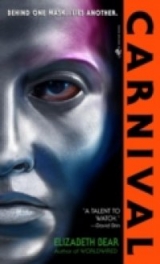

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

“House,” he asked, “which way to the infirmary?”

The ripple of brightness was expected this time, a pattern of motion designed to catch a predator’s eye just the way light snagged on the V‑shaped track of a big fish underwater.

If he had to take a guess, he’d wager that was what Dragons ate. It made sense of the jaw full of slender, needle‑sharp back‑curved teeth, the sharply hooked talons. Following the light, he thought about that, distracted himself with images of arrowing, broad‑winged green‑and‑blue beings hauling great silver fish squirming from the protected waters of the bay.

They were far superior images to the one that persisted when he did not force himself to think of something frivolous.

The rill led him through cool rooms and several corridors, his feet passing over carpetplant and what passed for tile the way the strand of light passed over moving images of jungle understory. He memorized this route, too. It was always good to know how to get out of whatever you were getting into.

He smelled cut greenery, and then cooking, and finally the hospital reek of antiseptic, adhesive, and synthetic skin. The pale glow lingered around a closed iris. Vincent paused and rested his fingertips against the wall beside the door.

“House, open the door, please.”

It spiraled obediently wide. This was a public space, and there was no reason for House to forbid him entrance.

The murmur of voices washed out as he stepped inside. Or a voice, anyway. Katya bent over a flat‑topped table covered with layers of folded cloth, one hand on the neck of the animal she whispered to and the other on his muzzle. It looked as if the bandages had been changed.

Girl and khir were alone in the room. Katya glanced up, tensing, at the sound of the door. Walter might have lifted his head, but she stroked his neck and restrained him, and he relaxed under her hand. She also seemed to calm when she saw Vincent, but he knew it for a pretense. Her shoulders eased and her face smoothed, but no matter how softly she petted the khir’s feathers the lingering tension in her fingers propagated minute shivers across his skin.

Vincent cleared his throat. “Just how smart is a khir?”

She smiled. “Smart.”

“As smart as a human?”

“Well,” she said, stroking Walter’s feathers back along the bony ridge at the back of his skull, “not the same kind of smart. No. They don’t use tools or talk, but they understand fairly complicated instructions and they coordinate with humans and with their pack mates.”

“So they must communicate.”

“Oh, yes.”

“Pity he can’t talk,” Vincent said, sadly.

Katya colored, olive‑tan skin pinking at the cheeks. “Miss Katherinessen,” she said, “I’m sorry about Miss Kusanagi‑Jones. I want to offer my personal assurances that I and everyone in Pretoria house will do everything we can to find him and bring him home safe. Agnes is coordinating the search now, and I’ll relieve her in the morning.”

As if her words were permission, he stepped over the threshold and came fully into the room. The white tile floor was cool, even cold, shocking to feet that had already grown accustomed to carpetplant and the blood‑warmth of House’s hallways. “I shall be praying for your mother,” he said, “and her safe and timely return.”

“Thank you,” she said after a hesitation, and licked her lips before she looked up again. “Do you pray often?”

“Sometimes.”

“Ur is a Christian colony.”

“Founded by Christians. Radicals, like New Amazonia.”

She kept her eyes on the khir, as if watching him breathe. He lay quietly, the nictitating membrane closed under outer lids at half‑mast. She smoothed his feathers again. “We’re taught that Christians were among the worst oppressors of women. On Old Earth. That they held women responsible for all the sin and wickedness in the world.”

He chuckled. “Not my branch of the Church. We’re heretics.”

“Really?” She brightened as if it were a magic word. “Like Protestants?”

He shook his head and reached out slowly to lay his hand on Walter’s flank behind the bandages. The khir’s hide was soft and supple under scales like beads on an evening gown, pebbled against his fingertips. The khir sighed as another breath of tension left his muscles. Vincent’s own heart slowed, the ache across his shoulders easing in response.

“Descended, philosophically speaking, from the very first heresy of all. One that was eradicated by the Paulines about two and a half thousand years ago, for being prone to sentiments that were thought to undermine the authority of the Church.”

He had her interest. She brushed the back of his hand and he could feel her trembling, though she restrained the appearance of it well. “But was it really a…church yet?”

“There was a bishop.” She laughed, so he continued. “Who didn’t approve of their ideas, such as that the Christ might speak to anyone and not solely through the Apostles, and that God was both masculine and feminine and thus women might serve equally as well as men, and that the passion of the Christ was a physical ordeal only, and did not affect his divine essence, and so martyrdom was kind of silly. You know, the usual heresies.”

“And you believe all that?”

He smiled and turned his hand over, pressing it to hers palm to palm. “I was raised to. My mother’s philosophy is a utilitarian one. She believes the purpose of religion, or government, is to maintain the maximum number of people in the maximum possible comfort. And so it suits her to believe that what the serpent offered Eve in the garden wasn’t sin, but self‑knowledge. Enlightenment. Gnosis.”

Katya shook her head. “That’s supposed to be the story that was used to justify oppressing women.”

“But what if the snake did her a favor?”

“Then Eve’s not the villain. Your mother’s supposed to be some kind of a prophet, isn’t she? On your home world?”

“Gnostics believe that anyone can prophesy, if the spirit moves them. She is”–he shrugged–“very good at getting people to listen to her. On Ur, and elsewhere. Enough so that even Earth has to deal with her.”

She squeezed lightly before she pulled her hand away. “Okay, you said you were raised to believe that. But you didn’t answer my question.”

He grinned and let her let go. “Do you believe everything you’re taught, Miss Pretoria?”

When she paused and swallowed, it was all there in her expression, for far longer and much more plainly than she would have liked. How Lesa had missed it, Vincent couldn’t imagine.

Of course, he’d missed Michelangelo’s duplicity. And even for a Liar, that was an impressive trick. The hardest people to read were the ones one was most emotionally attached to, because one’s own projections and desires would interfere with the analysis. One would see what one wanted to see.

There was no surprise in not noticing the knife in Brutus’s hand.

Katya Pretoria stepped back, shaking filthy locks of hair out of her eyes. Flecks of blood stuck the strands together. “Of course I don’t,” she said. “Now, if you will excuse me, Miss Katherinessen, I’m going to get Walter upstairs and try for some sleep myself. I have to relieve Agnes in the morning.”

Kii watches the rust‑colored biped climb. Its heartbeat is fast, blood pressure elevated, serotonin levels depleted, blood sugar dropping, lactic acid levels high, breathing shallow. It is, in short, exhausted, hungry, and dangerously emotional.

Kii waits until it regains its temporary refuge and is alone, in what the bipeds call privacy. Then he clears the wall and appears. “Greetings, Vincent Katherinessen.”

“Kii,” it says. “I was just about to call you. I know the Consent is that you will not assist me–”

“You wish to know if Kii can locate Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones.”

“I wish it, yes.” The biped pauses its speech, but not its motion. If anything, the short quick steps appear to Kii like a futile struggle against the inevitable edict. “And Lesa. Katya Pretoria knows what happened.”

“It shoots Kusanagi‑Jones in the back,” Kii says.

The russet biped rounds on Kii’s projected image, manipulators clenching. “What?”

“Your mate is unharmed,” Kii adds speedily. “It is struck by a sedative capsule. No permanent damage inflicted. Lesa Pretoria is also uninjured, and is restrained in a tangler.”

This linear, discursive mode of communication is vastly limited and inefficient, prone to misparsing. It requires finesse to communicate accurately in this fashion. How much more elegant to present information in poem matrices, with observed, stipulated, speculated, and potential elements clearly identified and quantified by the grammar of the construct.

The Katherinessen biped sinks on the edge of the bed, elbows on its legs, manipulators that seem powerful for its size dangling between its knees, knuckles facing. “Where are they?”

Kii accesses records, flicks through House’s files. At last, reluctantly, Kii says, “They are not in range of House’s nodes.”

“They’re out of the city. In the jungle?”

“That follows as a strong potential.”

“Hell,” the biped says. “Now I have to tell Elena that her granddaughter is a traitor. I do not get paid enough for this.”

19

LESA WOKE COLD, A NOVEL EXPERIENCE IN PENTHESILEA in summer. Her hands in particular were numb (the left one beyond pins‑and‑needles and into deadness), her ankles sore, her neck cramped from lying slumped on her side. The hair that dragged through her mouth was foul with blood and dirt and the acrid bitterness of tangler solvent, and she spat and spat trying to clear it away.

She lay on an earthen floor, and she could smell the jungle. Smell it–and hear it. Night sounds, which explained why her eyes strained at darkness. The canopy filtered daylight, but blocked the Gorgon’s light almost entirely. She heard birds and insects–and a fexa’s warble, closer than she liked, even if she was lucky and there was a stout stockade between them.

She flexed and kicked but didn’t learn anything that surprised her. Her wrists were bound at the small of her back and her ankles strapped. When she lifted her head, her neck amended its status from painful to excruciating, and she fell back, trying to ease the spasm, crying between her teeth.

Incapacitating pain was the first priority. That, and getting her weight off her left arm.

A wriggle of her hips flopped her onto her back, yanking her wrists against the cords. This position was no kinder to her hands, but she bore the pressure and the cutting tautness for the sheer, blessed relief of letting the earth support the weight of her head.

Something feather‑quick and many‑legged scurried across her ankle, but she managed not to react. Pointless caution. She’d made enough noise already that one little thrash and scream would cause no harm. But most New Amazonian “insects” were completely disinterested in any Old Earth fauna that wasn’t actively forcing them to defend themselves. Lesa guessed that when it came down to it, human type people just smelled wrong.

Something stretched on her left side, close enough that she could feel the heat radiating from it and hear the slow hiss of breathing, in and out. Now that Lesa could concentrate on something other than the pain in her neck, she smelled unwashed male over her own sweat and tangler solvent. The solvent explained why she was cold. The stuff was something like 95 percent isopropyl alcohol.

Michelangelo. She got her knees drawn up, straps cutting the tendons of her ankles, and with one hard shove flopped onto her right side. Pain seared up her neck and her left arm sizzled violently to life. She had preferred it, she decided, when it was flopping from her shoulder like the corpse of a dead animal.

Kusanagi‑Jones wasn’t cold. She pressed against his back, but he breathed regularly, his body swaying in response to her nudges with the fluidity of deep unconsciousness. Her right shoulder and upper arm scraped earth painfully as she squirmed closer, writhing over broad shoulders to press her face against the close‑clipped base of his skull. As she cuddled up, she realized she heard two sets of snores–Kusanagi‑Jones’s, faintly, and muffled as if through walls, a louder rasp.

I hope Vincent’s not the jealous type.Gallows humor. The pain of one bitten‑off chuckle brought tears to her eyes.

“Miss Kusanagi‑Jones.” She heaved herself against him. Every movement jostling her neck felt as if somebody had run electrified wires under her skin. “Miss Kusanagi‑Jones!”

His breath caught and a light moan fluttered at the back of his throat, but he didn’t wake. She lowered her head and shoved, smacking her head into his neck. “Dammit, Michelangelo.”

He vanished.

A second later, air cooling against her chest, she realized she hadfelt him move. One moment, Kusanagi‑Jones was a yielding obstacle rocking in time to her efforts. The next, she was alone in the dark, and something thumped–a meat‑on‑bare‑earth sound–followed by silence.

And then a voice, barely a breath. “Miss Pretoria?”

She sighed, trying not to dwell on the strength it would have taken to flip himself to his feet while bound wrist and ankle. “Very impressive. So how are you at square knots?”

Michelangelo’s wardrobe wasn’t functioning, information delivered quite unceremoniously by the weight of imitation cloth on his shoulders. He couldn’t tell if it had failed due to power drain or because of exposure to an electromagnetic pulse weapon of some sort.

The wardrobe was shielded, but shielded was not invulnerable. His low‑light add‑ons, his watch, and his other sense enhancements weren’t functioning either, which told him it was a power problem and not just the wardrobe. But in the case of failure, the fog assumed a default configuration. In Kusanagi‑Jones’s case, his gi–and that was what hung around him now with a strangely materialweight.

A quick triage would not rank a malfunctioning wardrobe as the greatest of his problems. The foglets would have made short work of his restraints, but he was trained to operate without them. No, the immediate problem was one of where he was being held, and how to get out of there.

“Keep talking,” he said. “I don’t want to step on you.”

“What would you like to talk about?”

The voice located her. He sat in a different direction, with as slight a thump as he could manage. The rammed earth didn’t give. He rolled onto his back, lifting his legs, forcing his arms down against cords that cut at his wrists.

“Talk about anything,” he said, keeping his voice as level and soft as he could. She didn’t need to know about his pain.

“I heard someone snoring before you woke. I think our guard is napping against the wall.”

“Who do you think is holding us?”

“Right Hand,” she answered immediately.

Discomfort escaped him on a hiss as he stretched to work his arms around his hips, dragging his shoulders down. “Why?”

“Well,” she said, “we know it’s not Parity. And whoever it is has dragged us off to a hut in the jungle, where you might expect bandits and runaways.”

His hands were free suddenly, with a scraping pop. Or, not exactly free, but bound behind his knees rather than behind his back. Awkward, but easily remedied, and once he got them around his feet, he had teeth. A bloody good thing they hadn’t had shackles. “You weren’t kidding about pirates.”

“No,” she said. “Damn Robert to a man’s hell anyway.”

Kusanagi‑Jones brought his legs up, hooked his hands under his heels, and stretched and wriggled until blood broke through his scabbed wrists and trickled across the skin. If he had Vincent’s loose‑limbed build, this would be easy, but long flexible arms were another of the advantages that hadn’t made it into Kusanagi‑Jones’s heritage.

He made it happen anyway, and then sprawled on his back, panting as quietly as he could manage while blood dripped off his thumbs and spattered his chest. It wouldn’t soak into the gi the way it would real cloth, but it could seep between the minuscule handclasped robots that made up the utility fog, and there was no way he was getting it out of there–short of wading into the ocean–until he found a power source.

“Ow,” he said. “Ever noticed this doesn’t get easier?”

“Indeed,” she said. “I have.”

A good smearing of blood and sweat hadn’t made the thin cords binding his wrists any simpler to manage. They were tight enough that they’d be more accessible if he gnawed his thumbs off first. Also tight enough that he wouldn’t even feel it much.

Which would defeat the purpose of getting his hands free. Instead, he dug at the cords with his teeth, scraping at the fibers and working as much mayhem on his own flesh as on the bindings. But eventually he heard a pop and felt a cord part, and the constriction loosened.

The next thing he felt, unfortunately, was his fingers. Which made him wish for one long, brutal instant that he’d just been a good well‑behaved secret agent and lain there peaceably waiting for the firing squad.

The pain filled his sinuses, flooded his nostrils, floated his eyes in their orbits. It was physically blinding–he couldn’t see the darkness for the flashes in his vision. Beyond pain, and into a white static he couldn’t see or move or breathe through. Michelangelo gritted his teeth, pressed his forehead to thumbs while tears and snot streaked his face, and held on.

It would crest. It would peak and roll back.

All he had to do was live through it.

All he had to do–

He wheezed, hard, when his diaphragm finally relaxed enough that he could get a breath, and then threw his head back, panting. “Bugger,” he said indistinctly, and let his hands fall against his chest.

His fingers felt thick and hot, and they bent only reluctantly, but he could feel them, and they hurt less now than did his wrists.

“You ever needed to disprove the existence of a Creator God,” he said, “the miracle of efficiency that the human body isn’t would be a fucking good place to start.”

“Miss Kusanagi‑Jones?”

Deities or not, there was obviously still room in the world for miracles. Miss Pretoria honestly sounded scared.

“Under the circumstances, call me Michelangelo. Will you roll onto your stomach, please?”

Her wrists were more important than his ankles. He knelt over her, hands on either side of her waist, and used his teeth on these cords, too. His fingers weren’t strong enough.

She whimpered once or twice, but overall, he thought she made less noise than he had.

When he was done, and she was taking her turn coiled shaking around the agony of returning circulation, he sat up and began fumbling at the strapping on his ankles. It was adhesive, wound tight, but he managed to feel the torn edge. It came off noisily, along with a generous quantity of hair.

A ripping sound in the darkness, followed by a series of half‑breathed “ow”s, informed him that Miss Pretoria didn’t need any instruction in order to follow his example. “Now I understand why males complain so much about waxing their backs for the Trials,” she murmured, barely audible under the sawing and bowing of whatever animals infested the jungle night.

Kusanagi‑Jones stifled a laugh. “Hold onto that strapping,” he said. “Might come in useful.”

“It’s sticky.”

“And strong,” he answered, attempting to disentangle his own length so as to wind it around his waist. “See anything yet?”

“Now that you mention it, it might be graying. Slightly.”

He thought so, too. If the walls were boards, as he suspected, and the roof was thatch, the slivers of faint brightness he saw might very well disclose the first grayness of morning. The exotic noises outside were increasing in volume, frequency, and complexity.

Dawn was coming.

“You don’t have a theory why pirates would want to kidnap a couple of diplomats, do you?”

“Not yet,” she answered, and now he could make out enough of her silhouette to see her, head bent, tucking the strapping around herself like a sash. “I’m also curious about how they’ve come to recruit so many young women.”

“Including your daughter.”

She lifted her head to stare at the dimly outlined wall. Her lips were pursed. Her eyes caught the growing light, glistening. She didn’t blink. “Maybe they’re all the daughters or sisters or lovers of males associated with the Right Hand. Maybe…” She sighed and shrugged. “I don’t know. If they can infiltrate Pretoria house, they could be anywhere.”

“Could be facing a revolution.”

She licked her lips, turned, and blinked at him. “Did you think for a moment there was a possibility we aren’t? Come on. Let’s make a break for it.”

She shook herself and moved toward the door they could now see outlined against the far wall, her hand twitching toward a nonexistent weapon. The door was chained around the post, but Kusanagi‑Jones thought he could handle it. He touched the chain, stroked it, rust rubbing off on his fingertips. That chain would hold against anything he could manage barehanded.

The planks of the door, on the other hand…

“Sneak, or rush?” he asked Miss Pretoria.

She crouched beside him, examining the door. “There will be a stockade,” she said. “If they have any sense. A kind of barrier of cut thorn trees.”

“A zareba.”

She blinked at him. “I don’t know that word.”

There was enough light now to show a smile, so he made it a good one. “If you had ever lived in Africa, you would. Before the Diaspora, people walled themselves in with stockades made of thornbushes, to keep out predators like hyenas. Village was called a kraal or enkang. Stockade was a zareba.”

For a moment, he thought she was about to ask him what a hyena was, but instead she returned his smile and dusted her hands on her knees. “Miss Kusanagi‑Jones, I think that’s the longest speech I’ve heard you make.”

He grunted his answer and stepped back, gesturing her to one side as he squared himself before the door. She went, standing with her back against the wall, but the curve of her lip told him she wasn’t about to leave it alone.

“Why do you let people assume you’re the lump of dumb meat on Vincent’s elbow?”

“Suits me,” he said, after a long enough pause to let her know she’d overstepped. His own fault for giving her the opening. “You never said: got a better route out of here than kicking the door down?”

“No,” she answered, rubbing her wrists. “I don’t.”

She’d missed the opportunity to really see him move when he’d saved Claude Singapore’s life, and during the previous evening’s skirmish she’d been only peripherally aware of what he did, the phenomenal efficiency and speed with which he’d managed three armed women.

“Farther left,” he said, waving her aside. “Splinters.”

Another time, she might have taken him to task for his lack of deference, but she didn’t want to break his focus, so she edged two more steps away from the door frame and flattened herself against the wall, breathing steadily, ready to spring out and intercept the swinging panel on the rebound. She shielded her face with her hand, but couldn’t resist watching between her fingers as Kusanagi‑Jones took one deep breath.

“If I go down,” she said, “run and keep running.”

He didn’t spare her a glance. “Try not to be the one that goes down.”

Without breaking the steady rhythm of his breathing, he took two fluid steps, spun, and kicked out, hard. The door shattered against the chain, and Lesa kicked off the wall and slung herself through it, catching the rebound on her flat hand. Flesh tore on splintered wood, but she didn’t hesitate.

As she cleared the doorway and broke into a bare, scuffed‑dirt yard, the unwary guard lunged for her and missed. The unshod footsteps behind her were Kusanagi‑Jones’s. She heard the grunt and thud as he slammed into the sentry and hoped Michelangelo had body‑checked him hard enough to break bones.

Not hard enough to shut him up, unfortunately, because he was shouting before he’d picked himself up on his elbows. But Michelangelo was still with her, pulling up beside her, running hard as the camp boiled like a kicked nant’s nest.

Gunfire spattered around her, ended by a curse. Chemical accelerant had a distinctive sound. These were lethal loads, and they came close enough to sting her with kicked‑up earth and splinters. Kusanagi‑Jones grunted as he dropped back a step, falling in behind her, shielding her body with his own.

She wasn’t going to get him shot by running slow. Lesa dodged around the side of a low hut constructed of thatch and daub over a wooden frame and dove past two unarmed males, elbowing the nearer in the jaw as she went by. Judging by the collision, Kusanagi‑Jones took the other one down without breaking stride.

“Go,” Kusanagi‑Jones yelled as she slid around the second corner, between the shelter and the thorn wall. She could see green jungle through the gaps in the canes, and the wall was no more than a meter beyond the hut. His footsteps stopped, his breathing no longer close on her heels.

He was buying her time to get out, turning to make a stand.

Below the edge of the overhang, Lesa bent her knees and jumped. Not for the thorn wall–the long curved spines of wire plant rendered it as impossible to climb as a heap of razors–but for the roof. Her fingers slipped in rain‑slimed thatch, and insects and shreds of vegetation showered her face and shoulders. The top layers were wet, but underneath the fronds were dry–old enough to need replacing–and her hands sank through to latch onto the beam underneath. Wood cracked under her weight, and for a moment she dangled, cursing. Then she got her motion under control, pumped her legs, and half swung, half scrambled up, arms trembling and chest aching with the strain.

This was not a roof built for walking on. She lay flat and turned to pull Kusanagi‑Jones after her.

“Go,” he said, with a glance over his shoulder. He had a weapon in his hands that he must have liberated from the first, unwary guard, and he was bleeding, red dripping from the right sleeve of his gi and spreading over his fingers, more than his torn wrists could explain.

There was no time for thanks, for apologies.

She went.

She slithered across the hunchbacked roof on her belly, turning so she faced the thorn wall, and paused where rafters gave way to the unsupported fringe of thatch. The flat sharp cracks of three more gunshots echoed through the trees, the birds of morning shrieking and then silent. The bullets came nowhere near their position. Encouraging, because the hut wouldn’t offer Kusanagi‑Jones anything except visual cover, but she hoped the partisans might think they were working their way toward the gate.

Kusanagi‑Jones conserved his ammunition, making them find him and thendeal with his ability to shoot back. Smart boy. She’d seriously underestimated the Coalition males.

Lesa clenched her hands around that last flaking roof beam and drew her feet forward into a crouch. It was hard to judge distances in the gray morning light, but she could hear calls through the camp now. Another two or three random shots might serve to raise the alarm for any distant sentries. She stared at the thornbreak one last time, closed her eyes, and jumped for her life.

She might have made it if she could have gotten a running start. As it was, she kicked off hard, stretched, tucked, rolled, and almost cleared the wall. She made it over the top, but the sloped sides were too wide. Thorns tore her shins and forearms, lacerated her shoulders, pierced the hands she raised to shield her eyes and throat. Brittle canes shattered under her weight, and momentum sprawled her clear, lungs emptied, diaphragm aching from the impact.

She gasped and shoved herself up, shaking off bits of twig and barb, driving thorns into her palms and knees as she scrambled to her feet, piercing her unshod soles as she staggered forward through the rubbish. She was leaving a trail of blood and bits a girl could follow, but there was nothing to be done for it now.

Tears and sweat stinging her lacerated face, she ran.

20

ELENA HANDLED KATYA’S ARREST HERSELF. SHE SUMMONED Agnes–a Pretoria cousin who had the same stocky build and epicanthic folds as Lesa–and requested Vincent wait for their return. He was left alone on the sun porch that served as Pretoria house’s center of operations, but deemed it unwise to wander about the house with Elena in the mood he’d put her in. So instead he paced the length of the veranda, reviewing documents on his watch that he already knew by heart.

He’d accomplished everything he’d come here to do–the real reasons, not the surface justifications. He’d met his mother’s opposite number, deemed her honest, established a secure line of communication, exchanged the necessary codes.

Now all he had to do was wrap up two kidnappings, a sabotage operation, a first‑contact situation, a duel to the death, convince Michelangelo he didn’t want to play kamikaze, and figure out exactly how he was going to get rid of the Governors andprotect Ur and New Amazonia from the imperial ambitions of the Coalition. Oh, yes, and at least give his ostensible task–that of reaching some sort of dйtente with whoever was in charge of the New Amazonian government by the end of the week–enough of a lick and a promise that he could justify declaring the mission accomplished and heading home. Or, potentially, blow it so badly that he and Angelo were both discharged in disgrace, which would save him the additional delicate operation of prying Michelangelo loose from the OECC.

Because Michelangelo wascoming home with him.

Just as soon as Vincent reclaimed him.

Piece of cake.

He closed the documents and stood in the darkness, running fingertips along the slick leaves and soft petals garlanding the lattice. A flicker of movement in his fisheye alerted him to company, and he turned his head, but it wasn’t Elena or any of her servants. Instead, a child stood framed in the doorway, pressed close to one of the posts as if he thought he could meld into them. A boy child, nine or ten Old Earth years, six or seven New Amazonian.

Lesa’s son, the one she so desperately wanted to be gentle.

“Hello,” Vincent said.

“Hello,” the boy answered. He came forward a few more steps, from the lighted hallway to the darkness of the porch. “Are you really a diplomat?”

Vincent smiled. The boy–Julian–was hesitant and calm, but the lilt in his voice said he was curious. And Lesa thought he was a genius, and wasted on New Amazonia.