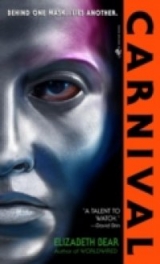

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

She might even be right.

In any case, if Vincent was likely to wind up smuggling the kid home in his suitcase, he might as well get to know him. “I am, among other things. Your mother’s very proud of you.”

The child sidled along the wall sideways, back to the house but meeting Vincent’s eyes defiantly. “She says if I want to be a mathematician I have to be like you.”

“Like me?”

Julian nodded, his hands linking behind him, shoulders squeezing back as he crowded against the wall. “Gentle. Otherwise I’ll be sent to foster and train soon, and then I’ll go to the Trials and be chosen by another house.”

“And you won’t have time for mathematics then?” As Vincent understood it, not everybody was as…permissive…with their stud males as Pretoria house. His heart skipped painfully while he waited for the answer. Poor kid.

“Mother says,” Julian said, tilting his head back as he recalled her words, “that women don’t like males who seem too smart. They find them threatening.”

What an elegant little parrot she’s created,Vincent thought, and wanted to bury his face in his hands.

“So she says I can only play with computers and numbers when I grow up if I’m gentle,” Julian continued, still childlike enough to take his silence for rapt attention. “Like you. So I must be gentle…”

“Because you love numbers so much.”

Julian nodded. “But it’s not bad, being like you, right?”

Vincent found the edge of Elena’s wicker chair, sat down on it, and leaned forward with his elbows on his knees. The cosmic irony of the moment didn’t elude him. This child was no more a budding homosexual than Michelangelo was thick‑headed, and Vincent had to fold his hands together to keep them from shaking as he thought about Julian embarking on a life of sexual deception so he’d have an option of careers. “No,” he said. “People can be cruel. But being like me isn’t bad. I had to lie about it for a very long time, though, and pretend to be something I wasn’t to keep my job.”

The boy’s eyes were wide. “I thought you were a diplomat because you’re, you know, because you don’t fight.”

It cost Vincent a painful effort to keep the smile off his face. The last thing this fumbling child needed was to think somebody he was looking to as a role model found him amusing. “Things are different on Old Earth,” he said. “Gentle males are…stigmatized. Do you know that word?”

“The stud males run everything and don’t like gentle ones.”

“Yes.”

“Like the other boys make fun of me for playing with numbers.”

“Yes.”

“How come?” An earnest question, not plaintive, as Julian’s hands fell to his sides as he forgot himself enough to step away from the wall.

It deserved an honest answer. “I don’t know.” Which was as honest as he could be. “Your mother says you’re very talented.”

The boy’s skin was dark, darker than Lesa’s if not as dark as Robert’s. In a better light, Vincent wouldn’t have been able to see him blush. “She said that?”

“She did. She asked me if I would sort of be a mentor for you.” Not too much of a stretch, and Vincent didn’t feel bad about it. The child’s mother and father were missing, his sister was under arrest, and if he felt alone and frightened, he didn’t have to feel thatalone and frightened.

Julian glanced over his shoulder toward the door, the sidelong look of somebody operating under a guilty conscience. “Do you know anything about programming quantum arrays?”

“Not a thing,” Vincent admitted. “But I listen well. You can teach me.”

He set his watch to record, and let the boy chatter on about transforms and quantifiable logic and fractal decision trees and a few thousand other things that might as well have been Swahili. No, not even. Urdu,because thanks to Michelangelo’s remarkable–and habitually concealed–gift for languages, Vincent actually spoke a fair amount of Swahili.

In any case, Julian talked, and Vincent made encouraging noises. And before too long, he started to wonder exactly what Julian was doing wandering around the house alone in the middle of the night, when from what Vincent had seen even young males didn’t go about unescorted. Except, of course, during Carnival.

The boy had to pause for breath eventually. “Julian,” Vincent said, “how did you get out of the Blue Rooms to come talk to me? Did somebody give you a pass?”

Julian’s mobile mouth thinned and he shook his head jerkily. “No pass.”

“So how?”

Because as far as Vincent knew there was supposed to be only one route out of the harem, and it was supposed to be guarded. By Agnes, usually, who had been out of the house trying to locate any trace of Lesa and Michelangelo, and whom Elena had just summoned home to help deal with Katya.

“Did you just walk out?”

“My sire showed me,” Julian said, quietly. “There’s a secret stair. I’m not supposed to tell anybody.”

Which explained how Robert had escaped. “Julian,” Vincent said, “I think you’d better go back before your grandmother catches you out of bed.”

“But–”

“It’s okay. I promise we’ll talk some more tomorrow.” He stood up, slouching enough to minimize his height advantage on a kid who hadn’t hit his growth spurt yet, and came over to Julian, hunkering down a little to speak to him eye to eye. He put his hand on Julian’s shoulder and felt the boy shudder, as if the companionable contact was a threat.

In his society, a sane reaction. “It’s okay,” Vincent said again. “I’ll help. Right now, we have to get your mom back, and my partner. After that–”

Julian nodded jerkily and stepped back into the doorway. They stared at one another for a moment, and then a moment later Julian sidestepped and was gone.

Kii is restless.

This is not a sensation Kii is any longer accustomed to, and Kii is some time in identifying it. Restlessness is not one of the emotional routines that Kii finds useful in Kii’s work.

Kii is somewhat disconcerted at first. Inspection, however, reveals the source of the emotion; it is an outflow of the Consent. The Consent wishes more information regardingKaiwo Maru and regarding the life forms that inhabit her.

They are made things, like the khir, and like the khir, they are guardians. They are intelligent, and they are designed, but they are not people.

There are differences. The khir serve. They guard the Consent’s endless dreamings, but these Governors, while designed to serve a purpose, serve it by ruling over theesthelich creatures who created them.

It is an inversion.

Perhaps the bipeds are truly alien enough to place their destiny in the hands of monsters. Or perhaps there is a miscalculation, and this is the result. Kii cannot yet be sure, and the Consent is chary of deciding on so thin a pattern.

Kii continues to research. The Governors are an advantage to Kii’s bipeds–the local colony, that is. The bipeds Kii identifies as Kii’s pets, and which the Consent is to abet.

The Governors advantage Kii’s bipeds because they severely curtail the growth of the nonlocal population.

But they are a disadvantage as well. They create a population that is extremely creative and active, without the drain of substandard individuals. In other words, by ensuring that only extraordinary and accomplished individuals survive, and by skewing that population toward those most practically creative, the Governors nourish innovation. They force the Coalition outward, groping, grasping, subsuming other colony worlds.

They are the engine that drives the expansion that Kii has informed Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones that Kii will not permit in local space‑time.

The Consent is temporary. The potentialities are complex, the patterns not yet emergent. The current solution is to prepare for three eventualities deemed likely. The first requires no action, as there are possibilities in motion that carry the Coalition away from local space‑time for the foreseeable potentialities. The second is the need to eradicate the Governors as a species, which will alleviate immediate population pressure on the Coalition worlds and thus the immediate threat to the local colony. This solution carries an attendant ecological cost and an eventual pattern that may mean dealing with stronger and larger Coalition feelers. The third is to prepare to exterminate as much of the nonlocal population of bipeds as is deemed necessary to prevent their encroachment, if the emerging pattern proves them belligerent.

When the waves collapse, Kii will be glad to no longer worry. But they are not yet resolved, and so Kiiis worried, and the Consent is not open to Kii’s advice.

Kii believes that a preemptive strike would be more effective.Kaiwo Maru is the nexus of probabilities, the center of the indeterminacies. IfKaiwo Maru is destroyed, so many waves collapse–

Kii is overruled. The Consent is that there are too manyesthelich intelligences aboardKaiwo Maru in addition to the Governors, and theesthelich do not act yet in belligerence. The Consent is to observe and prepare.

The Consent takes hold, and Kii ceases to recall why Kii, in an alternately collapsed wave, would have felt differently.

When Elena returned in the growing light of morning, Vincent’s fisheye showed that she’d been crying. He hadn’t resumed her chair after Julian left, and instead stood in the shadows near the lattice, watching things like moths and probably named for them come and go among the dead, plucked flowers, ignoring what threads of music and laughter drifted in from the streets. They were jangling, frantic sounds. Have fun quick, before someone comes and stops you.

“You don’t like the garland,” Elena said, when he realized she was waiting for him to notice her, and turned. Her voice rasped. She coughed and rubbed her mouth with her hand.

“They’re dead. It strikes me as macabre to hang murdered plants all over your buildings. How much longer is Carnival?”

“Seven days,” she said. “Ten all together. And the flowers are dead because nothing grows in a Dragon city. Except carpetplant. They do their own weeding.”

“I didn’t think of that.”

“That’s how the cities survived intact.” She came closer and joined him at the lattice, peering through the blooms to the empty courtyard. “Katya’s not talking,” she said. “We’re going to have to go to Claude.”

“Not an option,” he said, and bit his lip. “I didn’t mean to say that. Some sneaky, underhanded diplomat I am.”

She didn’t step closer, but he felt her warmth against his arm. It reminded him that his shoulders itched, and he tightened his fingers on the ledge of the porch railing.

“You’re more worried about him than you pretend.”

He looked at her standing there, open‑eyed, empty‑palmed, and for a moment almost managed to think of her as human.

“We need to involve security and the militia,” she continued when it became apparent he had nothing to say. “I can’t do that without Claude.”

“Elder Kyoto is on our side.”

“Elder Kyoto wouldn’t keep her job long enough to be of any use to us if she tried to sneak this past the administration. Why are you so opposed to involving them?”

“Other than her challenging Angelo to a duel?”

“Political maneuvering,” Elena said with a wave of her hand. “There’s more.”

“All right,” Vincent said, and let his hands fall open, too. “I believe she and Saide Austin are aware of–no, in collusion with–the operators of an illegal genetics lab somewhere on New Amazonia. And that they used that lab to create a retrovirus with which they then infected my partner, with the intent of spreading a deadly epidemic across Old Earth.”

“You have proof?” Elena asked, as of course she would.

“It’s in Angelo’s bloodstream,” Vincent answered. “We hadn’t had time to get it taken care of yet.”

“Oh.” She took a half‑step forward, belly against the railing, her hands curled hard on the edge.

“Yeah,” Vincent said. “I’m not sure talking to Claude is the best possible solution.”

“No,” Elena said. “The genetic engineering, though. If we could prove that, we wouldn’t even have to have her killed.”

“So all we have to do is find a genetic lab so well hidden nobody in Penthesilea knows where it is.”

“You’ve never had to find an illegal drug lab?” Elena said. “Somebody always knows. I just wish Lesa were here.”

“Out of danger?”

“To help find it. Security directorate is what she does.”

21

LESA KNEW HER WAY THROUGH THE BUSH. UNARMED, barefoot, injured, and clad in the rags of city clothes, she managed to stay ahead of the pursuit for almost twelve hours, through the afternoon rain and well into the evening of the long New Amazonian day, until the sounds of voices faded and the only man‑made sound she heard was the occasional distant, echoing signal by gunfire, followed by a crescendo of animal complaint.

She regretted not having a bush knife most of all. A gun would have been nice, and it chafed not to have her honor at her hip, but a knife would have made travel infinitely easier. It also would have left a defined trail, of course, but crawling under still more thorny wire‑plant, her scratched hands and forearms swelling with infection, she didn’t think she’d care. At least the tender redness was likely just her own skin flora; most New Amazonian bacteria didn’t like the taste of Earth meat any better than did the New Amazonian bugs.

Once the sun was up, she had managed a good bearing, though that wasn’t much use without a reference point. Then, for lack of options, she had headed east. If the Right Hand hadn’t brought her too far from Penthesilea, she’d find a coast in that direction. And if they’d transported her any distance–well, this looked like home jungle, and if it wasn’t, something was very likely to eat her before she starved.

Unlike the “insects” and the “bacteria,” some of the larger New Amazonian life had absolutely no objection to the taste of mammal. And fexa were quite territorial.

In any case, it was bound to be a long walk.

At least she could entertain herself as she picked her way over borer‑addled trunks and through drapes of waterlogged vines by trying to decide how she was going to explain to Vincent that she’d left Kusanagi‑Jones behind.

The conscious edge of her brain wasn’t helping her anyway. What she needed was the inner animal, the instincts tuned to shifts of light and the cries of big‑eyed, ringtailed treekats awakening for the night and the black‑and‑violet, four‑winged Francisco’s macaws settling down in their roosts. She thought about fashioning weapons, but that would take time, and her advantage right now was in staying ahead of her pursuers–well‑armed men who knew the lay of the land.

She did pick up a stout branch, green and springy. It had a gnawed, pointed gnarl at the base where it had been disarticulated by a treekat after the infestation of bugs in the heartwood. The smaller twigs had withered since it fell, but only a few rootlets protruded; she stripped them away, broke the slender end off, and found herself possessed of a serviceable three‑foot‑long club.

The rich scent of loam rose from under her denting footsteps, and insectoids scurried from overturned litter. She made an effort to walk more lightly, picking past clumps of moss that would show her footsteps, hopping between patches of wild carpetplant that flourished where sunlight managed to pierce the canopy in long, flickering rays. It wouldn’t bruise, even when she jumped on it, and it beat sticking to game trails. Those would lead pursuit right to her.

She needed to find a place to bed down for the night.

Lesa had slept rough before, but she had no illusions about her odds of surviving a night in the jungle unarmed, without shelter, and without daring to build a fire even if she had the wherewithal to do so. It might keep off animals, but it would be as good as a beacon to the Right Hand.

At least being dive‑bombed and picked clean by sirens or strangled by a fexa would be quick.

She found a crevice under a fallen log big enough to cram herself into, heaped leaf litter under it to conserve warmth, and hauled a drape of living wire‑plant over the top to serve as a barricade to any wandering animals, savaging her hands further in the process. She picked the thorns out of her palms with her teeth, and dropped them in the cup of a rain‑collecting plant among wriggling tadpoles so the water could help hide the scent of her blood.

The pungent stinging scent of wire‑plant sap would serve to conceal her own body odor.

She crammed herself into her impromptu shelter as dusk was growing thick under the trees, controlled her breathing, and resolutely closed her eyes.

Kusanagi‑Jones sighed and tugged idly at his shackles, galling his wrists and pulling at the shallow knife cut on his forearm. He didn’t shift either the three‑centimeter‑thick staple they were locked to or the beam behind it. Apparently better bondage equipment had arrived during the night. And when he’d been lying on the ground in the center of camp, flat on his back from the paralytic agent the insurgents had used to bring him down, he’d seen several more good‑sized shelters all overhung with holographic and utility fog camouflage. At least two aircars had gone out after Lesa. The entire camp was under a false rain‑forest canopy, all but invisible from the air, probably protected by IR and other countermeasures.

Coalition technology. Which also explained how they’d managed to shut down his wardrobe. Miss Ouagadougou wasn’t the only Coalition agent on the ground here.

Somebody was running guns.

And the nasty, suspicious part of Kusanagi‑Jones’s mind–the one that tended to keep him alive in situations like this–chipped in with the observation that he and Vincent hadn’t been trusted with the information. Which told him that they weren’t the primary operation in this theater.

They were the stalking horse. And the real operation was an armed insurrection.

Who’d miss a couple of disgraced old faggots anyway? And if Vincent happened to get himself killed in theater by enemy action, it wasn’t as if Katherine Lexasdaughter could complain, no matter how much pull she had with the Coalition Cabinet. Which made sense of yesterday’s unutterably stupid grab for Vincent in Penthesilea, too. It gave the Coalition one more big black check mark in the invade New Amazoniacolumn to present the Governors.

At least he was more comfortable now. They’d permitted him access to a privy, and the shackles gave him enough slack to stand, sit, or even stretch out on his back if he crossed his arms over his chest–and enough slack to kick the “food” they’d brought him almost far enough away that he didn’t have to smell charred flesh every time he turned his head.

The water, he’d drunk; it was clean, and there had been plenty of it, and if they wanted to drug him they didn’t need to hide it in his rations when another dart would work just fine. He had tried a few bites of the bread, but there was something cloying about the taste and texture that made him suspect it contained some ingredient he didn’t care to consume.

He’d wait. He wasn’t hungry enough for it to affect his performance, yet.

It was best that Lesa had escaped. She had a better chance of getting back than he did, and a better chance of being heard when she did so. And Kusanagi‑Jones was safer in captivity anyway. Less likely to be raped or tortured–and they hadn’t tried anything yet, though he wouldn’t bet his ration number on it–and more likely to survive the experience if they wanted to use him to extract something from Vincent.

He wouldn’t be held as a bargaining chip, though. Not if they were already receiving Coalition aid. Presuming they knew who they were receiving it from. Which was presuming a lot.

He shifted again, wishing he could rub the torn skin under his manacles or his cut shoulder. His docs weren’t dependent on the power supply of his watch or his wardrobe; they used the kinetic energy of his own bloodstream to power themselves, a failsafe that kept them operational as long as his heart was beating. And they were doing an acceptable job of preventing infection, and even speeding healing, but the wounds could hardly have itched more.

Another damned irritation, like the hunger and the dehydration making him light‑headed in the heat.

He closed his eyes, leaned his head back against the post, and tried to think as Vincent would. What purpose would holding him serve? What was he doing alive?

There was the obvious answer. Bait.

“You know,” Kusanagi‑Jones said to the air, “he really only brings me along so they’ll have someone to take hostage.”

He was bait. A hook in Vincent. Because the Right Hand had missed Vincent, and the Right Hand was taking aid from the OECC. And if anything happened to Vincent, while Katherine Lexasdaughter couldn’t very well take the OECC to task for it, she could certainly demand some kind of retaliation against New Amazonia for so carelessly disposing of her son. And if she didn’t, the Coalition could.

Vincent’s abduction and death was probably a good enough excuse that the Governors would allow the OECC to go to war against New Amazonia. And if anybody in the Cabinet suspected that the recalcitrant leader of the Captain’s Council on Ur was plotting with a bunch of hysterical and heavily armed Amazons, the death of Katherine’s son at the hands of such might be seen as a good enough way of putting an end to any revolutionary alliances.

And wasn’t it just a damned shame that Lesa had already left, and Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t have any way of transferring that particular startling deduction to Vincent.

He could reconstruct the scenario easily enough. Lesa had followed Katya, caught her about to join Stefan and the rest of the revolutionaries, and Katya’s controller had taken Katya “hostage” with a weapon they both knew was loaded with stun capsules, but which Lesa would think lethal. After Kusanagi‑Jones rode to the rescue, Katya had had the presence of mind to establish herself on the winning team by incapacitating her colleagues…until Kusanagi‑Jones let his guard down long enough to get shot in the back like a rookie. And the Right Hand had seen a chance to reset its trap for Vincent.

Kusanagi‑Jones closed his eyes again, settled his shoulders against the unfinished wood of the beam, and tried to ignore the pain in his shoulder enough to nap. It looked like he’d be wanting to escape after all.

He dozed intermittently through the heat of the afternoon. His disabled wardrobe dragged at his body and trapped the heat against his skin, raising irritated bumps, but the docs were working well enough to seal his wound. Occasional shadows across the gap under the door told him when he was observed, and the sweat rolled across his forehead and down his neck to sting his eyes and his cuts.

He didn’t think they’d unsecure him after dark, and was surprised when, as the light was failing, the chain around the doorpost finally rattled and slid. A moment later, the door cracked open and a big silhouette filled the frame.

The door shut behind it and Kusanagi‑Jones heard the chain refastened by someone outside.

“Michelangelo,” the man said, as Kusanagi‑Jones was still blinking his eyes to refocus them after the light. “I am truly sorry about this.”

It was Robert. As he approached, Kusanagi‑Jones pushed himself up the post, determined to meet him standing.

He found the apology somewhat specious, but this didn’t seem the time to explain. So he grunted, and considered for a moment how best to absorb the injury if it came to blows.

But instead, Robert crouched just out of range of Kusanagi‑Jones’s feet and began pulling things from the capacious pockets of his vest. He laid them on the floor, bulbs of some cloudy yellowish fluid and three pieces of unfamiliar fruit. One was knobby and purple‑black in the dim light, the other two larger and creamy yellow, covered in bumps that reminded Kusanagi‑Jones unpleasantly of his current case of prickly heat.

“I brought something you can eat,” Robert said, without rising. His shiny black boots creased across the toes as he balanced lightly, the insteps and toes daubed with clotted mud. Bloused trousers were tucked into the tops just below the knees. His head jerked dismissively at the flat leaf Kusanagi‑Jones had shoved as far away as he could. “I didn’t expect they would have taken any care about it.”

Robert edged the offering forward, while Kusanagi‑Jones watched, feet planted and chained hands hanging at his sides. He kept his eyes on those creases across the toes of Robert’s boots, and not on the hands, or on the food. Or, most important after the endless heat, the liquid.

“What’s in the bulbs?” he asked when Robert had pushed them as close as he meant to and settled back on his heels.

“Dilute bitterfruit. Electrolytes, sugars, and water. Factory sealed, don’t worry.”

“Can’t exactly pick it up,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, moving his hands enough to make the shackles clank.

Robert folded his arms over his knees and looked up, mouth quirking, the faint light catching on the scars that marked his shaven scalp. “Don’t you know how to juggle? Use your feet.”

Kusanagi‑Jones sighed. But he knew how to juggle.

He leaned against the pole, angled one leg out and braced it beside the offerings, and used the ball of the other one to roll the first bulb onto the top of his toes. Then he planted the second foot, shifted his weight, and used the first to flip the bulb into his hands.

Robert applauded lightly, so Kusanagi‑Jones lifted an eyebrow at him and angled his body from the waist, a bow amid clanking. Then he raised his hands to his mouth, the cool, sweating bulb turning the filth on his palms into mud. He tore through the stem with his teeth.

The beverage was an acquired taste. It stung his mouth like tonic water.

It might be nasty, but it cleared his head. He drank slowly, so as not to shock his system, and then retrieved the second globe the same way as the first before he said anything else to the patient, motionless Robert. “So,” he said, weighing the soft‑sided container in his palms, “what price charity?”

“No price.” He hesitated. “If you gave me your promise of good behavior, I could see you moved to better quarters.”

“Don’t pretend concern for my welfare.”

“I am concerned,” Robert said. “We’re freedom fighters, not barbarians. And I’m sorry your arrival here was so rough. It was improvised. They were under instructions not to harm you or Vincent, or Lesa.”

“You make it sound almost as if we’re not bargaining chips.”

Robert smiled, teeth flashing white in the darkness. “You’re almost not. You won’t give me your word?”

And Kusanagi‑Jones opened his mouth to lie–

And could not do it.

He could justify his failure in a dozen ways. The simplest was to tell himself that if he gave Robert his word and broke it, here, now, under these circumstances, he would become useless as an operative in any capacity relating to New Amazonian culture, forever. Their system of honor wouldn’t tolerate it. But it wasn’t that.

“Thanks for the drinks,” he answered, and shook his head.

And Robert grunted and stood, and made a formal sort of bow with folded hands. “Don’t forget your fruit,” he said, and turned to rap on the door, which opened to let him leave.

By the time Kusanagi‑Jones finished the fruit, the hut was as dark as the one he’d woken up in. He dried slick hands on his filthy gi, and then clutched his chains below the shackles, holding tight. Leaning back on his heels, pulling the heavy chain taut, he began to rock back and forth against the staple, trying to limit the pressure on his wounded arm.

Something sniffed Lesa’s lair in the dark of night, the blackness under the shadow of the trees. Whatever it was, it found the wire‑plant discouraging and continued on its way. Lesa slept in fits, too exhausted to stay awake and too overwrought to sleep. She’d never spent a longer night.

In the morning, the cheeping and whirring of alarm calls brought her from a doze as the skies grayed under an encroaching sun. Lesa froze in her paltry shelter, jammed back against the leaf litter that cupped her meager warmth, and held her breath.

There were three of them, two males and a woman. All carried long arms–the woman in addition to the honor at her hip, while the men had bush knives–and one of the males and the woman held them at the ready. The third had his slung and was nodding over a small device in the palm of his hand. They conferred too quietly for Lesa to make out the words, and then the woman leveled her weapon and pointed it at Lesa’s tree. “You might as well come out, Miss Pretoria. Otherwise I’ll just shoot you through the vines, and that would be ignominious.”

Lesa’s cramped limbs trembled as she pried herself from her cave, collecting more long superficial scratches from the wire‑plant as she pushed it aside. She stood hunched, her resting place having done nothing to help the spasm in her neck, and stared at the taller of the two males. His hair was unmistakable, a startling light color that Lesa was almost tempted to call blond, though nobody classically blond had survived Assessment. He was out of context, though, and it took her a moment to place him. The shock of recognition, when it came, was disorienting. Stefan. Stefan, the gentle male who worked as a secretary in the Cultural Directorate. Under Miss Ouagadougou.

Not a direction in which Lesa had been looking for conspiracy.

“Your hands,” the woman said, continuing to cover her while the second male slid his detecting equipment into a cargo pocket and came forth to immobilize her wrists. No cords this time, but ceramic shackles joined by a hinge that allowed only a limited range of motion.

At least he cuffed her hands in front of her and the smooth ceramic didn’t irritate her lacerated wrists. He stepped back three quick steps and grabbed Stefan by the shoulder, turning him away.

The woman didn’t let her rifle waver, and Lesa watched her for several moments, and then sighed and sat down on the mossy log, her bound hands in her lap.

Backs turned or not, she could hear more than they intended her to. And it wasn’t reassuring. Robert’s name was mentioned, followed by a mumble that made the woman snap over her shoulder, “I don’t give a damn what shethinks.”