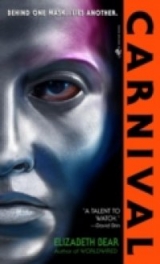

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

“Nkechi,” Miss Pretoria said, “I’ve been asked to hurry Miss Katherinessen and Miss Kusanagi‑Jones back to the government center. Can you see to the relocation of the cargo?”

Kusanagi‑Jones stepped aside and turned in time to see her nod and vanish back inside. He crossed the slight distance between the landing and his partner and took up station at Vincent’s side. His shadow still stretched long on the dock beside him, but the sun was climbing enough to sting where it snuck around the shade of his hat. “Is everything in order?”

“Perfectly,” Michelangelo answered.

Miss Pretoria turned back to them and held up a datacart. She ducked her head, speaking under the shadow of her hat. “A message from my mother, in her role as opposition leader. Countersigned by Antonia. Elder Kyoto, I mean.”

Their habitual security detail flanked them, just far enough away not to overhear if they kept their voices down. Two more women in plain black uniforms remained by the lighter.

“I’m not sure we ever heard her Christian name.” Despite his height, Vincent’s heels rang on the docks with the effort of keeping up with Pretoria; the warden could move when she had to.

She frowned. “That’s an odd term for it.”

Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t have to look at Vincent to know he’d led her into that particular trap on purpose, although his purpose was mysterious. “The first emigrants to Ur were religious refugees,” he said. “It’s just a turn of phrase.”

“Pregnant religious refugees? Miss Katherinessen–”

“Vincent.”

“–I suspect you’re pulling my leg.”

“Some of them were political refugees–”

“Some of usare still waiting to hear about the crisis,” Kusanagi‑Jones said irritably. It wasn’t Miss Pretoria’s leg Vincent was yanking. It was Kusanagi‑Jones’s chain.

“Sorry,” Vincent lied, biting back a widening of his smile.

I never should have fucked him. But he had, whatever advantage it gave Vincent. And he’d do it again.

At least the crisis couldn’t actually be a crisis. Vincent wouldn’t be playing cat‑and‑mouse games with him if it were.

It was a measure of his own stress and his reactions to the New Amazonian culture that his brain spent a full half‑second pinwheeling on the atavistic roots of the phrase cat‑and‑mouse,as archaic to Earth’s governed culture as saying hoist on his own petard. The New Amazonians probably had cats, or the native equivalent. And they probably set them on local herbivores for entertainment, too. When they weren’t enjoying a good duel or a round of cockfighting.

Savages.

Anyway, Vincent was enjoying toying with him far too much for the crisis to be anything overwhelming. In fact, confounding Pretoria’s careful observation of them into that slightly furrowed brow could be Vincent’s entire objective. In which case, Kusanagi‑Jones was content to play the game. He cleared his throat, deciding the silence had gone on long enough.

“In the car,” Pretoria said.

It waited where they had left it, a low‑slung honey‑brown groundcar complete with a wet bar and seats more comfortable than most armchairs. The doors hissed shut after they entered–a perfect seal–and Kusanagi‑Jones used every iota of his craft to appear as if he relaxed against the upholstery, while trying not to picture the animal it must have come from. Cool air shocked the sweat on his neck.

The car rolled forward like a serpent sliding over grass.

“The repatriation ceremony has been postponed,” Miss Pretoria said, and leaned forward in her chair to pull glasses and a decanter of cloudy gray‑green fluid out of the refrigerator. One at a time, she poured three glasses and handed the first two to Vincent and Kusanagi‑Jones. “Any allergies?”

If there were, the nanodocs should handle it. He shook his head and sipped; it looked like swamp water, but tasted tart, with complex overtones. “The reason for the postponement?”

Vincent said, “Officially, a delay in negotiations.”

The artifacts in the cargo pod, officially,were an expression of goodwill–not termed a gift because they already belonged to the New Amazonian people. Negotiations had nothing to do with it. “Unofficially?”

“A threat against the prime minister’s life,” Miss Pretoria said, after a glance at Vincent to see if he was going to speak. “And Miss…and Vincent’s.”

That moment of communication unsettled Kusanagi‑Jones. There was something behind it, and he thought if he had Vincent’s gifts he would know what it was. But Vincent’s hazel eyes were undilated and he met Kusanagi‑Jones’s gaze easily. “Do we know the source of the threat?”

“We suspect the Left Hand. A radical free‑male group. Although it could as easily have been one of the Separatist movements; they put Claude in power, and they can’t be pleased that she’s negotiating with…” Lesa shrugged apologetically.

“Men,” Vincent finished. “These Maenads you mentioned. Is that such a group?”

“The most radical of them. Claude doesn’t actually believe there’s much of a threat, you understand. If enough people wanted to get rid of her badly enough to risk their lives to do it, you’d hear no end to the challenges.” Lesa didn’t quite smile. “We’ve never had an assassination on New Amazonia, though two prime ministers have been shot down in the street when they weren’t fast enough on the draw. So no, we’re cautious, but not too worried.”

“Then why the rush?”

“The ceremony is delayed, but we’re still expected for breakfast. And we might as well see the art installed in the gallery, since we have the time after all.”

“And in the evening?” Kusanagi‑Jones asked, folding his hands around the moist, cold glass. Vincent might not be worried, but when it came to his own personal safety, Vincent was sometimes an idiot. And additionally, Kusanagi‑Jones suspected that Vincent wouldn’t show concern in front of the New Amazonian women.

She smiled. “My mother has invited you to dinner and sightseeing tonight. And of course, there’s Carnival.”

They attended the state breakfast, which thankfully involved less probing‑out of territorial limits and more honest gestures toward dйtente, and a generous quantity of sliced fruit and plain porridge, which Vincent was assured had been prepared without any animal products. He even got Michelangelo to eat, and drink half a pot of tea laced heavily with sugar, and almostmanaged it without pausing to wonder how his partner had survived seventeen years without him.

They’d returned to the gallery by the time Miss Ouagadougou arrived with three lorry‑loads of repatriated art. It came under heavy guard by New Amazonian standards: six armed women and the driver. Vincent couldn’t help comparing the way politicians and dignitaries walked everywhere, attended only by one or two personal retainers, and wondered how the death threat would affect that. On Old Earth, there would be a renewed frenzy of security preparations. Here, with the New Amazonians’ culture of macha, they might just flaunt themselves more. Bravado seemed to be the most likely response.

Michelangelo was going to have a few stern words to say about that, Vincent imagined.

An armed population might cut down on personal crime–although he wasn’t willing to gamble on it unless he had the analyzed statistics graphed on his watch–but apparently property crime was still a problem.

Strike two for Utopia. The problem with the damned things always comes when you try to introduce actual people into your philosophical constructs.

At the gallery, Vincent attempted to assist with the unloading and the decisions on what would be displayed and where, but there were burly men with laborer’s licenses and handcarts and floatcarts for the former, and Michelangelo and Miss Ouagadougou for the latter. And Miss Ouagadougou finally clucked at Vincent and told him that he might as well go for a walk, because he was more in the way than she wanted.

He’d thought he might find a quiet corner and go over his notes from the last day, and attempt to present the appearance of a serious diplomat, but half an hour’s restless flipping through the information on his watch and trying not to distract Michelangelo left him pacing irritably in the anteroom. His focus was compromised. It wasn’t just the variations in gravity, daylight, and atmospheric balance, or the unfamiliar food–in fact, New Amazonia’s oxygen‑rich air was a vast improvement over New Earth’s, to choose a world not particularly at random. He was as accustomed to those things as he was to the slightly folksy Colonial Christian persona he’d been using on Lesa all morning. Adaptation was his stock in trade.

No, he had mission jitters like a first‑timer, aftermath of what he’d just set in motion, and the fact that it was now out of his control. With luck, Robert would see the message in the chip into the right hands, the ones who could decodeit. With luck, they would get a message back to him, and the alliance he’d come to broker–the one in contravention of his supposed OECC loyalties, the one that could allow Ur, New Amazonia, and several other outlying colonies to resist repatriation and governance–could become reality. He might even learn who Katherine Lexasdaughter’s opposite numbers were, if they trusted him enough to arrange a face‑to‑face introduction.

Which they had to if this was going to work. Because the assurances and promises he carried weren’t recorded anywhere except in his head, and he wouldn’t commit them to anyone else.

It was out of his hands, in other words. And there was little Vincent cared for less than trusting to luck.

And the jitters were compounded by standing here, looking at Michelangelo bent in close, professional conversation with Miss Ouagadougou, remembering the smoothness of his skin, the tingle of their wardrobes meshing–

Stop it. He turned away and padded through the other, still‑empty chambers of the museum. One of the security detail detached herself and followed at a respectful distance. Vincent checked his stride to allow her to catch up, folded his hands behind his back, and turned. The chalky surface of the floor felt soft and slick under the balls of his feet. He wondered if the Amazonians ever used carpets or mats, or only bare floors and ubiquitous carpetplant.

The agent was another tall woman, broad‑shouldered and muscular, with a beaked nose, arched eyebrows over dark eyes, and coarse‑grained skin. “I’m sorry, Miss–”

“Delhi.” She didn’t quite smile, but she was thinking about it. “Shafaqat Delhi, Miss Katherinessen.”

“Vincent,” he said. “If I may call you…Shafaqat?”

And there went the smile. She had broad lips, small teeth, very white. A radiant smile. “What’s your pleasure, Vincent?”

No stumble. Much more comfortable with him than Miss Pretoria was. But then, also not personally responsible for the success of negotiations. Vincent had no illusions who would be the sacrifice if the whole careful structure of half‑truths and unmade promises came down on the New Amazonian’s ears.

She still might benefit from revolution. Vincent wanted to see the remnant technology remain in humancontrol, not that of the Governors. At least the Governors’ directive of ecological balance kept their powers in check. But he could envision a Coalition in which those limits did not apply. One in which further growth of the species was allowed, within limits, but every human was fitted not just with a watch, but with an entire series of governor‑controlled utility fogs. It wasn’t the most reassuring concept of the future he’d ever entertained.

And the human government, the Colonial Cabinet, was worse. The Governors were unconcerned with one’s mores,as long as one didn’t reproduce illegally or steal energy, though they’d enforce Coalition laws. God granted Adam and Eve free will and the first damned thing they did with it was find the nearest snake and hand it back.

The agent looked vaguely concerned. “Vincent?”

“I beg your pardon,” he said. “You asked my pleasure.”

“Within my professional capacity, of course.” There was definitely a flirtatious edge on that smile. He might have lost his mind but at least he hadn’t lost his charm.

“Miss Ouagadougou suggested that it might be all right for us to do a little exploring, as long as it wasn’t unaccompanied.” He waved backhanded the way they’d come. Miss Ouagadougou’s laugh followed Michelangelo’s reassuring rumble, their voices echoing from high arched spaces so reverberation obscured the words. “Would you do me the honor of escort?”

She laughed, and he thought he saw respect shade her expression at his willingness to venture out in spite of the threat. And that was important, too; he was sure now that he needed to show himself fearless if he wanted to be in a position to bring these women into an alliance with Ur.

Shafaqat said, “What a delightful invitation. Although I am detailed to protect you. You could have just told me where you wanted to go. It’s Carnival. You should get to play a little.”

“But that isn’t as much fun.”

“I’ll let them know we’re going,” Shafaqat said. “And find out what time your partner wants you home.”

8

WHEN SHE DISCOVERED THAT SHAFAQAT AND MISS Katherinessen were going for a walk, Lesa opted to join them. They left Miss Ouagadougou so enamored of her task that the abandonment barely drew a grunt. Miss Kusanagi‑Jones was less sanguine about the unescorted trip, arguing with Katherinessen in low tones. His unease didn’t seem assuaged by Lesa’s comment that she was capable of squiring Vincent undamaged through the streets, even on the first of Carnival.

As they returned through the galleries, Lesa noticed that Katherinessen was stealing surreptitious sideways glances, and she got the impression that he was looking for some evidence of the fate of the Colonial marines who had died here.

There wasn’t any. House wouldn’t permit lingering damage–and whatever damage there had been, had been from the marines’ weapons. The ghosts didn’t leave scorched or melted walls.

They paused on the carpetplant in the antechamber so that Lesa could slip into her boots, Katherinessen could adjust his wardrobe, and they could both retrieve their hats. The Coalition diplomats seemed to have adapted to the need to keep the sun off their heads. Which was more than she could say for Robert. Lesa could no more keep a hat on him than on their daughter.

Shafaqat seemed relieved to be part of the expedition, although Lesa was aware that the agent bore a certain healthy respect for herself. And that as they stepped outside, she was hovering protectively close to Katherinessen and not to Lesa.

At least, nothing in her manner suggested that she anticipated trouble. Lesa glanced over her own shoulder, made sure of the street, and led them along a latticed walkway that swung thick with garlands, threads of smoke from the incense swaying in the sultry air. “Is there anything in particular you’d like to see?”

“Carnival.” He ticked his fingernails along the lattice. “I’m familiar with a Christian holiday of the same name–”

“We celebrate it in honor of the Gaian Principle,” Lesa said. “Ten days of party before the summer fast of Contemplation. Not a complete fast,” she hastened to add, as Katherinessen turned to her, lips parting. “But we make a point of a bit of spiritual cleansing and contemplation.”

“But it’s not a religious holiday?”

“It’s a spiritualobservance,” she said. “Some follow it more than others. Simple food, no alcohol, meditation, and a focus on community service and charitable giving. A time of renewal, when the jungle dries in the heat before the rains.”

“Contemplation,” he said, shaping it with his lips as if tasting it. “How long is that?”

“Fifty days,” she said.

She saw him running conversions in his head–day length, and year length. “That’s a long time.”

“It’s a pretty good party,” she answered, and met his wrinkled nose with a grin. “It takes awhile to recover.”

She took him on a tour of the administrative center first, Shafaqat trailing them attentively. Seeing her own city through new eyes was an interesting process. He asked questions she’d never considered at any depth, although she was sure there were scientific teams at work on every one of them, and she knew some of the common speculations about this and that and whatever the Dragons might have intended: What are the colors for? Do you have any idea what the shapes of the buildings represent?

It was her city, after all. She’d been born here, and what seemed to Katherinessen alien and fabulous was to Lesa no more than the streets she’d grown up on, the buildings in whose shadows she had played.

“Why do the walls hum?” he asked eventually, when she’d been forced to shake her head and demur more times than she liked to admit.

“The ghosts,” she said, pleased to finally have an answer.

He laughed, as she’d intended, and lifted his fingers to his face to sniff whatever trace of the blossoms lingered there. “You’d expect them to smell sweet,” he said, gesturing to a heavy, wax‑white bloom. “Ghosts?”

Lesa knew what he meant. The New Amazonian pseudo‑orchid had a citruslike scent, not floral at all. “The haunted city, after all,” she said. “The walls hum. Sometimes you see shadows moving from the corners of your eye. Sometimes House takes it upon itself to make arrangements you didn’t anticipate. We still don’t know everything Penthesilea is capable of.”

“But you live here?”

“In a hundred years, it’s never acted in any way contrary to our interests. When the foremothers arrived, there was nobody here but the khir. It took care of them, too.”

“The pets.”

“Domesticated by the Dragons. We think. Symbiotes or pets.”

“And left behind when the Dragons–”

“Went wherever they went. Yes.”

“Reading the subtext of your remarks, the city adapts?”

“House. We call it House. And yes. It understands simple requests, makes whatever we need that’s not too complicated–appliances or electronics or fluffy towels–and cleans up. Most people don’t notice the hum. You must have sensitive hands.”

“The hum is its power source?”

“Or maybe its heartbeat. If it’s alive. But it’s probably just a vast, abandoned fog, still cleaning up after the family dog millennia later.”

Katherinessen didn’t answer for a minute. They were leaving the government center and the streets were starting to fill up. Not just the pedestrian galleries, but the roadways themselves were full of women and men, heads crowned with garlands and necks hung with beads, swathed in gaudy, rustling paper costumery that Katherinessen seemed to be making an effort neither to reach out for nor flinch away from.

“That’s sad,” he said. “When you think about it. You don’t know what happened to the Dragons?”

“We don’t,” she said, both alert to his prying for information and fighting the urge to trust him. Everything she could read on him said he was honest–as honest as a double agent could be–and the chip’s information confirmed everything she thought she knew. She had to raise her voice to carry over the street noise, the melodious thunder of a steel drum. “But I believe they died. Somehow.”

His eyes were shadowed under the hat when he turned them on her, but they still caught fragments of light and glowed like sunlit honey. “You have a reason to think so?”

“Miss Katherinessen,” she said, leading him around the crowd gathered about the musicians, out of the shade gallery and into the hotter, less‑crowded street, while Shafaqat followed five steps behind. “I guess you’ve never had a pet?”

It could have been a facetious question, but he saw by her eyes that she was serious. “No,” he said. “Tamed animals aren’t permitted in the Coalition. It’s unnatural.”

“A lot of animals have symbiotes,” she said, threading through the pressing crowd.

Michelangelo would have a fit. All these people, and not just close enough to touch, but packed together so that one could not avoid touching. The streets were a blurof people, brightly clothed, drenched in scent or sweat or both, hatted and parasoled against the consuming light. The clamor of music was everywhere, instruments he recognized from historical fiche and instruments he didn’t recognize at all, and ancient standbys like saxophone, trombone, and keyboard synthesizer, as if the entire city had spontaneously transformed into something that was half marching band and half orchestra.

Pedestrians threw money to some musicians. Others had no cup out, and accepted beads or garlands of flowers or offerings of food. He couldn’t follow one song for more than a bar or two–they laddered up each other and interwove, clashing. The sheer press of people was as dizzying as the heat.

Vincent surreptitiously dialed his wardrobe down and hurried to keep up with the warden. “You don’t think it’s immoral to enslave animals?”

“I don’t think it’s slavery.” She paused by what he would have called a square, a pedestrian plaza, except it was anything but square. Or geometrically regular, for that matter.

He should have known better than to continue the same old argument, but if he could resist an opening, he wouldn’t have the job he did. “And what about treating your husband as chattel? Is that not slavery?”

“I’m not married,” she snapped, and then flushed and looked down. Shafaqat coughed into her hand.

Vincent concealed his smile, and filed that one under touchy subjects. “And?”

“No,” Pretoria said. “It’s not slavery either. You hungry?”

She looked him straight in the eye when she changed the subject, which was how Vincent knew she was lying. And her smile when he rocked back said she saw him noticing. That would be entirely too convenient.

“I could eat,” he said, though the bustling mall reeked of acid sweetness and perfumes and scorched flesh.

“This is the place to get lunch. I think we can find you something that was never self‑aware, although you may be forced to eat it seasoned with a flying insect or two.” She extended her arm, which he took.

“I can live with the death of a few bugs on my conscience.”

“Hypocrite,” she said. But she laughed. “Doesn’t it get tiring being so damned morally superior all the time?”

Kusanagi‑Jones managed to forget Vincent’s absence quickly. Miss Ouagadougou was pleasant, efficient, and capable, and there was a lot of work to accomplish. The three largest pieces would form the backbone and focal point of the display. Two of the three were twentieth‑century North American–one just a fragment, and both remnants of a much larger public artwork.

Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t think those anything special. Perhaps they’d be more meaningful in context, but it seemed to him that their status as cultural treasures was based on their provenance rather than on their art. They were historical works by women; it might be enough for the New Amazonians, but Kusanagi‑Jones hoped his own aesthetic standards were somewhat higher.

The third piece, though, he couldn’t denigrate. Its return was a major sacrifice, big enough to make him uneasy. The level of commitment betrayed by the Cabinet permitting such a treasure to slip beyond its grasp indicated desperation. Desperation, or no actual intent to let the sculpture go for long.

Officially, Catharine Kimberly was considered a minor artist, but Kusanagi‑Jones had seen some of her other work, and he didn’t think Phoenix Abasedwas the aberration that most scholars maintained. It was a marble sculpture–real marble, quarried stone, one of the last. Larger than life‑size, it depicted a nude woman overcome with grief, her hips twisted by a drawn‑up knee, her upper body thrown forward as if she had been knocked down or she was prostrating herself, sprawled into the abject line of her extended arms, which she seemed–by the sprung muscles of her neck, buttocks, and torso–to be fighting the miring stone.

They weren’t precisely arms, though. Where reaching fingers should have splayed, consuming stone gave the suggestion of wings. Broken feathers scattered the base of the sculpture, tumbled down her shoulders, tangled in the mossy snarl of hair framing her pain‑saturated face. Her head was turned, straining upward, her mouth open in a hurtful Oand her eyes–roughly suggested, thumbprint shadows–tight shut. As if her wings were failing her, crumbling, shed, leaving her mired in unhewn stone.

And now that her wrappings were off, and he stood before her in person, he could see what the fiche couldn’t show. She did not merely grovel, but struggled, dragging against the inexorable stone and wailing aloud as it consumed her.

Her body was fragile, bony, imperfect. She was too frail to save herself. She was devoured.

Perhaps the artist was only a woman. Perhaps she’d never created another work to compare to this raw black‑and‑ocher‑streaked masterpiece. But then, she might have, might she not? If she had lived.

And this was enough. It had impact,a massive weight of reality that pressed his chest like a stone. His eyes stung and he shivered.

Whatever the evidence of her name–and Kusanagi‑Jones would be the first to admit that pre‑Diaspora naming conventions were a nightmare from which he was still trying to awaken–Catharine Kimberly had been a dark‑skinned South African woman who lived at the time of first Assessment and the rise of the Governors.

Operating under their own ruthless program, the Governors had first subverted the primitive utility fogs and modulars of their era, turning industrial and agricultural machines to the purpose of genocide. Domestic animals and plants had been the first victims, destroyed as the most efficient solution to a hopeless complex of ethical failings. Better to die than reproduce as chattel.

Then the Northerners had been Assessed, for their lifestyle and history of colonial exploitation. Following that, persons of European and Chinese descent, regardless of talent or gender.

Billions of corpses produced an ecological dilemma resolved through the banking and controlled release of organic compounds. Salvage teams were allowed to enter North American, Asian, and European cities, removing anything of cultural value that they could carry away, and then the cities were Terraformed under layers of soil produced by the breakdown of human and agricultural detritus.

After that, the tricky work began.

During the Vigil–the seven‑year gap between first Assessment and the final extensive round–those survivors who could find a way were permitted to take flight. At the end of the Vigil, those remaining on Earth had been culled, using parameters set by the radicals who had created the Governors and died to teach them to kill.

The exempt were an eclectic group. Among them were poets, sculptors, diplomats, laborers, plumbers, scientists, engineers, surgeons. Those who created with their minds or with their hands. A chosen population of under fifty million. Less than one in two hundred left alive.

Catharine Kimberly had been spared that first Assessment. And so she had completed Phoenix Abased. And then she had taken her own life.

Which was a sort of art in itself.

Kusanagi‑Jones reached out, left‑handed, and ran his fingers down the cool, mutilated stone. It was smooth, flinty to the touch. He could pretend that he felt some energy in it, a kind of strength. Mysticism and superstition, of course, but Kimberly’s grief gilded the surface of her swan song like a current tickling his fingertips. He sniffed and stepped back, driving his nails into his palm. And looked up to find Miss Ouagadougou smiling at him.

“It’s a powerful piece,” she said, kindly patronizing. Just an emotional male, after all.

He smiled, and played to it. “Never actually seen it before. It’s revered–”

“But not displayed?”

“Not in Cairo,” he said. “We don’t travel to other cities much. Wasteful. It’s different to touch something.” He shrugged. “Not that I would rub my hands over it normally, but–”

“Curator’s privilege,” she said. She bent from the waist, her hands on her knees, and stared into the wailing woman’s empty eyes. “Tell me about your name.”

“My name?”

She turned, caught him with a smile. Like all the New Amazonians, she seemed old for her age, but also fit, and his threat‑ready eye told him that she was stronger than she looked. “Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones. Quite the mouthful. Are those lineage names?”

“Michelangelo–”

“For the artist, of course. Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni.”

“Show‑off,” he said, and her smile became a grin. She straightened up, hands on her hips, and rolled her shoulders back. Volatile male, he thought, and Lied to her a little. It wasn’t hard. If he didn’t think about it, if he wasn’t consciously manipulating someone, it happened automatically. He wasn’t sure he’d know an honest reaction if he had one. And if Miss Ouagadougou wanted to flirt, he could flirt with the best.

Second‑best. There was always Vincent.

“Yes,” he said. “For the artist.”

“And Miss Katherinessen is named for Vincent van Gogh?”

He backed away from Phoenix Abasedand framed it with his hands. “Named for the twentieth‑century poet. Edna St. Vincent Millay. Ur has its own conventions. And his mother is a fan.”

“And what about the rest of it?”

“Katherinessen?”

“No, I understand a matronymic. Osiris.”

“Egyptian god of the dead. After the Vigil and the second Assessment, most of the survivors…you understand that it was rare for more than one member of a family to survive.”

“I understand,” she said. “I think the Glenna Goodacre piece should be in the middle. The Maya Lin fragment to block sight lines as one enters”–it was an enormous mirror‑bright rectangle of black granite, etched with a list of men’s names–“and then as you come around, Goodacre and Kimberly beyond.”

“Saving the best for last.”

She paced him as he continued to back away, trying the lay of the hall from various perspectives. “Precisely. So your ancestors…constructed new families? Renamed themselves?”

“After heroes and gods and historical figures.”

“And artists.”

“Sympathetic magic,” Michelangelo said. “Art was survival.”

“For us it was history.” Miss Ouagadougou slid her fingers at full extension down glossy black granite. “Proof, I guess–”

“Of what came before.”

“Yes.” The tendons along the side of her neck flexed as she turned to stare at him. “Do you wonder what it was like?”