossible. My wardrobe should filter UV–”

But his wardrobe was overstressed, and of course he’d had to dial it down to keep it from zapping pedestrians–or Miss Pretoria, with her frontier touchiness. She squeezed his wrist, and the cool pressure of her palm turned to shocking heat. He yelped and yanked his hand away.

“Sunburn,” she said. “Good thing you wore long sleeves.” And then she reached out and caught his shoulders, pushing him against the wall, and he would have shrugged her away but the blood roared in his ears and the orange status lights flickered in his watch. The street swam around him, aswarm with people who might have been staring at him curiously if he could have focused on their faces. “You know,” he said, uncertainly, “I don’t feel too well at all.”

Her hand closed on his wrist again, searing, as she tugged him into motion. Shafaqat reappeared on his other side. “Miss Pretoria?” Something icy and dripping touched his hand.

“Drink that, Vincent. Miss Delhi, did you call the car?”

“I’m fine,” Vincent insisted, even though he couldn’t quite lift his feet. He broke Pretoria’s grip, more roughly than he had intended, and ducked his head, blinking, as he tried to get a good look at the display on his watch. Nausea made him gulp. “I don’t think I should drink anything.”

They ignored him. “It’s on the way,” Shafaqat said. “Where are we going?”

“Redirect it to Pretoria house. We can get him there and into a cold shower by the time it could reach us and find a place to land in this crowd, and it’ll be a huge flap if we have to send him to the clinic.” Miss Pretoria cursed. “I’m an idiot. I thought he would tell me if it got to be too much.”

“Men,” Shafaqat said. Vincent could picture the twist of her mouth from her tone.

“Angelo would tell you it’s Vincent in particular, not men in general,” Vincent said.

“Vincent, can you walk a little way?” Pretoria said, concerned, carefully pronouncing his given name.

“I can walk.” He wove slightly, but steadied. “How far?”

Shafaqat answered, pressing the cold, sweating thing into his hand again. He closed fingers that didn’t want to tighten around the coolness of the globe. “Less than a kilometer. And you have to drink this.”

“I feel sick.”

“You feel sick because you’re dehydrated. You need fluids. If you can’t keep it down you’ll need an IV. Slowly, just a sip at a time. But drink.”

Her tone reminded him of Angelo’s. Not exactly hectoring, but assured. Somebody steadied his hand as he raised the globe to his mouth, found the straw, and sipped.

Once the fluid–something tart, with bubbles–flooded his mouth, it was an act of will not to gulp it all. Temperature shock chilled his teeth in the bone, replacing the dizzy headache with a stabbing one. He found his footing. “Better.”

Now that he’d become aware, the prickle of warmth across his shoulders and back and thighs took on new significance. He’d worn long sleeves, but if his wardrobe’s UV blocking had failed, those sleeves wouldn’t have protected him.

He was going to have one hell of a radiation burn.

“Drink more,” Pretoria reminded, keeping him on the shady side of the street. He obeyed, the sugary fluid a relief. He finished the globe quickly despite his attempts to regulate his intake. They’d stopped walking, pausing in a much smaller side street–more of a service access route, too narrow for a hovercar and tight even for ground transport–without the press of foot traffic. As Shafaqat pressed another globe into his hands–this one a little warmer, but also dripping condensation–Miss Pretoria turned aside and placed one hand on the wall of a nearby structure.

“House,” she said, “I need cold water, please, in a basin.”

He still felt unwell–disconnected–but it was his body, now, and not his mind. He sipped the second beverage, and asked, “Is this Pretoria house?”

“It’s the back wall of a marketplace,” Miss Pretoria said, and a cubbyhole appeared about a meter up the violet‑gray wall.

Shafaqat urged Vincent toward it. He went, finishing the second drink before relinquishing the spent globe into the security agent’s hands. She crushed it and made it vanish.

“Roll up your sleeves,” Miss Pretoria said. He didn’t bother; his wardrobe didn’t mind wet. He plunged arms webbed with distended veins in water as frigid as if it flowed from a cave. The cold first saturated his arms and ached in the depths of the bones, and then the slug of chilled blood struck his heart and spilled up his throat. He gasped and remembered to knock his hat off before sticking his face into the water.

When he straightened, water dripping down his forehead and under the collar of his shirt, he was suddenly clearheaded. He turned and slumped against the wall, tilting his head back to encourage the water to run from his braids down his neck and not into his eyes. He coughed water, blew it from his nostrils, and panted until the last of the dizziness faded. His wardrobe, out of the sun now and given half a chance to work, cooled him efficiently, evaporating sweat and water from his skin, drawing off excess heat.

“Thank you,” he said, when he dared open his eyes and try to focus. It worked surprisingly well. First he saw Shafaqat, and then, over her shoulder, he saw something less encouraging. Five women, sidearms drawn, faces covered by Carnival masks.

“Miss Pretoria?” He surreptitiously dialed his wardrobe up.

She turned, following his gaze, and stiffened with her hand hovering above her weapon.

“There’s only five of them,” Shafaqat said.

“Good odds,” Pretoria said. She sounded as if she meant it. Vincent pushed away from the wall and stepped up to cover her flank. If it were histarget, he’d have another team covering the side street. “Three more.”

“Thank you.” Pretoria’s right hand arched over her weapon, a gunslinger pose, fingers working. She’d unfastened the snap; Vincent hadn’t seen her do it.

Pretoria and Shafaqat shared a glance. Shafaqat nodded. “Run,” Pretoria said. Flat command, assumed obedience.

“I don’t know where I’m running to.”

“Pretoria household.” Miss Pretoria stepped diagonally, crowding him back.

“Lesa, there’s eight–”

Her grin over her shoulder was no more than a quick flash, but it silenced him. He looked again, saw the way the masked women paused to assess every shift of balance–Pretoria’s even more so than Shafaqat’s.

He recognized that fearful respect. Lesa Pretoria had a reputation. And for whatever reason, they didn’t want to kill her. He acquiesced, though she probably couldn’t see him nod. “How do I get there?”

“Follow the ghosts,” Pretoria snapped, as the first group of adversaries picked closer, fanning out. If Vincent were in Pretoria’s shoes, he’d wait until they were close enough to get in each other’s way. If he were gambling that they didn’t want to kill him.

“Ask House,” Shafaqat clarified. Slightly more useful. She stood with one shoulder to the street, narrowing her profile, her hand also hovering over her holster. “We’ll delay them. Go left”–through the line of three, rather than the line of five–“Go on. Go.”

Vincent went.

Angelo might looklike the dangerous one, but that didn’t mean that Vincent had no idea how to take care of himself in a fight. He charged, zigzagging, and trusted his wardrobe to soak up any fire he didn’t dodge.

When the fire came, it wasn’t bullets. A tangler hissed at his head, but his timing was good, and his wardrobe caught it at the right angle and shunted it aside. Gelatinous tendrils curled toward him, and sparks scattered where they encountered the wardrobe and were shocked off. Two of the masked women grabbed for him as he sidestepped the tangler, and his wardrobe zapped their hands. He shoved past them as shot from a chemical weapon pattered behind him, spreading the sharp reek of gunpowder, while he twisted against grabbing hands.

Firearms echoed again, and one of the women who was clinging to his arm despite the wardrobe’s defenses jerked and fell away. Vincent shouldered the other one aside and ran.

Leaving a couple of women to do his fighting for him. But they were security, and they had ordered him to clear the area.

If it had been Michelangelo, he would have done the same.

Once he reached the crowded street, he could no longer hear the footsteps behind him. He wove between clusters of merrymakers, half expecting some good Samaritan to trip him as a purse‑snatcher or runaway, but it was Carnival, and other than a few turned heads, bright laughter, and a startled exclamation–no one paid him heed.

He couldn’t run for long. His head started spinning again, and he’d left his hat lying in the damp dust. He let himself drop into a jog, then a walk, sidestepping drunks and Dragon dancers and wandering musicians. The toe of his shoe dragged on the pavement and he stumbled, his wet hair steaming. But Miss Pretoria had also told him that her household was close, and Shafaqat had told him how to get there.

He ducked down a side street strung with more cut flowers, past three men and five women carrying shopping bags, and stepped into the shade. “House,” he said, feeling ridiculous, although he’d waited until there was a gap in the flow of people, “show me how to get to Pretoria household.”

At first there was no reaction. But then a shimmer formed along the wall, neither an arrow nor a trace, but something like a ripple on water. It was a pale sheen of blue luminescence, dim in shadow and brighter in sunlight, and it led him further along the street he had ducked down.

It didn’t take him long to realize that he wasn’t being led by the most direct route. Instead, House brought him down side streets, less populated ways, and through shadowing courtyards. It concerned him, but he didn’t know which other way to go, and so he followed. The shimmer ran along walls, or sometimes immediately underfoot, always a half‑step ahead until it brought him back into sunlight on a quiet byway with only a little pedestrian traffic, not broad enough for a car. There, at the bottom of a set of broad shallow steps leading to a screened veranda, it abandoned him, vanishing into the pavement like oil dispersing on water.

He looked up the steps at the front door, which glided open. Behind it stood a young woman with Lesa’s broad cheeks but a darker complexion and curlier hair. “House said to expect you,” she said. “I’m Katya Pretoria. Come in off the street.”

That’s a bit more than a goddamned giant utility fog,Vincent thought, but he didn’t hesitate to climb the steps.

“Your mother might need help,” he said, pausing to glance over his shoulder, back in the direction from which he’d come.

“Household security’s on the way.”

10

“MISS KUSANAGI‑JONES,” MISS OUAGADOUGOU SAID AFTER he had entirely managed to lose track of the time after, “do you need to check in with your ship?”

He glanced up from sketching schematics on his watch, refocusing on Miss Ouagadougou through shimmering green lines that overlaid the physical gallery. His watch identified her as an individual rather than a part of the landscape, and backgrounded the display plan behind her. It looked odd, sandwiched between her and a Gerуnima Cruz Montoya casein‑on‑paper painting. “Sorry?”

“It’s past teatime. And the station should be overhead in a few ticks. We’ll eat upstairs, and I thought you might–”

“Very kind,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, recollecting himself. “Does this suit?”

“The schematics?” Her hair bobbed on the nape of her neck. “If you finalize them, I’ll upload them to the ministry net, and they’ll keep a crew in tonight to finish the setup. It actually works out better this way.”

“It?” He was already sealing the plans, satisfied with the exhibit. Miss Ouagadougou had a good eye. “Lead on,” he said, before she finished fussing with her headset.

They ascended the lift in companionable silence, Miss Ouagadougou still fiddling and Kusanagi‑Jones pulling up a sat‑phone license on his wardrobe menu. He’d need a relay station; his watch couldn’t power orbital communication.

If he was lucky, his communication would reach Kaiwo Marubefore she dispatched a packet‑bot back to Earth to swap mail. It would still take six months to send a message and get an answer, assuming The Pride of Ithacaor one of the other inbound ships was close enough to relay the bot’s signal. But at least this way the message would be in the queue.

If anything happened.

He coded two reports. The first used a standard diplomatic cipher, and detailed a strictly factual, strictly accurate report of his and Vincent’s doings since landfall. The second, concealed in the first and still largely innocuous to Coalition eyes, concerned itself with a perceived obstructionist element in New Amazonian government.

There was a third message, contained not in a discrete data stream, but in the interplay of the others. In the cracks between. Kusanagi‑Jones concealed an ironic smile.

This one, of necessity brief, must be sent when Vincent wasn’t present to record it. It was sealed eyes‑only, quantum coded. When Kusanagi‑Jones broke the seal on his own end of the code, a quantum entanglement triggered a wave‑state collapse on the other end of the system, alerting his principal that a message was en route. The only man in the universe who could read the message was the one who held the other half of the key.

That man was Siddhartha Deucalion Hunyadi Lawson‑Hrothgar. He was a senior member of the Earth Coalition Cabinet. And its contents, if they couldhave fallen into the wrong hands, would have meant surplusing and execution not only for Kusanagi‑Jones, but for Lawson‑Hrothgar as well.

Kusanagi‑Jones understood Vincent’s position. The great‑grandson of a Colonial Founder, the son of Captain Lexasdaughter–the most powerful head of state remaining under Coalition control–Vincent would work withinthe system, attempt to ease the Coalition’s stranglehold through diplomatic means.

Kusanagi‑Jones, with the assistance of a revolutionary patron, had chosen another path.

Which was the thing Vincent could never be permitted to learn about New Earth, and the destruction of the starship named Skidbladnir,and why they had been separated: that it had happened so because Michelangelo had planned it that way.

“When you report,” Miss Ouagadougou said, as they stepped out into brilliant sunlight, “I’ll have something to add.”

Kusanagi‑Jones wouldn’t show startlement. Instead, he stepped aside to give her a line of travel and fell into step behind. “Something about the plan I’d like to discuss. May I uplink the new version to your datacart?”

“Of course.” She pulled it out of her hip pack and flipped up the cover. “Password?”

He gave her one, and established a single‑photon connection. The security detail hung back, just out of earshot if they spoke in level tones. New Amazonian courtesy. But there were some things you didn’t say out loud.

Green letters flashed across his vision and vanished. The director of security is a radical,Miss Ouagadougou said. Get her to enlist.

Kyoto?he asked. That old dragon?

She’s inclined pro‑Coalition. A free‑maler. Claude’s a loss. Saide Austin holds her purse strings, and Saide Austin…He glanced at her as the text scroll hesitated. She shrugged, a slow rise of her shoulders, a quick tilt of her head. He recognized the name from the gallery. Saide Austin.

More than an artist, apparently. You’re a Coalition agent.

Since before the war.

He wondered what they’d given her to buy her loyalty–money, access to Coalition art treasures–or if hers was an ideological treachery.

She put her hand on his arm. I’ve imbedded an information packet in your copy of the plan. She transmitted a code key, which he saved. “I’m starving,” she said. “It’s been hours since lunch.”

“Miss Ouagadougou?”

Kusanagi‑Jones looked up. One of the agents had stepped forward. He might as well have been a shadow on the wall.

“Cathay.” Miss Ouagadougou smiled. “Problem?”

“Miss Pretoria requests you and Miss Kusanagi‑Jones join her at Pretoria house.” Cathay–Kusanagi‑Jones was uncertain if it was her first name or last–smiled. “A car is waiting.”

Miss Ouagadougou wet her lips, and Kusanagi‑Jones’s pulse accelerated. Problem.

“My uplink,” he said. He’d been hoping, frankly, to get another look around the galleries and see if he could find whatever passed for a power conduit. Wherever they had the power plant hidden, there had to be wiring. Electricity didn’t transmit itself, and he’d seen no signs of microwave receivers. Room temperature superconductors, he’d guess.

“Do it in the car,” she said, fingers closing on his wrist.

Problem. Yes, indeed.

Kii touches the cold illation machines that populateKaiwo Maru ’s core. They are intelligent, in their own way, but Kii is not of interest to them. They process Kii, and ignore.

Kii contemplates, and the Consent observes. There is no determination yet, as Kii analyzes the Governors’ decision trees. The Governors are aware. They are adaptive. They are goal driven, and they are improvisational.

But their entire purpose, Kii soon understands, is the maintenance of the encroaching bipeds. They are a predator. A constructed predator, a coolly designed one. They exist to assure the bipeds do not overburden their habitat. They are ruthless and implacable, and their disregard for Kii is not founded on a lack of intelligence or awareness. Rather, Kii is external to their parameters. Their only interest is the bipeds. They are created creatures, as Kii is a created creature, a program contained in a virtual shell. But unlike Kii, they are not alive.

They are notesthelich . They are not alive. In this fragment, Consent is reached with ease.

Vincent shouldn’t have been so relieved that it was Robert who took charge of him once they were inside. It was unprofessional. But for all his size, scars, and shaven head, the big man was a calming presence, revealing no threat‑registers. It was the easy kind of personality that deservedly confident, competent, unthreatened people projected, and Vincent really was not feeling well at all. He let Robert bring him into the cool depths of the house, under more of those swags of dead flowers, and show him into the fresher. Or…make one for him. Now that he was watching for it, he could see how it worked, the way the building anticipated and fulfilled requests. A limited teachable AI, at least, if not sentient.

The city was not so much haunted as programmed.

“Take off your shirt,” Robert said as the door irised shut behind them. He reached to grab cloth, and Vincent, who hadn’t dialed his wardrobe down, stepped back fast and tilted his chin up to look Robert in the eye. White teeth shone in contrast to Robert’s plum‑colored lips, and Vincent sighed.

“No,” Robert said. “That’s not a proposition.”

Vincent knew. There was no erotic interest at all, either predatory or friendly. “It doesn’t work like that.”

Robert backed off, and Vincent touched his wrist and made his wardrobe vanish, dialing down the protection, too. He turned, showing Robert his back, and bit his lip not to shiver away when Robert reached out, slowly, making sure Vincent could see him in the mirror as he paused his hand a centimeter from Vincent’s shoulder blade. The heat of his palm made Vincent flinch; when Robert drew his hand back, he scrubbed it against his vest as if to rub the radiant warmth away. “That’s going to blister. Have you ever had a sunburn?”

“No,” Vincent said.

“You’ll feel nauseated, achy, tired. You’ll experience chills. House, some burn cream, please? Miss Katherinessen, into the shower. Cold water will help. Essentially, you’re experiencing a mild radiation burn.”

“I’ve had those,” Vincent said. His watch would handle the worst of it: he could manage his chemistry to alleviate the flulike symptoms, and his licenses included both powerful painkillers and topical analgesics.

Another aperture expanded before him, leading him into a smaller chamber. He ducked through, stepping over the ridge while it was still opening, and sniffed hard. The pull of raw skin across his back and thighs was an unsubtle reminder toward caution. He paused a moment, giving his wardrobe enough time to collect its foglets so they wouldn’t wash away. There were no controls in the stall and no obvious showerhead.

“House,” he said, experimentally, as the aperture closed between him and Robert. “Cool water, please.”

It pattered on his head like rain.

Once Miss Ouagadougou had ascertained that Vincent was well, Kusanagi‑Jones breathed a sigh of relief and set about working out how to adapt his watch to the car’s hub. He’d have to piggyback on its signal, which meant all the more opportunities for the transmission to be intercepted, but it wasn’t as if there were a secure channel on the entire damned planet. You closed your eyes and put your trust in cryptography.

He sent the message with Miss Ouagadougou’s addendum, unlinked, and sat back against the upholstery. Cloth rather than leather. He permitted himself to sag into it. “What happened?”

In spare details, Cathay told him. “Miss Pretoria?” he interrupted, when she paused to draw a breath.

“Fine,” she said. “Uninjured. She has arranged to meet us at Pretoria house. You and Miss Katherinessen are asked to limit your movements until we sort out which faction is responsible for the kidnapping attempt.”

“Of course.” And of course, the attempt itself could be nothing more than a smokescreen to justify tightening the leash. But that was Vincent’s department, not his.

He was still going to shave thin strips off Vincent.

The car ride was brief. It still amused Kusanagi‑Jones that the automobile had to be putsomewhere when they arrived rather than vanishing in a blur of fogs. It was, in point of fact, too large to fit down the narrow alley that led to Pretoria house, and he and Miss Ouagadougou and Cathay disembarked at the bottom of the street so the driver could take it away. Cathay, he noticed, stuck as close to his side as he would have stuck to Vincent’s, shielding him with her body.

He’d expected Lesa Pretoria. The young woman who waited at the top of the stairs looked tolerably like her, but younger and softer around the eyes. “Katya Pretoria,” she said, beckoning. She didn’t step out into the sun, and Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t blame her. The brief walk from car to porch was enough to make his skin sting. “It’s a pleasure to meet you, Miss Kusanagi‑Jones. Your partner’s being seen to–”

“Vincent wasn’t injured?”

“He just got a little too much sun,” she assured, extending her hand. Kusanagi‑Jones brushed his wrist to dial his wardrobe down and accepted the handshake as he crested the stairs. She pulled him up the last step easily. He wasn’t tall, but he weighed more than he seemed to and probably had twenty kilograms on her. She braced to take the weight, but didn’t grunt. “You can speak with him as soon as he’s out of the shower.”

“Sorry to be so early to dinner.”

Her smile broadened, unmistakably flirtatious. Miss Ouagadougou cleared her throat from the bottom of the steps, but Katya ignored it. “It’s good to have fluid plans, don’t you think? Miss Ouagadougou, thank you for a safe delivery. We’ll have him home in time for the ceremony tomorrow, I promise.”

And before the historian could quite answer, Katya took Kusanagi‑Jones’s wrist and drew him into the house, security following. As soon as they were inside, though, Kusanagi‑Jones stepped away from her to get a sense of the space. The house was cool inside, shadowed by the broad verandas and rich with breezes. “How much seeing to did Vincent require?”

“Miss Katherinessen has made himself quite at home,” she said, and the grin turned into a wink. “One of the senior males is seeing to him. He’s in good hands.”

Kusanagi‑Jones snorted. He let a little jealousy show. It couldn’t hurt, and it was easy enough to feel jealous of Vincent. He had a way of getting what he wanted, after all. “The question is, is your male safe at Vincent’s hands?”

“Robert’s my sire,” she said. “He’s safe most places. He’s a three‑time Trial champion, all city, and before he retired he was third overall.”

A gleam of pride reflected through her voice. He wasn’t likely to forget the Trials quickly. And he remembered Robert from the docks, and Robert had had scars. And had been beautiful and dark.

Just to Vincent’s taste.

But interesting, that pride. My sire. A young woman proud of her father, even here. He supposed just because you kept someone as chattel, it didn’t mean you didn’t care for him. Especially if you thought it was for his own good. “Well, I hope he’s not driven to defend his honor at Vincent’s expense,” he joked, waiting for her response.

Which was a chuckle. “Don’t you envy him that? That sense of…entitlement?”

She’d picked that up on a moment’s acquaintance, had she? Kusanagi‑Jones snorted hard enough that it stung. “Envy Vincent? Not the entitlement. Sometimes maybe the privilege that produced it. Trying to drive a wedge between us, Miss Pretoria?”

“Of course not,” she said, maintaining a perfect deadpan. “That’s what they hired my mother for.”

11

AFTER THE SHOWER, VINCENT LET ROBERT SMEAR HIS BACK with a gelatinous yellow substance that stung and soothed, and smelled of cucumbers and mint. He could have pulled up a license, but there was no reason to give away more of the capabilities of his wardrobe than he needed to. Robert worked steadily and quickly, and when he was done and Vincent summoned a new outfit from his wardrobe, he made sure he programmed it not to absorb the gel. It slid and stuck, but it did help. He turned back and offered his hand to Robert for yet another of the endless New Amazonian handshakes. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome,” Robert answered. His clasp was firm.

Vincent was unsurprised to feel the edged corners of a chip pressed into his palm as he dropped his hand, and he cupped his fingers slightly to hold it. The outfit he’d chosen had pockets suitable for the nonchalant shoving of hands, so he did.