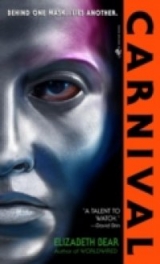

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

Carnival

Elizabeth Bear

For Stephen and Asha

BOOK ONE

The Festival of Meat

1

MICHELANGELO OSIRIS LEARY KUSANAGI‑JONES HAD BEEN drinking since fourteen hundred. He didn’t plan on stopping soon.

He occupied a bubbleport on the current observation deck of Kaiwo Maru,where he had been since he started drinking, watching a yellow main‑sequence star grow. The sun had the look of a dancer swirling in veils, a Van Gogh starscape. Eons before, it had blundered into a cloud of interstellar gas and was still devouring the remains. Persistent tatters glowed orange and blue against a backdrop of stars, a vast, doomed display of color and light. Kusanagi‑Jones could glimpse part of the clean‑swept elliptical path that marked the orbit of New Amazonia: a darker streak like a worm tunnel in a leaf.

Breathtaking. Ridiculously named. And his destination. Or rather, theirdestination. Which was why he was drinking, and why he didn’t intend to stop.

As if the destination–and the mission–weren’t bad enough, there was the little issue of Vincent to contend with. Vincent Katherinessen, the Old Earth Colonial Coalition Cabinet’s velvet‑gloved iron hand, far too field‑effective to be categorized as a mere diplomatic envoy no matter how his passport was coded. Vincent, whom Kusanagi‑Jones had managed to avoid for the duration of the voyage by first taking to cryo–damn the nightmares–and then restricting himself to the cramped comforts of his quarters…and whom he could avoid no longer.

Vincent was brilliant, unconventional, almost protean in his thinking. Unless something remarkable had changed, he wore spiky, kinky, sandy‑auburn braids a shade darker than his freckled skin and a shade paler than his light‑catching eyes. He was tall, sarcastic, slender, bird‑handed, generous with smiles as breathtaking as the nebula outside the bubbleport.

And he was the man Michelangelo Kusanagi‑Jones had loved for forty years, although he had not seen him in seventeen–since the lasttime he had betrayed him.

Not that anybody was counting.

Kusanagi‑Jones had anticipated their date by hours, until the gray and white lounge with its gray and white furniture retreated from his awareness like a painted backdrop. If Kusanagi‑Jones captained a starship, he’d license it in reds and golds, vivid prints, anything to combat the black boredom of space.

Another man might have snorted and shaken his head, but Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t quite permit himself a smile of self‑knowledge. He was trying to distract himself, because the liquor wasn’t helping anymore. And in addition to his other qualities, Vincent was also almost pathologically punctual. He should be along any tick–and, in fact, a shadow now moved across Kusanagi‑Jones’s fish‑eye sensor, accompanied by the rasp of shoes on carpet. “Michelangelo.”

Kusanagi‑Jones finished his drink, set the glass in the dispensall, and turned. No, Vincent hadn’t changed. Slightly softer, belly and chin not as tight as in their youth, gray dulling hair he was too proud to have melanized. But in the vigorous middle age of his sixties, Vincent was still–

“Mr. Katherinessen.” Kusanagi‑Jones made his decision and extended his hand, ignoring Vincent’s considering frown. Not a gesture one made to a business associate.

Through the resistance of their wardrobes, fingers brushed. Hands clasped. Vincent hadn’t changed his program either.

They could still touch.

Kusanagi‑Jones had thought he was ready. But if he hadn’t known, he would have thought he’d been jabbed, nano‑infected. He’d have snatched his hand back and checked his readout, hoping his docs could improvise a counteragent.

But it was just chemistry. The reason they’d been separated. The reason they were here, together again, on a starship making port in orbit around a renegade world. Old times,Kusanagi‑Jones thought.

Vincent arched an eyebrow in silent agreement, as if they’d never parted.

“Kill or be killed,” Vincent said, next best thing to a mantra. Kusanagi‑Jones squeezed his fingers and let their hands fall apart, but it didn’t sever the connection. It was too practiced, too reflexive. Vincent’s gift, the empathy, the sympathythat turned them from men into a team. Vincent’s particular gift, complement of Kusanagi‑Jones’s.

Vincent stared at him, tawny eyes bright. Kusanagi‑Jones shrugged and turned his back, running his fingers across the rainbow lights of his subdermal watch to order another martini, codes flickering across neuro‑morphed retinas. He stared out the bubble again, waiting while the drink was mixed, and retrieved it from the dispensall less than a meter away.

“Oh, good.” Vincent’s Earth patois–his com‑pat–was accentless. “Nothing makes a first impression like turning up shitfaced.”

“They think we’re animals anyway.” Kusanagi‑Jones gestured to a crescent world resolving as Kaiwo Maruentered the plane of the ecliptic and began changing to give her passengers the best view. “Not like we had a chance to make them like us. Look, crew’s modulating the ship.”

“Seen one reconfig, seen them all.” Nevertheless, Vincent came up to him and they waited, silent, while Kaiwo Marureworked from a compact shape optimized for travel to something spidery and elegant, designed to dock with the station and transfer cargo–alive and material–as efficiently as possible.

“Behold,” Vincent teased. “New Amazonia.”

Kusanagi‑Jones took a sip of his martini, rolling the welcome rawness over his tongue. “Stupid name for a planet.” He didn’t mind when Vincent didn’t answer.

Bravado aside, Michelangelo did stop drinking with the one in his hand, and Vincent pretended not to notice that he checked his watch and adjusted his blood chemistry. Meanwhile, Kaiwo Marudocked without a shiver. Vincent didn’t even have to put his hand out to steady himself. He pretended, also, that he was looking at the towering curve of the station beyond the bubble, but really, he was watching Michelangelo’s reflection.

There had been times in the last decade and a half when Vincent had been convinced he’d never exactly remember that face. And there had been times when he’d been just as convinced he’d never get it out of his head. That he could feel Michelangelo standing beside him, glowering as he was glowering now.

One wouldn’t discern it casually; Angelo wouldn’t permit that much emotion revealed. His features were broad and solemn, his eyes stern except when bright. He seemed stolid, wary, unassuming–a blocky muscular man whose coloring facilitated his tendency to fade into the shadows. But Vincent felthim glowering, his displeasure like the weight of an angry hand.

Michelangelo glanced at his watch as if contemplating the colored lights. Vincent knew Michelangelo had a heads‑up; he wasn’t checking the time. He was fidgeting.

Fidgeting was new.

“I don’t love you anymore.” Michelangelo pressed his hand to the bubble and then raised it to his mouth.

“I know. I canstill read your mind.”

Michelangelo snorted against the back of his fingers. “I’m a Liar, Vincent. You’ll believe what I want you to believe.”

“How generous.”

“Just true.” Then the irony of his own statement seemed to strike him. He dropped his head and stared at the tips of his shoes as if hypnotized by the rainbows reflected across them. When he glanced back up, Vincent could read laughter in the way the crinkles at the corners of his eyes had deepened.

Vincent chuckled. He touched his watch, keying his wardrobe to something more formal, and stilled momentarily while the program spread and the wardrobe rearranged itself. “Do you wantme, at least? That would make things easier.”

Michelangelo shrugged, impassive. Vincent turned, now watching him frankly, and wondered how much of the attraction was–had always been–that Michelangelo was one of the few people he’d met that he couldn’tread like a fiche.

“They offered me a choice. Therapy or forced retirement.”

Michelangelo’s coloring was too dark for his face to pale, but the blood draining made him ashen. “You took therapy.”

Vincent stifled a vindictive impulse. “I took retirement. I don’t consider my sexuality something that needs to be fixed.”

“Sign of persistent pathology,” Michelangelo said lightly, but his hands trembled.

“So I’ve been told. The funny thing is, they couldn’t make it stick. I didn’t even make it home before I was recalled. Apparently I’m indispensable.”

Michelangelo’s thumb moved across his inner wrist, giving Vincent a sympathetic shiver at the imagined texture of the skin. Another glass appeared in the dispensall, but from the smell, this one was fruit juice.

He sipped the juice and made a face. “I heard.”

Vincent wondered if the license was off. “And you?”

“Not as indispensable as Vincent Katherinessen.” He put the glass back and watched as it recycled: the drink vaporizing, the glass fogging. A waste of energy; Vincent controlled the urge to lecture. If they got what they needed on New Amazonia, it wouldn’t be an issue–and anyway, they were on a starship, the one place in the entire OECC where conserving energy wasn’t a civic duty as mandated as community service. “I took the therapy.”

Vincent swallowed, wishing he could taste something other than the tang of atomizing juice. He picked a nonexistent bit of lint off his sleeve. “Oh.”

Michelangelo lifted his chin, turned, and gave Vincent a smile warm enough to melt his implants. He glanced over his shoulder, as if ascertaining the lounge was empty, then leaned forward, slid both hands up Vincent’s neck, and pulled Vincent’s head down to plant a wet, tender kiss on his lips.

It’s a lie,Vincent told himself, as his breath shortened and his body responded. Michelangelo was substantial, all muscle under the draped knits his wardrobe counterfeited. They both knew he controlled Vincent the instant Vincent let him close.

Just as Vincent knew Michelangelo’s apparent abandonment to the kiss was probably as counterfeit as his “hand‑knitted” sweater. It’s a lie. He took the therapy. It didn’t help. His body believed; his intuition trusted; the partnership breathed into the kiss and breathed out again. Sparkles of sensation followed Michelangelo’s hands as they cupped Vincent’s skull and stroked his nape. He knewMichelangelo wanted him, as he had always known. As Michelangelo had always permittedhim to know.

He wondered what the ship’s Governors made of the kiss, whether they had been instructed to turn a blind eye on whatever illegalities proceeded between the diplomat and his attachй. Or if their interaction had been logged and would be reported to the appropriate agencies within the Colonial Coalition when Kaiwo Marudispatched a packet bot.

The relationship between the Cabinet and the Governors was complex; the Cabinet did not carry out death sentences, and the Governors did not answer to the Cabinet. But after the Great Cull, they had begun performing some of their Assessments in accordance with planetary laws. There was dйtente; an alliance, of sorts, by which the Cabinet maintained control and the Governors, with their own inhuman logic and society, supported an administration that maintained ecological balance.

Once, there had been many governments on Old Earth. Industrialized nation‑states and alliances had used more than their share of resources and produced more than their share of waste. But Assessment had ended that, along with human life in the Northern Hemisphere. In the wake of an apocalypse, people often become reactionary, and the survivors of Assessment were disproportionately Muslim and Catholic. And in a society where being granted permission to reproduce was idealized–even fetishized–where every survivor meant that someone else had notlived…those who were different were not welcome.

Over a period of decades, in the face of necessity, resistance to the widespread use of reproductive technology and genetic surgery waned. The Governors did not care about the morality of the human‑made laws they enforced. Or their irony either.

So, throughout Coalition space, that kiss was the overture to a capital case. But just this once, its illegality didn’t matter. That particular illegality was why they were here.

Michelangelo leaned back, but his breath stayed warm on Vincent’s cheek, and Vincent didn’t pull away. “They’ll just separate us again when this is over.”

“Maybe. Maybe not. We were useful to them once.”

“Politics were different then.”

“The politics are different now, too.”

Michelangelo disengaged, stepped back, and turned away. “Can’t honestly think we will be allowed within three systems of each other. After New Earth”–Michelangelo’s weight shifted, a guilty tell Vincent could have wasted half a day on if he’d been in the mood to try to figure out how much of what Michelangelo gave him was real–“we’re lucky the Cabinet thought us useful enough to keep alive.”

By Michelangelo’s standards, it was a speech. Vincent stood blinking for a moment, wondering what else had changed. And then he thought about therapy, and the chip concealed in–but isolated from–his wardrobe. Don’t love you anymore.

That would make things easier, wouldn’t it?

“If we pull this off”–Vincent folded his hands behind his head–“The Cabinet won’t deny us much. We could retire on it. I could finally introduce you to my mother.”

A snort, but Michelangelo turned and leaned against the bubble, folding his arms. “If we don’t wind up Assessed.”

Vincent grinned, and Michelangelo grinned back reluctantly. The sour, sharp note in Michelangelo’s voice was a homecoming. “If we bring home justthe technology we’re to negotiate for–”

“Assuming it is either portable or reproducible?”

“–we’re unlikely to find ourselves surplused. I know what a cheap, clean energy source will mean to the Captaincy on Ur. And to appeasing the Governors. What will it mean on Old Earth?”

Michelangelo had that expression, the knitted brow and set muscle in his jaw that meant he agreed with Vincent and wasn’t happy about it. He had to be thinking about Old Earth’s tightly managed population of fifty million, about biodiversity and environmental load and Assessment. Culling.

“On Earth?” Michelangelo would never call it Old Earth,unless speaking to someone who wouldn’t know what he meant otherwise. “Might mean no culls for fifty, a hundred years.”

“That would pay for a lot.” Michelangelo could do the math. Nonpolluting power meant that a larger population could be supported before triggering the Governors’ inexorable logic.

The Governors did not argue. They simply followed the programs of the radical environmentalists who had unleashed them, and reduced the load.

Assessments were typically small now. Nothing like the near‑extermination of the years surrounding Diaspora, because Old Earth’s population had remained relatively stable since nine and a half billion citizens had been reduced to organic compounds, their remains used to reclaim exhausted farmland, reinvigorate desertified grassland, enrich soil laid over the hulks of emptied cities–or simply sealed up in long‑abandoned coal mines and oil wells.

Michelangelo’s nod was curt, and slow in coming. Vincent wondered if he’d been mistaken in pushing for it, but then Michelangelo made him a little present of the smile they both knew tangled Vincent’s breath around his heart. “And if we manage to overthrow their government, steal or destroy their tech, and get a picture of their prime minister in bed with a sheep in bondage gear?”

A heartbeat, but Vincent didn’t even try to keep the relief off his face. “They’ll probably give you another medal you’re not allowed to take home.”

Michelangelo’s laugh might have been mistaken for choking. He shook his head when he stopped, and waved a hand out the bubble at the light over the docking bay, on Boadicca Station’s side. “Light’s green. Let’s catch our bus.”

Pretoria household’s residence was already bannered and flowered and gilded to excess when Lesa arrived home, but that wasn’t limiting the ongoing application of gaud. The street‑level entrance opened onto a wide veranda, and one of Pretoria household’s foremothers had wheedled House into growing a long, filigreed lattice from floor to roof around it. It was a pleasant, airy screen that normally created a sense of privacy without disrupting sight lines, but currently it was burdened with enough garland to drift scent for blocks, without considering the sticks of incense thrust in among the flowers. Those would be lit two evenings hence. In the meantime, misted water would keep the blooms fresh.

Lesa climbed the steps along with the household male who’d accompanied her on her errand. Xavier carried a dozen bottles of wine in a divided wicker holder slung over his shoulder. He was a steady, careful sort; they didn’t clink.

Lesa herself had two bags–the pick of fresh fruit and vegetables from the morning’s markets–and two live chickens in a flat‑bottomed sack, slumbering through their last hours in artificial darkness. It paid to get there early, especially near Carnival, and Elena wouldn’t trust the males or the servants with anything as important as buying for a holiday meal.

Besides, they were all busy decorating.

Katya, Lesa’s surviving daughter, supervised the activity on the veranda, her glossy black hair braided off her neck, unhatted in the sun. “Melanoma,” Lesa said, kissing her on the back of the head as she went by.

Katya was fifteen Amazonian years–twenty‑odd, in standard conversion–and impatient with anything that smacked of responsible adulthood. And she wouldn’t wear her honor around the house; her hip was naked even of a holster. Of course, Lesa–both hands full of groceries, unable to reach her honor without dropping chickens or fruit–wasn’t much of an example, whatever her renown as a duelist twenty years and three children ago.

Katya blew her fringe out of her eyes. “Sunblock.” She rubbed Lesa’s cheek with a greasy finger. “Hats are too hot.”

“On the contrary,” Lesa said. “Hats are supposed to keep you cool.” But it was like arguing with a fexa; the girl just gave her an inscrutable look and went back to braiding a gardeneid garland, the sweet juice from the crushed stems slicking her fingers. “Want help?”

“Love it,” Katya said, “but Claude’s in there. The Coalition ship made orbit overnight. You’re on.”

“They got here for Carnival? Typical male timing.” Lesa stretched under her load.

“See you at dinner.” Katya ducked from under her lapful of flowers and turned so she could lean forward mockingly to kiss the ring her mother wore on the hand that was currently occupied by the sack of chickens.

Inside the door, Lesa passed the groceries to one of the household staff and sent her off with Xavier once he’d kicked his sandals at the catchall. Lesa balanced on each foot in turn and unzipped her boots before hanging them on the caddy. In Penthesilea’s equatorial heat, all sorts of unpleasant things grew in unaired shoes.

She dug her toes into the cool carpetplant with a sigh of relief and hung up her hat, grateful to House for taking the edge off the sun. Claude and Elena would be in the morning room at breakfast, which was still being served. Lesa’s stomach rumbled at the smell as she walked through seashell rooms and down an arched corridor, enjoying the aviform song House brought in from the jungle along with filtered light.

Elena Pretoria was exactly where Lesa had imagined her, on the back veranda with her long hands spread on the arms of a rattan chair–real furniture, not provided by House–her silver‑streaked hair stripped into a tail and her skin glowing dark gold against white lounging clothes. For all the air of comfort and grace she projected, however, Lesa noticed the white leather of her holster slung on her waist and buckled down to her thigh. Elena had a past as a duelist, too, and as a politician. And she wasn’t about to let Claude Singapore forget it, even if Claude’s position as prime minister was enough rank to let her enter another woman’s household without surrendering her honor.

Claude was tall and bony, a beautiful woman with blunt‑cut hair that had been white as feathers since she was in her twenties, and some of the lightest eyes Lesa had ever seen–which perhaps explained the depth of the crow’s‑feet decorating her face. They couldn’t all be from smiling, though Lesa wasn’t sure she’d ever seen Claude notsmiling. She had an arsenal of smiles, including a melancholy one for funerals.

“Lesa,” Claude said, as Lesa greeted her mother with a little bow. “I’m here–”

“I heard. The grapevine’s a light‑minute ahead.”

Claude stood up anyway, extending her hand. Lesa took it. Claude had a politician’s handshake, firm but gentle. “I don’t know why we even have media on this planet.”

“It gives us someone to blame for scandals,” Lesa answered, and Claude laughed even though it hadn’t been funny. “I’m ready. When will they make landfall?”

“Tomorrow. We’re shuttling them down. You’ll come by this evening for a briefing?”

“Of course,” Lesa said. “Dinnertime?”

“Good for me.”

Claude stepped away from her chair, and Elena took it as a cue to stand. “Leaving us already?”

“The Republic never sleeps. And I can hear Lesa’s stomach rumbling from here. I imagine she’d enjoy a quiet breakfast with her family before the madness begins.”

“Claude, I don’t mean to chase you out of your chair,” Lesa said, but Claude was turning to shake Elena’s hand.

“Nonsense.” Claude stepped back, and adjusted her holster. It was a Y‑style, and they had a tendency to pinch when one stood. “I’ll see you tonight. I can show myself out–”

“Good‑bye.” Lesa did walk a few steps toward the door with the guest, so as not to give offense. When Claude was safely gone, she tilted her head at Elena. “Why did she come herself?”

“Probably a subtle message not to try anything tricky. She hasn’t forgiven me for getting her wife ousted from the Export Board, and she still thinks the Coalition can be appeased.” The twist of her mouth revealed what she thought of that idea. It made Lesa restrain a smile: it was also Katya’s moue, and Lesa’s son Julian made the same face when he was concentrating.

Lesa used that image of Julian to keep her voice under control. “As soon as they have what they want, the Coalition will scorch us off the surface. They’re distracting us while they set up the kill.”

“They’d have to justify the ecological damage from an orbital attack to the Governors, and that would be…hard to get approval for, I imagine. They might convince the Governors that we need to be Assessed, however, and brought under control. We’d fight.”

Lesa caught the glint of Elena’s smile. “You heard from Katherine Lexasdaughter.”

“Coded. A packet concealed in the Kaiwo Maru’s logburst as she made orbit.”

Lesa could imagine the resources required to arrange for treason and insurrection to be transmitted in a ship’s identification codes on a governed channel. Katherine was head of the Captain’s Council on Ur, and held a chair in the Colonial Cabinet on the strength of it.

“He’s coming.” Lesa’s chest lightened and tightened both at once. Elena might think she was the saltspider at the center of the web, but Lesa couldn’t allow her to recognize all the layers of machinations here. Elena was not going to be happy with Lesa when things shook out.

Elena’s smile was tight with guarded triumph. “I hate hanging our hopes on a man, even if he is both gentle andhis mother’s son. But he came.”

2

BOADICCA WASN’T THE LEAST CIVILIZED STATION Kusanagi‑Jones had seen, but its status as a cargo transfer point rather than a passenger terminal was evident. New Amazonia’s trade was with other Diaspora worlds, a ragtag disorganization of colonies beyond the reach of Coalition growth–for now, anyway. (Kusanagi‑Jones occasionally wondered if the Governors’ long‑dead progenitors had understood that in their creation, they had delivered unto Earth’s survivors a powerful impetus to expansion.)

Boadicca reflected that isolation. The curved passageways were devoid of decoration, creature comforts, carpeting, kiosks, and shops. The only color was vivid stripes of contack, which scanned the watches of nearby pedestrians to provide helpful arrows and schematics. Kusanagi‑Jones paused to study the patterns, and frowned. “Security risk,” he said, when Vincent looked a question. “Too easy for a third party to match up destination with traveler. Must be short on saboteurs and terrorists here.”

Vincent smiled, and Kusanagi‑Jones read the comment in the air between them. Not anymore.

“Good old Earth,” Kusanagi‑Jones agreed, lapsing out of common‑pat and into a language that wasn’t taught in any school. “If you can’t bring it home, blow it up.”

Secrets within secrets, the way the game was always played. If they couldn’t find a way to bring New Amazonia under OECC hegemony with at least the pretense of consent–the way Vincent’s homeworld Ur had fallen–they would weaken the local government through any means necessary, until the colonials came crawling to Earth for help.

Colonies were fragile, short on population and resources. On Ur, for example, there had been the issue of sustainable agriculture, of a limited gene pool further damaged by the exigencies of long‑distance space travel, of the need for trade and communication with other worlds. Where Ur maintained a pretense of sovereignty and had significant representation on the OECC’s Cabinet, successful sabotage leading to a failure of strength would result in a worse outcome for New Amazonia in the long run. And if Vincent and Kusanagi‑Jones did their jobs as ordered, that was the plan, just as it had been on New Earth.

And just as on New Earth, Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t intend to allow the plan to come to fruition. He also wasn’t foolish enough to think that a second act of self‑sabotage would evade his superiors’ notice.

Vincent defocused as he checked his watch. “I’d kill for a coffee. But our luggage is on the lighter.”

“I hope it was well packed.” Luggagewas an inadequate term; the cargo pod that Vincent had shepherded all the way from Earth under diplomatic seal carried what their documents euphemistically identified as samples. Those samples included, among other objects, Fionha Dubhai’s holographic sculpture Ice Ageand an original pastel by the Impressionist Berthe Morisot. Irreplaceabledidn’t even begin to cover it. And bargaining chipwas only the beginning of the story. There was more back on Earth; this shipment was only to prove goodwill–to show willing, as Vincent would say. Whatever their history, the OECC wasn’t stinting on the tools to do its job, either by bargaining or by blowing things up.

Vincent put a hand on Kusanagi‑Jones’s elbow as they drew up before a loading bay, one identical among many. Two green lights blinking beside the archway indicated their destination. “This is the end of the line.”

“You said it.” They walked forward, side by side, to link their documents into the lighter’s system so the pilot could tell them where to go.

The long New Amazonian day was inconvenient for creatures whose biorhythms were geared toward a twenty‑four‑hour cycle. Lag became a problem in more temperate climes, but Penthesilea was fortunate in that high heat provided a supremely adequate excuse for a midafternoon siesta. During more than two‑thirds of the year, it was followed by the afternoon rains, which signaled the city’s reawakening for the evening round of business.

Lesa cheated and let Julian stay with her while she napped. Walter, the big khir that usually slept in her rooms, was nowhere in evidence–probably off with Katya–and Julian at six and a half local years was of the age when naps were an abomination before the god of men. He sat up at Lesa’s terminal while she flopped across the bed and closed her eyes. She’d seen the problem he was working. He said it was a minor modification of House’s program, though Lesa didn’t have the skills to even read it, let alone solve it, but Julian was so thoroughly engaged that she let him keep tapping away as she dozed, lulled by the ticking of the interface.

That sound blended into the patter of the rain on her balcony so that she didn’t rouse until House pinged her. She opened her eyes on yellow walls shifting with violent sunlight–entirely unlike the gray skies outside–and winced. “House, dial it down, please.”

The light dimmed, the walls and ceiling filling with the images of wind‑rustled leaves and vines. She stretched and rubbed her eyes. “Hello, Mom,” Julian said without looking up from the monitors. “Did you sleep well?”

She rubbed at her eyes and padded across the carpetplant to the wardrobe. “Too well,” she said. “I’m late. Save your work, Julian, and go eat.”

“Mom–”

She paused, a fistful of patterned sylk drawn out into the light, and turned to stare at the back of his head. “You know you can’t stay down here while I’m gone.”

His shoulders drooped, but his hand passed quickly over the save light, and he powered the terminal down before sliding, monkeylike, out of the chair. It was a little too tall for him, so he had hooked his toes over a brace while he worked, and the disentangling turned him into a study in conflicted angles. “All right,” he said, and came to hug her before vanishing through the door, gone before it had entirely irised open.

Lesa dressed for business in the warmth of the evening; the rain would be over before she left. She chose a tailored wrap skirt and the sylk blouse, and belted her honor over the skirt. Claude could take offense at anything, even if Lesa were of a mind to show up anywhere public unarmed. And the skirt would be cool enough; she couldn’t face trousers after the rain, with the hottest part of the year beginning.

Downstairs, she passed Xavier in the foyer, coming in from the decorating. Lesa had taken her own turn earlier in the day. At least it was better than pulling the flowers down, which was the part she truly hated.

She told House she was leaving, and asked it to summon a car. The vehicle was waiting by the time she reached the end of the alley that fronted Pretoria house; a diplomatic groundcar with a male driver, his street license prominently displayed on his shoulder–marking a gentle male, rather than a stud like Xavier. He smiled as she slid in. “Government center?”