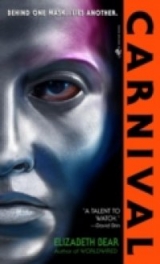

Текст книги "Carnival"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

Соавторы: Elizabeth Bear

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

“Who wants in on the conspiracy.”

“She’s in,” Vincent replied. Kusanagi‑Jones gave him the dirtiest look he could manage, and Vincent met it bold‑faced.

“Nice private little junta you’ve whipped up.”

“It’s what you call an arrangement of convenience,” Vincent said. “The bad news is, Robert is missing–”

“And Robert knows about all three of you.”

“And my mother,” Lesa said. “Who is not, however, aware that we’re hoping to rearrange New Amazonia’s social order quite as much as we are.”

“And it’s safe to talk about this in her house?”

Lesa smiled. “My security priorities are higher than hers.”

Vincent straightened, moving stiffly. “Ur’s prepared to go to war, if necessary. This doesn’t have to stay secret long.”

Kusanagi‑Jones shook his head. He suspected that if he were even remotely psychologically normal, he shouldhave been feeling worry, even panic. But it was excitement that gripped him, finally, the narrow color‑brightening focus of a purpose. “I’ve hopped a cresting wave.”

Vincent smiled. “Something like that. We’re committing treason against two governments; everybody with a grudge can ride. Do you think your Free Earth contacts can help?”

“Depends what the plan is.”

“What was yours?”

“Sabotage. Prevent Earth from getting its hands on the technology by any means necessary. Very straightforward. Easy enough for a lone operative to accomplish.”

Lesa looked up. “What made you go to Vincent, then?”

“Vincent knows. He’s satisfied.” Well, he knew the hasty outline at least, Kusanagi‑Jones having filled him in quickly about Kii’s ultimatum before they decided to bring the challenge to Miss Pretoria’s attention. Hadn’t been time for details.

“Anyway,” Kusanagi‑Jones continued, when Lesa had been staring at him for a little longer than was comfortable. “How many factions arethere in the New Amazonian government?”

“That I’m aware of?” She shrugged, too. “For current players, we have to count all of us, Parity, whoever Robert is working for, the isolationists, the appeasement faction, and the separatists, who want the males– allthe males–off New Amazonia. And whoever it was who tried to kidnap Vincent, whoever attempted to assassinate Claude–”

“Though there may be overlap.” Vincent made a face. “Do we at least have a DNA type on that woman you wounded yesterday?”

“Take at least a week,” she said, and Kusanagi‑Jones wasn’t sure if he or Vincent looked more startled. “Backwater colony, remember? As you were so eager to point out to us just the other night. Besides, genetic research is a very touchy subject here.”

A pained silence followed. Vincent cleared his throat. “Anyway, our plan was a little more complex.”

“It always is.” But Kusanagi‑Jones lifted his glass to his lips and drank, politely attentive. “You had said something about fomenting revolution.”

“Revolution here. Eventually,” Lesa said.

“If you’re busy fighting a civil war–”

“ Afterwe bring our support to a rebellion on Coalition‑controlled worlds. That means replacing the government, but we do that every three years anyway, and if we make Claude look bad enough, when we call for a vote of no confidence we’ll get it. The Coalition’s advances come in handy, actually. There’s nothing like an external enemy to unify political opponents.” She smiled. “You can even send home reports that you’re working to weaken Claude’s administration, and be telling the truth.”

Kusanagi‑Jones rubbed the side of his nose. “The other issue. Robert.”

Lesa nodded, biting her lip.

“He knows all this?”

“We’ll bring him in. Don’t worry. If he’d gone to Claude, I’d be in custody, and she wouldn’t be trying to discredit you.”

Kusanagi‑Jones snorted. “Unless she’s waiting to see who else we implicate. You suppose diplomatic immunity will keep Singapore’s people from shooting us as spies?”

“Depends,” Vincent said, “on how badly they want a war.”

Later, after a more in‑depth discussion of the details of alliance with Lesa, Vincent paced the bedroom while Angelo curled, catnapping, on the bed. Angelo was breathing in that low, gulping fashion that meant nightmares, but Vincent set his jaw and didn’t wake him. He needed the sleep too much, no matter how poor its quality.

And Vincent needed the time to think.

Axiomatically, there came a point in any secret action where the plan failed and the operative was left to improvise. And when that happened, the best option was a lotof options. He wasn’t about to close off any doors until he had to–with Lesa, or with Kyoto.

Or with Michelangelo.

Angelo’s second report on Kii had been more detailed, including not just the ultimatum, but some of Angelo’s conjectures as to what “Consent” might be. Enough to set Vincent’s fingers twitching. Angelo’s revelations about the city’s resident–Transcendent–Dragon were the most interesting development, especially when combined with the unforeseen complication of having taken refuge in Pretoria house.

While their temporary accommodation was restful, with the storm passed and the walls revealing a panoramic view of expanses of jungle canopy, seen from above, it was also inconveniently far from the gallery. And the interface room Michelangelo had discovered there.

And Angelo thought Vincent should talk to Kii.

Vincent was disinclined to argue. What an intoxicating idea: an alien–a realalien. A creature of mythic resonance.

Intoxicating, and terrifying. Vincent wasn’t remotely qualified to handle this. And there was the practical problem of how to get there without telling Lesa about the Dragon in her basement, since Angelo seemed to think she didn’t already know. He paced slowly, trying to make the space he had to walk in seem longer, and became aware that Angelo had awakened only when he spoke.

“Should ask to examine the crime scene in the morning.” He sat up as Vincent turned to him, leveling his breathing. He didn’t look any more rested.

“Dreams?” Vincent asked. Angelo dismissed the question with one of his sideways gestures, as if deflecting a blow, but Vincent leaned forward and gave him the eyebrow.

“ Skidbladnir,if you must know.” Angelo turned away, not bothering to hide the lie. “Can we be transferred back to our original rooms tonight? For convenience’ sake?”

“Once you’ve accepted Elder Singapore’s challenge.”

“Once Miss Pretoria has accepted it for me,” he replied, leaning back on his elbows. “How’s your back?”

“It hurts,” Vincent said. “But improving. I think the docs are getting some purchase on it.” He used their private channel to continue. “You don’t suppose your new friend is limited to appearing there,do you?”

“Pretty silly if he were.”

“So he probably knows what happened to the statue.”

Angelo was out of bed before Vincent realized he was standing. “He probably knows all sorts of things. The question is, if he’s ethical, will he sharethem?”

Volley and return. Sometimes surprising things came up that way. Vincent batted it back. “How do you suppose his ethics stack up to ours? Do you think they have anything in common?”

Angelo paused, scuffing one foot across the carpetplant. “He’ll avoid the unnecessary destruction of sentient organisms. Or, esthelich,his word. Get the feeling it’s not exactly what we’d call sentient.”

“Right. And he likes pets.”

The look Angelo gave Vincent could have fused his wardrobe. “Ironic, isn’t it?”

“Quite.”

“So what do we do?”

Vincent rocked on his heels, folding his arms. “We ask?”

“Here?”

“Why not? It’s not as if anyplace in this city is free of surveillance, and we have to assume Kii has some control of House, if he’s observing the citizens–”

“–denizens. Think he’s as concerned for the khir as he is for the Penthesileans.”

“Granted.” Vincent bit his lower lip and frowned at Angelo until Angelo licked his lips and looked down.

And then he dropped channel and said aloud, “House, Vincent and I would like to speak to Kii, please. Privately.”

For a moment nothing happened. Then the rippling leaves of the rain forest canopy fluttered faster, sliding together like chips of mica swirled in a flask, layering, interweaving, a teal‑colored stain creeping through the gathered mass until it smoothed, scaled, feathered, and blinked great yellow eyes at them. “This chamber is private,” the hologram said. “Greetings, Vincent Katherinessen. You speak to Kii.”

Angelo’s description hadn’t prepared Vincent for the reality of Kii. That serpentine shape emerging from camouflaging jungle triggered atavistic responses, an adrenaline spike for which his watch barely compensated. He took one unwilling step back anyway, shivering, and forced himself to pretend calm. “Kii,” he said, as soon as he could trust his voice. “I’m very pleased to meet you.”

And then he bowed, formally, as he would have on Old Earth, rather than taking a stranger’s hand. Kii seemed to bow as well, its head dropping on its long neck as it took advantage of apparent depth of field to slither a meter or two “closer.”

“You oppose your government’s agenda for this population?”

Vincent swallowed. Angelo stood at his shoulder, silently encouraging, and it was all Vincent could do not to glance at him for support. But he didn’t care to take his eyes off Kii. The Dragon’s direct, forward gaze was intent as any predator’s, and meeting it made Vincent very aware that he was small and–mostly–quite soft‑fleshed.

“We wish to assist you in protecting New Amazonia from Coalition control. We wish to preserve that population as well.”

“But not its Consent.”

“No,” Vincent answered. “Not its Consent. Its…Consent is not the will of the governed.”

Kii hissed, just the breathy rush of air from its jaw, without any vocal vibration. It wasn’t actually talking,Vincent realized. He was hearing sounds, but they didn’t match any vocalizations the Dragon made. “You are very strange bipeds,” it said. “The Consent is that Kii shall not aid you.”

It was not, Vincent told himself, unexpected. He closed his eyes for a moment, though it was an effort breaking Kii’s regard. “So you deliver your ultimatum, and leave us to it?”

“It is the Consent,” Kii said, unperturbed. “It is Consented that Kii may observe and speak with you, and continue Kii’s attempts to help your local population adapt. And protect them and the khir, as necessary.”

Vincent sank down on his haunches, tilting his head back, up at the looming Dragon. It was comforting to make himself smaller. “Kii, can you use your…wormhole technology to connect points in the local universe?”

“Spatial travel? No. Only parallel branes,” Kii said. “The wormholes must lie along a geodesic, and they must transect, or be perpendicular, orthogonalto the originating, no, the initiating brane. It is not the Consent to provide technology.”

“So you didn’t just plunk one down beside your sun for power,” Angelo said, resting one hand on Vincent’s shoulder, his knees a few inches from Vincent’s tender back. Kii’s nictitating membranes slid closed and open once more.

“We couldn’t give it to them anyway, even if Kii would provide it,” Vincent said, craning his neck to get a look at Michelangelo’s face. “Maybe a power feed. Not the generator technology. It’s not an option under any circumstances.”

Angelo scratched the side of his nose, staring down at Vincent as if it were an everyday occurrence for Kii’s holographic head to hover over both of them while they argued. “If they can’t use it for travel, or as a weapon within this universe, tell me why.”

“Gravity,” Vincent answered. He licked his lips and tilted his head back again, addressing Kii directly. “Just because you can’t make a wormhole open under your enemy’s feet doesn’t mean you can’t use this as a weapon. Kii, correct me if I’m wrong, but do your manipulations of branes cause tidal effects?”

“We amend for them,” it said. “But you are correct. There is gravitational pollution. Some we harvest as an additional energy source, or to create effects in the physical universe.”

“Such as tucking a nebula around your star to hide it from random passers‑by?”

The Dragon’s smile was an obvious mimicry of human expressions, on a face never meant to host them. Its ear fronds lifted and focused, the feathery whiskers that made its muzzle seem bearded sweeping forward, as if focusing its senses on Vincent. “Such as,” it said.

Vincent held his face expressionless as much by reflex as by intent. Michelangelo shifted, broke contact, and sat down on the carpetplant with a plop. “Can’t give the Coalition that. If they didn’t break something on purpose, they’d break it by accident.”

“Can they be educated?”

“Have you metmy species?” Michelangelo snapped.

Vincent burst out laughing and caught his arm. “Kii, can the Consent limit what it provides?”

“The Consent is not to provide.”

“If it did–does the Consent ever, uh, change its mind?”

“The Consent is sometimes altered by a change in circumstances,” Kii said. “But the current probabilities do not indicate it likely. The Consent is to defend.”

Vincent rolled to his knees and pressed himself to his feet, careful of his twinging knee. He thought better if he walked, despite the unsettling oscillation of Kii’s head as it followed him. Michelangelo scooted back against the bed, out of the way. “If we could present a convincing argument, do you think the Consent would authorize us to build receivers? Only? Or even provide them, as a solid‑state technology, for trade? That export would provide the Consent with leverage over the Coalition. They would have something to risk, in opposing you.”

Kii sunk lower, resting its chin on the interlaced knuckles of its wing‑joint digits, the extended pinkie fingers folded against its sides. “You wish a crippled technology?”

“Why not?”

“It could be arranged. The Consent will contemplate it.” Kii considered, and tilted its long head toward Michelangelo. “This, Kii is not forbidden to impart, Michelangelo Osiris Leary Kusanagi‑Jones. There is a weapon in your blood.”

Kusanagi‑Jones heard the words plainly, but they didn’t process at first. He was tired, overstimulated, still unsettled with the dream he’d lied to Vincent about. It hadn’t been Skidbladnirat all, but the old dream, the one of Assessment. But it hadn’t been his death he’d dreamed this time, or his mother’s.

It had been Vincent’s.

He looked down at his hands, as if expecting to see what Kii meant, and then his eyes flicked up again and he bounced to his feet. “Bioweapon.”

“Yes.”

Of course, Old Earth didn’t need to invade New Amazonia. They could do it the easy way. And the months in cryo to help time the latency right. “The Coalition didn’t–”

Kii reached forward, as if to sniff, or sweep its whiskers and labial pits across Kusanagi‑Jones. But its head was nothing more than a projection in the holographic wall, and Kusanagi‑Jones was treated to the bizarre perspective of the Dragon seemingly lunging for him, and never arriving. Kusanagi‑Jones locked his hands on the edge of the bed and held his ground, when he wanted to flinch and shield his eyes. It isn’t real.

“Since yesterday,” Kii said. “The infection is new.”

Kusanagi‑Jones turned toward Vincent, who stood framed against the evening light filtering through the doorway to the balcony. “Saide Austin,” he said. “Bitch.”

Vincent stepped forward, and Kusanagi‑Jones stepped away. Since last night. Which meant that Vincent had no more than casual exposure, and–“How long?”

“It is a tailored retrovirus,” Kii said. “It will affect only certain genetic strains of the human animal.”

“Mine,” Kusanagi‑Jones said.

“Yours. In females, it will not express to disease. Kii estimates the latency period to be on the order of part‑years.”

“The Penthesileans turned you into a bioweapon?” Vincent took another step forward, and this time Kusanagi‑Jones let him.

“Time bomb.” Kusanagi‑Jones bent over his watch, running diagnostics, search routines, low‑level scans, calm despite the twisting tightness in his chest. “Not even a blip. My body thinks it’s me. Supposed to carry it back to Earth and– pfft!” He waved his right hand in the air, still hunched over the green and blue lights glowing under the skin of his wrist.

“The New Amazonians think genetic tailoring is anathema.”

“Not anathema enough–”

Kii shifted, fanning and refolding its wings, a process that involved leaning back on its haunches to get them clear of the ground. “Kii has subroutines to contain the infection,” it said. “The Consent is indifferent with regard to Kii’s dealings with individuals. Kii may intervene in this thing.”

Vincent grabbed Kusanagi‑Jones’s arm and pulled him forward, front and center before the hologram. “You can cure him.”

“Kii can,” Kii said. The ragged‑edged patterns on its wing leather showed bold against blue sky as it beat them twice. Kusanagi‑Jones flinched from expected wind, but felt nothing.

“Wait.”

“No wait.” But Kusanagi‑Jones shook Vincent’s hand from his arm and dropped to their subchannel.

“You trust him? You can’t processthat thing, you know.”

“You don’t think there’s a virus? It makes Claude Singapore’s plan make a hell of a lot more sense, doesn’t it? Get you sent home, in disgrace, maybe brought before the Coalition Cabinet to testify, make all their separatist friends happy.” Vincent glanced sideways at Kii.

“First thing we do, let’s kill all the men.”

Kii, filling an apparent silence, said, “Your genotype proves resistant, Vincent Katherinessen.”

“Don’t know,” Kusanagi‑Jones said, over Kii. “If there is, it’s hiding in plain sight–You trust him.”

“It’s not human body language.”

“You trust him anyway.”

Slowly, Vincent nodded. He reached out gently and took Kusanagi‑Jones’s arm again, folding his fingers around the biceps and holding on like a child clinging to an adult’s finger.

“Bugger it,” Kusanagi‑Jones said out loud. “So do I.” He waved at Kii. “Do we know it’s fatal?”

“Kii estimates a 93 percent mortality rate.”

“Cure him,” Vincent said.

And again, Kusanagi‑Jones stepped away from his partner and said, “Wait.”

17

LESA DID NOT WANT TO TALK TO HER MOTHER. SHE MOST particularly had no desire at all to tell Elena the truth about Robert, and she was still working out her spin when the door to her office irised open again, admitting Katya. Her hair was bound back in a smooth, straight tail, and–an out‑of‑character note–her honor was strapped over garish festival trousers.

“I’m going out,” Katya announced, a conclusion Lesa had already drawn. “Do you want anything?”

“No. Thank you. Home for supper or out all night?”

Katya looked down. “It depends if I find a good party.”

The relationship between Lesa and her middle child had always resembled an arms race. Katya had been determined to become unreadable since she was a small child and she was often successful. But Lesa could almost always tell when she was hiding something, if not what she was hiding.

Lesa laid her stylus across the finished response to Claude she had been staring at, and folded her hands over it. Please let it be something innocent. A secret lover, a questionable hobby. Anything Katya thought Lesa should disapprove of.

Anything, but knowing where Robert was and concealing it from the rest of the household.

“All right,” Lesa said. “Try to stay out of fights.”

“Mom.”Katya paused before making good her escape. “Oh, and Grandma wants to see you. She’s up in the solar.”

“Wonderful.” Lesa levered herself from her chair, leaving the stylus laid across the desk but slipping the card into an envelope. “That’s what I was waiting for. Thank you, Katya.”

“No problem.” Katya grinned before slipping out the door.

Lesa followed, but turned right instead of left. She worried at her thumbnail with her teeth as she strode down the short, fluted corridor and climbed the stairwell past the second floor, where Vincent and Michelangelo were temporarily housed. Sweat trickled down her neck by the time she reached the third story and stopped in her own room.

It was full of evening light. Walter dozed in his basket, warmed by a filtered ray of sun, and for three or four ticks she contemplated activating the beacon in his collar and sending him after Katya. But that would hardly be subtle; it wasn’t as if he could be told to hidefrom her.

Lesa would have to track Katya herself, after she spoke to Elena. That would give Katya enough of a head start. In the meantime, Lesa combed her hair, changed her shirt, and went to talk to her mother.

Elena’s solar was at the top of Pretoria house, and Lesa took the lift. That climb was above and beyond the call of casual exercise in the service of keeping fit.

The room was pleasantly open, airy and fresh, with the windows on the sunset side dimmed by shades currently and the other directions presenting views of the city, sea, and jungle. Elena stood at the easternmost side, staring over the bay and its scatter of pleasure craft and one or two shipping vessels cutting white lines across glass blue.

“How much trouble are we in?” Elena asked before Lesa could announce her presence.

Lesa crossed the threshold, stepping from the smooth warmth of House’s imitation of terra‑cotta tile to cool, resilient carpetplant. “It’s less bad than it could be. Antonia Kyoto has injected herself into the situation.”

“What?” Elena’s voice shivered; through the careful modulation, Lesa read the blackness of her mood.

“She’s Parity. Robert was doubling for her.”

Elena laid her hands on the window ledge and tightened her fingers until the tendons on her wrists stood out. “Of course he was. I’ll have him flogged for that.”

“It gets worse.”

Elena turned away from the window. “By all means, draw out the suspense.”

“He didn’t run away to Antonia.”

“Then where, pray tell?”

Lesa held her hands up, open and empty.

She heard Elena take two slow breaths before she spoke again. “Oh,” she said. “I see.”

“There’s good news,” Lesa added hastily. “I’ve talked with Katherinessen, and it seems I was wrong about Kusanagi‑Jones. He’s sympathetic, and brings Free Earth assets to the table.”

The latest indrawn breath hissed out again in a sigh. Elena closed her eyes briefly and nodded. “That is good news. And the deal with Katherine Lexasdaughter?”

“Proceeds. She stands ready to present a united front with us. Vincent–Miss Katherinessen–came very well prepared. Kusanagi‑Jones less so, in that he’ll have to carry word of our plans to his contacts on Old Earth personally.”

“Of course, out of twenty named worlds, the defiance of three won’t make much difference in terms of military might.”

“No,” Lesa said. “But House will protect us. And it will mean something in terms of leadership. We just need to show that the Coalition canbe opposed. I’ve provided a full report on the Coalition agents, anyway.” She stretched her back until it cracked, and pitched her voice higher. “House, would you send the report to Elena’s desk, please?”

The walls dimmed slightly in answer, and Elena nodded thanks. “There’s something else.”

“News travels fast.”

Elena’s smile only touched one corner of her mouth. “Agnes said Kusanagi‑Jones received a challenge card.”

“From Claude, yes.”

“What’s he going to do about it?”

It was Lesa’s turn for a collected smile. “I’m going to fight for him.”

“Wait?”Vincent snapped, but Angelo met his gaze with that infuriating impassive frown. Vincent’s fingers tightened against his palm, as if there were any way in the world he could make Angelo do anything he hadn’t already meant to do.

“Can you think of a better plan?” And oh, his voice was so damned reasonable when he said it. “Cheaper than a war.”

“It’s not what I would call ethical,” Vincent said. He glanced up at Kii for support, but the Dragon only watched them, feathered brows beetled over incurious eyes. “You’ve no way to control it, and it will cost a lot of innocent lives.”

“It will,” Michelangelo said, folding his arms, his face relaxing into furrows of worry and grief. “And at least one not so innocent one.”

He meant himself. And he was letting Vincent seehim, the whole story, nothing concealed. The intimacy rocked Vincent in sympathetic waves of Michelangelo’s fear and desperation. He was scared sick. It was in the creases beside his eyes, the crossed arms, the slight lean back on his heels. Scared, and he thought it was worth doing anyway.

Killing off nearly half the population of Old Earth would sure as hell limit the threat of the OECC as a conquering power, Vincent would give Michelangelo that. He still didn’t think it was the world’s greatest solution to the problem.

“You’re not doing this,” Vincent said. “That’s an order.”

“The alternative is letting Old Earth drag the Coalition worlds into a fight that Kii and the Consent would end when it got to New Amazonia. Probably get twice as many killed on both sides. Nuclear option, Vincent. It will save lives.”

Kii’s feathered tufts ruffled and smoothed. “We would not be pleased to do so.”

“No,” Vincent said. “I don’t imagine you would. Kii, I have another option. Would the Consent, uh, consent to teach my people to create Transcendent matrices such as yours?”

“Your species may not be suited.”

“What do you mean?”

“My species chooses to copy our psyches into an information state, and to permit our physical selves to grow old and fail.”

“Of course,” Vincent said. It wasn’t as if one could actually uploadone’s personality, stripping the man out of the brain and loading it into a computer like a Raptured soul ascending bodily to heaven. One made a copy. And that left the problem of what to do with the originals.

“We accepted that to do so, our physicalities must die without progeny. The Consent was given, and so it was…wrought. No, so it abided.” Kii angled its nose down at them. “Kii thinks biped psychology is unamenable to such constraints.”

“Bugger,” Angelo said into the silence. “Shove it down their throats if we have to–”

“No,” Vincent said, rubbing his hands through his braids so the nap of his hair scratched his palms. “We’d have to sterilize the lot. An entire planetary population for whom procreation is the most cherished ideal? It wouldn’t change anything, except we’d have Transcendent copies of them in a quantum computer leading productive virtual lives. The plague’s a better idea. Which is not to say it’s not a lousy idea.”

He glared at Michelangelo, and Michelangelo unfolded his arms, a gesture of acceptance but not surrender. “We’ll wait,” he said. “For now. Try to come up with something better.”

“You’re content to walk around breeding retrovirus for the next two weeks?”

Angelo echoed Vincent’s gesture, palms across his scalp, but his version added a yawn. “Sounds a regular vacation, doesn’t it?”

On the way out, Lesa stopped in her room, discovered that Walter had apparently gone to the courtyard to stretch his legs, and got a leash before heading down to collect him. Far from gamboling with the children, the khir was sprawled in a sunbeam, sides rising and falling with steady regularity.

Awakened from his nap, he stretched lazily front and back and trotted around her twice on her way to the door, as if to prove that lesser khir might need to be leashed, but he certainly didn’t. All his blandishments were in vain. She clicked the leash to his collar as they stepped out the front door, and then crouched to tap the veranda with her forefinger and say, “Find Katya.”

Walter whisked his muzzle across the deck and picked his way down the stairs, pausing at the bottom to sniff again before angling left, toward the bigger thoroughfare, threading between merrymakers at a rate that had Lesa hustling to keep up. She trotted, too, keeping the leash slack, though Walter occasionally turned to glare. “I’m running as fast as I can!”

He didn’t seem to believe her, but he was too well trained to lunge at the lead, even when irritated by streets clotted by buskers and food vendors. It had been Lesa’s idea to train the household khir as messengers, when she was Katya’s age, an idea that had turned out well. So well that other households had copied the trick once they found out how adept the khir were at memorizing routes.

The pace he set was better than a jog. Her honor jarred on her thigh with every footstep; her hair disarrayed and stuck to her forehead with sweat. She clucked to Walter, slowing him as they threaded between people so they wouldn’t accidentally trample other pedestrians and spark a duel, or overrun Katya and have rather a lot of explaining to do.

That Katya had gone on foot heightened Lesa’s suspicions. If she’d called a car–either public transport or Pretoria house’s communal one–her destination would have become a matter of record. Walking for exercise was one thing, but it was early for parties, even in Carnival, and if Katya weregoing to parties, she wouldn’t want to arrive sweat‑saturated and stinking.

Lesa had always encouraged Robert to know her children, to develop relationships with them, far beyond the customary. He had, and both Robert and the children had seemed to enjoy it.

And now Katya was making Lesa pay for it.

It had seemed like a good idea at the time.

After their dead‑end conversation with Kii, Vincent had happened to be watching when Lesa appeared in the courtyard, whistled for her pet, and snapped a leash onto his collar. “Angelo,” he’d said, without turning, “follow her.”

Which was how Kusanagi‑Jones came to be slipping through the steadily increasing press of cheering, staggering, singing men and women behind Lesa and her animal like the sting on an adder’s tail, following the rest of what he took to be a long and somewhat complicated snake. Vincent remained at Pretoria house, nursing his sunburn and wrenched knee and covering Kusanagi‑Jones’s tracks, but the drop from their balcony was only four meters and Kusanagi‑Jones could have done it without tools, stark naked and on a sprained ankle.

Fully equipped, he could almost take it as an insult how easy escape had been.

Robert’s decampment was more interesting, and Kusanagi‑Jones was still trying to comprehend it. Based on his imperfect understanding of the layout of Pretoria house, the men’s quarters were isolated well up the tower and guarded. It was a descent that could not be made inobviously on ropes, especially in the middle of a festival, and if the guard had not been overpowered, the obvious solution was that somebody inside the house had assisted Robert in getting out.