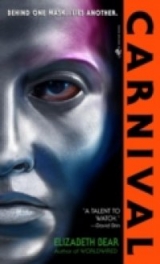

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

She paused before the lift rather than heading for the stairs. Just as well, because Vincent didn’t fancy carrying her up them, and Michelangelo’s feet were in no shape for chivalry.

Stubborn or not, Lesa was swaying by the time she stopped, and Vincent steadied her with a hand on her shoulder as he commanded the lift. The venom had left her weak, febrile, and probably aching. Inside the lift, she propped herself on him without seeming to, and he smiled as he tilted toward her. He hadn’t slept in days, and though he still had chemistry it was wearing thin. If Michelangelo was too proud to lean, Vincent wasn’t.

The lift brought them to the third floor, and Lesa paused before the doors to her bedroom. “Excuse the mess,” she said, and gestured them inside.

Michelangelo went first, covering Vincent, and for once Vincent reveled in it rather than chafing. But there was no one inside except a sleepy khir in a basket, who lifted his ear‑feathers at them but seemed otherwise disinclined to stir. Vincent recognized Walter by his bandages and almost thought the khir grinned at him–if khir grinned.

He turned to assist Lesa in managing her crutches through the door, but she didn’t need him. She clumped to her bed and flopped down, letting the crutches slide to the carpetplant alongside. She closed her eyes, face sallow with pain, and didn’t seem to notice when Angelo bent down, picked up the crutches, and silently braced them upright against the wall between her bed and her nightstand.

“All right,” she said. “This is as private as I can manage on short notice.”

Vincent nodded and raised his eyes to the wall. “Kii, would you introduce yourself to Miss Pretoria?”

The swirling effect in the wall panels was just as before, though Vincent noticed that Lesa had turned off the jungle scenes in this room, leaving blank taupe walls. First eyes and then a tall lithe body coalesced from swirling pixels, and Kii lay at ease, its wings folded comfortably along its sides so it could recline on its elbows. It settled its plumed head between its shoulders like a somnolent bird and blinked at them.

“Greetings, Lesa Pretoria,” it said. “Greetings, Vincent Katherinessen and Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones. Kii anticipates your questions.”

At the sound of the mellow, neutral voice, Lesa lurched upright on the bed, hands braced to either side. “Dragon,” she said, and shook her head, many‑colored hair flying around her.

She looked to Michelangelo, not Vincent. “Simulation?”

“Transcended,” Vincent answered, when Michelangelo didn’t. “Kii, Michelangelo would like to accept your offer of medical treatment.”

Kii’s head settled more solidly between ridged shoulder blades. “Michelangelo, is that so?”

Michelangelo kept his eyes straight ahead, though Vincent was waiting for the glance. “Yes, Kii.”

“It is done,” Kii said. “You will find a document for your life support device available in the datastream. It should enable your implants to locate and eradicate the infection.”

“Kii,” Vincent said, “can you tell me where to find the lab where that virus was tailored?”

“It is not within Kii’s range of access,” Kii said. It angled its head and stretched its neck, as if regarding Lesa more closely than before. “The khir like you, when you come. The Consent is that you may stay, to please the khir. We are fond of the khir. And Kii is grown fond of you.”

Lesa sat very still, the bedclothes knotted in her hands. She licked her lips, pulse visible at her throat, and Vincent found himself in sympathy with her nervousness. The Dragon’s regard had a tendency to make him feel like a snack, as well.

“That’s you‑humans, not you‑Lesa?” Michelangelo, surprising Vincent.

“The khir approve of Lesa Pretoria,” Kii said, the long neck swaying slightly, plumage ruffled by an unseen breeze.

In his basket, Walter flopped on his side and hissed, showing his belly to the air. Lesa turned her head and looked at him, leaning forward on the bed without lowering her feet to the floor. Not trying to stare the Dragon in the eye seemed to ease her. Vincent remembered some Old Earth legend about snakes and hypnosis, or maybe turning people into stone.

“The khir really aren’t smart enough to…talk…are they?” she said. Walter lifted his head, neck craning around like a hand puppet, and blinked back at her with triangular‑pupiled eyes.

It was that look that did it. He’d been telling himself, over and over, that his gift shouldn’t apply to Dragons or to khir. That their kinesthetics, their everythingwas different from that of humans, and deceptive.

But that intellectual knowledge hadn’t stopped him from reading them, and reading them correctly–Dragon and khir.

Because the khir had been living with New Amazonians for 150 years, and the khir–nonverbal, with a predator’s extended jaw structure and limited facial expressions–were quite perfectly capable of communicating through kinesthetics, the rise and fall of their peculiarly expressive plumage that ruffled independent of any wind.

Just as the Dragons must have, when they were meat.

“Actually,” Vincent said, “I think the khir tell the Dragons rather a lot, don’t they?”

“The khir are invaluable,” Kii said. “They are the protectors of the old world. We make them safe denning, and they give the city purpose. As now you do as well.”

“Because the city is esthelich,isn’t it?”

“That can be no revelation, Vincent Katherinessen.”

“No,” Vincent said, aware of Michelangelo shifting a half‑step closer to him, a warm pressure at his elbow. “I’ve known that for a while. Since it helped me hide from the kidnappers. If it’s esthelichby your standards, it must have an aesthetic. And its aesthetic is…comfort? The care of its inhabitants?”

“Would you create a domicile that thought otherwise?”

“No.”

Lesa had looked away from Walter and was now sitting curled forward, the bedclothes dragged over her lap as she stared at Vincent. “And of course,” she said, “even if you were Transcendent, there’s always the chance that something could go wrong with the system, isn’t there?”

Smart woman. Which was no more a revelation than House’s taste in art had been. “The possibility exists,” Kii said, hunching between its wings.

Vincent said, “And if you needed physical bodies again? Could you read your…personality onto an organic system?”

“The possibility exists.”

“The khir are a failsafe.”

“The khir are not disposable,” it answered, contracting again, pulling itself back on its haunches.

“Kii,” Michelangelo said. “If you had to translate esthelich. What would you say it meant?”

The Dragon hesitated. Its head swung side to side, the tongue flickering through a gap in its lower lip. “It does not translate into merely one of your words.”

“Try.”

“Fledged,” it said, with no weight of emotion on the word.

If Kii were human, Vincent would have scrupled to press. He would have known he was millimeters from a moral pit trap, a bit of doublethink that would expose a violent defensive reaction when triggered. But the Dragons had Consent. They were as physically incapable of experiencing moral qualms about following orders as Vincent’s own hand was of rebelling when his consciousness instructed it to pull a trigger.

He said, “They’re not a separate species, are they?”

And Kii shifted, its wings furled tight against its sides, and blinked slowly. “The khir? They are not.”

“They’re young Dragons. Neotenous. With their growth and intellectual development intentionally retarded.”

“They are not esthelich. They have no Consent. We provided for them, and they protect us.”

“That’s horrible,” Lesa said. She dropped the bedcovers and climbed to her feet, wincing as her bandages touched the carpetplant. “You…engineered your own children into slaves?”

“Pets…no, domestic animals are not slaves,” Kii insisted. “They are without aesthetic. They are not people. Your infant creatures are immoral–no. Sociopathic. They are not people.”

Vincent reached behind Angelo to put a hand on Lesa’s arm, steadying. She shook it off. “But they could have been.”

“Not these, no. They were conceived to this purpose, and they breed true. They are animals, and would never have been born, otherwise.”

“Unless you remove the, what, the chemical inhibition? And then they transform into adults. Only with the minds of Transcended Dragons downloaded into their skulls, rather than whatever they might have become?”

“It is,” Kii said, “the Consent.”

Lesa might have wanted nothing to do with Vincent, but Michelangelo stepped closer, shoulder to shoulder, and Vincent leaned on his warmth, their wardrobes melding. “What if we lobotomized girl babies,” Angelo said. “Kept them as cattle. Destroyed their higher functions–”

“They would not be esthelich,” Kii said. “They would be as domestic animals, as the khir. But it would be immoral to destroy the potential to be people in one born with it.”

“But the Consent finds no ethical failing in creating the khir?”

“The Consent finds no ethical failing in the selective breeding of domestic animals.”

“Lesa,” Angelo said, “please sit down. It hurts to watch you.”

She stared at him, head drawing back as her neck stiffened, and then she nodded and sank down on the unmade bed. “I have another question for the Consent,” Vincent said.

Kii lifted its chin, ear‑feathers forward to cup sound. Alert and listening.

“If you can reprogram Michelangelo’s docs, can you rewrite other code?”

“We can.”

“The Governors,” Vincent said.

And with a careful, human gesture, Kii shook its head. “It is discussed. The Consent is that it is unwise. And also that the Governors are not esthelich,but that they are art. And not to be destroyed.”

“Fuck,” Michelangelo said, and Vincent didn’t blame him. “Then it’s a war.”

24

THE MALES LEFT SHORTLY AFTER THE DRAGON DID, LEAVING Lesa alone in her bedroom with the sleeping khir. Michelangelo wouldn’t let her rise to see them to the door, his stern glower as effective as a seat belt, but hiding a striking chivalry that Lesa wouldn’t pretend not to chafe at and couldn’t understand how she’d earned. It still carried a taint of chauvinism, but Michelangelo seemed to think it indicated respect.

It didn’t matter. He was trying to learn, to accommodate. And she’d have fought for him even if he wasn’t. Her own honor was at stake now.

When the door spiraled closed behind Vincent and Michelangelo–and stayed closed; Lesa was wise to that trick–she pried herself off the bed again and settled wearily on the carpetplant beside it. The pain was bad enough, though analgesics and anti‑inflammatories were some use–but the vertigo was truly incapacitating.

She could live with pain.

Her citizenship piece was still missing. Lost to her forever, probably, along with her daughter and her mate. But she had more than one weapon and it wasn’t as if she could go about unarmed. There was a pistol and an old holster in the bottom of the nightstand.

Lesa pulled the box out, inspected the weapon–clean and smelling muskily of gun oil–and strapped the soft, worn leather of the gunbelt around her waist. Then she loaded the honor, safetied it, and laid it on the bed. It took the same caseless ammunition as her citizenship piece.

Standing was unpleasant. But she couldn’t settle the holster properly while hunched on the floor, and whatever bravado she’d issued to the males about not needing to be able to walk to shoot, she had to be able to stand to duel.

She slipped her new honor into the holster, checked twice to make sure it was locked and no round was chambered, and pulled one of the crutches away from the wall to brace herself on.

“House,” she said, “I need a mirror.”

The long interior wall with no doorways was her usual mirror. It misted gray and glazed reflective as Lesa limped toward it, transferring as much weight to the crutch as possible to keep it off her feet. She paused two meters from the wall and stared at her reflection in true color.

She looked like ragged death. Her face was puffy around the scratches and shiny with antibiotic ointment. Her hands were red‑fleshed and torn, her forearms more scab than skin. She wobbled, and leaned against the crutch hard enough that her whole body canted left. The fingers of her right hand, hovering over the butt of her honor, looked like undercooked sausages, and the gouges on her palm had cracked open again and were leaking pinkish fluid.

“I am,” she whispered, “so fucked.”

The draw was reflex, wired into nerve and muscle by decades of practice. She shouldn’t have to think about it. She should barely be conscious of feeling it happen.

The air dragged at her wrist, thickened around stiff fingers. The hand was slow, the fingers inflexible; they didn’t hook the butt of the honor and glide inside the trigger guard as they should. The weight was wrong, the balance off–

Her honor skipped from her hand, spinning, and hit with a thud butt‑first on the carpetplant, tottering a moment before toppling onto its side. The crutch skipped, and Lesa hit a split second later, down on one knee, her right hand slamming the floor with all her weight behind it.

The pain was asphyxiating. She fought for breath–diaphragm spasming, the gasp more like a whine if she was being honest–and blinked until her vision cleared. And then she picked up her honor, holstered it, found the crutch left‑handed, and forced herself up, to face the mirror again.

The twenty‑fifth attempt was no more successful than the third.

Pain couldn’t force her to stop, but eventually the bleeding and nausea did. She holstered her honor one last time, resettled the crutch under her armpit, and hobbled to the balcony. Julian was still down there with the other boys, running and laughing. The echoes of his voice carried to her room before she stepped outside, and she found a smile for that. The only thing he loved better than handball was his numbers.

Lesa hitched to a stop a few steps shy of the railing. She stared down, at the running children, at the watching tutors. Her gouged hand tightened on the crutch; she barely noticed.

She took two steps back, into the frame of the doorway. “House,” she said. “I need to speak to Julian. Please have Alys send him down.”

When Lesa summoned them again, even Kusanagi‑Jones could tell she had not been resting. Her color was worse, her hair tangled and the knees of her trousers stained with chlorophyll. And then there was the matter of the slender dark boy curled on the seat before her terminal, pecking at the keys with concentrated precision.

“Miss Pretoria?”

She gave him that eyebrow, but stepped aside to allow him into the room, Vincent at his heels. The door clicked as it contracted shut behind them, and Kusanagi‑Jones paused and glanced over his shoulder. Vincent caught him looking, of course, eyebrows quirked and the faintest hint of a smile–an expression that slid through Kusanagi‑Jones’s heart like a skewer. He would have sworn he could feel the muscle contracting around penetrating metal, trying to beat and only managing to shred itself a little further.

Three months, on the Kaiwo Maru. Three months they could have had. And he had been too much of a sodding coward to even reachfor it.

Then Vincent’s half‑smile turned into a real one, as if he knew exactly what Kusanagi‑Jones was thinking, and loved him for it, or in spite of it. And Kusanagi‑Jones smiled back.

So it went.

Kill or be killed.

Vincent took him by the elbow and steered him into the room. “You have the look of a woman with a plan,” Vincent said, and the corners of Lesa’s eyes crinkled, an expression that made Kusanagi‑Jones homesick.

“Can you shield this room?” she asked.

“Shield it from what?”

“Electromagnetic monitoring.”

Vincent glanced at Kusanagi‑Jones, who looked right back, silently. “Yes,” Vincent said. He touched his watch. “The whole room?”

“It’d be more convenient. I’ve already isolated it from House.”

“Angelo?”

Kusanagi‑Jones nodded, and slaved his wardrobe to Vincent’s. Between them, they had enough foglets to manage a Faraday cage, since their wardrobes–given time–could manufacture more as needed.

The process took a few minutes, and Lesa said nothing further throughout, which seemed an indication for communal silence. “There,” Vincent said when it was done. “I’ve added eavesdropping countermeasures.”

Lesa didn’t answer. Instead, she stared at Kusanagi‑Jones and asked, “Did you download Kii’s medical program?”

“He did,” Vincent answered.

“Do you still have it?”

Julian, who hadn’t spoken, came up beside Lesa, close enough to feel her body heat without the childish admission of actually touching her or stepping behind her. Kusanagi‑Jones looked at him, not at Lesa, and held up his left arm, stripping the sleeve off the forearm to show the status lights on his watch. Only one blinked green now, the slow flicker of the nanodoc condition readout. The rest glowed red or dark amber, for critical infection.

There was more amber than there had been an hour before, and not just because Kusanagi‑Jones had grabbed a nap.

“I need that,” Julian said.

Kusanagi‑Jones let his arm fall, and his sleeve drop over it. “The program?”

“A copy of it.” He shuffled forward, forgetting that he had been half hiding behind his mother, and grabbed Kusanagi‑Jones’s wrist to pull him toward the terminal.

Bemused, Kusanagi‑Jones was about to step forward and follow, until Julian froze and turned back, gazing up at Vincent with stricken eyes.

Vincent, sod him, was waiting for it. He smiled at Julian and waved him away, Kusanagi‑Jones included.

Nice to know I’ve still got his mark stamped between my eyes.But he went, as Vincent must have known he would.

“What frequency does it use?” Julian asked, and Kusanagi‑Jones told him. And then queued and transferred the archive copy of Kii’s program as soon as the protocol connected.

“What exactly are you planning?” Vincent hadn’t done more than step sideways and lean back against the wall before the door. Kusanagi‑Jones knew without turning that his chin would be dropped insouciantly toward his chest, his ankles crossed.

“Julian’s been working on quantum decision trees,” Lesa said.

“Fractal,” Julian corrected, without looking up from his displays and the holographic array floating in the air before him. “Fractal decision trees.”

“Which means what, in layman’s terms?” It almost sounded as if Vincent knew what was going on. Which was fine with Kusanagi‑Jones, because he certainly didn’t. He could code a little, hack a wardrobe license as well as anybody–which was to say, not very well at all–but whatever Julian was doing with confident, sweeping gestures of his hands over the holopad was beyond him.

“House has its own programming language,” Lesa said. “Julian’s been learning to code for it.”

“It uses four‑dimensional matrices,” Julian said. “You would not believe how tricky.” He looked up, and seemed to realize that Kusanagi‑Jones was still standing behind him, peering over his shoulder with a befuddled expression. “This is going to take awhile,” he said, with a child’s sublime confidence in his field of expertise. “You might as well get something to eat. I won’t have anything done before tomorrow.”

“But what,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, folding his hands together to keep his fingers from tightening, “are you doing?”

“Kii’s a computer program, right?” Lesa said. “I mean, he’s Transcendent. He’s a machine intelligence. So theoretically you could rewrite him–”

“A virus,” Vincent said.

“A worm,” Julian corrected. “Or more like…like…repurposing the worm he wrote for Miss Kusanagi‑Jones.”

“Call me Angelo,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, unable to contemplate the specter of this infant calling him Miss anything. A week was overtime on this planet. Ten days was beyond the call of duty.

Julian glanced sideways enough to grin. “Anyway, we’ve got a worm. I just have to, you know, tweak it.”

“It’s not Kii,” Kusanagi‑Jones said reluctantly. It was such an arrogant, audacious plan. Exactly the sort of thing Vincent would come up with, really.

He hated to punch holes in it.

“What do you mean?” Lesa asked. She had sat back down on the bed, and Kusanagi‑Jones was glad. He’d seenher feet, even if she was determined not to show the pain.

And Vincent was looking at him, too. When he’d rather hoped that Vincent would pick up the thread and do the explaining. “It’s the Consent,” Kusanagi‑Jones said. “Not a hive mind, really. But the community makes up its mind and Kii does what the Consent decides. Democracy by decree. Everybody votes, and whatever gets voted up retroactively becomes everybody’s idea. Biochemical. So when Kii says it’s not his decision, he’s not saying anything more than the truth.”

And anyway, he didn’t care how good the New Amazonians were at programming for their adopted domicile, he didn’t believe for a second that the child could actually hack a Transcendent brain. And he didn’t think any of them wanted to live with the consequences of failure.

Lesa stared at him, eyebrows crawling under streaked hair, and then folded her hands over her lap. “Biochemical.”

“Yes.”

“Except it can’t very well be biochemical if he doesn’t have any damned biology, can it?”

“A programmed approximation of biology,” Vincent said. “The important part is he’s not an individual once the decisions have been made. He’s a happy cog, a bit of the machine.”

Lesa nodded slowly. And then she looked at Julian. “So what do you think he’d do if we cut him off from the Consent? Isolated him? Let him…make up his own mind?”

This time, it was Vincent’s gaze on the back of his head that turned Kusanagi‑Jones around. They traded a look, and Vincent slowly shook his head. “I get the impression he’s been edging up to the limits of his authority to help us. Julian, do you think you can do that?”

Julian shrugged. Lesa drew one foot up onto the bed, wincing. She cleared her throat. “I toldyou he was a genius.”

Julian, head bent over the terminal, snorted. “Mom. Please.”

Kii listens.

The bipeds plot. Clever, delicious bipeds, random and amusing. They are eager for change, ravenous for it, the antithesis of the Consent. The Consent are firm in their judgment, unambiguous, and Kii is in agreement. It is too dangerous to become involved with such a chaotic species, one prone to generating and collapsing wave‑states with mad abandon. The wave‑states that originate in the possibility of the Consent intervening on behalf of the bipeds are unpredictable, and some of them endanger the Consent itself.

The possibilities that stem from noninvolvement are safer. Predictable. There is a war, and the defense of the local population of bipeds, those that the khir are fond of.

Most of the others do not survive.

Kaiwo Maru remains a nexus. Where she enters the local system, the potentialities propagate. Where she leaves, they collapse. One choice is safety. The other–

–unpredictable.

There is no intervention. That is the Consent. The ac tions of the Governors and the Coalition Cabinet follow predictions to a nicety. Kii is one with the Consent in this.

But Julian’s involvement is an emerging pattern, one not forecast. It is a new wave. And Kii is not reporting yet, for Kii has neither instruction nor Consent.

Kii is fond of the bipeds. Kii is explorer‑caste. Kii is alien to the Consent in many ways, a valuable, diverse voice in the chorus of similar voices, an evolved risk taker, an outside perspective that exists to be heard and then ignored.

Kii does not resent this. Kii is in agreement with the Consent. Kii will always be one with the Consent.

But the bipeds are so interesting when they’re plotting. And Kii knows that the Consent will be to prevent their plots from coming to fruition. And once the Consent is reached, Kii will be in agreement of it. Will always have been in agreement with it.

Kii will report it when the plotting ceases to be interesting. But Kii is explorer‑caste.

Kii wants to listen first.

They slept while Julian was working. It didn’t matter that it was bright afternoon, hours before siesta and the rains not even a hint of darkness on the horizon; Lesa dropped off midsentence, slumped on her bed with her feet propped on pillows, and when Vincent turned to share a grin with Michelangelo, he found his partner leaned against the wall with his head tipped back and his eyelids fluttering, hands palm‑up on his thighs.

Just as well, Vincent thought. He was in the best shape of any of them, and he was running on ninety‑odd hours of chemistry and snatches of sleep. He told Julian to wake him if anything interesting happened, sat down next to Michelangelo and made a pillow of his shoulder, and was asleep too fast to realize exactly how uncomfortable the position actually was.

He noticed it waking, however.

It was dark in Lesa’s bedroom, the image of the nebula overhead banished as surely as the jungles of the walls. But there was light from the door to the balcony, and Vincent could make out Julian’s silhouette crouched beside him. Any lingering grogginess fled before the lancing pain when he lifted his head. “How long have I been asleep?”

“It’s almost morning,” Julian said. “Agnes came at supper time, but she said not to wake you. The household’s in bed.”

Michelangelo stirred against Vincent’s shoulder, lifting his head and wincing, too. “Done?”

Trust Angelo to cut to the heart. “I’m not sure,” Julian said. “I might be. I’m as done as I know how–”

“Right,” Vincent said. He checked his watch: two hours before sunrise. He’d slept across twenty‑one hours and felt like he could use another eight. Lying flat, preferably; his neck was not forgiving of an evening spent slumped against his partner and the wall.

He scrubbed crusts from his eyes and reached over to push Michelangelo’s sleeve up, checking the status lights on his watch. They burned amber and green, and in their reflected light Angelo’s lips twitched. “Aw.”

Vincent kicked Angelo’s ankle. “Let’s wake your mom up, Julian, and see if we can make your plan happen.”

Even if they had been inclined to skip eating, someone must have requested that House alert the kitchen when Lesa rose, for by the time she’d emerged from the fresher with a towel wrapped around her head, Alys had arrived at the door toting a tray of coffee, toast, fruit, and preserves, along with an assortment of less appetizing things. House produced a small table and four chairs for their use and then Alys had left them alone with their breakfast.

It wouldn’t have occurred to Vincent to feel guilty for the hour if Michelangelo hadn’t mentioned it, but despite that momentary pang of conscience his stomach thanked him for the care and the coffee–which they must grow locally, the way they went through the stuff. On Ur, it was an expensive, imported treat, but Ur was notably lacking the sort of tropical climates in which the plants thrived. In Penthesilea, you could probably grow them on rooftops, if the city had permitted it.

Of course, on Ur, a potentially invasive alien plant would never be legally cultivated, though Vincent knew there were black‑market greenhouses. It marked another way in which New Amazonia’s government was environmentally permissive.

Vincent, watching Lesa nurse her third cup of coffee while Angelo took his turn in the shower, noticed that she wasn’t wearing her honor, and tried not to think that today was the day of the duel.

Lesa’d dressed in a skirt and a tunic and freshened her bandages, and though she still hobbled on crutches, Vincent thought her feet and ankles looked less swollen. He could make out the outline of bones and muscle under the tightly wrapped gauze, anyway, which he couldn’t have done yesterday.

She seemed calm as she watched Julian pack food away, and not at all like a woman contemplating a Dragon. Or a duel.

The human animal’s ability to acclimate to nearly anything hadn’t ceased to amaze Vincent. And confound him a little, he thought, as he poured another cup of coffee for himself. The flavor was bitter, satisfyingly rich and full‑bodied, and he cupped both hands around the cup and hooked one heel over the seat of his chair so he could rest his elbow on his knee.

Michelangelo, clean and steaming faintly, his wardrobe arranged in a plain royal blue shirt and black trousers, came padding out of the fresher and kissed Vincent on the top of the head in a shocking display of affection. He still walked gingerly, his feet dotted with blood blisters and raw places, but even those looked better since yesterday.

There was a kind of pleasing domesticity to this little scene–woman, child, khir catching tossed scraps of toast, uncharacteristically pleasant Michelangelo–and it amused Vincent when he caught himself thinking so. This was nice,the dim room lit by the glow of Julian’s coding display and the gray‑gold sky outside, stained along the rooftops with a peach hue that echoed the color of the tatter‑patterns on Kii’s wing leather. It was a taste of something he’d left behind on Ur, lazy rest‑day mornings with his sisters and brother and mother and both of her husbands sprawled about the atrium, quoting news stories and satire to each other. And it pained him to think of this, and that, arrayed in frail defiance against the machines of the Coalition.

He and Angelo ranked as subtleweapons.

When he looked up from the broken rainbows scattered across the oily surface of his coffee, Lesa was frowning at him. “You’re thinking about what happens if this doesn’t work.”

He shrugged. She probably knew what he was thinking as well as he did. “If it doesn’t work, we fight.”

“Assuming I beat Claude today.” She glanced guiltily at Julian–who was hunched over the terminal, getting toast crumbs in the interface–and then looked down at her hands, both curled clumsily around her coffee mug, and frowned. When she set the mug down and turned her hands up to examine the palms, the fingers stayed curled, and Vincent could see how the heat had puffed and softened her wounds, which were glossy and slick looking where she’d showered the scabs away.

Michelangelo was full of surprises this morning. He crossed behind Vincent, trailing his fingers across his shoulder, and took the four steps to crouch down next to Lesa’s chair with something like his old grace. And then he reached out gingerly and slid thick fingers around her wrist, drawing her hand out and turning it over so he could brush a kiss across the back. Old Earth chivalry.