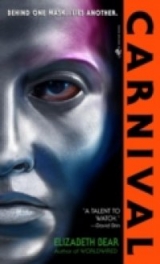

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

It was good.

But it wasn’t what it had been. It couldn’t be; there was too much moving under the surface now, and Kusanagi‑Jones couldn’t set it aside. Vincent was a professional, but he wasn’t a Liar, and he was keeping back something. Once, Kusanagi‑Jones wouldn’t have minded. Once he would have known it was orders, and Vincent would tell him when he should.

But that had been before Kusanagi‑Jones learned just how badly he’d screw Vincent over, when it came down to orders. And not even official orders.

No. Orders on behalf of Free Earth, in opposition to the Cabinet.

Angel walks beside giants. The nearest is warm and smells sour, sweat and fear, but under the scent is the warmth and the familiar spices of home. Mama holds his hand to keep him close, but it isn’t needed; you couldn’t pry him from her side.

Her palm is cold and wet, and her hand is shaking. She calls him On‑hel,like she did, a pretty nickname. She shushes him. They come into a bright room and she picks him up, swings him off his feet and holds him close. Not balanced on her hip, but pressed to her chest, as if she can hide him in the folds of her wardrobe.

Someone says big words, words he doesn’t understand. They boom, amplified. They hurt his ears, and he hides his head in Mama’s breast. She cups a big palm against the back of his head, covering his ears, making the hurt go away. He knows not to cry out loud. He curls up tight.

Mama argues. Her arm around him is tight. But then someone else speaks. He says they won’t take the boy,and Mama staggers, as if someone has struck her a blow, and when he looks up she’s swaying with her eyes closed. “The boy is not to blame,” the man says, the man Angel’s never seen before. “The Governors say, let the punishment fit the crime.”

Then someone pulls Angel away from her, and she lets him go as if her arm has numbed. She turns away, her round brown face contracted. She seems caught midflinch.

He cries her name and reaches for her, but somebody has him, big arms and a confused moment of struggling against strength. He kicks. He’d bite, but whoever has him is wise to that trick. He’s held tight.

“Close your eyes, Angel,” Mama says, but he doesn’t listen. She’s not looking at him. He dreams his name the way she said it again, the fond short form nobody else has ever called him.

Whoever’s holding him says something, some words, but he’s screaming too loud to hear them, and then Mama takes a deep breath and nods, and there’s a pause, long enough that she opens her eyes and turns as if to see why what she was anticipating has not come to pass–

–and she falls apart.

She makes no sound. She doesn’t show pain or even squeak; the Governors are programmed to be humane. But one moment she is whole and alive and letting out a held breath and taking in another one to speak to him, and the next she pitches forward, boneless, her central nervous system disassembled. Within moments, the thing that was Angel’s Mama is a crumbling dune in the middle of a broad white empty floor, and the man who is holding him, too late, thinks to step back and turn Angel’s face away.

He already knows not to cry out loud. He couldn’t, anyway, because his breath won’t move.

The adult holding him soothes him, strokes him, but hesitates when he seems to feel no emotion.

He wasn’t too worried, the adult Kusanagi‑Jones understands. The boy was too young to understand what he’d seen, most likely. And everywhere, there are families that want children and are not permitted to have them.

Someone will take him in.

Angelo’s breathing awoke Vincent in the darkness. It was not slow and deep, but a staccato rhythm that Vincent had almost forgotten in the intervening years, and now remembered as if it were merely hours since the last time he lay down beside Michelangelo.

Angelo was a lucid dreamer. He had learned the trick in self‑defense, with Vincent’s assistance, decades before. Angelo could control his dreams as easily as he controlled his emotions. Just more irony that it turned out not to help the problem.

Because it didn’t stop the nightmares.

Vincent had hoped, half‑consciously, they might have eased over the passing years. But judging from Angelo’s rigid form in the bed, his fists clenched against his chest, his frozen silhouette and panting as if he bit back panicked sobs–

–they were worse.

“Angelo,” he said, and felt the bed rock as Angelo shuddered, caught halfway between REM atonia–the inhibition of movement caused by the shutdown of monoamines in the brain–and waking. “Angelo,”Vincent snapped, bouncing the bed in preference to the dangerous activity of shaking his partner.

Angelo’s eyelids popped open, dark irises gleaming with reflected colors. He gasped and pushed his head back against the pillow, sucking air as if he’d been dreaming of being strangled.

He might have been. All Vincent knew about the nightmares was that they were of things that had happened, or might have happened, and between them they had enough unpleasant memories for a year’s worth of bad dreams.

Vincent put his hand on Angelo’s shoulder; when he breathed out again he seemed calm. “Thank you,” he said. He closed his eyes and swallowed.

“Think nothing of it,” Vincent answered, and put his head down on the pillow again.

Lesa sat cross‑legged on the bed, a cup of tea steaming in her hands, her breakfast untouched on the tray beside her, and watched the Coalition diplomats disentangle themselves from the sheets. She had a parser‑translator running on their coded conversation of the night before, but it hadn’t been able to identify the language. It hadtossed out some possibles, based on cognates, but its inability to provide a complete translation was frustrating. It could put together a word here, a word there–Katherinessen, laughing, calling Kusanagi‑Jones a son‑of‑a‑bitchin plain Ozglish, not even com‑pat–and she got a sense that they were talking about personal history, some old hurt or illness that was tied to the hesitations in their sex.

Just the sort of thing you’d expect recently reunited long‑term lovers to discuss when they were safe under the covers, warm in each other’s arms. But something tugged her attention, something she couldn’t quite call an irregularity, but an…eccentricity. They were together, but strained–by history, she thought, secrets, and maybe the mission itself.

She smiled, watching Katherinessen unwind himself from the bed and pad across the carpetplant to the window, where some delicate tool rested in the sun, dripping tiny solar panels like the black leaves of an unlikely orchid.

Secrets. Of course, Katherinessen waskeeping secrets.

He rested his arm on the window ledge, squinting in the sunlight, and began to fuss with the interface on his implant. Recharging its battery, she realized, after a moment. Clever–and she thought it might have a system to capture the kinetic energy of his body when he moved. Meanwhile Kusanagi‑Jones checked something on his own implant, then stood and glided toward the bathroom. She shook herself free of her urge to watch him go about his morning routine; he wasn’t as pretty as Katherinessen, but he moved like a khir, all coiled muscle and liquid strength. Instead she stood, drank off her tea–kept hot by the mug–and clicked her fingers for Walter. The khir poked its head from the basket beside the door and stretched regally, long scale‑dappled legs flexing nonretractable claws among the carpetplant. Its earfeathers flickered forward and up, trembling like the fronds of a fern, and when it shook itself, dust motes and shreds of fluff scattered into the sunlight like glitter.

Lesa snapped her fingers again and crouched, holding out a piece of her scone. Walter trotted to her, dancing in pleasure at being offered a share of breakfast. It inspected the scone with nostrils and labial pits, then took it daintily between hooked teeth as long as Lesa’s final finger‑joint. She dusted the crumbs off the khir’s facial feathers, and it chirped, dropping more bits on the carpetplant. Standing, its nose was level with hers when she crouched.

She bumped its forehead with her hand, petting for a moment as it leaned into her touch, then stood and walked toward the fresher. The door irised into existence; the shower created itself around her. She hurried. She had things to accomplish before the repatriation, and it wasthe first of Carnival.

Vincent sat on the window ledge, wearing the simplest loose trousers and shirt he had licensed. He sweated under them, the rising sun warming the moist air on his back. His face and chest were cool; his body was breaking the air curtain, but it didn’t seem to disrupt the climate control.

“Angelo,” he called, loud enough to be heard over running water, “do you get the feeling we’re being watched?”

Michelangelo’s voice drifted over splashing. “Expect we wouldn’t be?”

Silly question, sarcastic answer, of course. But there was something picking at the edge of his senses. Something more than the knowledge that there were video and audio motes turned on them every moment. More unsettling than the knowledge that somewhere, a technician was dissecting last night’s lovemaking via infrared and voice‑stress.

Vincent frowned, imagining too vividly the expression on some cold‑handed woman’s face as she analyzed the catch in Michelangelo’s breath when he’d finally consented to thrust up into Vincent with that particular savagery. It was rare that Angelo allowed glimpses of the man under his armor. And Vincent worked for them, he did. He always had.

“Such a gentleman,” he called back as the water cut off, filing the shiver at the nape of his neck under deal with it later. The Penthesileans said their city was haunted, and Vincent did not wonder why. It wasn’t just the wind or the trembling in the walls when you brushed them with your hand.

Sound carried in these arched, airy chambers. Vincent’s first reaction was that they would be prohibitive to heat. Of course, that didn’t mean much at the equator, and they wouldcatch a breeze–but these were people so energy‑rich they let the tropical sunshine splash on their streets and skins unfiltered by solar arrays, like letting gold run molten down the gutters, uncollected.

He thought of Old Earth, her Governors and her painstakingly, ruthlessly balanced ecology, and sighed. If generating power were removed from the equation, that would leave agriculture and resources as the biggest impactors, and a utility fog was a very efficient use of material. One object, transfinite functions.

Michelangelo stepped out of the shower, making it Vincent’s turn. Their wardrobes could handle sweat and body odor, but bacterial growth and skin oil were beyond them. Besides, Vincent had an uneasy suspicion he was getting hooked on warm water flooding over his body. It was a remarkable sensation.

He kissed Michelangelo in passing, and keyed his wardrobe off before he stepped under the shower. Michelangelo would start complaining about the clothes Vincent had chosen for him soon enough, and then, if they hurried, they could make it to the docks and check out the cargo before their command appearance at breakfast and the repatriation ceremony.

“Angelo–” Hot water sluiced across Vincent’s neck, easing discomfort he hadn’t noticed. He checked his chemistry. He could afford an analgesic. And a mild stimulant. Something to tide him over until breakfast, where he hoped there would be coffee.

“Here.” He was in the fresher, his voice pitched soft and echoing slightly off the mirror as if he were leaned in close.

“I need an Advocate.”

Michelangelo’s silence was indulgence.

Vincent listened to the water fall for thirty seconds, and then said, “Kyoto. She never got to say her piece at dinner.”

“The terrifying old battleaxe? What topic?”

“Biological determinism. Can you do it?”

“Right.” Michelangelo cleared his throat. “The only significant natural predator that human women have is heterosexual men. The Amazonian social structure, with its strictures on male activity, has nothing to do with masculine intelligence or capability.”

“Good.” Vincent started to key a toiletry license, and saw a bar of soap resting in a niche in the wall. “Do you suppose this soap is animal fat?”

“Probably,” Michelangelo said, dropping his cheerfully didactic voice of Advocacy. “How’s it smell?”

“Nice.” But Vincent, having sniffed, put it down again and ran his hand under the water until his skin tingled. “So if it’s not that men suffer under reduced capacity, what’s it about?”

“Biology. Self‑defense. Reasonable precautions.”

“Keep going.”

“Traditionally, the responsibility for safety falls on the victim. Women are expected to defend themselves from predators. To act like responsible prey. Limit risks, not take chances. Not to go out alone at night. Not talk to strange men. Rely on their own, presumably domesticated men for protection from other feral men–in exchange for granting them property rights over the women in question.” He laughed. “How’s that?”

“And the New Amazonian system is superior in what way?”

“Punishes the potential predator and arms the potential victim. If men cannot control themselves, control will be instituted. Potential predators are caged, regulated.”

“But?”

Michelangelo fell silent again. Vincent heard the splash of water, the rustle of the towels. “What do I think, or what would Elder Kyoto say?”

“Kyoto.”

“It could have happened centuries ago, but women were soft,” Michelangelo said. “Too soft for revolution. Too willing to believe the best of men. Unwilling to punish all for the sins of many, so they took that onus on themselves, and endured the risks. And a certain percentage of human males acted the way some males of most species will act: infanticide, rape, kidnapping, and the general treatment of females as chattel.”

“And what do youthink?”

More quiet. The water cut off.

Vincent ducked his head out of the shower without rinsing the soap from his hair. “Angelo?”

Michelangelo was leaned against the wall, palms on either side of the mirror, inspecting the whites of his eyes. He turned around and set his backside on the basin between pale‑knuckled hands. “Think we’re all prey. And all predators, given half a chance. What about you?”

After a certain amount of trouble, Kii accesses the spaceship. Timeslip reveals emergent properties; the ship is namedKaiwo Maru, andKaiwo Maru will have been important to the resolution, eventually. The threads lead through her, swirl around her. They are altered when they cross her path, and tumble away in alien directions.

They are altered since the moment she arrived, and Kii understands the implications. This is a cusp. There are others such, that are collapsed. There will have been others again.

The Consent is that Kii examineKaiwo Maru . She uses a simple quantum computing engine, Bose‑Einstein condensates similar to the ones implanted in the encroaching bipeds. She is constructed of modular units, foglets, and is transfinitely adaptable.

And she is aware.

Kii is at first excited to find that she hosts consciousness. There’s more here than Kii has understood; the bipeds are more advanced than Kii could have realized.

But Kii comes to understand that the consciousnesses she hosts are problematic. They are intelligent, focused, with a developed and balanced value system. They are disinterested.

They have only goals and directives, and while they wait for the opportunity to carry out those directives and continue to achieve those goals, they play endless, complicated games.

They find Kii unremarkable. They are incurious.

They are intelligent, Kii decides, notesthelich . They have no art. Which perhaps means the bipeds are notesthelich either, if they are associated with these consciousnesses, which they call the Governors.

If they are notesthelich, not people…

That would simplify things.

7

THE DOCKS WERE TARRED WOOD, AN ARCHAIC EXTRAVAGANCE. Vincent kept wanting to crouch and run his fingers across the surface to verify the size of the logs. They were laid side by side, countertapered, each one meters in diameter at the base. The whole thing shivered faintly when the sea foamed around the pilings. The cargo pod–detached from the lighter, now–bobbed at the end of the pier, squeaking against the bumpers. Vincent was grateful for the hats that Miss Pretoria had had in her hand when she arrived that morning. If he’d been planning on going back to the OECC, he’d have made a note to get them to design licenses for headgear for future diplomats.

Michelangelo stood impassive on his left hand, two steps away and half a step behind. Miss Pretoria was on his right side, her security detail flanking the three of them. They’d taken a surface car here from the government center, a fuel‑cell vehicle. They must use the native power to compress hydrogen for charging it, instead of the processes that had led to such vehicles being banned on Old Earth. There was no tang of combustion products anywhere near the city, and his wardrobe reported clean air. Particulates were limited to dust and organics–skin flakes, pollen, microscopic organisms, the inevitable detritus of man and nature.

Vincent leaned closer to Miss Pretoria and asked, “What will you do when your population increases beyond the capacity of the remnant cities?”

“We haven’t even identified their limits yet. Our problem has been keeping our population on an up‑curve.”

“And yet, no eugenics laws.”

“Women who work historically have fewer children than those who don’t,” she said. “And we work veryhard. Many women get their Obligation out of the way as early as is legal, or don’t even bother with it if they don’t wantto head a household. Three babies isn’t a big investment for a man, but–biologically speaking–it’s an enormous one for a woman. At least until the children are crиched. Also, there’s the Trials. Only our best males breed, and they’re in demand.”

“Stud males,” Vincent said quietly.

Michelangelo glanced at him, and then at Miss Pretoria. “‘Gentle’ males don’t reproduce?”

“There are women who make arrangements. But we won’t stoop to intervention to conceive. And you won’t find a market for implants like yours here.” Her shrug bordered on a shudder.

“Moral objections to implanted tech?”

“After the first Assessment? I don’t know how you can walk around in a utility fog that could start disassembling your body anytime your Governors decide they’re done with you.”

Vincent raised an eyebrow. Michelangelo opened his mouth and shut it again. They walked quietly, the sea breeze ruffling the fine hairs on Vincent’s skin, the pier echoing with the cries of some white‑winged flying animal. Parallel evolution; it looked enough like an Old Earth tern that Michelangelo did a double‑take over the first one, but the rear limbs were feathered as well, and seemed to act as auxiliary wings. Vincent pointedly continued to say nothing when he saw them scavenging among buckets of offal lined up stinking at the quayside.

The reek was astounding. Vincent breathed through his mouth until they were out where the breeze off the bay blew away the worst, and Michelangelo gritted his teeth, swallowed hard, and touched his watch to adjust his blood chemistry. He’s doing that too much. But this wasn’t the time to say it.

The murmur of conversation swelled and dropped as they passed each cluster of bystanders–men and women, finally, although far more of the latter. Vincent stole sideways glances right back. Thesemen were tough looking, muscular, most of them strikingly scarred. They were dressed distinctively, trousers and vests, each of them wearing a leather bracelet on his left wrist with a brightly colored badge. “Household allegiance?” Vincent asked, nodding to the badges.

“License,” Miss Pretoria said.

Vincent bridled at the faint disapproval in her voice. So she doesn’t think they should be out on their own even with a tag in their ears?“For work, or transit?”

“Yes,” she said, eyes forward. “My own–that is to say, the male I plan to take with me when I found my household, when I can buy his contract from my mother–he’s street‑licensed, but doesn’t work. We don’t need the income.” She said it with a certain amount of pride, and Vincent thought of Old Earth men he’d heard say: but my wife doesn’t work, of course.

He shook his head. “These are laborers?”

She nodded as they passed a light security cordon and drew up before the cargo pod. “Usually, they’re of the household that operates the fishing boat.”

The pod had a massive hatchway for unloading, and a tight‑squeeze access port. Both were sealed. A woman standing by in a severe beige suit extended her hand. Vincent surreptitiously keyed his wardrobe to allow contact and met her handshake.

“Miss Ouagadougou,” Pretoria said. “Miss Katherinessen, Miss Kusanagi‑Jones.”

“A pleasure,” Miss Ouagadougou said, winning Vincent’s affection by entirely failing to notice that she was shaking hands with a man.

“Charmed,” Michelangelo said, sounding as if he meant it, and also shook her hand. She was slight and brown‑skinned, with a bit of desk‑job pudge, her gray‑streaked hair twisted into a straggling knot at the nape of her neck. She wore a weapon, just like every woman in Penthesilea, but the leather on the safety strap was cracked as if she didn’t oil or use it often.

“Miss Ouagadougou is one of our leading art historians,” Miss Pretoria said, standing aside. She gestured Vincent toward the sealed hatch on the pod.

He deferred, glancing at Michelangelo. “Angelo’s the expert on the team. I’ve got a layman’s knowledge, but he has a degree in art history from the University of Cairo, on Old Earth.”

Michelangelo’s slight smile reflected amusement as Miss Pretoria blinked at them, obviously conducting an abrupt field rearrangement of her assumptions. “I beg your pardon,” she said. “There’s room for all of us in the capsule.”

“That’s all right. I’ll stay outside.” Vincent folded his arms and pointed with his chin across the water, its serene blue surface transparent enough that he could see rippled golden sand underneath. Penthesilea sprawled and spiked behind him, embraced by the green crescent arms of the bay. In the shadow of his hat, the sun wasn’t even so bad. “It’s a beautiful day.”

Miss Pretoria stared at him for a moment, then nodded. “Don’t wander far. I’d hate to see you kidnapped by pirates. They have an eye for a pretty man.”

“Pirates?” Of course, where there was shipping, there was piracy, but…

“Even New Amazonia has terrorists and renegades,” she said. “By the way, should you have the opportunity to be kidnapped by radicals, you’d rather fall in with the Right Hand Path than with Maenads, if you get the choice.”

Vincent laughed. “I won’t pass the security cordon.” Miss Ouagadougou’s eyes flicked sideways, her lips tightening as if she was about to say something, and Vincent wondered exactly what it might be. Regarding the Right Hand Path, by the timing of her gesture. Michelangelo also shot him a look, and Vincent returned it. Of course I have an ulterior motive. Run with it.

Michelangelo nodded, took the handoff, and turned away, ducking to murmur in the historian’s ear before he produced the key for the cargo pod’s seal. She laughed, bubbling excitement and enthusiasm, almost vibrating with her eagerness to run her gaze over the treasures.

They filed inside, leaving the door open, and Vincent sighed in an unanticipated intensity of relief. Alone at last,he thought, self‑mocking, and leaned against a piling, tilting his hat forward to produce a little more shade. To anyone observing, he might have seemed to be drowsing in the sun, halfheartedly watching the bustle the length of the pier.

He wasn’t surprised to see a man he recognized from the reception round the pilings at the land end of the pier and walk up the path between bustling fisherwomen, obviously intent on the cargo pod. The man was dressed like the laborers, although his trousers and vest were of better quality, embroidered, and the badge on his left wrist looked more elaborately decorated. His shaven head gleamed black as basalt under the heat of the sun, and he was big and fit, but none of that was unusual. Neither the scars pale against his complexion nor the swagger in his stride set him apart among Penthesilean men.

What startled Vincent was the man’s companion; a leggy teal‑green‑and‑gold‑dappled animal, maybe sixty kilos, all long bones and prancing angles under the windblown fuzziness of what was either a pelt or hairlike feathers. One of the raptor‑creatures from the Dragon’s frieze, it looked more predatory in the flesh. Two large front‑facing eyes would provide binocular hunter’s vision, sheltered under fluffy projecting eyebrows. Something like a moth’s fronded antennae protruded from the top of its long head, and its limbs, muzzle, and belly were scaled, a sleek contrast to the warm‑looking fluff on its back.

“Pets,” Vincent said, under his breath, watching the way the beast leaned its shoulder on the man’s thigh as they moved down the pier. “They have pets.”

Well, of course. They ate animal flesh, and while some of it must be harvested from the wild–witness the bustle and the stench of death on this pier–they also must have domestic animals. And it was a short step from one perversion to another, from enslaving animals for their meat to enslaving them as toys.

Vincent kept his face carefully calm in the dappled shade of his hat, and swallowed to fight the taste of bile.

And this is better than the Governors?The beast nosed the man’s hand as they paused by the security cordon and the man rewarded it with a quick ruffle of its feathers. It was like watching a grown man in diapers; the process of infantilization was complete. There was no way an animal so crippled could have a life outside of human control.

This is what we are when we’re left to our own devices–savage, selfish, short‑sighted.Vincent squared his shoulders, thought of Michelangelo, and frowned. But free. Any government founded on a political or religious agenda more elaborate than “protect the weak, temper the strong” is doomed to tyranny,he quoted silently, and made himself look away from the tame animal. He slipped an etched‑carbon data chip no larger than his thumbnail out of his pocket and concealed it in his lightly sweating palm. It was steady‑state material, not a fog, and fiendishly expensive, but there were too many security risks entailed in using his watch to transport data as sensitive as this. And he could afford it with his mother footing the bill.

They’d have to make the trade quickly, invisibly, without detection by the security agents, Michelangelo, or Miss Pretoria. The New Amazonian habit of indiscriminate handshaking proved itself useful for once.

Vincent checked his watch as the black‑skinned stranger showed the security guards his license, displayed a data pad of archaic design, and was waved through. No doubt, he was ferrying a message for Miss Pretoria or Miss Ouagadougou.

Eight hundred hours, as arranged.

Right on time.

Lesa hung back by the hatch, inside the cool darkness of the shuttle, and watched Nkechi Ouagadougou and Michelangelo Kusanagi‑Jones code‑key open cargo lockers with the sort of reverence she associated with wrapping a funeral shroud. Lesa herself wasn’t an artist or a scientist. Her aesthetic sense was limited. If it weren’t for her empathic gift, if her foremothers hadn’t had the resources for Diaspora and she’d been born on Earth, she’d have been Assessed.

But as Ouagadougou and Kusanagi‑Jones paused before each freshly opened chamber and waited for the utility fog that served as packing material to fade to transparency, she could feel their awe. It rolled off them in bittersweet cataracts, Kusanagi‑Jones’s flavored with a faint reluctance and Ouagadougou’s dripping eagerness. It was a held‑breath sort of moment for both of them, and Lesa didn’t want to intervene.

Besides, enjoyable as the overflow of their quiet glee was, she was only pretending to watch them. Practically speaking, she was watching Katherinessen. And Robert, who paused beside the step up to the door to introduce himself. They shook hands–Lesa’s smile never showed–and Katherinessen’s hand slipped back into his pocket. “They’re inside,” he said. Quietly, but his voice was crisp enough to carry.

Robert bowed, his manners impeccable, and glanced at the hatch. Lesa knew she was invisible in the darkness within. She stepped forward so the light would catch on her cheekbones and held out her hand. “Hello, dear.”

He didn’t step inside the pod, just held out a datacart and bowed as she accepted it. Something else fell into her palm–a chip, which had been pinned between his thumb and the cart. She flipped her hand over, opening the cart. “Anything important?”

He looked demure, or a convincing approximation. “Elder Elena Pretoria sends her regards,” he said, folding his hands behind his back. “And requests her daughter inquire as to whether the emissaries would consent to join the household for supper and Carnival tonight in the absence of other plans.”

Lesa thumbed the cart and slipped the chip into her pocket casually with the opposite hand. “All I can do is ask.”

Michelangelo swung down from the pod in a state of elation, feeling light and taut enough that he actually checked his chemistry to make sure it wasn’t a malfunction. The twin expressions of concern that Vincent and Miss Pretoria wore stopped him short before he was firmly grounded. His foot skipped on the wood underfoot, and he reached up and tilted his borrowed hat to cut the glare.

“Problem.” His eyes were on Vincent, but it was Miss Pretoria who answered.

“A small one,” she confirmed, and moved forward with one hand upraised to stop Miss Ouagadougou from running into Kusanagi‑Jones’s back. Which was fortunate. Kusanagi‑Jones was not looking forward to apologizing to the first unwary New Amazonian who bounced off his wardrobe or was shocked by it…but he also wasn’t about to dial the safety features down unless he was actively engaged in shaking someone’s hand.