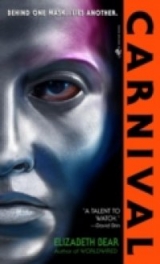

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

“Singapore house,” she said. “I have a dinner invitation.”

He drove carefully, politely, through the rain‑flooded streets. Water peeled away under the groundcar’s tires on long plumes, but the only people outside during cloudover were one or two employed stud males with street licenses hurrying back to their households or dormitories for dinner, and the householders on their porches under umbrella‑covered tables, sipping drinks and enjoying the brief cooling.

The household Claude Singapore shared with her wife, Maiju Montevideo, was on the seaward side of the city, overlooking the broad, smooth bay. By the time Lesa arrived, the clouds had peeled back from the tops of Penthesilea’s storied towers. The rays of the westering sun penetrated, sparking color off the ocean, brightening it from gray to the usual ideal blue.

Lesa Pretoria was not Claude Singapore, and her own rank as a deputy chief of Security Directorate did not entitle her to carry her honor inside another woman’s house. She paused at the top of the steps to Singapore house’s door and surrendered it to the woman who waited there, along with her boots. Both were hung neatly on a rack, and Lesa smiled a thanks. There was a male servant present, too, but he could not touch firearms.

She must come armed, to show her willingness to use her strength in defense of Pretoria household’s alliance with Singapore, and she must be willing to lay that strength aside to meet with Claude. There were forms, and to ignore them was to give offense.

Lesa wasn’t particularly concerned about offending, however prickly Claude might be. Lesa could outduel her. But it was also polite. She gave the male servant her overcoat and followed the woman inside.

Although the rains were barely breaking, Lesa was the last to arrive. Claude and Maiju and the other guests were gathered around a table under a pavilion in the courtyard, sitting on low carpet‑covered stools to keep the dampness off their clothes.

In addition to the prime minister, there was Miss Ouagadougou, the art expert who would be working directly with the Coalition diplomat. She was joined by her male confidential secretary, Stefan–a striking near‑blond, almost unscarred, though Lesa knew he’d had a reputation during his time in the Trials. Beside them sat Lesa’s superior, Elder Kyoto, the head of Security Directorate.

Claude stood as Lesa emerged from the passageway, disentangling her long legs from the bench, and ushered Lesa to a seat–one strategically between Maiju and Stefan, Lesa noticed with a grin. Maiju was separatist; she’d as soon see all the males–stud andgentle–on New Amazonia culled down to the bare minimum and confined to a gulag. Or better yet, the widespread acceptance of reproductive gene splicing.

It would take a revolution to make that happen. Lesa wasn’t the only Penthesilean woman who honestly enjoyed the company–and the physical affection–of males. And artificial insemination and genetic tampering were banned under the New Amazonian constitution. On Old Earth, before the Diaspora, there had been extensive genetic research, and it had led to the birth of people who would be considered abominations in Lesa’s culture. Human clones, genetically manipulated people–their descendents might still be alive on Old Earth today.

One of the representatives the Coalition Cabinet was sending was an Old Earth native. Lesa tried not to think too much about that, about what could be lurking in his ancestry.

Maiju was a radical. But her wife was prime minister, and so she kept her opinions to herself.

“Good evening, Elder Montevideo, Elder Kyoto, Stefan,” Lesa said, as she helped herself to a glossleaf to use as a plate. The dining was informal, and Stefan served her without being asked, graciously playing host.

The dark green leaf curled up at the edges, a convenient lip to pinch her food against. She was hungrier than she had realized, and once Claude resumed her place and began eating, Lesa joined in, rinsing her fingers in the bowl of water by her place to keep them from growing sticky with the sauce. The wine was served in short‑stemmed cups, and she kept her left hand dry for drinking with.

At a more formal meal there would have been utensils, but this was family style, intended to inform those assembled that they might speak freely and conduct business with candor. Nevertheless, Lesa waited until Claude pushed her glossleaf away before she spoke. “Tell me about the delegates,” she said.

“You know the senior diplomat is Vincent Katherinessen, the son of the Captain of Ur.”

“Reclaimed peacefully by the Old Earth Colonial Coalition some fifty‑seven standard years ago,” Lesa said, “and, though there are Governors on‑planet, generally granted unprecedented freedoms by the Cabinet because they keep their own population down, accept Old Earth immigrants, and practice a religion that encourages ecological responsibility. Katherinessen is a superperceiver, which is why he’ll be my especial problem.”

“Yes,” Claude said. “We requested him. He’s the only admitted gentle male in the Coalition’s diplomatic service. There was a scandal–”

“Something on New Earth, wasn’t it?”

Stefan stood as the women talked and began whisking used glossleafs off the table, piling them to one side for the convenience of the service staff. Meanwhile, Maiju did them all the honor of serving the sweet, an herb‑flavored ice presented in capacious bowls, with fluted spoons, and accompanied by real shade‑grown Old Earth coffee–a shrub that flourished in the New Amazonian climate.

“A Coalition warship, the Skidbladnir,was destroyed by sabotage during a diplomatic mission headed by Katherinessen. The lack of military assets allowed New Earth to walk away with its sovereignty intact. Another mission was sent, but by the time it arrived, New Earth had managed to scramble enough of a military operation to make the cost of retaking the world excessive, and the Governors would not permit a full‑scale use of force because of the ecological impact. New Earth is marginally habitable at best–it’s cold and has a low oxygen rating and not a lot of water, which made it a poor investment from the Governors’ point of view, as they will not permit Terraforming. During the investigation it came out that Katherinessen had what they would call an improper relationship with his attachй.” Claude’s habitual smile drifted wider as her left hand crept out to take Maiju’s possessively. “I don’t know why they weren’t culled for the…‘crime.’”

“And here he is,” Lesa said, and then slipped her spoon into her mouth and let the ice melt over her tongue, spreading flavors that shimmered and changed as it warmed.

“Guess who they sent along with him?”

Lesa’s spoon clicked on the bowl. “The attachй?”

“Amusing, isn’t it?” Claude steepled her fingers behind her untouched dessert. “They seem to have taken us at our word when we said we would only accept women, or gentle males.”

Lesa shook her head, and drank two swallows of scalding coffee too rapidly, to clear her palate before she spoke. “It’s got to be a trick.”

“Of course it is,” Claude said. “No smart woman would expect the Coalition to deal in goodwill.”

“We’re not either,” Miss Ouagadougou said, who had been so quiet. “We can’t give them what they’re trading for. It’s unexportable.”

“Don’t worry,” Claude said. “We have that covered. We’re not going to give them anything at all. Anything they want, in any case.”

The meeting continued long past midnight. Afterward, Lesa returned home, changed clothes, and rode the lift almost to the top of the towering spire of Pretoria house. She slipped past Agnes and into the Blue Rooms, saying she was going to check on Julian. She stopped, though, and crossed to the outside wall, where she climbed into an archway and watched the snarled sky turn toward sunrise. Lesa’s hair was tangled, leached to streaked black and gray in the nebula‑light. The Gorgon stretched overhead, a frail twist of color like watered silk, far too permeable a barrier to hold anything at bay for long. Pinprick glows slid against it, red and green, and she wondered if the cargo lighter descending across the dying nebula carried the Colonial diplomats.

Lesa hugged herself despite her nightshirt sticking to her skin, despite the jungle beyond the city walls still steaming from afternoon rains. It wasn’t safe to stand here half clothed, her honor left with Agnes outside and nothing between her and a messy death except her reflexes and a half‑kilometer of space.

But she needed the air, and she needed the warmth. And she could hear the stud males sleeping, their snores and soft breath soothing enough that she almost thought about lying down to sleep beside them. Her mother would have her hide for a holster in the morning, of course, but it might be worth it. Elena Pretoria was almost sixty; she was still sharp and stubborn and undeniably in charge, but Lesa was more than capable of giving her a challenge, and they both knew it.

And the men knew which member of the household looked out for them, and they knew there were gentles and armed women beyond the door. Some women were frightened of men–hopelessly old‑fashioned, in Lesa’s estimation. Stud males might be emotional, temperamental, and developmentally stunted, at the mercy of their androgens, but that didn’t make them incapable of generosity, friendship, cleverness, or creativity.

It wasn’t their fault that they weren’t women. And Lesa knew better than to provoke them, anyway. Like any animal–like the house khir that had been Lesa’s responsibility before Katya took over–they could be managed. Even befriended. They simply demanded caution and respect.

Which was something many women were not willing to offer to stud males, or even gentle ones, but Lesa found she preferred their honesty to the politics of women. An eccentricity–but that eccentricity was one reason why she would be the one to meet the Colonials when they came.

The reason besides Katherinessen. She was looking forward to that. She stroked the archway and felt House shiver its pleasure at the touch.

Some people couldn’t sense the city’s awareness of their presence and its affection. Lesa found it comforting. Especially as she considered the thorniness of the problem she faced.

Her mother believed in the process. No matter what, no matter how much wrangling went on between Elena and Claude, Elena believed in the process. In the New Amazonian philosophy.

And Lesa no longer did.

She stepped back. The wall stayed open and a warm breeze chased her, bringing jungle scents and the calls of a night‑flyer. She’d worry about the Colonials tomorrow. Tonight, she picked her way past the sleeping men, brushing a finger across her lips when her favorite, Robert, lifted his head from his arm and watched her go by. He winked; she smiled.

The boys’ quarters were at the back of the Blue Rooms. She pushed past the curtain and held her palm to the sensor so House could recognize her and let her pass. The boys slept even more soundly than the men.

None of them woke. Not even Julian, when she climbed over him and the yearling khir curled against his chest, slid between his body and the wall, and pushed her face into his hair as if she could breathe his rag‑doll relaxation into her bones.

Timeslip. Cold currents on unreal skin. The flesh‑adapted brain interprets this as air on scales, air tickling feathers.

Kii had wings once. Eyes, fingers, tongue. No more. Now, Kii watches the aliens through ghost‑eyes, tastes their heat and scents and sounds through ghost‑organs. No skin‑brush, tongue‑flicker, swing of muzzle to inhale warmth through labial pits.

The aliens are that. Alien. Unscaled, unfeathered. Tool users with their soft polydactyl hands. They totter on legs, bipedal, hair patchy as if with parasites. But after Kii has seen a few, Kii understands they are supposed to look that way.

Sudden creatures, and so strange, with their hierarchies and their false Consent that leaves them unhappy, untribed.

But they know combat for honor, and the care of young, and they keep the khir. And they know art for its own sake.

They areesthelich, cognizant of order. And that is new.

The ghost‑others think Kii’s fascination strange. But Kii is explorer‑caste, a few still remaining–still needed even among the ghosts–and Kii is not content with experiment, manipulation, analysis. The others may engage with cosmoclines, programming, reordering the infrastructure of their vast and artificial universe. They may manipulate wormholes, link branes, enhance control. They have mistressed power enough to manufacture entire branes–objects similar to a naturally occurring four‑dimensional universe–and learned finesse enough to program them. They have aspired to leave their shells and embrace immortality.

Nothing they are or desire cannot be made or remade on a whim. They are beyond challenge. They no longer evolve.

And yet Kii watches the alien curl around its cub as the cub curls around the khir, and Kii sees something new. Perhaps Kii is in need of a programming adjustment, but it is not violating Consent to wonder.

And things that are new are things that Kii’s caste is for.

On fourteen worlds, Vincent Katherinessen had never seen a city like Penthesilea.

The limousine they’d transferred into after the lighter’s splashdown came in low, skimming over the wind‑ruffled bay and the densely verdant forests that grew against the seashell walls of the ancient, alien city. The pilot was giving the emissaries the view; she brought the craft up on an arcing spiral that showed off three sides of the skyline.

Vincent leaned against the window shamelessly and stared. The structures–if they wereindividual structures, given how they flowed and merged together, like tall colonies of some sea animal with calcified exoskeletons–were earth‑shades and jewel‑shades, reflecting a dark oily iridescence like black opal or treated titanium. Vincent wondered if they were solar. The colors were suggestive, but could be decorative–though he couldn’t think of a human culture that would choose that color scheme or the chaotic, almost fractal architecture that put him in mind of something arranged by colony insects, Ur‑hornets or Old Earth termites.

No one really knew. As the OECC had reconstructed from its incomplete access to New Amazonian records, Penthesilea looked more or less as it had when the New Amazonians arrived–the only evidence of nonhuman intelligence that had been found on any explored world. There were four other cities, each miraculously undamaged and thrumming after centuries of abandonment, each apparently designed by an intelligence with little physical resemblance to humans. And each cheerfully polymorphous and ready to adapt to the needs of new occupants who, in the hard, early days of the colony, had determined convenient shelter to be the better part of caution, and who had not been proven wrong in the decades since. Arguments about their nature and design possessed the OECC scientific community and proved largely masturbatory. New Amazonia wasn’t about to allow a team in to research their construction, their design, their archaeology, or–most interesting of all to the OECC–their apparently clean and limitless power source.

So Vincent and Michelangelo were here to steal it. And if they couldn’t steal it–

There were always fallback options.

Vincent glanced at his partner. Michelangelo sat passive, inward‑turned, as if he were reading something on his heads‑up. He wasn’t; he was aware, observing, thinking, albeit in that state where he seemed to have become just another fixture. Vincent nudged him–not physically, exactly, more a pressure of his attention–and Michelangelo turned and cleared his throat.

Vincent gestured to the window. “Change your clothes. It’s time to go to work.”

Michelangelo ran fingers across his watch without looking, and stilled for a moment as the foglets in his wardrobe arranged themselves into a mandarin‑collared suit of more conservative cut than Vincent’s, ivory and ghost‑silver, a staid complement to Vincent’s eye‑catching colors. “Kill or be killed,” he murmured, his mouth barely shaping the words so neither the pilot nor the limousine would hear them.

Vincent smiled. That’s what I’m afraid of.

Michelangelo nodded, curtly, as though he had spoken.

The first thing Kusanagi‑Jones noticed as he stepped down from the limousine was that the pavement wasn’t exactly pavement. The second thing was that there were no plants, no flowers except the freshly dead garlands twined with ribbon or contack that hung from every facade. No landscaping, no songbirds–or the New Amazonian equivalent–just the seemingly wind‑sculpted architecture, buildings like pueblos and weathered sandstone spires and wind‑pocked cliff faces. He stood, tropical humidity prickling sweat across his brow, and arched his neck back to look up at the legendary Haunted City of New Amazonia.

He didn’t see any ghosts.

He’d done his threat assessment before the door of the limousine ever glided open, and he reconsidered it now, as his wardrobe wicked sweat off his skin so quickly he barely felt damp and his toiletries combated the frizz springing up in his hair. He blocked the door of the limousine, covering Vincent with his body, and turned like a shadow across a sundial to scan roofs and the assembled women with his naked eyes and an assortment of augments.

The Penthesilean security forces stood about where he would have stationed them, and that was good. It was good also that the women in the greeting party stayed back and let him make sure of the surroundings rather than rushing in. He hated crowds.

Especially when he was with Vincent.

He moved away, and a moment later Vincent stood beside him. Kusanagi‑Jones’s skin prickled, but there was nothing but the dark opalescent somethingunder his feet, the punishing equatorial sun, and the three women who detached themselves from the dignitaries and started forward. The one in the middle was the important one; older, with what Kusanagi‑Jones identified–with a bit of wonder–as sun‑creases decorating the edges of long black eyes distinguished by epicanthic folds. Her hair was straight and shoulder length, undercut, the top layer dyed in stained‑glass colors, shifting to reveal glossy black. She wore dark vibrant red, what Kusanagi‑Jones thought was a real cloth suit–a blatant display of consumption.

The two behind her were security, he thought; broad‑shouldered young women in dark plain wardrobes or clothing, with the glow of animal health and stern expressions calculated to give nothing away. All three of them were openly armed.

Kusanagi‑Jones knew how to use a sidearm. He’d received training in allthe illegal arts, although he’d never been a soldier. And he’d been on planets raw enough that citizens were still issued permits for long weapons. But he’d never been in the presence of people–especially women–who wore their warcraft on their sleeves.

He wondered if they could shoot.

It made him unhappy, but he stepped to one side and allowed Vincent to take point. The older woman stepped forward, too. “I’m Lesa Pretoria,” she said in accented com‑pat, tendering a hand.

Vincent reached to take it as if touching strangers were something he did every day. He shook it while Kusanagi‑Jones hurried to adjust his filters so he could follow suit. “Vincent Katherinessen.”

“That’s not a Coalition name,” Miss Pretoria said.

“I was born on Ur, a repatriated world. This is my partner, Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones. He isfrom Old Earth.”

“Ah.” A world of complexity in that syllable. Vincent had answered in nearly flawless New Amazonian argot, which owed less to Spanish and Arabic and more to Afrikaans than com‑pat did. She extended her hand to Kusanagi‑Jones. “I’ll be your guide and interpreter.”

Warden,Kusanagi‑Jones translated, taking her hand and bowing over it, painfully aware of her consideration as his wardrobe considered her and let them touch. “The fox.”

She blinked at him, reclaiming her appendage. “Beg pardon?”

“Lesa,” he said. “Means the fox.”

Her lips quirked. “What’s a fox, Miss Kusanagi‑Jones?”

The Amazonian patois had no honorific for unmarried men, and his status here was at least diplomatically speaking better than that of a Mister. So being called Missrelaxed him, although he caught Vincent’s sharp amusement, an undertone flavored with mockery.

Just another mission, just another foreign land. Just another alien culture to be navigated with tact. He smiled at Vincent past Miss Pretoria’s shoulder and bowed deeper before he straightened. “An Old Earth animal. Beautiful. Very clever.”

“Like what we call a fexa,then? A hunting omnivore?” she continued as he nodded. “All gone now, I suppose?”

“Not at all. Seven hundred and fourteen genotypes preserved, of four species or subspecies. Breeding nicely on reintroduction.” He gave her a substandard copy of Vincent’s smile number seven, charming but not sexually threatening. “Featured in legends of Asia, Europe, and North America.”

“Fascinating,” she said, but she obviously had absolutely no idea where those places were, and less interest in their history. “Those are nations?”

“Continents,” he said, and left it at that, before Vincent’s mirth could bubble the hide off his bones like lye. He stepped back, and Miss Pretoria moved to fill the space as smoothly as if he’d gestured her into it–no hesitation, no double‑checking. They fell into step, Vincent flanking Pretoria and himself flanking Vincent, her security detail a weighty absence on either side: alert, dangerous, and imperturbable. Pretoria ignored them like her breath.

Kusanagi‑Jones caught Vincent’s eye as they headed for the reception line. Your reputation precedes you, Vincent. She’s like you.Neither an empath nor a telepath; nothing so esoteric. Just somebody born with a greater than usual gift for interpreting body language, spotting a lie, a misdirection, an unexpected truth.

A superperceiver: that was the technical term used in the programs they’d been selected for as students, where Michelangelo was classified as controlled kinesthetic,but the few with the clearance to know his gift called him a Liar.

He almost heard Vincent sigh in answer. Irritation: do something, Angelo.Not words, of course–just knowing what Vincent wouldhave said.

Kusanagi‑Jones took his cue as they entered the receiving line and tried for a conversation with Miss Pretoria between the archaic handshakes and watch‑assisted memorization of each name and rank. He knew as soon as he thought it that he shouldn’t say it, but it was his job to be the brash one, Vincent’s to play the diplomat.

He leaned over and murmured in Miss Pretoria’s ear, “How does a planet come to be called New Amazonia?”

Her lip curled off a smile more wolf than fox. “Miss Kusanagi‑Jones,” she said, the dryness informing her voice the first evidence of personality she’d shown, “surely you don’t think we’re entirelywithout a sense of humor.”

He shook another stranger’s hand over murmured pleasantries. There was a rhythm to it, and it wasn’t unpleasant, once you got the hang of it. The New Amazonians had firm grips, sweaty with the scorching heat. He wished he’d worn a hat, as most of the women had.

He decided to risk it. “I admit to having worried–”

She didn’t laugh, but her lip flickered up at the corner, as if she almostthought it was funny. “You’ll be pleasantly surprised, I think. You’re just in time for Carnival.”

3

THEY HAD NOT BEEN LIED TO. THE MEN WERE GENTLE; when one leaned, moved, spoke, the other one mirrored. She sensed it in the energy between them, their calm failure to react on any visceral level to her smile, the swell of her breasts, the curve of her hips–or to the more youthful charms of her security detail. She knew it as surely as she would have known fear or hunger. Not only were they gentle, they were together.

She’d been afraid the Coalition would try to send stud males, to pass them off–even to replace Katherinessen with an impostor. These weren’t quite like the gentle males of her acquaintance, though. They were wary, feral, watching the rooflines, eyes flickering to her honor and to the weapons of the other women. She shouldn’t have been surprised. Without women in a position to protect them, gentle males would find rough going in a society dominated by stud males and hormonally driven aggression. She liked the way they backed each other, the dark one and the tawny one, shoulder to shoulder like sister khir against a stranger pack. She wondered how old they were, with their strange smooth faces and silken skin, and the muscled hands that didn’t match their educated voices.

They survived the receiving line without a diplomatic incident, but both men seemed relieved when she ushered them inside. Even filtered by the nebula–invisible in daytime–the sun was intense at the equator, and they weren’t accustomed to it. She’d read that on Old Earth the cities were small, widely spaced, and densely packed, the population strictly limited–through culling and fetal murder, when necessary–and the regenerated ecosystems were strictly off‑limits without travel permits.

She shuddered, thinking of that circumscribed existence, locked away from the jungle for her own protection and the world’s–unable to pick up a long arm, sling it over her back with a daypack and a satphone, and vanish into the bush for a day or a week, free to range as far as her daring would support. She could have been like these men, she realized: coddled, blinking in the bright sunlight–or worse, because a woman wouldn’t rise to their position in the OECC. They’d probably never been outside a filter field in their lives.

Good. That was an advantage. One she’d need, given what Claude had told her about Katherinessen. The legendary Vincent Katherinessen, and his legendary ability to know what one thought before one knew it oneself.

She collected herself and focused on the deal at hand–which was, after all, a deal like any deal. Something to be negotiated from the position of strength that she was fortunate to have inherited. “We’ve arranged a reception before we sit down to dinner. And some entertainment first. If you’re not too tired from traveling.”

Katherinessen’s gaze flicked to his partner; Kusanagi‑Jones tipped his head in something that wasn’t quite a nod. The communication between them was interesting, almost transparent. Most people wouldn’t have even seen it; shecouldn’t quite read it, but she thought she might learn. In the meantime, it was good to know that it was going on, that the dynamic between the two men was not quite the leader‑and‑subordinate hierarchy they projected. Something else developed for navigating a male‑dominated space, no doubt.

“I think we’re acceptably fresh,” Katherinessen said, “as long as our licenses hold out. We both got a lot of sleep on the ship. But it would be nice to have a few moments to relax.”

Lesa wanted to ask if he meant cryo, but wasn’t sure if it would be in poor taste, so she nodded. “Come with me. The prime minister is eager to greet you, but she can wait half a tick.”

“She thought it best not to overdignify our arrival with her presence?” Katherinessen asked. A sharp, forward question; Lesa glanced at him twice, but his face stayed bland.

“I’ve negotiating authority, Miss Katherinessen. Parliament, of course, will have to ratify whatever we agree.”

“On our end, too. I’m assured it’s a formality.” His shrug continued, but so are we always assured, are we not? The raised eyebrow was a nice touch, including her in the conspiracy of those who labor at the unreasoning whim of the state. “Am I supposed to inquire as to the nature of the entertainment?”

She smiled back, playing the game. “It’s the day before Carnival. We thought you might like a real frontier experience, and the Trials began at first light today. If that meets with your approval.”

His smile broadened cautiously. He was really a striking man, with his freckles and his auburn hair. Pity he’s gentle,she thought, and then mocked herself for thinking it. If he wasn’t, after all, he wouldn’t be here. And she shouldn’t be anywhere near him, honor on her hip and security detail or not.

“We are at your disposal, Miss Pretoria,” he said, and gestured her graciously ahead. The security detail followed.

One reason Kusanagi‑Jones trained as rigorously as he did was because it speeded adaptation. He could have taken augmentation to increase or maintain his strength, but doing the work himself gave additional benefits in confidence, balance, and reflex integration. His brain knew what his body was capable of, and that could be the edge that kept him, or Vincent, alive.

That never changed the fact that for the first day or two in a changed environment, he struggled as if finding his sea legs. But as far as he was concerned, the less time spent tripping over invisible, immaterial objects, the better.

So it was a mixed blessing to discover that wherever Miss Pretoria was taking them, they were walking. It would help with acclimation, but it also left Vincent exposed. Kusanagi‑Jones clung to his side, only half an ear on the conversation, and kept an eye on the windows and the rooftops. To say that he didn’t trust the Penthesilean security was an understatement.

“Tell me about these Trials,” Vincent was saying. “And about Carnival.”

Lesa gave Vincent an arch look–over Kusanagi‑Jones’s shoulder–but he pretended oblivion. “Your briefings didn’t cover that?”

“You are mysterious,” Vincent answered diplomatically. “Intentionally so, I might add. Are they a sporting event?”

“A competition,” Lesa answered. “You’ll see. We’re in time for a few rounds before high heat.”

Around them, the atmosphere had textures with which Kusanagi‑Jones was unfamiliar. The heat was no worse than Cairo, but the air felt dense and wet, even filtered by his wardrobe, and it carried a charge. Expectant.

“It gets hotter than this?” Vincent asked.

Lesa flipped her hair behind her ear. “This is just morning. Early afternoon is the worst.”