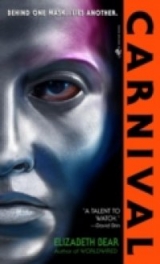

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

Her eyes widened; he tried to decide if it was calculated or not. From the shift of Vincent’s weight, he thought so. “Miss Pretoria hasn’t taken you to see the frieze yet?”

“There hasn’t been time.” Miss Pretoria slid between them, a warning in the furrow between her eyes. Interesting.

“No,” Vincent said. Vincent didn’t look up, apparently distracted by the vegetables, but he wouldn’t have missed anything Kusanagi‑Jones caught. His nimble fingers turned and discarded one or two more slices before he abandoned the plate untasted on a side table.

Elder Montevideo showed her teeth. Kusanagi‑Jones couldn’t fault New Amazonian dentistry. Or perhaps it was the apparent lack of sweets in the local diet.

“After dinner?” she asked, a little too gently.

Kusanagi‑Jones could still feel it happen. Vincent’s chin came up and his spine elongated. It wasn’t enough motion to have served as a tell to a poker player, but Kusanagi‑Jones noticed. His own tension eased.

Vincent had just clicked. He was on the job and he’d found his angle. Everything was going to be just fine.

Vincent tasted his lips. “Perhaps instead ofdinner?” he said lightly, a quip, beautiful hands balled in his pockets.

“The food isn’t to your liking, Miss Katherinessen?”

Vincent’s shrug answered her, and also fielded Kusanagi‑Jones’s sideways glance without ever breaking contact with Singapore. “We don’t eat animals,” he said negligently. “We consider murder barbaric, whether it’s for food or not.”

Perfect. Calm, disgusted, a little bored. A teacher’s disapproval, as if what he said should be evident to a backward child. He might as well have said, We don’t play in shit.

Michelangelo’s chest was so tight he thought his control might crack and leave him gasping for breath.

“Strange,” Montevideo said. The prime minister–Singapore–towered over her, but Elder Montevideo dominated their corner. “I hear some on Coalition worlds will pay handsomely for meat.”

“Are you suggesting you support illegal trade with Coalition worlds?” Vincent’s smile was a thing of legend. Hackles up, Montevideo took a half‑step forward, and he was only using a quarter of his usual wattage. “There’s a child sex trade, too. I don’t suppose you condone that.”

Montevideo’s mouth was half open to answer before she realized she’d been slapped. “That’s the opinion of somebody whose government encourages fetal murder and contract slavery?”

“It is,” Vincent said. He pulled his hand from his pocket and studied the nails. Montevideo didn’t drop her gaze.

Kusanagi‑Jones steadied his own breathing and stretched each sense. Every half‑alert ear in the room was pricked, every courtier, lobbyist, and spy breath‑held. Elder Montevideo’s hand was not the only one resting on a weapon, but it was hers that Kusanagi‑Jones assessed. Eleven‑millimeter caseless, he thought, with a long barrel for accuracy. Better to take Vincent down, if it came to it, risk the bullet on his own wardrobe and trust that the worried, level look Miss Pretoria was giving him meant she’d back his play if the guns came out.

He wondered about the New Amazonian rules of honor and if it mattered that Vincent was male and that he didn’t seemarmed.

And then Vincent looked up, as if his distraction had been a casual thing, and gave her a few more watts. He murmured, almost wistfully, “Now that we’ve established that we think each other monsters, do you suppose we can get back to business?”

She blinked first, but Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t let himself stop counting breaths until Claude Singapore nudged her, and started to laugh. “He almost got you,” Singapore said, and Montevideo tipped her head, acknowledging the touch.

Just a couple of fairies. He gritted his teeth into an answering smile. Apparently, it would have been thought a victory for Vincent if he provoked the woman enough to make her draw. A Pyrrhic victory, for most men in their shoes–

Singapore glanced at her watch–an old‑fashioned wristwatch with a band, external–and then laced her right hand through Montevideo’s arm. “We’ll be wanted upstairs.”

Vincent fell in beside her and Kusanagi‑Jones assumed his habitual place. He didn’t think Singapore was used to looking up to anybody, and she had to, to Vincent. “What I’d like to do instead of dinner is get a look at your power plant.”

“Unfortunately,” Singapore said, “we can’t arrange that.”

“Official secrets?” Vincent asked, not tooarchly. “We’ll have to talk about it eventually, if we’re going to work out an equitable trade arrangement.”

Kusanagi‑Jones could have cut himself on Singapore’s smile. “Are you suggesting that the Cabinet will resort to extortion, Miss Katherinessen? Because I assure you, the restoration of our appropriated cultural treasures is a condition of negotiation, not a bargaining chip.”

She ushered them through the door. A half‑dozen people around the room disengaged themselves from their conversations and followed them into the hall.

“It would make a nice gesture of goodwill,” said Vincent.

And Elder Singapore smiled. “It might. But you can’t get there from here.”

The route to the dining room wound up a flight of stairs and across an open footbridge, almost a catwalk. Kusanagi‑Jones breathed shallowly; his chemistry was mostly coping with the alien pollen, but he didn’t want to tax it. He leaned on Vincent’s arm lightly as Vincent fell back beside him. “Why are we antagonizing the people in charge?”

“Did you see Montevideo glance at her wife?”

Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t bother to hide his shrug.

“They’re not the ones in charge. Maybe a little fire will draw the real negotiators out.” Vincent paused and smiled tightly. “Also, aren’t you curious why they wanted us to see these friezes and Miss Pretoria was all a‑prickle about it? Because I know I am.”

Kusanagi‑Jones’s hands wanted to shake, but he wouldn’t let them. They entered a banquet room, and he saw Vincent seated on the prime minister’s left and took his own seat next to Miss Pretoria, touching the glossy wood of the chairs and table as if he were used to handling such things. He sat, and discussed his dietary needs with Pretoria, then allowed her to serve him–which she did adroitly. The food was presented family style, rather than on elaborately arranged and garnished plates, whisked from some mysterious otherworld to grace the incredible solid wooden table.

There werevegetarian options, although most of them seemed to contain some sort of animal byproducts. But the scent of charred flesh made eating anything–even the salad and the bread with oil and vinegar that Miss Pretoria assured him was safe–an exercise in diplomatic self‑discipline. It smelled like a combat zone; all that was missing was the reek of scorched hair and the ozone tang of burned‑out utility fogs.

The cheese and butter and sour cream were set on the table between plates laden with slices of roasted animal flesh, like some scene out of atavistic history–the sort of thing you expected to find in galleries next to paintings of beheading and boiling in oil and other barbaric commonplaces. Michelangelo brushed his sleeve up and touched his watch again, adjusting his blood chemistry to compensate for creeping nausea, and kept his eyes on his own plate until he finished eating.

He shouldn’t be huddled in his shell. He should be talking with Miss Pretoria and the assembled dignitaries, walking the thin line between interest and flirting. He should be watching the women–especially Elena Pretoria, a grande dame if he’d ever met one, and most likely Lesa Pretoria’s mother–and the two reserved, quiet men at the table, picking out what he could about the social order, trying to understand the alliances and enmities so he could exploit them later.

The women seemed interested in Vincent and himself–by which he meant, attracted to–and a glance at Vincent confirmed he thought so, too. Elders Singapore and Montevideo were the obvious exceptions to the rule. They had eyes only for each other, and Kusanagi‑Jones might have found it sweet if he hadn’t suspected they’d cheerfully have him shot the instant he wasn’t conforming to their agenda.

The more he watched Montevideo, the more he thought–despite her apparent spunk–that she was like politicians’ wives everywhere: intelligent, intent, and ready to defer–at least publicly–to her mate’s judgment. Vincent was right; she looked at Singapore every time she said something.

Kusanagi‑Jones bit his lip on a pained laugh; he recognized no little bit of himself in her behavior.

It didn’t hurt that Vincent was now paying an outrageous and obviously insincere court to the prime minister that still seemed to entertain her enormously. She had switched to treating them like indulged children; Kusanagi‑Jones found it distasteful, but Vincent seemed willing to play the fool. The women were asking interested questions about the Colonial Coalition, seeming shocked by things in absolute disproportion to their importance.

Montevideo was particularly fascinated by eugenics and population‑control legislation, and kept asking pointed questions, which Vincent answered mildly. Kusanagi‑Jones pushed his plate away, unable to face another mouthful of red‑leaf lettuce and crispy native fruit mixed with imported walnuts. It wasn’t so bad when he wasn’t trying to eat, and it was amusing to eavesdrop as Montevideo tried to get a rise out of Vincent.

“Well, of course the Cabinet tries to limit abortions,” Vincent was saying. “Ideally, you control population through more proactive means–” He shrugged, and speared a piece of some juicy vegetable that Kusanagi‑Jones couldn’t identify with a perfectly normal Earth‑standard fork–except Kusanagi‑Jones would bet the forks were actual metal, mined and refined, and not fogs. “But even medical bots fail, or can be made to fail. Biology’s a powerful force; people have a reproductive drive.”

“You don’t think… peoplecan be trusted to make their own decisions, Miss Katherinessen?” Arch, still sharp.

Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t need to look at Vincent to know he would be smiling that wry, gentle smile. He looked anyway, and didn’t regret it, although Vincent’s expression made it hard to breathe. Again. Dammit.

He could not afford to care, to trust Vincent. He was here to destroy him. New Earth, all over again. Only worse this time.

“No,” Vincent said, as Kusanagi‑Jones picked the remainder of his bread apart. “We evolved for much more dangerous times, and memory is short. Just because Old Earth survived pandemics and famines and Assessments during the Diaspora to achieve a few modern ideas about stewardship doesn’t mean that enlightenment trickles down to everybody. And it’s very hard for most people to postpone an immediate want for a payoff they won’t see, and neither will their grandchildren.”

“Thus the Governors,” Elder Montevideo said, folding plump, delicate hands. The prime minister watched, silently, and so did Elder Pretoria, who was seated at the far end of the table.

“The Coalition,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, to demonstrate solidarity. He would notshow pain. “So the Governors don’t intervene again on a large scale. They arestill watching.”

He knew better than to attempt Vincent’s trick of speaking as if to an idiot child, but it was tempting.

“The Coalition isn’t allied with the Governors, then?” asked one of the other women at the table, an olive‑skinned matron with cool hazel eyes who never stopped smiling. Elder Kyoto, if Kusanagi‑Jones had the name right. He’d logged it; he could check his watch if needed.

“The Coalition is interested in…minimizing the impact the Governors have on human life. And the Governors permit the Coalition Cabinet that latitude.”

“And the Governors must be prevented from intervening?”

“If you know your history.” Vincent smiled right back. “It keeps us on our toes.”

Elder Singapore covered her partner’s hand with her own. “If it wasn’t for Diaspora, New Amazonia wouldn’t be here. And we would be robbed of the pleasure of each other’s company. Which would be a great pity indeed.”

Vincent asked, “Was yours one of the private ships?”

“The Colony craft? Yes. Ur was also, wasn’t it?”

He turned his fork over as if fascinated by the gleams of light on the tines. “My great‑grandmother was disgustingly rich. It was an experimental society, too. The colonists were all pregnant women. No men. And there was a religious element.”

Elder Montevideo leaned forward, although she wasn’t quite overcome enough to rest her elbows on the table. “What was the purpose of the experiment?”

“To prove a point of philosophy. To establish an egalitarian matriarchy based on Gnostic Christian principles.” He glanced up, twinkling. “My mother is the only woman on the Colonial Coalition Cabinet. We’re not so different.”

She sat back, picked up her silver knife, and gave minute attention to buttering a roll. “Our founding mothers believed that it was possible to live in balance with nature,” she said. “And by balance, they did not mean stasis. They meant an evolving dynamic whereby both the planet’s Gaian principle and her population would benefit. Not exploitation, as it was practiced on Old Earth: women do not exploit. We take care when we practice forestry, for example, to leave renewal niches, and we practice sustainable agriculture and humane animal husbandry.” The knife went down with a clink. “Of course, the impact of our activities is attenuated because we didn’t need to bootstrap through a fossil‑fuel economy. We’ve been fortunate.”

At least they know it,Kusanagi‑Jones thought. He sipped his wine and watched her eat.

“I’m curious,” Vincent said. “Something you said earlier hinted to me that you find eugenics distasteful.”

Miss Pretoria laughed out loud and glanced at the prime minister for permission to continue. Kusanagi‑Jones saw the elder Pretoria lean forward, but she still held her tongue. A watcher.Dangerous, if the mind was as sharp as the eyes. “If Old Earth gave women reproductive autonomy, I don’t believe you’d have a population problem. Wedon’t–”

“ Youhave an undamaged ecosystem,” Kusanagi‑Jones said. Vincent might have been the one to guess that a bold‑faced refusal to temporize was one way to earn their respect, but Kusanagi‑Jones wasn’t too shy to capitalize on it. Vincent didn’t quite smile, but the approval was there between them, warm and alive. “For now, at least, until you overrun it.”

Kusanagi‑Jones, who had been about to continue, closed his mouth tightly as Elder Montevideo spoke. “One of the reasons our foremothers chose to emigrate was because of Earth’s eugenics practices. They did not feel that a child’s genetic health or sexual orientation determined its value. Do you,Miss Kusanagi‑Jones? Miss Katherinessen? Because I assure you, the mothers at this table would disagree.”

Vincent’s eyes were on Montevideo, but Kusanagi‑Jones could tell that his attention was focused on Miss Pretoria. And even Kusanagi‑Jones could feel her discomfort; she was buzzingwith it. “I think,” Vincent said, carefully, “the health of a system outweighs the needs of a component. I think prioritizing resources is more important than individual well‑being.”

“Even your own?” Miss Pretoria asked, laying down her fork.

Vincent glanced at her, but Kusanagi‑Jones answered.

“Oh, yes,” he said, directing a smile at his partner.

He was a Liar; neither his voice nor his expression betrayed the venom he’d have liked to inject into them. He projected pride, praise, admiration. It didn’t matter. Vincent would know the truth. It might even sting. “Especially his own.”

Lesa shouldn’t have been taking so much pleasure in watching Katherinessen bait Maiju and Claude, but her self‑control was weak. And a small gloat never hurt anyone,she thought. Besides, even if the enemy of Lesa’s enemy wasn’t necessarily Lesa’s ally, the prime minister richly deserved to be provoked–and in front of Elena. Lesa saw what Katherinessen was playing at. He lured them to underestimate and patronize, while picking out tidbits of personal and cultural information, assembling a pattern he could read as well as Lesa could have.

He was also staking out space, while getting them to treat him like a headstrong male. Clever, though confrontational. Lesa often used the same tactic to manipulate people into self‑incrimination.

Just when she thought she had their system plotted, though, Kusanagi‑Jones turned and sank his teeth into Katherinessen, hard. And Lesa blinked, reassessing. A quick glance around the table confirmed that only she had caught the subtext. And that was even more interesting–a hint of tension, a chink in their unity. The kind of place where you could get a lever in, and pry.

She wondered if Kusanagi‑Jones was aware of Katherinessen’s duplicity, and if he was, if Katherinessen knewhe was aware, or if there was a different stress on the relationship. They’d been apart for a long time, hadn’t they? Since New Earth. Things changed in seventeen years.

Then as fast as it had been revealed the flash of anger was gone, and Lesa was left wondering again. Because it was possible she’d been intended to see it, that it was more misdirection. They were good enough to keep her guessing, especially when Katherinessen smiled fondly across the table at Kusanagi‑Jones, not at all like a man acknowledging a hit.

Lesa was aware of the other dynamics playing out around the table. They were transparent to her, the background of motivations and relationships that she read and manipulated as part of her work, every day. But none of them were as interesting as Katherinessen and Kusanagi‑Jones. Their opacities, their complexities. She could make a study just of the two of them.

And something still kept picking at the edge of her consciousness, like Katherinessen picking at Maiju, like a bird picking for a grub, though she didn’t quite know what to call it. She wondered if they could have fooled her, if perhaps they weren’t gentle after all. The idea gave her a cold moment, as much for fear of her own capabilities eroding as for the idea of a couple of stud males running around loose.

Even the best of them–even Robert, whom she loved–were predators. Biologically programmed, as a reproductive strategy. Uncounted years of human history were the proof. In previous societies–in allrecorded societies, other than the New Amazonian–when a woman died by violence, the perpetrator was almost always male. And almost always a member of the woman’s immediate family, often with the complicity of society. The Coalition was a typical example of what men did to women when given half an excuse: petty restrictions, self‑congratulatory patronization, and a slew of justifications that amounted to men asserting their property rights.

Two stud males–if they were,and she honestly didn’t think so–on the loose and unlicensed in Penthesilea were unlikely to bring down society. But by the same token, Lesa wouldn’t let a tame fexa run loose in the city. There was always the chance somebody would get bitten.

The irony of that concern, compared to the gender treason she was plotting, made her smile bitterly.

“Miss Pretoria,” Katherinessen said, as the waiter removed his plate, “you’re staring at me.” He hadn’t looked up.

“Are there circumstances under which the well‑being of a minority doesmatter? Circumstances of gross injustice?”

“Oppression? Such as the status of men on New Amazonia?”

Elder Kyoto, the minister of security, waved her fork. “There are sound behavioral–”

“Just so,” Claude said. The other guests went quiet. “Or what the Coalition would like to do to New Amazonia, to bring it under hegemony. Setting all that aside for the moment–as civilized people should be able to do”–and it seemed to Lesa that Claude reserved a particularly bland smile for Kusanagi‑Jones–“is it still an interesting question on its own merits?”

Katherinessen steepled long fingers. Dessert was being served. He declined a pastry just as Lesa warned them that there was most likely butter in the crust, but both males accepted coffee without cream.

Katherinessen tasted the coffee as soon as it was set before him, buying a few more moments to consider his answer and unconcerned with his transparency. “Whichever group is in ascension at a given moment is, historically speaking, both unlikely to acknowledge even the existenceof abuses or bias, and also to justify the bias on any grounds they can–social, biological, what have you. May we agree on that?”

Claude’s smile slid from bland toward predatory. “Mostly.”

“Then let me raise a counterquestion. Do you believe an egalitarian society is possible?”

“Define egalitarian.”

“Advancement based solely on merit.” Katherinessen smiled at his partner, who was stolidly stirring his coffee over and over again. “As Angelo is fond of pointing out to me, I have certain advantages of birth. My family is well regarded in society on Ur. By comparison, on Old Earth before Assessment, any of us would have been disadvantaged due to our skin tone–if we lived in the industrialized world.”

“Protected by it, later,” Kusanagi‑Jones said under his breath. He was leaning on the arm of his chair, toward Lesa; she thought she was the only one who heard it.

Claude didn’t answer immediately. She nodded around the excuse of a bite of pastry, forked up in haste, as if inspecting Katherinessen’s words for the trap. “So even Assessment wasn’t an equalizer. Not a fresh start.”

“It was the opposite of an equalizer.” Katherinessen shrugged. “Each round of Assessed were chosen on the grounds of arbitrary standards programmed into the Governors before they were released. It was the epitome of unnatural selection, for an elite. Agriculturists, scientists, engineers, programmers, diplomats, artisans, and none of them Caucasian–what more arbitrary set of criteria could you imagine for survival?”

Lesa laid her fork down. “I don’t believe equality exists.”

Elder Kyoto glanced around. “Why not?”

“Because Miss Katherinessen is right, but doesn’t take it far enough. Not only will whoever’s on top fight to stay there, but if you reset everyone to equality, whoever wins the scramble for power will design the rules to stay there.”

Katherinessen nodded. “So what do you think ispossible?”

“If I were the oppressed?”

A short pause, with eyebrow. “Sure.”

Lesa wondered if she could startle him. The Colonials didthink everybody on New Amazonia was an idiot, or at least naive. That much was plain. “Conquest. Revolution. Dynamic change would ensure that nobody ever wound up holding too much power. Fortunately for me, as a member of the ruling class, people tend to prefer the status quo to unrest unless they’re very unhappy. Which is why the Coalition isn’t entirely welcome here.”

She picked her fork up again and began flaking apart the buttery layers of pastry, not so much eating as pushing them around on the plate to cover the gilding. Katherinessen sighed. She thought it was satisfaction. She didn’t want to feel the answering glow in herself, as if she’d just done well on a test.

“You are so very right.” Katherinessen glanced at Kusanagi‑Jones, who had stopped stirring his coffee, but wasn’t drinking.

“You know what they say,” Kusanagi‑Jones quipped. “Dйtente is achieved when everybody’s unhappy.”

The bipeds communicate. There are the new ones, the males in their dual‑gender system. Kii supposes one biologically convenient system for randomizing genetic material is as good as another, but the bipeds also use theirs as a basis for an arcane system of taboos and restrictions. At first Kii thinks this is adaptively obligated, that the child‑bearing sex was responsible for the protection of the offspring, and the society was structured around that need. There are local animals with similar adaptations–unlike the Consent, unlike the khir–where the greatest danger to cubs is posed by unrelated males, which prey on the offspring of other males.

Kii is startled to find an intelligent species retaining such atavistic tendencies. But then, Kii is also startled to find an intelligent species evolve without also evolving the Consent, or something like it. And since the territorial dispute, Kii is forced to acknowledge that no matter how developed their technology and aesthetics, the bipeds have no Consent.

Kii wonders if the other population of bipeds, encroaching again on the ones Kii thinks of as Kii’s bipeds, intend another territorial dispute. The timeslip is threads that converge and threads that part; patterns of interference. It is a wave that has not collapsed. The nonlocal population may transgress, driven, Kii thinks, by outstripping its habitat. There may be another dispute. The probability is not insignificant that the local population of aliens will be overrun. Kii is possessive of the aliens, and Kii’s possessiveness informs the Consent.

If the other population encroaches, Kii wishes to intervene again, more strongly than before. The Consent is not so sanguine.

Yet.

5

EVEN VINCENT WAS RELIEVED WHEN DINNER ENDED, though it segued without hesitation into another endless reception. This one at least had more the air of a party, and finally there were a number of other men present.

As soon as they left the table, the elder Pretoria cut Michelangelo off Vincent’s arm as neatly as impoverished nobility absconding with an heiress at a debutante’s ball. Despite Michelangelo’s long‑suffering eyeroll, he went, flirting gamely.

Vincent took this as a sign that the business portion of the evening had ended, and availed himself of the bar. He wasn’t going to get drunk–his watch would see to that–but he would examine the options. It would give him something to do with his hands while considering the evening’s haul.

He accepted the drink he’d pointed to in a moment of bravado–something greenish‑gold and slightly cloudy, a spirit infused with alien herbs, if his nose didn’t mislead him–and leaned into a quiet corner, for the moment observed by no one except the security detail, who appeared to be making sure he didn’t wander off.

It was a reversal of his and Michelangelo’s usual roles, but not an unpracticed one. Michelangelo could pretend to charisma as effectively as anything else, and dominate a room with ease. And the dynamics of an assembly such as this could be revealing. It was like watching a dance that was also combat and a game of chess.

Miss Pretoria, for example, was leaving a conversational cluster that included the person Vincent had tentatively identified as the minister of the militia–of Security, he corrected himself, which was a significant choice of title on its own–and crossing to the group that encompassed Michelangelo and Elena Pretoria, and a tall, beautifully dressed, dark‑skinned man with a shaved‑slick scalp. With whom, Vincent noticed, Michelangelo was now flirting. Vincent’s fingers curled on his glass, and he pressed his shoulders against the warm, slightly vibrating wall of the building, feeling it conform to his body.

The prime minister and her entourage occupied a space that was more or less on the left center of the ballroom, and somehow managed to give the impression of being off in a corner–and one diametrically opposed to the Pretoria household at that. And there was something else interesting: as Lesa crossed the room, nobody wanted to catch her eye, despite her occasional nods and words she shared with those she passed. Unobtrusively, a path opened before her, but it wasn’t the standing aside of respect. It was a withdrawal. I wonder what she is when she’s not a tour guide and turnkey.

He dug his toes into the groundcover and watched. People could give themselves away in the oddest manners. Even simply by the ways in which they made sure of their guard. For example, the faint discomfort with which Lesa responded to a broad‑shouldered, bronzed man who entrapped her a few steps from the relative haven of her mother’s enclave. He had long hair cut blunt at his shoulders, the fair, blondish‑brown color and coarse wavy texture even more unusual than Vincent’s auburn, and his hands were knotted whitely with old scars. He spoke softly, eyes averted, and Lesa reached out and tucked a strand of that wonderful hair behind his ear in a good counterfeit of flirtation before excusing herself to join her family.

Vincent was just finally getting around to paying some attention to his drink when the minister of Security–the one who had been about to bring biology into the dinner argument until Singapore shut her down–appeared at his elbow. “Miss Katherinessen,” she said, mispronouncing his name kath‑er‑in‑ES‑sen,“I’m sorry to see you’ve been abandoned.”

She held out her hand and he took it gingerly. The wine on her breath bridged the distance between them easily. The New Amazonian disregard for personal space, but also something more.

He would have stepped back, but he was already against the wall. “I’m self‑amusing,” he said, and met her gaze directly, the way Penthesilean men did not.

She edged closer, oozing confidence. She expected him to be intimidated and perhaps flattered as she laid her hand on his arm. He’d seen the expression on her face on enough old warhorses cornering sweet young things at embassy parties: a predator gloating over trapped prey.

He was supposed to blush and look down, and maybe sidle away. Instead, he pictured Michelangelo standing where he was standing now, and burst out laughing.

She stepped back, abruptly, covering her discomfiture with a scowl. “I wasn’t aware I was so amusing.”

“Actually,” Vincent said, stepping around her now that he’d bought himself room, “I find the corner by the door’s the best place to be. Are you attending the ceremony tomorrow, Elder?”

He turned to face her, which put his own back to the room–but that wasn’t too unsettling when Michelangelo had it covered. And now she was the one trapped against the wall, which was a tactical gain.

“I wouldn’t miss it,” she said. “We’ve arranged a meeting with some technical specialists afterward, who can explain what we’re prepared to offer for our part of the deal. I’m sure Lesa’s made sure you have a copy of the schedule.”