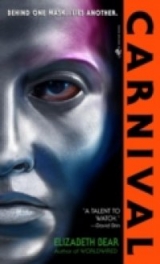

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

A glossy exterior that showed only the reflection of the person looking in.

Except for now, when Michelangelo lifted himself, asking, and Vincent came to him. Exertion stung the tender skin on Vincent’s back and buttocks and sweat dripped into his eyes, scattering over Michelangelo’s shoulders as Angelo stretched under him. Vincent’s wardrobe was overloading again; he didn’t care. Headfucks and Venus flytraps and feedback loops were all right, but they didn’t satisfy the inner animal the way good, old‑fashioned, biological sexdid. Heart rate, brain chemistry, blood pressure–it all benefited from this: competition, cooperation, intercourse. Conversation, as much game as release.

He rocked against Angelo, hands and mouth busy on whatever he could reach. Michelangelo answered him with sounds that might have indicated pain, if they hadn’t come in tandem with the eager motions of his hips and the clench of his hands in the bedclothes. Michelangelo flexed to meet his final, savage demands, and then they slumped together and pooled, relaxing.

Everything’s better with a friend,Vincent thought, snorting with laughter.

“Glad to know I amuse you,” replied the dryly muffled voice, Michelangelo slipping into their code.

Vincent resettled against his back, racing heartbeats synchronizing. “What did that Ouagadougou woman want with you?”

“You caught that?” Angelo sounded sleepy. “One of ours.”

“Coalition?”

“Mmm. Our contact. Slipped me a map this afternoon. Might do some exploring in a bit.”

“Alone?”

“Easier to countermeasure one than two, and I spent more time in the gallery than you did.”

“What’s the gallery got to do with anything?”

“Seems to be how you get there, if I’m reading this thing right–” Shoulders already whisked dry by utility fogs rose and fell against Vincent’s chest. “What’d you find out?”

Vincent thought of the unexamined chip concealed under the table edge, and dropped his chin on Angelo’s shoulder. “House–The city, I mean. Lesa called it House.”

“Yeah?”

“I think it’s an AI. Not sure if it’s sentient–I mean, self‑aware–or not, but it’s sure as hell sapient. It problem‑solves. And works from limited data to provide a best‑response.”

“Tells us how the marines died.”

“Sure. The city just…lured them where the Elders wanted them brought. And then walled them up. For as long as it took.”

That brought a long silence, and then a sigh. “Hope the countermeasures work.”

Vincent grunted. Michelangelo stretched again, the restless motion of hips and shoulders that meant get off me, oaf.

Vincent rolled clear. “How will you bypass security?”

“Don’t be silly,” said Angelo. “Going to turn invisible.”

Lesa made sure Agnes knew she wouldn’t be expecting Robert that night. She sat before her mirror, combing the brighteners into her hair, and contemplated the blankness with which Vincent had met her code phrase. A code phrase encoded on the chip he’dprovided, at the meet prearranged by Katherine Lexasdaughter.

Which Robert had taken directly from his hand, palmed, and pressed immediately into hers. Vincent didn’t know who he was to meet on New Amazonia. Couldn’t know, before he made planetfall. It was too dangerous for everyone concerned.

Which was why the elaborate system of double blinds and duplicity. Isolation. Containment. Any good conspiracy needs fire doors. Lesa had required a chance to assess Katherinessen before she–and more important Elena–revealed herself. But when she’d tried to make the final connection…

Robert had palmed the chip and handed it directly to her.

Lesa’s comb stopped in her hair. Robert had also been left alone with Vincent for at least half an hour before Lesa attempted to seal the contact.

She untangled the comb carefully, reversed its field with a touch on the controls, and redacted the brighteners. When her hair was clean, she folded the comb into its slot in the wall and stood. She stepped over Walter to reach the house com on the wall by the door. “House, please contact Agnes.”

A moment later, Agnes answered, and Lesa told her that under no circumstances was Robert to leave the Blue Rooms. Agnes wanted details, and Lesa was forced to admit she had none to offer, “–but trust me on this.”

She was already pulling on her boots as she said it. When House ended the connection, she called through the fabric of a thin black mock‑neck for a car. She strapped on her honor, pulled her hair back into a plain tail, and hit the door at a trot.

The car was waiting at the end of the alley. There were some perks to being a government employee.

There were days when Kusanagi‑Jones wished he were better at lying to himself, and then there were the days when he was pretty sure he had it down to a science. While Vincent made idle conversation, he split his wardrobe under the covers of the bed they had made love in, left the remainder to assemble a warm, breathing, nanometer‑thick shell, and set what he retained to camouflage mode. When he stood up, as promised, he was invisible.

Well, not trulyinvisible. But his wardrobe handled minor issues like refracting light around him through the same process by which it could provide a 360‑degree prospect in a combat situation, a lensing effect. It contained his body heat, presenting an ambient‑temperature surface to any thermal imaging devices, and it filtered carbon and other emissions.

The drawback was that it would get hot and stuffy in there rather quickly. He would have to move fast.

Kusanagi‑Jones stood against the wall beside the door as Vincent opened it and called Cathay inside on the excuse of wanting a late snack. She came, yawning, and Kusanagi‑Jones slipped past her before the door could iris shut.

The second security agent outside wasn’t Shafaqat. They must be trading off. In any case, she was standing against the wall, admirably placed to see anyone coming in either direction down the short curved hall, but with only a peripheral view of the door at her back. Kusanagi‑Jones slipped past in complete silence, the only clue to his passage the dimpling of the carpetplant underfoot. She didn’t notice.

The lift was a challenge, but it was out of sight around the curve of the hall. He spoke softly and the door glided open. He stepped inside. He wanted to breathe deeply, to savor feeling alive in his skin and the lingering tenderness of sex. But he kept his breaths short and slow, giving his wardrobe as much help as he could. He couldn’t afford to dwell on pleasant memories when he was here to fail the man who created them.

Vincent waited until Cathay returned with a tray, toast and tea for two. He thanked her, then cleared Angelo’s solar collector from the edge of the open window. He sat on the ledge to eat the toast and drink the tea. Then he climbed back into bed beside the homunculus and repeated Angelo’s trick of mitosis. When he stood, he collected the unviewed chip from its hiding place and slotted it into his reader. The chip contained a map. He studied it while leaning out the window, examining the teeming city below.

Then he put one foot up and rose into the frame.

Anyone in the room would have registered nothing. No movement, no shifting of the light except a faint sparkle of mismatched edges if they had happened to look at the window just as he stepped up into it.

It was a long way down. Vincent let go of the window frame, lifted his arms, and stepped out.

Unlike a parachute, there was no shock as his wardrobe unfurled, growing filaments and tendrils festooned with catch pockets. The air resistance slowed him before he could build up falling velocity. He ballooned down like a spider, steering for a smooth dimple at the base of the tower, and landed squarely where he’d aimed. But faster than he should have; he rolled with it, but his knee twinged, and his wardrobe couldn’t quite absorb the shock enough to protect his sun‑seared shoulder. He whimpered when he hit, but the street noise was enough to cover that. In camouflage mode, his wardrobe would damp most of the noise anyway.

Once the wardrobe contracted, he slithered down the curved roofline to drop to street level, earning another twinge from his knee. He checked the map; the meeting place was one square over, in the open. No proof against listening devices, but if his suspicions were right, a member of security directorate would be making sure no records remained.

He slipped through the crowds into darkness, following the map through quieter streets. There were only a few reeling revelers here, and he avoided them easily. Somewhere in the distance, he heard fireworks or gunfire.

He fully expected that the shadow awaiting him in the darkness under an arched walkway would be Lesa Pretoria. He hadn’t been sure until that evening, but the complex of her kinetics over dinner had convinced him, though she’d never dropped a recognition code. He paused in shadows to cancel the camouflage, dressed in local fashion and mocked up something that would pass from a distance for a street license with a quick accessory program–he didn’t have a license for a hat, but he had one for a wrist cuff–and presented himself boldly alongside the arch, circumnavigating merrymakers as he went, restraining the urge to press his hand to his aching shoulder. The pain was nauseating.

He was drawing a breath to greet Miss Pretoria when an entirely different voice interrupted him, and a woman older and stouter than Lesa stepped into the light. “Miss Katherinessen,” she said. “I’m pleased you could get away.”

“Elder Kyoto,” he choked. “This is a surprise.”

Once Kusanagi‑Jones reached street level and slipped into the night, he moved faster. The unrippled pavement was sun‑warm under his feet, and he had little trouble winding through the scattered revelers by Gorgon‑light. The gallery lay across the square. Penthesilea’s government center was compact, and it wasn’t the center of the party. Kusanagi‑Jones only had to cope with the overflow.

He heard music from elsewhere in the city, cheers and laughter that suggested a parade or theatrical event. He triggered the full‑circle display, the fisheye appearing in the lower corner of his sight where peripheral vision would pick it up. Years of training meant he’d react to it as fast as to a flicker in the corner of his eye, and as accurately.

He passed between drunks and singers, hesitated at the report of gunfire and an echoing siren. Four shots, but they were distant and spaced like a duel, and though heads turned, nobody reacted more strongly. He crept around to the back of the gallery, to the broad doors where more trucks of repatriated art were being unloaded and the protectively wrapped bundles carted in, to be hung in accordance with the afternoon’s plan.

He skulked inside.

The lifts were running regularly. He simply stepped into an empty one, rode it down, ducked around a group of incoming laborers–mostly licensed men, and two armed women–and found himself at liberty in the gallery space.

The instructions Miss Ouagadougou had provided were quite precise. He crossed the first gallery and ascended the stair under the watchful eyes of the frieze. When he reached the far corner, he paused. This adventure would have been considerably less nerve‑wracking if there were some mechanical means of opening the passage, something that could be hacked or bypassed.

If Vincent was right, there was a machine intelligence watching him. And Kusanagi‑Jones could only hope its instructions didn’t include the casual destruction of off‑world human males poking about where they shouldn’t be.

It wasn’t as long a gamble as it seemed. He had, at best, speculation that the city might take action if it construed a major threat to its inhabitants–such as a ships’ complement of Coalition marines. But Penthesilea remained an alien artifact, and if it could be efficiently reprogrammed or trained, he had no hope of carrying out his mission. And yet, here he was, against reason and sanity, doing what he did in the hope it didn’t have protocols in place to deal with saboteurs and spies.

It was the old ambiguity that set his heart racing and dumped adrenaline into his bloodstream. Nobody sane would be here. But then, nobody sane would have taken this job in the first place. Especially when the most likely scenario, in the wake of the afternoon’s attempt on Vincent, had Miss Ouagadougou luring him to a lonely place where he could be abducted or disappeared.

He lowered the audio damping, checked the fisheye display to make sure the gallery floor was clear, and asked House, please, to open the wall.

Before he finished speaking, the frieze before him parted like drawn curtains. He stepped forward into an arched tunnel, unsurprised when the opening sealed itself behind him. An indirect glow rendered his light amplification redundant; he dialed it down, but in deference to his mistrust of Miss Ouagadougou he left the camouflage protocol intact.

The tunnel was undecorated, smooth sided, the walls velvety and dark. It tended downward, the walls corded with shielded cables. Lesser ran into greater to form a vast, inverted mechanical root system, which thickened toward a trunk as he descended. The overall effect was Gigeresque, though the textures were more reminiscent of Leighton’s velvets and silks.

He breathed easier. It was an access tunnel. Which meant, at least potentially, that Miss Ouagadougou had sent him to the right place. “Thank you,” he said, feeling slightly foolish. The city didn’t answer, but neither did the ongoing sense of observation (like a pressure between his shoulder blades) ease. He snorted softly when he realized he had expected it to, and kept walking.

Brightness spilled up the corridor as it leveled. He paused to let his eyes adapt. His wardrobe handled dazzle, but didn’t ensure fine perception.

Fifteen seconds sufficed. He blinked once more, to be sure, and stepped forward into a chamber not much larger than the suite he shared with Vincent. It was bowl shaped, the walls arching to meet overhead in a smooth, steep‑sided dome. He knew he was underground, but the depth of field in the images surrounding him was breathtaking. They were not just projected into the walls, but a full holographic display.

If it weren’t for the tug of gravity on his boots, he might have been adrift in space. New Amazonia’s primary, Kali, glowed enormous and bittersweet orange on his left hand, smeared behind watercolor veils. On his right, totally out of perspective, floated New Amazonia, a cloud‑marbled berry with insignificant ice caps, incrementally closer to its primary than Earth was to Sol, partially shielded from Kali’s greater energy output by the Gorgon’s polychrome embrace.

The fisheye showed him stars on every side. He turned toward the sun. And a peculiar thing happened. The nebula dimmed, parted along his line of sight, and left him staring at the filtered image of Kali. He knew it was filtered, because his wardrobe wasn’t blinking override warnings about staring into it, and everything around it didn’t flicker dim as the utility fog struggled to compensate. The bruise‑limned darkness of sunspots hung vivid against the glare, the ceaseless fidgeting of the corona marked abruptly by the dolphin leap of a solar arch. It seemed close enough to reach out his hand and touch, enormous, though his palm at full extension eclipsed the sphere.

Teeth rolling his lower lip, Kusanagi‑Jones returned to New Amazonia. The veils swept back from it as well, focus tightening, and as the holographic point of view swept in, he found himself retracing the rough course of the lighter that had brought him to this planet. He circled Penthesilea, and there the image hesitated. Waiting, he realized. Hovering like a butterfly on trembling wingbeats, accommodating the wind.

“House, show me the power generation system, please.”

The image swooped again. A flying creature’s preferred perspective, as internal decor mimicking wide open spaces and empty skies would be comforting to a creature with wings, where an ape’s descendent might feel cozy with limited perspectives and broken sight lines, the indication of places to hide.

The sense of falling made his fingers flex, trying to clutch a railing that wasn’t there. He mastered himself, despite the sense that there was nothing to stand on as images rushed past incomprehensibly fast. And then they paused, arrested sharply, and he found himself staring at the back of his own head, the wooly curls of a dark man in a star‑spangled room.

His fisheye–and his own eyes–showed him that the image hewatched hadn’t changed. But the room around the virtual Kusanagi‑Jones dissolved, vanished into clear air, leaving him standing at the bottom of a sphere whose every surface writhed with twisted cable. It was a strangely organic growth, fractal in the way it merged and combined, coming together in a massive, downward‑tending trunk beneath Kusanagi‑Jones’s feet.

The hologram had stripped away the chamber’s walls, showing him what lay behind them. His neck chilled. He rubbed his palms against his thighs. “Follow the cables, please.”

The perspective zoomed down– throughhim, and he blinked at the glimpse of meat and bone and wiring and a momentary cross‑section of a pulsing heart–and chased the tunneling cables down, down, to bedrock and a cavern in the depth‑warmed darkness.

He was no electrical engineer. But an encyclopedic education, RAM‑assisted parsing, and the information he’d chipped when he came out of cryo identified most of the machinery. Capacitors, transformers, batteries, a bank of quantum processors big enough to run a starship: essentially, an electrical substation the size of some Earth cities.

And no sign whatsoever of a generator. Just the power endlessly flowing from the quantum array–

Fromthe quantum array.

“Shit,” Kusanagi‑Jones said. He had an excellent memory. He could recall Elder Singapore’s slightly amused tone precisely, as she had said, But you can’t get there from here.“The power source isn’t on this planet.”

A flicker of motion in his fisheye alerted him a split second before an urbane, perfectly modulated voice answered him. He turned, binocular vision better than peripheral, the fisheye snapping down on the sudden motion and giving him a blurred preview that didn’t remotely prepare him.

The head that hung over him was a meter long from occiput to muzzle, paved about the mouth and up to the eyes on either side with beady scales that ranged in color from azure to indigo. Flatter scales plated under the jaw and down the throat, creamy ivory and sunrise‑yellow. A fluff of threadlike feathers began as a peach‑and‑cream crest between the eyes, broadened to a mane on the neck and down the spine, spread across the flanks, and downed the outside of the thighs. The forelimbs, folded tight against the animal’s ribs, raised towering spikes on either side of its shoulders–the outermost fingers of hands that were curled under to support the front half.

Support it couldn’t have needed, because the entire four‑meter‑long animal was lucently transparent. It was a projection.

“You are wrong, esthelichMichelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones. Planetary margins are irrelevant. The cosmocline is not in this brane,” the ghost of a Dragon said, and paused before it continued.

“Good morning, esthelich. Kii greets you. Kii is explorer‑caste. Kii speaks for the Consent.”

BOOK TWO

The Mortification of the Flesh

13

“YOU OPPOSE CONSENT,” KII SAID, THE SPIKED TIPS OF folded wings canting back as it settled onto its haunches, knuckles extended before it like a crouching dog’s paws. Its long neck stretched, dipping slightly at the center as it brought its head to Kusanagi‑Jones’s level. Its phantom tongue flicked out, hovered in the air, tested, considered. “You are disloyal.”

Kusanagi‑Jones had no answer. He was poised, defensively, ready to move, to attack or evade. But there was nothing here he could touch, and the creature’s capabilities were unmeasured.

It paused, though, cocking its head side to side as if to judge distance, and nictitating membranes wiped across wide golden eyes. It seemed to consider. “Perfidious,” it tried, and Kusanagi‑Jones could see that the thing wasn’t actually speaking. The voice was generated stereophonically, so it seemed to originate near Kii’s mouth–if Kii was the animal’s name, and not its species identifier or a personal pronoun or something Kusanagi‑Jones wasn’t even thinking of–but the mouth didn’t work around the words, and its breathing flared and flexed nostrils, uninterrupted. “Treasonous,” it considered, lingering over the flavor of the word, and then shook its head like a bird shaking off water. “Disloyal,” it decided gravely. “You are disloyal.”

Michelangelo found himself quite unintentionally disarmed by this haphazard pedantry, though he fought it. He straightened, breathing slowly, and let his hands fall to his sides. He kept his balance light, weight centered on the balls of his feet. He would move if he had to and try to look calm in the meantime. The preliminary indicators were that Kii was nonaggressive. It might be a sort of…user‑friendly interface bot designed for a Dragon. The alien’s equivalent of an application assistant.

“Request clarification,” Kusanagi‑Jones said.

Kii’s tongue flickered. It settled another notch, lowering itself to its transparent belly, drawing its head back, neck a sinuous curve. The tension in Kusanagi‑Jones’s gut untwisted another notch, the lizard in the back of his skull reacting to a lowering of threat level–as if the Dragon’s appearance of ease mattered at all. Any attack, if it came, need have nothing to do with a hologram; a laser concealed in a wall port would suffice.

“You are a member of a population in competition with the local population,” Kii said. “But your transmissions indicate that your allegiance to your own population is…” It paused again, head rocking and eyes upcast. Kusanagi‑Jones imagined the Dragon was searching for an unfamiliar word again. “–spurious.”

Kusanagi‑Jones licked his lips. It wasn’t technicallya question. More an observation. Maybe he could return a question of his own. “Are you House? Wait, belay that. Are you the intelligence known as House?”

“Kii is…”

Kusanagi‑Jones thought that the approximations occurred when it was searching for a word in New Amazonia’s patois that matched a concept in its own language. He waited it out.

“Kii is not‑House,” it said. “House is House. House is a construct. Kii is of the Consent.”

Not I. Kii.Maybe not a personal pronoun. But it understood them–it used youfluently enough. So there was some reason it didn’t think of itself as I. Or even we,the logical choice if it were a hive‑mind. “Kii is a virtual intelligence?”

“Kii is translated.” It stopped again, nictitating. “Transformed. Molted,” it said, and then, triumphantly, the spiked fingertips flipping up to reveal cream‑and‑ultramarine wing leather in blurred, torn‑paper patterns: “Fledged!”

Kusanagi‑Jones put his hand against his mouth. He pressed it there, and thought. “You’re a transcendent intelligence,” he said. Kii blinked great translucent eyes. “What do you want?”

What he meant was, why haven’t you killed me the way you killed the last Coalition forces to land here?But that seemed an impolitic question. I’m not trained for first contact–

But this wasn’t first contact either. First contact was handled. First contact was more than a hundred Terran years ago. It didn’t matter if the New Amazonians knew that the Dragons still inhabited their cities, after a fashion–which was something that Kusanagi‑Jones wasn’t prepared to assume–because the Dragons definitely knew rather a lot about humans.

“Your population is expansionist,” Kii said, after it had given Kusanagi‑Jones adequate time to consider the stupidity of his blurted question. “But intelligent. Kii wishes to encourage dйtente.” It showed him teeth, back‑curved spikes suitable for holding and shredding meat. “Kii is not eager to repeat, no, reiterate a massacre.”

“I am not eager to be massacred,” Kusanagi‑Jones replied. “You’ve ethics.”

“You have aesthetics,” Kii said. “But no Consent. No true Consent.” It hissed, frustrated. “You act in ways that are not species‑ordained.”

“And you do not?” It was surprisingly easy to relax with the thing. For all its alienness, it made no threatening gestures, did nothing but occasionally tilt its head and twitch the spikes of its wingtips into a more comfortable pose.

“Kii follows Consent,” it said. That ripple of the downy feathers on its neck almost looked like a skin‑shiver. “Consent is…ordained.”

It was watching him. Trying the words in turn and seeing how he reacted. Testing them on him, until something–his body language, his scent–told it he was understanding as it wished.

“I follow my leaders, too.”

Could that be the thing’s answer to a smile? After 150 years of observation, it must comprehend human body language. Especially if it was reading his responses.

But he was a Liar.

“Biochemical,” it explained after another pause.

Oh. Ah. Not a group mind, then, but something closer to a political structure…albeit one enforced by biology. Or programming, in the case of a life form that wasn’t biological anymore. “Consent?”

“Yes.”

“Can’t argue my people out of coming here. They’ll–” Kusanagi‑Jones shrugged and spread his hands out, pale palms up, dark backs inverted. They won’t leave something like you at their flank.A raw frontier world with a powerful bargaining chip, they mightnegotiate with, if the cost of occupation was deemed higher than the benefit gained. But a Transcendent alien species, with no apparent defenses, and the promise of all that energy, all that technology–

The Coalition had proven its acquisitiveness. On Ur, on New Earth–spectacular failure though thathad been–and on half a dozen other worlds. Thiswould be one bastard of an interesting brawl in Cabinet, in any case. It might be worthwhile to send combat fogs into the population centers just on the chance there might be pieces to pick up later.

“If you cannot convince your population to leave Kii’s…pets, Kii’s associates, in possession of these resources,” Kii said, “Kii will kill them. As necessary.”

Lesa had made Cathay and Asha wait in the hall as she passcoded the door to the Coalition agents’ suite and went inside. The simulacra in the bed were effective, but they wouldn’t bear up to a touch. Still, she stood over them, listening to the sound of their breathing–“Vincent’s” a regular hiss, “Michelangelo’s” touched by a faint hint of snore–and closed her eyes.

Robert had end‑run her. And the essential link to Ur and rebellion could be walking into a trap right now–or, worse or better, arranging a deal with a rival faction.

Lesa knew her mother. If Elena wasn’t in charge, Elena was unlikely to play. And if Elena didn’t play–

–Lesa’s own chances of getting Julian off‑planet to Ur, if he didn’t prove gentle, went from reasonable to infinitesimal.

Ignoring the monitors (she’d be the one who examined the recordings), she tugged the covers up slightly, as if tucking in a couple of sleeping spies, and padded back toward the door. It opened and she passed between Asha and Cathay without a word.

“Everything all right?” Asha asked, hooking lustrous dark hair behind her ear with a thumb.

“Fine,” Lesa said over her shoulder. “Sleeping the sleep of the just. Make sure they’re up at five hundred for the repatriation ceremony?” She paused and turned long enough to throw Cathay a wink. “I think they wore themselves out.”

The lift brought her down quickly. Her watch buzzed against her wrist; she touched it and tilted her head to her shoulder to block external noise. Her earpiece needed replacing. “Agnes?”

“Lesa, Robert’s not in the rooms,” Agnes said, her high‑pitched voice shivering. The words came crisp and clipped, as if she’d had them all lined up, ready to rush forward as soon as her mouth was opened. “Do you want a constable on it?”

Lesa’s mouth filled with bitter acid. “Does Mother know?”

Agnes paused. “I called you before I woke her.” Which was a violation of protocol. But Lesa would have done the same.

There were any number of possibilities, but only two seemed likely. Robert was a double. Which meant he was working for either a free male faction, like Parity or–she prayed not–Right Hand Path. Or he was working for security directorate, and she’d just bought herself a sunrise execution.

“You did the right thing,” Lesa said. As she walked out into Government Center she passed the community car she’d taken here, which was parked silently at the curb waiting for its next call. She paused, frowned at her watch, and then continued, “And send me Walter, would you?”

She leaned a hip and shoulder against the wall as she waited, closing her eyes to cadge a few moments of dozing. Less than ten minutes later the whuff of hot breath on her hand and the tickle of feathers alerted her. She stroked a palm across Walter’s skull, laying his ear fronds flat and caressing warm down and scales. He panted slightly with the run, but he’d had no trouble finding her. Penthesilea wasn’t a big city in terms of area; he was trained as a package‑runner, and he regularly went on errands with Robert or Katya. Agnes would have just told him find Lesa at work,and once he was at Government Center, he would have traced her scent.

“Good khir,” she said, and gave him her other hand, the one she’d stroked through the Coalition agents’ bedding. He whuffed again and went down on his haunches, not sitting but crouching. He lifted his head, ear‑fronds and crest fluffing, and waited, his eyes glowing dimly with gathered light.

“Find it, please,” Lesa said. Walter nosed her hand again. “No cookie,” she said, shaking her head. She had nothing to bribe him with. “Find.”

He whuffed one last time, disappointed, and bounced up into an ambling trot, nose to the ground. She waited while he cast back and forth, darting one way and then the other, feathery whiskers sweeping the square. They framed the end of his mouth like a Van Dyke, above and below the labial pits, and served a dual purpose–as sensitive instruments of touch and for stirring up, gathering, and concentrating aromas.