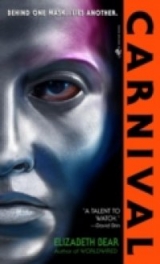

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

By the time he dared to lift his head and let her lift hers, they had. Elder Singapore shoved him away violently and sat. “You’ll hear about that,” she snapped.

He permitted it only because they were behind a screen of security agents, and–to be honest–he wanted to get to Vincent, who was making much less fuss about an equally rough takedown.

Two bullets hung beside Kusanagi‑Jones, trapped in the aura of his wardrobe like hovering bees. He dialed a glove and plucked them out of the fog.

Shafaqat already had a transparent baggie ready, and she took the bullets–pristine, despite having been stopped by the antishock features of the wardrobe fog–and made them vanish without so much as catching Kusanagi‑Jones’s eye. He could get to like that woman.

“Vincent.” He crouched as Vincent pushed to his knees.

“Unharmed,” Vincent answered, despite the evidence of a scratch across his cheek and a bloody nose. “Good work.”

Kusanagi‑Jones smiled in spite of himself, standing. People in the square were shouting, shoving. Something shattered against the stage, and Vincent ducked reflexively. “All I did was yell. Local security swarmed the shooters. Let’s get you off the stage, Vincent. They’re not pleased about the security–”

“Hell, no,” Vincent answered, wincing again–this time, Kusanagi‑Jones thought, from the pain of moving in his own stiff, burned skin. His hand, fever‑warm, slid into Kusanagi‑Jones’s, and he levered himself up. “I have a speech to give.”

Kusanagi‑Jones, watching Vincent shove ineffectually at his braids and mop blood onto his hand as something else was hurled and broke, bit his own lip hard to stop his eyes from stinging.

Because now he knew what he was going to do.

15

IT WAS FORTUNATE THAT VINCENT HAD PRACTICED HIS speech until it was as automatic to his recall as his system number, because later, he couldn’t remember having recited a word of it. He knew he extemporized the introduction, and if it hadn’t been recorded he never would have known what he said. He must have made quite an impression with the blood caking his face and the split lip, clinging to the edges of the lectern like a drunk in an effort to keep the weight off his knee. His wardrobe provided a brace, but that hadn’t helped absorb the impact when he went down.

At first, the crowd had been restive, muttering, rustling like a colony of insects with passed whispers. More security agents arrived while Vincent was speaking, filtering through the audience, but they didn’t reassure him as much as Michelangelo’s silent warmth at his elbow. Or the way the crowd calmed as he spoke, subsiding like whitecaps after a passing storm.

When he stepped back from the lectern, he had silence. A long moment of it, respectful, considering. And then first snapping, scattered as the first kernels of corn popping, and then stamping feet and shouts–some approval, some approbation, he thought, but nothing else shattered on the stage.

He waved and nodded. Lesa was on his right side, also waving, and her left hand threaded through his arm as she tugged him back. Michelangelo was right there, too, covering Vincent with his body, as Saide Austin stepped forward.

“Like to see her match that,” Angelo murmured.

“I did okay?”

Angelo touched him carelessly. “Real good.”

“Good,” Vincent said, aware that he sounded petulant, and not caring. He was seeing stars now–literally, sparkles in front of his eyes–as the adrenaline wore off. “My nose hurts.”

“And your back?” Lesa asked.

“My back,” he said, with tight dignity, “hurts more.”

Vincent looked gray, the blood draining from his face as he sat stiffly upright on the chair, his leg stretched out before him to ease the knee. Kusanagi‑Jones slipped his hand across the gap between chairs and took Vincent’s, squeezing, hiding the action with their bodies. Vincent sighed and softened a little, his shoulders falling away from his neck, though he had the sense not to lean back. Shafaqat handed Vincent a wet towel while Elder Austin was still talking. He took it right‑handed, and didn’t release Kusanagi‑Jones’s hand with his left while he dabbed at the crusted blood on his lip. “At least my nose isn’t broken.”

Kusanagi‑Jones widened his eyes and spoke in an undertone. “It’s supposed to look like that?”

“The Christ, don’t make me laugh.” He winced, and then flinched, as if the act of wincing hurt.

Vincent handed the bloody cloth back to Shafaqat and glanced at his watch, and Kusanagi‑Jones knew he was thinking about upping his chemistry and dismissing the idea. He was still idly checking readouts when Austin’s speech came to an end, a study in deceptive inattention, but when he glanced up, his eyes were sparkling. They stood when everybody else did, herded by security agents, and filed down the steps and through the crowd again. Kusanagi‑Jones covered Vincent as much as possible, varying distance and pace within the crowd, and for the first time was actively angry that all of the New Amazonian security was female and that Vincent was taller than any of them and all the New Amazonian dignitaries. And, of course, taller than Kusanagi‑Jones. There was nothing to block a head shot, if there was another shooter somewhere in the crowd.

Which meant relying on the agents assigned to crowd coverage and Vincent’s wardrobe to get them through safely. And Kusanagi‑Jones thought that just possibly, he would rather have severed his own fingers with a pair of tin snips than made that endless, light‑drenched walk. Though the crowd was calm, respectful, their attention oppressed Kusanagi‑Jones like the weight of meters of water, cramping his breathing.

He managed a free breath when they stepped out of the square and into the cool shade of the gallery lobby. A brief bottleneck ensued as politicians pulled off shoes and hung them on the racks, but it wasn’t as bad as it could have been. Only the dignitaries, security, chosen observers, and a small herd of media would travel past this point.

When he looked up, Kusanagi‑Jones found himself on the periphery of a glance exchanged between Elder Kyoto and Vincent that Kusanagi‑Jones would have needed all of Vincent’s skill to interpret. Lesa caught it, too, and by her frown she understood it far better than Kusanagi‑Jones–but she said nothing.

Now that he had a plan, the wait was nauseating. He knew how Vincent, having formulated his strategy, would be behaving in Kusanagi‑Jones’s shoes. He would already have assessed the possible ways in which the subject might react, and he’d have a contingency for each. He’d have alternates mapped and a decision tree in place to deal with them, with counterplans in the event of failure or unexpected consequences.

Kusanagi‑Jones had only one idea, and it involved doing something he hadn’t willingly done in his adult life. And he was basing it not on facts, probabilities, and meticulously calculated options, but on three entirely illogical factors.

The first of these was Kii. Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t know what to do about the Dragon’s ultimatum. He was as torn as Hamlet; Kusanagi‑Jones did not, in all impartiality, consider himself capable of making the demanded choice. He wasn’t a decision maker. He would do anything possible to avoid being placed in that position of responsibility.

It was a strength in some ways. One of the things that made him an accomplished Advocate was his ability to argue both sides of a predicament to exhaustion. But he’d been able to rely first on Vincent to make the tough calls, and then, after Vincent, on the fact that he was limited by scandal to unimportant missions to prevent it from becoming a weakness. It was Vincent’s job to decide, and Kusanagi‑Jones’s job to back Vincent up.

Except when he was betraying him over politics, but that, while ironic, was orthogonal to the argument.

The second factor was Vincent himself. Kusanagi‑Jones couldn’t face stepping away from him again. He’d done it once, ignorant of the cost, as the price of something he had thought more important than either of them. He stillthought it was more important. But he wasn’t sure he would live through it twice.

And yes, it would mean his life if Vincent reported him. He had no illusions. Except, perhaps, for the illusion that Vincent wouldn’t do it. Vincent’s loyalty to the job had always been unimpeachable…but Kusanagi‑Jones was about to gamble that his loyalty to the partnership would outweigh it.

In the final analysis–to dignify his gut belief with an entirely unjustified word–he didn’t believe Vincent would kill him. Which led to the third factor. Which was what Vincent had said to him in bed, regarding Skidbladnir,that had flexed Kusanagi‑Jones’s shoulders and neck in a shivering paroxysm. But it was possible–just–that Vincent had done it on purpose, had chosen his moment and found a way of letting Kusanagi‑Jones know he suspected, without allowing it to become an accusation or an admission of retroactive complicity. More, it was possible that Vincent was letting him know that Vincent was about something equally dodgy himself, and wanted his help. It was a daydream. Denial. Fantasy that didn’t want to deal with the reality of how compromised he truly was. But like pearls seeded in oysters, great treasons from small irritations grow.

He couldn’t mount a better option. Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones, Liar, was going to have to tell someone the truth. And now that he’d decided, the wait was killing him.

As they broke into groups for the lifts, Kusanagi‑Jones caught Vincent’s eye and gave him the subtlest of smiles, nothing more than a crinkle of the corners of his eyes. Vincent returned it, careful of his bruises, and Kusanagi‑Jones swallowed a forlorn sigh.

It was going to be a long, long day.

He repeated those words like a silent mantra all through Elder Singapore’s and Elder Austin’s second round of speeches, these taking place against the unpolished back of the black granite panel that blocked the view of the rest of the display from casual eyes, and continued it as Vincent stepped up to the focal point. He didn’t need his mind engaged to run security. After fifty years, his reflexes and trained awareness did a better job of it if he kept his consciousness out of the way.

His thoughts still chased an endless, anxiety‑producing spiral when Vincent joined Elder Austin and Miss Ouagadougou to lead the group around to the polished, graven side of the wall. Kusanagi‑Jones insinuated himself at Vincent’s side, and so he was one of the first around the corner to observe–

–an empty space in the middle of the gallery floor.

Phoenix Abased,all four and a half metric tons of her, was gone.

What followed was more or less predictable. Elder Kyoto took charge of the scene, and Vincent found Lesa hustling himself and Michelangelo to a car, passing through a crowd of insistent media with very little pause for politeness. For a moment, Vincent thought one of them might reach for her weapon, but Lesa fixed the woman with a calm, humorless stare that seemed to persuade her of the better part of valor, and then slid into the backseat opposite Vincent and Angelo.

The door sealed and Lesa slumped. “Miss Katherinessen. You certainly know how to keep a party interesting.”

“Surely you don’t think I–” Vincent fell silent at the wave of her hand. A few minutes passed, silence interrupted only by the blaring of the groundcar’s horn as it edged through streets jammed with Carnival revelers.

“You haven’t the means,” she said. “It had to be somebody with override priority on House.”

“Override?…”

Her eyebrow rose. He fell silent. Sticky leather trapped the heat of his burned skin against his body, and he shifted uncomfortably. Angelo’s regard pressed the side of his face like a hand. Angelo, of course, had been in that gallery until nearly dawn. But he hadn’t said he’d seen anybody, in particular near Phoenix Abased,and Vincent hoped he wasn’t thinking that Vincent was likely to hold him accountable for the theft.

“Override priority?” he asked again.

Lesa looked up from the cuticle she was worrying with her opposite nail. “House has three modes. It automatically adapts to any regular use to which it’s put. This is how most of the architecture develops. It will also do small things–forming a fresher in an unused space or rearranging the furniture–for anybody who spends a fair amount of time in a particular spot, and provide other favors such as directions or a drinking fountain”–she tilted her head at Vincent–“for anyone, anywhere.”

“And stealing a three‑meter statue from a public venue?”

“There’s the problem,” she said. “We didn’t build House. We just adapted it, learned how to program it.”

“And adapted to it. You’re saying there’s no security feed from the gallery?”

“I’m saying that anybody who could take that statue out could tell House not to remember. We’ll check the records–”

“Of course.” He managed it without a glance at Angelo. He’d been cloaked when he entered. The chances he could be detected were slim. “Please do. That means it’s somebody with clout.”

“Somebody in Parliament, if it wasn’t a ranking gallery administrator,” Lesa corrected after a reluctant pause. “We don’t let just anybody engage in urban renewal.”

“This isn’t the way back to the residence unless we’re going the long way,” Kusanagi‑Jones said a little while later.

“No,” Lesa said. “I’m bringing you to Pretoria house. I know who has access to the priorities there.”

“And security?”

They’d left the agents behind. Lesa seemed to understand the nuances of his question. “Shafaqat and Cathay are running a decoy operation,” she said. “Asha will follow us. Pretoria house has its own security, of course–”

“Of course,” Vincent interrupted, ever so dry. “And there’s no evidence that itcould be compromised.”

“Not by a male,” Lesa said.

Kusanagi‑Jones raised an eyebrow at Vincent, who rolled his eyes. “Angelo is probably finding your remark somewhat cryptic.”

“One of our household males has taken advantage of the recent confusion to run away,” Lesa said. “We are trying to recover him before it becomes public knowledge and we have to make an example of him when we catch him. Thank you very much for airing our dirty laundry, Miss Katherinessen.”

“Anything you can tell me, Angelo can hear,” Vincent said, which earned him another arch look from the Penthesilean. There was a subtext there that Kusanagi‑Jones wasn’t catching, and for a moment, he understood what it must be like for others, on the outside of his rapport with Vincent.

“The male,” Kusanagi‑Jones hazarded, his hands folded between his knees. “Robert, was it?”

Lesa, looking out the window, nodded.

Kusanagi‑Jones frowned. “Your secret is safe with me.”

He half expected to be installed in the harem, or whatever they called it, but he and Vincent were given a small, comfortable room with a balcony that opened onto Pretoria house’s inner court and left alone to compose or, Kusanagi‑Jones thought, incriminate themselves.

A young male servant who was familiar from the previous night’s dinner brought them warm sandwiches of scrambled, spiced vegetable protein and mixed greens, the bread made from some unfamiliar grain, and bottles–not bubbles–of a carbonated drink with a pleasing bitter aftertaste reminiscent of chocolate. They sat cross‑legged on the bed, the tray balanced on the covers between them, and picked at the food.

Neither one of them was hungry, but they were both determined to eat, which made the meal an extended comedy of dragging silences and lengthy chewing, interrupted by occasional distant cracks of thunder and the sound of music and shouting drifting from nearby streets. Nothing as minor as the attempted assassination of a head of state would put a cramp in Carnival.

Kusanagi‑Jones finished first and waited while Vincent picked bits out of his sandwich and poured drink into his glass one mouthful at a time. He waited poorly, bending his fingernails against the edge of the tray and wishing Vincent would break the silence with a conversational offer.

But Vincent seemed preoccupied, withdrawn. “All right?” Kusanagi‑Jones said finally, and then bit the inside of his cheek in frustration.

“Yes,” Vincent said, prodding his nose delicately with the tip of his finger. “Sore, exhausted, and full of released toxins, but I’ve been worse. Something’s preying on you.”

And if he was presenting strongly enough that Vincent could tell, Kusanagi‑Jones was doing even worse than he’d thought.

“Need to talk,” he said. And then, unable to bear the close intimacy of the two of them leaning together over their food, he swung his legs off the low New Amazonian bed and levered himself to his feet. The carpetplant dimpled under his soles. He strolled to the archway leading to the balcony and paused inside the air curtain, currents stirring the fine hairs on his arms.

The first fat drops of a tropical downpour splashed the green‑blue translucence of the balcony as the ceiling inside paled to simulate the storming sky. As the light outside dimmed, that within seemed to brighten in comparison, so when Kusanagi‑Jones glanced over his shoulder he was caught by the luster of rust‑colored highlights on Vincent’s hair.

He looked down, folded his arms to hide the way his hands were shaking–again–and stepped through the air curtain and out into the rain as if stepping through a spun glass drapery.

His wardrobe shunted it away, creating a shimmering outline centimeters from his skin. He pulled his folded arms apart and ran fingertips over his watch, opening the utility fog.

The water was warm. Blood‑warm, warmer than his skin, corpulent drops hitting hard enough to sting. He closed his eyes and tilted his face back, letting the rain wash him. It passed through his wardrobe without dampening the simulated cloth or affecting the hang of the outfit, soaking him, sluicing down his chest and thighs, saturating his hair.

He heard Vincent’s footsteps and saw his shadow cross the fisheye before Vincent spoke. “Do you suppose it’s safe?”

“Safer than the sunlight.”

“There could be pollution. Parasites.”

“Could be,” Kusanagi‑Jones said. Even when he dropped his chin to speak, water splashed into his mouth. It tasted strange, not neutral but crackling with ozone, faintly salty, sweet. From below, Kusanagi‑Jones heard voices, a woman’s and those of children, and the slap of bare footsteps running on wet pavement. He turned his right hand up to let the rain wash across the sealed nick on his palm. “Don’t seem too worried.”

Water pattered on Vincent’s hair and shoulders as he came outside. He paused at Kusanagi‑Jones’s shoulder, and Kusanagi‑Jones leaned back slightly, so their wardrobes meshed. The coded channel was carried on a single‑photon beam–an unimpeachable transmission. But it didn’t hurt to shorten the hop. “Vincent–”

Vincent’s hand on his shoulder almost made him jump out of his wardrobe. “If you’re about to tell me that you’re seizing command of the mission, Angelo, I don’t blame you. But I will put up a fight. Can’t we come to an accommodation?”

Kusanagi‑Jones stopped hard, with his jaw hanging open. He put one hand out, found the balustrade, and used it to pivot himself where he stood. “Beg pardon?”

To see Vincent staring at him, similarly gape‑mouthed and blinking rapidly against the rain that dripped from his lashes. “I thought–” He stepped away, let his hand fall, and tilted his head back. “The Christ. I thought you’d made me.”

“As a double,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, understanding, but needing the confirmation.

Vincent snorted, shaking his head, water scattering from short, randomly pointed braids. He rocked back and slumped against the wall beside the doorway. “Well, now you know. It’s a good thing Idon’t claim to be a Liar.”

“Who?”

“You know I can’t tell you that–”

“Vincent. I won’t hand you over. Or your connections.”

“I still can’t tell you.”

“What organization?”

The smile was tight, Vincent’s hands curled into fists beside his thighs. He didn’t look down. Kusanagi‑Jones hadn’t thought he would. “One that doesn’t have a name.”

Kusanagi‑Jones shouldn’t have been riding a rush of relief and joy; emotion made you stupid. But it welled up anyway. He reached out and took Vincent’s arm, the dry wardrobe sliding over wet skin beneath. “Know what I’m thinking?”

“Do I ever? It’s part of your charm–”

Michelangelo took a breath and let the words go with it when he let it out. “I threw the mission on New Earth.”

“The Skidbladnirsuffered a core excursion,” Vincent said. “You couldn’t have had…” And then his voice trailed off. He tugged away from Kusanagi‑Jones’s hand, but not hard, and Kusanagi‑Jones held on to him. “Angelo.”

“I’m Free Earth,” he said. “Have been for decades. I killed Skidbladnir,Vincent, and everybody on her.”

“To keep New Earth out of the Coalition.”

“To give them a fighting chance.”

Vincent licked his lips and looked down, jaw working. Kusanagi‑Jones imagined he was toting up the dead–the ship’s crew, marines, civilians. He started to pull his hand back and Vincent caught it, squeezed, held. “Do you mean to do it again?”

“Here?”

“Yes.”

“If I have to.”

“Good,” Vincent said. “Me, too. We need a plan.”

If there was any tap on the door to the hall, neither one of them heard it over the sound of the rain, but Kusanagi‑Jones could hardly have missed it irising open. He pressed Vincent’s arm before stepping around him, turning him. Then he walked under the dripping door frame before pausing to shake the water off his hair. A shower of droplets bent the leaves of the carpetplant until his wardrobe took care of the rest, wicking moisture away so his clothes seemed to steam. “Come in,” he said to the young woman who waited outside in simple off‑white clothing with a Pretoria household badge embroidered on the breast.

She carried a slip of some sort in her hand, and was on the hesitant cusp of offering it to Vincent, who came through the door a moment after Kusanagi‑Jones and held out his hand, when she glanced at Kusanagi‑Jones for permission. Odd,he thought, and nodded, but not before he said “Wardrobe,” to Vincent.

He didn’t want him actually touchingthat thing.

The faint sparkle around Vincent’s fingertips when they touched the slip said Vincent had anticipated him. “Thank you,” Vincent said to the young woman. She nodded and stepped back, the door spiraling shut before her. Vincent glanced down, the slip dimpling lightly between fingers that didn’t quite contact its surface. “It’s for you.”

“Who from?”

“It doesn’t say.” Vincent generated a thin blade and slid it into the slip, along a seam Kusanagi‑Jones couldn’t see. A slight tearing sound followed, and then he tapped and inverted it, sliding out a second, matching slip. Vincent turned it in his hand and frowned at the black, ornate lettering.

“Another party invitation?” Kusanagi‑Jones asked, letting his mouth twist around the words.

“No,” Vincent said, raising a thin sheet of old‑fashioned card stock, wood pulp unless Kusanagi‑Jones missed his guess. “You seem to have been challenged to a duel.”

16

KATHERINESSEN APPEARED AT LESA’S DOOR IN THE COMPANY of Agnes, who had been working in a study near the on‑loan bedroom, and wordlessly presented her with a challenge card inscribed in Claude Singapore’s writing. Once she read it, he told her, minimally, that Kusanagi‑Jones wasn’t any more loyal to the Coalition than he was, and that it was his considered opinion that they should bring him in.

She sent Agnes back upstairs to fetch Kusanagi‑Jones while Katherinessen appropriated the cushions by her work surface. Kusanagi‑Jones appeared and stationed himself against the wall on the opposite side of the room, arms and ankles folded, still enough to go forgotten. Except for the slip of paper that Katherinessen had laid on her desk for examination, but would not permit her to touch.

Legally speaking, Kusanagi‑Jones couldn’tfight. Gentle or not, foreign or not, he was a male, and men didn’t duel. As she had expected, Katherinessen waited until she finished explaining and asked, “Then what’s the point in issuing a challenge?”

“He cost her face,” Lesa said. “Bad enough she’s in a delicate political situation for pandering to the Coalition–”

“Cost her face?” Katherinessen leaned forward, disbelieving. “He saved her life.”

“That iscosting her face.” Lesa pressed palms flat on either side of the indicted card, and wrinkled her nose at it. “You laid hands on her, which is illegal and a personal affront. If you were a stud male, it would go to Tribunal. Because you’re a gentle male, if an arraignment found no intent to harm, she could still challenge, and the women in your household would have the option of meeting it.”

“She can’t take him to trial,” Katherinessen said. “He has diplomatic immunity.”

Kusanagi‑Jones broke his silence without looking up. “Which is why she went straight to the challenge.”

“Precisely.” Lesa stood, turning her back on that cream‑colored card, and traced a hand along House’s interior curves as she walked away from the desk. “Do you want a drink?”

“Please,” Kusanagi‑Jones said with fervor.

Lesa turned, surprised, and pointed at Katherinessen. He nodded and held up two fingers.

Ice rattled into glasses. She dropped it from higher than necessary, for the satisfying thump. “It isn’t personal.”

Katherinessen frowned at his thumbnails while Lesa filled the glasses and waited, curling her toes into the carpetplant, waiting to see what he would logic out. He looked up and stood to take two glasses from her and pass one to Kusanagi‑Jones. “We…I…walked out of that assassination attempt with a PR advantage. She needs to nullify that.”

“Theft had to be a blow,” Kusanagi‑Jones added.

“Yes.” Lesa tested her drink. Too much ice. “And she can’t be seen to be beholden to the Coalition. And now it seems that you are willing to go to some risk to protect her.”

“She needs to shift the apparent relationship back to a more adversarial footing, or lose support. But why a challenge, when Angelo hasn’t got–”

“A woman to fight for him?” Kusanagi‑Jones said, rattling the ice in his glass. “You can say it.”

Lesa snorted. She came around the desk, easing the formality of the situation, and perched one hip on it, though the position made her holster pinch. “If he were Penthesilean, and no one in his house would stand up for him, Claude could take him in service.”

“Good way to get rid of unwanted houseguests.”

Katherinessen frowned over his shoulder. “But he’s not.”

“No. So if he can’t field a champion, he loses face as a…debtor who doesn’t meet his obligations. Claude looks tough on the Coalition and the two of you are sent home in disgrace, your viability as negotiators devastated. If I were a conspiracy theorist, I’d half‑bet she set up the assassination herself; it couldn’t better suit her needs. How long would it take the Coalition to scrape up another team?”

“Of ‘gentle’ males? How long do you think? So it’s a stalling tactic.”

“Precisely.” Lesa slammed the rest of her drink back and dropped the glass on the edge of the desk.

“But if she wants the rest of the art repatriated–”

“Look.” Lesa wiped her mouth with the back of her hand. “She’ll leap on the opportunity to keep Coalition agents off New Amazonian soil; she never wanted you here in the first place, whatever face she gave the Coalition. So she splits the difference, if I know Claude. She stalls and bribes and cajoles and commits diplomacy by packet bot rather than facing an immediate threat. And moreover, making you look uncivilized reflects on public opinion regarding the Coalition.”

“Charming. We’re deadbeats. We’re going to be very popular with the Coalition Cabinet when we get home.”

“If you can’t, as I said, field a champion.”

“Well, I can’t fight for him–” Katherinessen blinked. He sipped his drink thoughtfully and stared at the glass after he lowered it from his mouth. “You can’t be serious.”

“You could ask.”

The stretch of that silence gratified. “You’d shoot Claude Singapore for me,” Kusanagi‑Jones said after several ticks.

She grinned. “I’d shoot Claude Singapore on general principles. Actually, it’s perfect. We use her attempt to discredit you to discredit or kill her. Much more efficient than a vote of no confidence.”

Katherinessen rubbed his fingers together, unconvinced. “And if she kills you?”

She wondered if he knew just how unlikely that was. From the worried press of his lips, she didn’t think so. “Deal with my mother and Elder Kyoto, then. And get Julian off‑planet.”

“Your son.”

“He deserves better than I can get him here. He’s a very smart boy.” She paused, looked down, and swept her hand across the surface of her desk. “Take him to Ur. That’s my price.”

She hadn’t expected Katherinessen to pause and turn, and give that slow, considering look to Kusanagi‑Jones. Whatever Kusanagi‑Jones’s expression disclosed in return, Lesa couldn’t read it, but it seemed to satisfy Katherinessen.

“All right,” he said, when he looked back. “I’ll try.”

Which was the best he could honestly offer. She waited a beat, to see if anything else was forthcoming, and nodded twice. “At least if I win, it saves us staging a coup.”

“Sure,” Katherinessen replied. “All we have to do is fix an election. And provoke a revolution.”

Lesa smiled, nudging the still‑cold glass farther from the edge of the desk with the backs of her fingers. “Or two.”

Kusanagi‑Jones buried his face in his glass and breathed deeply, letting eye‑stinging fumes chase his muddleheadedness away. “How did you two make contact?” he said to Vincent.

“New Amazonia turns out to be a hotbed of political unrest.” Vincent scratched the back of his neck, wincing. Kusanagi‑Jones had to lace both hands around the glass in front of his groin to keep from reaching to stop Vincent’s hand as he said, “Who’d guess? But Lesa hasn’t told you the best part.”

Kusanagi‑Jones lifted his chin. “Suspense is killing me.”

“As I mentioned in the car, Robert’s vanished. The bad news is, he was the primary contact between Vincent and myself. Unfortunately, he was also working for Elder Kyoto, who, we learned last night, is secretly involved in a radical male‑rights movement called Parity.”