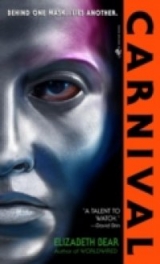

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

And now, finally, he heard thunder and a distant pattering like dry rice shaken in a container that might be the sound of leaves brushed aside by rain. The jungle was big and disorienting, full of things to trip over and ground too soft to run on without twisting your ankle, the trees teeming with flickering animals, black birds with feathered hind‑limbs that they used like a second pair of wings and screaming green‑feathered lemurs with bright, blinking eyes.

Too late,he told himself as he gathered himself to touch her, bracing for disappointment, taking in the seeping, swollen lumps of her feet, the glossiness of the infected scratches on her hands. He could kill without hesitation, but it took him seconds to gather the courage to reach out and push her matted hair away from her face.

Warm.

Of course, she would be. The air was hotter than his skin. She didn’t stir, and he reached to brush her hair back, to afford her whatever privacy in death he could.

But something caught his attention and held it, and he heard himself bringing in a slow, thoughtful breath, full of the scents of blood and infection and the warm sweet yeasty smell of the moss and the fermenting earth.

Her eyes were closed. Closed all the way, closed softly and completely, the way a dead woman’s eyes would not be.

He grabbed her wrists and dragged her huddled body out from under the curve of the root, laying her flat on her back as rain began to patter on the leaves overhead, not penetrating the canopy at first but then pounding down, splashing his face, soaking a dead man’s shirt, washing the grime and sap and blood off the deep angry scratches on Lesa’s face.

Kusanagi‑Jones leaned back on his heels, gathered Lesa up in his arms so the water wouldn’t pound up her nose, and tilted his own face to the warm rain, mouth open, feeling her heart beat slowly against his chest.

She awoke fifteen minutes later, while he was dragging her into a hastily constructed shelter, rain still smacking their heads. The first thing she did when she blinked fevered eyes and saw him bent over, half carrying and half‑shoving her under a badly thatched lean‑to, was start to laugh.

“One thing I never understood,” Lesa said, rainwater dripping down the back of her neck. “Why the Coalition is so set against gentle males–”

“What’s not to understand?” Michelangelo might seem brusque and hardhanded, sarcastic and cold, but he touched her damaged skin with exquisite care. He’d gotten a medical kit somewhere, and a shirt he was tearing into bandages. Whatever he was doing made her feet hurt less. Which wasn’t surprising; her ankles looked like the trunks of unhealthy trees, and could hardly have hurt more.

He had started at the soles of her feet, mummifying her from toes to ankles, and was now dabbing the red, swollen bites on her calves.

“It’s not like you contribute to population growth,” she said, frowning. He pressed the sides of a bite, clear fluid seeping between his fingertips. “Ow!”

“Sorry.” He smeared that wound, too, glossy leaves dimpling and catching under his knees as his weight shifted. The motion tumbled another scatter of rain down Lesa’s neck, and a few jeweled drops made minute lenses on his close‑cropped cap of hair. “No, it’s not. Not by accident, anyway.”

“But?”

“You’re operating on spurious assumptions, so your conclusions are flawed.”

“How–Ow! How so?”

“One, that sexual preferences have anything to do with reproduction. Doesn’t matter who you fuck. Only way to have an unauthorized baby on Earth is to plan it.” His hands shook as he tucked in a stray end of bandage, and she thought, startled, that he wasn’t lying to her now.

“Two?” she pressed, when he’d been silent a little longer.

“Human societies aren’t logical. Yours isn’t. Mine isn’t. Vincent–” He coughed, or laughed, and shook dripping water out of his hair. “–well, his is at least humane in its illogicality.”

“So why?”

“You want my theory? Worth what you pay for it.”

She nodded. He looked away.

“Cultural hegemony is based on conformity,” he said, after a pause long enough that she had expected to go unanswered. “Siege mentality. Look at oppressed philosophies, religions–or religions that cast themselves as oppressed to encourage that kind of defensiveness. Logic has no pull. What the lizard brain wants, the monkey brain justifies, and when things are scary, anything different is the enemy. Can come up with a hundred pseudological reasons why, but they all boil down to one thing: if you aren’t one of us, you’re one of them.” He shrugged roughly into her silence. “I’m one of them.”

“But you worked for…‘us.’”

“In appearance.” He reached for another strip of cloth.

It was damp, but so was everything. She shivered when he laid it over seeping flesh. “How long have you been a double?”

The slow smile he turned on her when he looked up from the work of bandaging her legs might, she thought, be the first honest expression she’d ever seen cross his face. He let it linger on her for a moment, then glanced down again.

“I can tell you one way your society does make sense,” Lesa said. “The reason Old Earth women don’t work.”

“And New Amazonian men? But some do. Not everyone can afford the luxury of staying home.”

“Luxury? Don’t you think it’s a trap for some people?”

“Like Julian?” Harshly, though his hands stayed considerate.

She winced. “Yes.”

The silence stretched while he tore cloth. She leaned against rough bark. At least her back was mostly unbitten. “During the Diaspora,” Lesa said, “there wasn’t workon Old Earth. Industry failed, demand fell, money was worth nothing. The only focus was on getting off‑planet. Then, after the Vigil, after the Second Assessment, when the population stabilized, there was an artificial surplus of stuff left over from before. The Old Earth economy relies on maintaining that labor shortage. So women’s value to society is not as professionals, but as homemakers or low‑paid labor. And then you fetishize motherhood, and tell them that they aren’t all good enough for that…”

She trailed off, looking down to see what he was doing to her legs. More salve, more bandages. Meticulous care, up to her knees now. That was the worst of it.

“The Governors’ engineers were mostly female,” Michelangelo said, as if to fill up her silence. “Seemed like a good idea at the time.”

“And Vincent didn’t know about your sympathies?”

“To Free Earth? He didn’t. Not the sort of thing you share. If I wind these, it’ll make it hard to walk.”

“Just salve,” she decided, regretfully. The pressure of the wraps made the bites feel better. “He knows now, though.”

“We both know. Delicious, isn’t it?”

She’d never understand how he said that without the slightest trace of bitterness. “So you grew up gentle on Old Earth, and you became a revolutionary.”

“Never said they were linked.”

“I can speculate.” She touched his shoulder. His nonfunctional wardrobe couldn’t spark her hand away.

He tucked the last tail of the bandages in, and handed her the lotion so she could dab it on the scattered bites higher on her legs, her thighs and belly and hands. He sat back, and shrugged. “It’s not common. Maybe 4 percent, baseline, and they do genetic surgery. Mostly not an issue to manage homosexual tendencies before birth. In boys. Girls are trickier.”

His tone made her flinch.

“Did I hurt you?”

“No,” she said. “Just…genetic surgery. You’re so casual.”

“As casual as you are about eating animals?”

It wasn’t a comment she could answer. “And your mom didn’t opt for the surgery?”

“My mother,” he said, sitting back on his heels as the imperturbable wall slid closed again, “planned an unauthorized pregnancy. And concealed it. I wasn’t diagnosed prenatally. And I don’t think anybody expected me to make it to majority without being Assessed.”

“And you weren’t.”

“No,” he said, quietly. “She was.”

This time, when he touched her ankle, she shivered. But not because of him. She covered his hand with her own, leaning forward to do it, breaking open the crusted cuts on her palm and not caring. “I’m glad you weren’t,” she said. And then she leaned back against the smooth gray aerial root of the big rubbermaid tree that formed the beam and one wall of the lean‑to, and slowly, definitely, closed her eyes.

23

VINCENT COULD SEE NOTHING FROM THE AIR, BUT THAT failed to surprise him. He perched on the observer’s seat of the aircar, beside the pilot, and made sure his wardrobe was active and primed. The Penthesileans wouldn’t give him a weapon, but as long as he had his wits, he wasn’t helpless.

A weaponized utility fog didn’t hurt either.

“They must have a camouflage screen up,” he said over his shoulder.

Elena, in the backseat, grunted as the aircar circled. “Or Katya lied to us.”

“Also possible,” Vincent admitted, as the pilot reported finding nothing on infrared. “I don’t suppose any of these vehicles have pulse capability.”

“This one does,” the pilot answered, after a glance to Elena for permission.

There were seven aircars in the caravan, armored vehicles provided by Elder Kyoto through the Security Directorate. According to Katya, that should be more than enough to handle the complement of this particular Right Hand outpost.

And again, Katya might be wrong. Or she might be decoying them into a trap, though Vincent’s own skills and instincts told him shebelieved she was telling the truth.

Of course, he’d also trusted his own skills and instincts about Michelangelo. But Angelo was the best Liar in the business–and close enough in Vincent’s affections that any reading would be suspect anyway.

“Take us higher, please,” Vincent said. The pilot gave him a dubious look, but when Elena didn’t intervene she shrugged and brought them up. Somewhere down there, indistinguishable from the rest of the canopy by Gorgon‑light, had to be the camouflage field. Invisible–but not unlocatable.

Vincent’s wardrobe included licenses for dozens of useful implements, among them an echolocator. It was designed for use in situations where there was no available light and generating more would be unwise. In this case, he was obligated to patch through the aircar’s ventilation systems to externalize the tympanic membranes, but that was the work of a few moments.

The readout projected to his implants was many‑edged, shifting, translucent, but perfectly detailed, each individual leaf and branch discernable over the spongy reflection of the litter‑covered ground. And just off to the south was a gap in the fragile, shadowy echoes of the canopy, a mysterious, rough‑edged hole floored with sharp regular echoes and softer elevated patches.

“There,” Vincent said, and pointed. “South by southeast, 40 degrees descent.”

“It’s all trees,” the pilot said, and Vincent frowned at her–the frown he reserved for people who obviously couldn’t have meant to disappoint him, and so must have done it through some oversight. “It’s a utility fog,” he said. “A limited‑license one. It pattern‑matches the surrounding territory. Look, see that tree?”

There was one, in particular, a bit taller than the rest and a bit paler in color, as if it hadn’t entirely leafed out yet or were growing in iron‑poor soil.

The pilot nodded. Elena leaned over the chair back to see better, laying a possessive hand on Vincent’s shoulder.

“There’s another one,” she said, and pointed left. The angle was different, and so the silhouettes didn’t quite match, but there they were, as alike as if cloned. “Which is real?”

Vincent indicated the second one with a jerk of his thumb, making an effort not to shrug her hand away, no matter how it irritated. Andreminded him of the tenderness of peeling skin.

At least the damned sunburn hurt less than it had and his wardrobe was doing an adequate job of coping with the sloughing epidermis. Which was unpleasant. But, by comparison, didn’t hurt enough to be worthy of the term.

“Is it safe to descend through the canopy?”

He hesitated. “Theoretically.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning it’s a utility fog, and they can be weaponized. Elder Pretoria–”

Her hand flexed on his shoulder. He hid a flinch. “Yes, Vincent?”

Not Miss Katherinessenanymore. “Does anybody on New Amazonia use fog technology? Because something Lesa said led me to believe it wasn’t warmly considered–”

“No,” Elena said. “They don’t.”

He nodded. “Then I can’t guarantee what we’ll run into.”

“Right,” she said, and released him. “Jayne?”

“Elder Pretoria?”

“Bring us down onto the canopy, would you? And let the others know what we’re doing, and why.”

The aircar didn’t have the flexibility of programmable vehicles that Vincent was used to, but he had to admit that the landing nets were impressive. Jointed insectile limbs unfolded, stretching glistening mesh between them, and the aircar settled onto a forest canopy made mysterious by nebula‑light. The trees dimpled and groaned under the distributed weight, and Vincent heard wood creak and twigs snap wetly, but they bore up under the weight. On each side, the other aircars settled into the canopy, surrounding the camouflaged clearing, pastel swirls of night sky reflected in their glossy carapaces so they looked like enormous, jeweled beetles resting on spinners’ webs.

“How do we get out?” he asked, because he knew it was expected of him.

And Elena smiled, ducked down, folded the center rear seat up, and tugged open a hatch in the floor.

The camp was deserted, which surprised Vincent even less than its invisibility. The security personnel had body armor, weapons, metal detectors, and khir trained to sniff for explosives and hidden people, and he was content to let them conduct the search. He stuck close to Elena and to Antonia Kyoto, who had arrived in a separate car, and eavesdropped on incoming reports with their complicity.

It took them less than half an hour to secure the camp, which showed signs of having been abandoned with great haste and insufficient discipline. Supplies had not been taken, and one of Kyoto’s people uncovered a cache of weapons under a bed in one of the ten or eleven huts clustered within the zareba.

It was Shafaqat Delhi who found Robert Pretoria’s body, though, and hurried back into the camp to inform Vincent and Elena–and then had to jog to keep up with him on the way back out, while Elena followed more sedately.

Somebody had rolled Robert over, but that wasn’t how it had fallen. Vincent crouched beside crushed greenery and traced the outline of the body in the loam, running fingers along the deeper, smoother imprint where someone had shoved Robert’s chest into the ground while he broke his neck.

Vincent turned and ran his fingertips across the base of Robert’s skull, below the occiput. The distended softness of a swelling met his fingertips, exactly where he expected.

“Vincent?”

“Blow to the head,” he said, wiping his hands on Robert’s shirt before he stood. The dead man’s pockets had been rifled, and any gear he had with him taken, and the leaf litter in the area of the body was roughed up as if from a scuffle.

There hadn’t been any scuffle. He’d been as good as dead the minute he turned his back.

Vincent stood, his feet where Angelo’s feet would have been when he struck, and turned a slow pirouette. And there it was, exactly at a height to catch his eye. A single hair, black and tightly coiled, snagged in the rough bark of a tree about four meters from the murder scene.

It could have been Robert’s hair, if his head wasn’t shaved. But it wasn’t.

Vincent covered the distance in three long steps and stopped. The forest floor was undisturbed, leaves and sticks and bits of moss exactly as they should be. He crouched again, feeling alongside the roots of the trees, combing through the litter with his fingertips. Worm‑eaten nuts, curled crisp leaves, sticks and bits of things he couldn’t identify–

–something smooth and warm.

His fingers recognized the datacart before he unearthed it, although Michelangelo had wrapped it in a scrap torn from a dirty shirt. Vincent brushed it carefully clean, aware that Shafaqat and Elena were watching him in breathless anticipation. A sense of the dramatic made him hold his silence until he could turn, drop one knee to the ground to brace himself, and raise the datacart into their line of sight before he powered it on. There was a password, but Vincent could have entered it in his sleep.

He had been meant to guess it.

It didn’t beep. Somebody had disabled that function. But it did load something: a glowing electronic image of green and golden contour lines and insistently blinking dots.

“What’s that?” Shafaqat asked.

Elena put one hand out, pressing her palm to the bole of a tree to steady herself, and sighed as if she could put all her pain and worry onto the wind and let it be carried away. “A scavenger map,” she said. And then she stood up straight and rolled her shoulders back. “Come along, Miss Delhi, Miss Katherinessen. No rest for the wicked yet.”

Even by Kusanagi‑Jones’s standards, it was a pretty cinematic rescue. He awoke from a fitful doze at dawn, when a frenzy of animal cries greeted half a dozen digital‑camouflage‑clad New Amazonian commandos rappelling through the canopy. They landed in the glade where Lesa had been half‑crucified on the thorn vines and unclipped, fanning out with polished professionalism. Half a dozen commandos–and Vincent, dapper and pressed and shiny‑booted as always, handling the abseiling gear as if he spent every Saturday swinging from the belly of an ornithopter.

Kusanagi‑Jones rolled onto his back and reached out to nudge Lesa awake, but she was already propped up on one elbow, peering over his shoulder. Her face, if anything, looked more lined with tiredness than it had the night before, and more of her scratches were inflamed, but the smile curving her lips was one of relief. “Come on,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, holding out his hand. “I’ll carry you down there.”

“Fuck that,” she answered. “I’ll walk.”

And she did, or hobbled, anyway, leaning on his elbow harder than either of them let on.

Kusanagi‑Jones didn’t even really mind when the first thing Vincent did was hug him hard enough that it knocked him back a step. Especially when the second thing he did was piggyback their watches together, and give Kusanagi‑Jones’s wardrobe a kick start and a recharge to baseline functional levels.

Later, after the medics had seen to his injuries, and while he was still tucked into bed hydrating on an IV while they worked on Lesa’s more serious wounds, Vincent brought him a tray, and spread jam on crackers for him to eat. They sat silently, shoulder to shoulder. Kusanagi‑Jones had edged over to make room, and Vincent leaned against the headboard with one foot on the floor and one propped up on the bed.

“Can’t go home yet,” Kusanagi‑Jones said at last, over their private channel, when it became evident that Vincent wasn’t going to bring it up.

“No,” Vincent answered, after letting the statement hang for a bit. And then he said out loud, “Eat the soup. It’s good.”

“I hate lentils.” But he ate it, thick and pasty and full of garlic, and it was better than he expected. He needed the protein, anyway. And the salt. “There’s Claude to deal with.”

“There is,” Vincent admitted, “still a negotiation to complete. And a duel to fight if we can’t find that lab, and link Singapore and Austin to it.”

Kusanagi‑Jones glanced down at his watch. Every light shone clean and green, except the blinking yellow letting him know fatigue toxins were building to the point where chemistry wasn’t cutting it anymore. He held it up so Vincent could see. “There’s also this.”

“You know what I think,” Vincent answered, his voice chilly and flat. Kusanagi‑Jones reached out and curved his fingers around Vincent’s wrist, and Vincent didn’t shake him off.

Kusanagi‑Jones couldn’t remember how he’d ever decided anything on his own. Maybe he hadn’t. Maybe he’d just done what other people told him. “What are we going to do?”

Vincent shrugged to hide his shudder, and pushed another cracker in front of Kusanagi‑Jones.

“There are no limits to brane technology,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, ignoring the cracker.

Vincent slid off the bed, but gently, and moved away. There was a window in the room, shaded by louvers that broke the tropical sunlight into bars. He stood before it and laced his hands behind his back. “Once there were no limits to what you could discover with a sailing ship.”

“False analogy–”

“Fine. It’s false. What’s the moral implication of the damage we do to the planets we colonize? What about gravity pollution,for the Christ’s sake? Can you even begin to come up with a list of potential ill effects? Black holes? Supernovae? Planetary orbits? It’s not a clean technology. It just pollutes in ways we can’t begin to cope with.”

“Are no clean technologies,” Kusanagi‑Jones reminded.

Vincent continued as if he hadn’t said a word. “What if we expand into species less companionable than the Dragons? There’s a lot of what‑ifs.”

“Do what we’ve always done,” Michelangelo said. “Trust the next generation to solve their problems the way we’ve solved ours. Risk is risk. We live with it.”

“By hitting the cosmic reset button one more time. That’s a technical solution to an ethical problem. Hell, it’s not even a solution–it’s a delaying action. That’s what got us into this situation in the first place.”

“Entropy,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, “is a bitch. There’s still the retrovirus–”

“Angelo, I will shoot you myself.”

Their eyes met. Vincent wasn’t a Liar. He meant every word. “All right,” Kusanagi‑Jones said. “There isn’t the retrovirus.”

“There’s another solution,” Vincent said coolly, although the pit of Kusanagi‑Jones’s own stomach lurched when he realized what his partner meant. “We leave the Governors in place.”

“No!”

“Yes,” Vincent said. “Listen to me. There’s magic in it. Because once we learn to control ourselves–”

“Oh, no. Vincent, you are not sayingthis.”

“–the Governors become obsolete. On their own. If we clean up after ourselves, Angelo, they have no reason to intervene.” Vincent let his hands fall and squeezed them into fists, as Kusanagi‑Jones squeezed back against the headboard, as if he could crowd himself into the wall and somehow get away.

“Then we all die in a fucking Colonial revolt. You, me, your mother, Lesa, Elena. For a bunch of geniuses, you’re all idiots for thinking you can stand up to the Coalition.”

“New Earth stood up.”

“New Earth had help. And even if the Governors wouldn’t permit an open Coalition intervention, how many New Earthers do you suppose died in the covert retaliations for what I did to Skidbladnir? Wasn’t me that paid that price.”

Vincent’s answering silence was long. “The Dragons?”

“Might defend the New Amazonians. Not Ur. And this is the human society you want to protect? I don’t think so.”

He could hear Vincent breathing. He wondered if he knew what Kusanagi‑Jones was about to say. Kusanagi‑Jones, his eyes shut, rubbed his knuckles across his face.

His voice dropped. “Consent.”

Vincent’s flat expression, when Michelangelo opened his eyes again, seemed an attempt to convince himself that he hadn’t actually understood. Kusanagi‑Jones’s face felt numb.

He kept talking.

“Kii won’t give us the brane tech. What if we offer him another way out of a war? He’s ethical. We offer Kii the opportunity to engineer a virus that modifies the human genome, that inducesConsent, and we get the fucker to downgrade self‑interest as a motivating force.”

“The Christ,” Vincent whispered. They stared at each other.

“Vincent. This is…this has to be exactly–”

Vincent’s larynx bobbed as he swallowed, a shadow dipping in the hollow of his throat. “They were the first ones to die, you know. You can’t accuse them of hypocrisy. The Governors Assessed their creators first.”

“Cowards,” Michelangelo said. He shoved the tray aside and swung his feet out of bed, wincing as blistered flesh contacted the tiled floor. “Cowards who didn’t want to watch their program carried out. Could cause a genocide, but couldn’t stand to live through it.”

“This is just how they felt.”

“Heady, isn’t it?”

“Angelo–”

“No. Don’t argue. Think. What do you have that’s better?”

“Who are we to choose for an entire species?”

Michelangelo gave Vincent his sweetest smile. “Who better?”

Vincent backed up to lean against the wall and folded his arms. “Every solution is going to present us with new problems down the line. And this would put an end to Lesa’s problem, too. The way to stop men from preying on women without treating the entire sex as criminals is simply to remove the predatory urge. If we can’t be trained, we can be broken.”

“You’re Advocating.”

Vincent winked, but Kusanagi‑Jones saw his hand shake when he checked his chemistry, taking a moment to revise the adrenaline load down to something manageable. “All right. I’ll Advocate. I’m Lesa. She would say it was immoral to tamper with human biology, and more defensible to institute social controls to the same effect.”

“So slavery is more moral than engineering out aggression.”

“It’s not chattel slavery.”

“No,” Kusanagi‑Jones said. “An extreme sort of second‑class citizenship.”

“Not much worse than women in the Coalition.”

“Women in the Coalition can vote, can work–”

“Can be elected to the government.”

“Theoretically.”

“Practically?”

“Doesn’t happen.” Kusanagi‑Jones swallowed. “Who’d want a woman in charge?” Except on some of the repatriated worlds. But Ur was the only one with the nerve to send a woman to the Cabinet. The conviction had dropped from his voice. “I can’t even Advocate this anymore, Vincent. It’s just wrong.”

“No fanatic like a new fanatic,” Vincent said. He came to Kusanagi‑Jones and crouched beside him, and patted him on the knee. “We’ll figure something out.”

“Scared,” Michelangelo said, a raw admission meant as much for himself as for Vincent.

And Vincent knew it. Michelangelo could tell by his expression, the arched eyebrows, the line between them. “Having your preconceptions rattled is unsettling.”

“No,” Michelangelo said. He dropped his face to his hands, pushed fingertips against his eyelids until the pressure hurt. The pain didn’t help his focus, so he dropped his hands and looked up instead. “Scared we’ve already figured it out.”

Vincent stood, all lithe grace, and let his hand rest warmly on Michelangelo’s shoulder. “Whatever,” he said. “Let’s at least talk to Kii about getting that weapon cleaned out of your bloodstream, shall we?”

Michelangelo nodded. “And then tell Lesa about Kii, and see what shebloody thinks.”

Vincent and Michelangelo found Lesa on Elena’s beloved veranda, her bandaged feet propped on the softest available cushion, a plate on her lap and a sweating glass beside her as she watched Julian and some other children romp in the courtyard with a couple of khir. Vincent didn’t think Elena would have left her alone willingly. It must have taken a spectacular temper tantrum.

She didn’t acknowledge them at first, as he and Angelo came up beside her–unescorted–and took places on a wooden bench. It was polished smooth, the wood warm in the muggy afternoon, and Vincent leaned forward with his elbows on his knees, watching in fascinated horror as Lesa worked her way around a piece of shellfish sushi rather like a snake ingesting a too‑large mouse: lingeringly and with many pauses.

“I’m sorry about Robert,” Angelo said finally when the silence had gone on longer than Vincent expected.

Lesa didn’t look. “I’m not,” she said. “But don’t let Katya find out about it, okay?”

Vincent felt Michelangelo shrug. “I won’t.”

She did turn, then, and give them a painfully dilute smile. “I’ve just heard from Antonia Kyoto. She wanted me to pass along her thanks for your information as well, Michelangelo. And let you know that Miss Ouagadougou and Stefan have been arrested. And are under…considerable pressure to name the rest of the Right Hand apparatus.”

He grunted. “Miss Ouagadougou wasn’t working for the Right Hand,” he said. “She’s Coalition.”

“Yes,” Lesa said. “Antonia just led a raid on another encampment and found more Coalition tech. It might save us an insurrection if we can find enough of them.”

Vincent said, “And Katya?”

“She’ll go to prison.” Lesa said it so calmly that Vincent looked at her twice. The tension lines around her eyes told another story. “But she’s young. And it won’t be forever.”

Vincent had no answer. He leaned on Michelangelo and didn’t try to come up with one.

Lesa cleared her throat. “And I also heard from Claude.”

“And?”

“She wants to set the duel for the sixth of Carnival.”

Vincent glanced doubtfully at Angelo, but Angelo’s gaze was on the children in the yard. “Three days. Will you be able to walk by then?”

That homeopathic smile didn’t flicker. She picked up another piece of sushi and contemplated it before she said, “I don’t need to walk to shoot somebody, Vincent.”

“And are you as fast today as you were the other afternoon?”

She didn’t answer, and he thought about her silence while she chewed. Angelo shifted on the bench, leaning closer while Vincent pretended not to notice. Funny how he could always tell exactly where Michelangelo’s attention was, even when Angelo was pretending it was somewhere else.

“We need to find that lab. Then there won’t be a duel.”

Too late, he remembered she didn’t have the context, and was opening his mouth to explain when she silenced him with a wave. “Mother told me.”

“I thought she would.”

“And I told Antonia,” she continued. Vincent opened his mouth, and she silenced him with one raised finger and a chipped stone glare. “If I don’t live through the duel, she needs to know what Claude is capable of.”

Vincent didn’t answer, but he swallowed and nodded. All right.

Lesa turned to Angelo. “Are you going to get the infection taken care of? Canyou get it taken care of?” She spoke to Michelangelo rather than Vincent, but Michelangelo didn’t look at her.

“We can,” Vincent said. “And will. Which reminds me. There’s somebody we want you to meet.”

“Where?”

“Inside.”

“Hand me my crutches.”

Michelangelo was still at his shoulder when they came into the house, following the stubborn staccato of Lesa’s crutches. She managed them well, stumping forward grimly–though she winced when her weight hit her hands. Thick batting padded the handles; it obviously wasn’t enough.