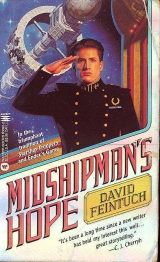

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

But Mr. Malstrom obviously wanted to talk about it, and once he had been my friend Harv.

“No.” His face hardened. “Court-martial.” Seeing my surprise he added, “Those scum knew what they were doing.

They broke a dozen regs just getting the stuff aboard ship.

Then they caused a major riot among the crew. What if they’d gone berserk on duty stations, instead of in their bunks? In the engine room, or the airlock?”

He was right, up to a point. The sailors’ stupidity might have wrecked our ship. But it hadn’t; we’d dealt with them in crew quarters. Captain’s Mast, or nonjudicial punishment, would mete out demotion, pay decreases, or extra duties.

A court-martial was far more serious. While Hiberniawas interstellar, far from home, the men could be punished with the brig, summary dismissal, or even execution.

Instead of putting the incident behind us, court-martial would formalize and enlarge it. Worse, the matter would drag on unhealed while the court-martial was convened, poisoning relations between the enlisted men and officers.

“Yes, sir. I understand.” It wasn’t my place to tell him my reservations.

“I’m appointing Pilot Haynes as hearing officer. Alexi will be their advocate.” “Alexi?” I was so astonished I forgot my discipline.

“Sir,” I quickly added, to correct my breach.

“Who else? It has to be an officer. Chief McAndrews found the stuff; he’ll be a witness like you and Vax. Sandy has to present the evidence against them. There’s no one else left.”

“Doc Uburu?”

“Doc treated the injured and conducted the interrogations.” The Captain was right; he had no more officers to call on.

“Aye aye, sir.” I began figuring how to relieve Alexi from his watches, so he’d have more time to study the regs.

The court convened three days later, in the vacant lieutenants’ common room where the Board of Inquiry had met. In all, fifteen men were charged. Three were accused of organizing the still, taking part in the riot, and assaulting a superior officer. They were in the worst trouble of all. Five more were charged with use of contraband intoxicants, four of those with rioting as well. Seven others were charged with taking part in the melee.

It wasn’t as complicated as it sounded. Petty Officer Terrill knew which two sailors had worked him over: one of the men who was accused of using the goof juice, and one of the three distributors. Several of those charged with rioting pled guilty to all charges, throwing themselves on the Captain’s mercy.

Two of the men accused of using the goofjuice also pled guilty.

The Captain was not lenient; he sentenced four of the men to six months in the brig and busted three others right down to apprentice seaman. Then the trials of the remaining eight got under way.

The three men charged with supplying the goofjuice were tried first. Pilot Haynes, sitting at the raised desk, listened impassively while Alexi Tamarov haltingly argued on behalf of his clients. It was no kangaroo court; when the Pilot felt the middy was not bringing out a defensive point, he put aside his preferred reticence and questioned the witness himself.

The three hapless sailors whispered with Alexi from time to time, interrupting his questioning of Chief Me Andrews.

“Was the vial under a particular bunk when you found it, sir?”

“Not completely,” said the Chief, unruffled. “The box was on the deck, half pushed under a bunk.”

“So you don’t know for sure that it was in Mr. Tuak’s possession, sir?” Alexi was doing his best on a hopeless case.

Tuak had already confessed under P and D. As was his right, he recanted his confession, but of course it would be entered against him. Alexi was casting about for other evidence to discredit it.

“I don’t know, Mr. Tamarov.” The Chief was undisturbed; other witnesses had identified the box as belonging to Tuak.

“Sir, did you see anything that contradicts Mr. Tuak’s having been framed by another sailor?”

“Yes.” Alexi looked surprised and worried, but had no choice but to let the Chief answer. “When he recovered from the stun charge, Mr. Tuak tried to claw Mr. Vishinsky’s face.”

“Could that have been from anger at having been stunned unjustly?”

“It could have,” said the Chief, his tone making clear he didn’t believe it.

The trial droned on. I was called as a witness, but had little to offer except a description of Mr. Vishinsky quelling the riot. Neither Sandy nor Alexi seemed much interested in my testimony.

The trial, I reflected, was mostly ritual. It could help disclose truth, but that has rarely been necessary since P and D testing became the norm. Yet we still observed the old forms in civilian as well as military courts: defense attorneys, prosecutors, witnesses. In nearly all cases we already knew the outcome.

While the trial was in recess I wandered into the passengers’ lounge, looking for a conversation to distract me.

Perhaps Mrs. Donhauser and Mr. Ibn Saud were at it again.

1 found two older passengers I barely knew, reading holovids. One of the Treadwell twins, the girl, was writing a game program; she tested it from time to time on the passengers’ screen. Derek Carr, lean, tall, aristocratic, studied the holo of the galaxy on the bulkhead, hands clasped behind his back.

I stood near him, lowering my voice. “My condolences, Mr. Carr. I never had a chance to speak to you after your father’s death.”

“Thank you,” the boy said distantly. His eyes remained on the holo. It was a dismissal.

“If there’s anything I can do, please let me know.” I moved away.

“Midshipman.” He didn’t even know my name, after sitting at table with me a month. I waited. “There’s something you can do. Talk with me.” He hesitated. “I need to speak to someone. It might as well be you.”

Graciously stated. I made allowances for his bereavement.

“All right. Where?”

“Let’s walk.” We strolled aimlessly along the circumference corridor, passing the dining hall, the ladders, the Level 2 passenger staterooms.

He said, “My father and I own property on Hope Nation.

A lot of it. That’s why we were going home.”

“Then you’re provided for.” I spoke just to keep the conversation going.

“Oh, yes.” His tone was bitter. “Trusts and guardianships; my father had it all worked out. He showed me his will. The banks and the plantation managers will run the estate for years. I won’t get anything until I’m twenty-two.

Six years! I mean, I won’t starve. But it’s not like... “

After a while I prompted, “Like what, Mr. Carr?”

He looked into the distance, beyond the bulkhead. “He’d been training me to run the plantations. He taught me bookkeeping, the crop cycles. We made decisions together. I thought... “ His eyes misted. “My father and I... We had money, we had a good life. I thought it would always be that way.”

Thrusting his hands in his pockets he turned to me, his eyes bleak. “And now it’s all gone. I’ll be treated like a joeyboy again. Nobody will listen. No one will care. It’ll be years before I can do anything about it.”

I said nothing, taking it in. “Do you have a mother?”

“No, I’m a monogenetic clone. Just my father.” Not an uncommon arrangement of late, but I wondered how it would feel. Back home in Cardiff we were more conservative; I carried my host mother’s genes as well as Father’s, though I’d never met her. After a moment Derek added, “I thought you might understand, being my own age and all. And having responsibilities.”

“Yes, I understand. Tell me something, Mr. Carr.”

“What?”

I probably shouldn’t have said it, but I was overtired and my nerves were on edge. “Do you miss your father?” He stiffened at my tone. I added, “You haven’t mentioned how you feel about him. Just the advantages he gave you.”

He was furious. “I miss him. More than a person like you will ever know. Forget we spoke.” He stalked back down the corridor.

I strode quickly to catch up. “How do you expect me to know, when you keep it hidden?”

He took several more steps before slowing. Finally he stopped, hand against the bulkhead. “I don’t wear my feelings for everyone to see,” he said coldly. “It’s uncouth.”

I felt I owed him something for jabbing at him. “The day I went to Academy at Dover, I was thirteen. My father brought me to town. I had my belongings in a duffel I carried at my side. Father walked me to the compound gates, his hands in his pockets, saying nothing. When we reached the gate I stopped to say good-bye. He turned my shoulders around and pushed me toward the entrance. I started walking.

When I looked again he was striding away without looking back.” I paused. “I dream about it frequently. The psych .

says I’ll probably outgrow it.” I took a couple of breaths to restore calm. “It’s not the same, Mr. Carr, but I know what loneliness is.”

After a pause Derek said, “I’m sorry I snapped at you, Midshipman.”

“It’s Seafort. Nick Seafort.”

“I apologize, Midshipman Seafort. My father always said we were extraordinary, and I believed it. In a way we are.

It’s hard to remember other people have feelings too.”

We wandered back to the lounge, saying nothing. At the hatch we stopped, and after an awkward moment we shook hands.

8

According to ritual Mr. Tuak stood in front of the presiding officer’s desk with his advocate, Alexi. The two stood at attention while Pilot Haynes declared his verdict.

“Mr. Tuak, the court finds you guilty of the offense of possessing aboard a Naval vessel a contraband substance, to wit, a magnesium starch colloquially known as goofjuice.

The court nominally sentences you to two years imprisonment for this offense.” The court always imposed the maximum sentence provided for in the regs, a nominal sentence subject to review and reduction by the Captain.

“Mr. Tuak, the court finds you guilty of the offense of rioting aboard a vessel under weigh. The court nominally sentences you to six months imprisonment and loss of all rank and benefits.” Pilot Haynes stopped for breath. It was the longest speech I had ever heard him make.

“The court also finds you guilty of striking a superior officer, to wit, Mr. Vishinsky, and likewise Mr. Terrill, in an attempt to prevent the performance of their duty. The court sentences you–nominally sentences you–to be hanged by the neck until dead, and remands you to the master-at-arms for execution of the sentence.”

Even though the sentence was known and expected, Alexi’s shoulders fell and his head bowed. Tuak stood unmoving, as if he hadn’t heard.

After, in the wardroom, I tried to comfort Alexi. He had been crying and paid no attention to my consolation. Vax watched as I fumbled at Alexi’s arm, muttering inane words.

After a time the burly midshipman tapped me on the shoulder and motioned me aside. He sat on the bed next to Alexi and put his big hand on the back of the younger middy’s neck, squeezing the muscle gently.

“Let go; I’m all right.” Alexi tried to pull away Vax’s hand.

“Not until you listen.” His hand stayed where it was. “My uncle is a lawyer. A criminal lawyer back in Sri Lanka.”

“So?”

“He once told me the hardest part of his job. He liked his clients, some of them.” Vax waited, but Alexi made no comment.

“When he couldn’t get his clients freed, the hardest thing for him to remember was that it was their own fault they were in trouble, not his. They were in jail not because he had failed them, but because they had fouled up in the first place.”

“There must have been a way to get him out of it.” Alexi’s voice was muffled, but at least he was listening.

“Not in this Navy.” Vax spoke with certainty. He picked up the younger middy and turned him over onto his back.

Again I wished for Vax’s strength. “Read the regs, Alexi.

They’re designed to protect authority, not to encourage flouting it.”

“But executing him–”

“That’s for the Captain to decide. Anyway, he’s a drug dealer. I have no sympathy for him. Why should you?”

I sat down on my bunk. I wasn’t needed anymore.

“But they might hang him!” Alexi propped himself up on an elbow. “Look, I know you want me to feel better. But tell me Lieutenant Dagalow couldn’t have done something to save him!”

“Lieutenant Dagalow couldn’t have done anything to save him,” Vax said evenly. “A ship under weigh is under the strictest military rules. It has to be, to preserve order and lives. The rules are clear. What happened down in berth three was nearly a mutiny. You don’t think mutineers should get off, do you?”

“Of course not!” Alexi said indignantly. It was unthinkable to us all.

“Tuak struck an officer in the performance of his duty.

That’s a form of mutiny. You have a hell of a nerve sympathizing with him, Tamarov!”

Alexi was smart enough to make the distinction. “I don’t sympathize with what he did, just the penalties. Sometimes we’ve screwed up too, you know. You mutinied against Mr.

Seafort, didn’t you?”

“Yes, and he let me off easy. Mr. Seafort should have taken my head off. I realize that, now.” Oh. Nice to know.

“Then we’re just luckier than Tuak,” said Alexi bitterly.

“No,” I intervened. “Mouthing off in the wardroom isn’t comparable to dealing drugs to the crew or hitting the CPO, and you know it.”

After a moment Alexi sighed. “I know,” he said. He sat up. “You joes realize I have to go through it again? With the other trials?”

We commiserated. The crisis was over.

The other trials began the next day. When they were done, two other unfortunate sailors were under sentence of execution for striking their officers. A variety of lesser penalties had been handed out to the remaining participants.

The Pilot formally presented his verdicts to Captain Malstrom. The Captain had thirty days to act; unless he commuted the sentences, they’d be automatically carried out by the master-at-arms.

During the next few days the officers watched for signs of tension among the crew. There was some bitterness, but on the whole the hands settled down. Our crew knew the ship needed authority at its helm, just as the rest of us did. If Captain Malstrom was troubled by the decision he had to

make, he didn’t show it. He relaxed visibly when it was clear the unrest was over. He laughed easily, joked with the younger passengers, and arranged a place for me several evenings at the Captain’s table, though it was not customary to favor an officer.

Once he even invited me to play chess. He knew I would be uncomfortable in the Captain’s quarters; they were so unapproachable I’d never been allowed to see them. We went instead to the deserted lieutenants’ common room.

We set up the board for the first time in many weeks. I didn’t play well, not by choice, but from nervousness. Playing the Captain was nothing like playing a second lieutenant. He seemed to sense my mood and chatted with me, trying to put me at my ease.

“Have you reached a decision yet, sir, on the rioters?” It was presumptuous of me, but Captain Malstrom seemed pleased by my attempt at intimacy. Perhaps he needed it.

His face darkened. “I don’t see how I can let them off and keep a disciplined ship.” He sighed. “I’m trying to justify commuting the death sentences; the thought of killing those poor men sickens me. But in good conscience, I don’t know how I can.”

“You still have time to decide.”

“Yes, twenty-five days. We’ll see.” He turned the conversation to Hope Nation. He asked if I still intended to buy him a drink. Yes, I said, knowing it was unlikely. A Captain on shore leave doesn’t carouse with middies. For one thing, he’s too busy.

After that day, something was wrong. I didn’t know what, but the Captain didn’t offer a smile when we met in the ship’s dining hall. He looked preoccupied and grim. I shared a four-hour watch with him and the Pilot. He hardly spoke. I assumed his decision about the death sentences was affecting his mood.

Two days later we Defused for a scheduled navigation check. The greater the distance in Fusion, the more our navigation errors would compound. It was customary on a long cruise such as ours to Defuse two or three times, replotting the coordinates each time.

We came out of Fusion deep in lonely interstellar space.

Darla and the Pilot both plotted our course. Their figures agreed with those of Vax, who as midshipman of the watch also ran a check. But instead of Fusing directly, the Captain laid over another night, drifting in space.

At dinner that night I sat two tables from the Captain. He seemed determined to be cheerful. I could see him teasing Yorinda Vincente, who laughed uncertainly, as if unsure of the right response. I looked for Amanda and found her across the hall at Table Seven with Dr. Uburu. I willed her to catch my eye. Eventually she did, smiled gently, turned away.

A forkful of beef halfway to my mouth, I watched the Captain reach for his water glass. He paused, a puzzled look on his face. He gestured and said something to the steward, who hurried to Table Seven. A moment later Dr. Uburu was kneeling by the Captain’s chair. Captain Malstrom was hunched over the table.

Two sailors serving the mess helped the Captain to his feet, supporting him from either side, guiding his unsteady steps toward the corridor. Dr. Uburu followed. I watched, agape.

There was no one senior to stop me. I excused myself and boldly left the dining hall for the corridor to the ladder. I ran up the steps two at a time to officers’ country. No one was in the infirmary except the med tech on watch. I hurried forward to the Captain’s cabin. Of course his hatch was shut.

It was unheard of to knock, so I waited.

After some minutes Dr. Uburu stepped out and shut the hatch.”What are you doing here?” Her tone was a challenge.

I wasn’t reassured by the look on her dark, wide-boned, face. “Is he all right, ma’am?”

She ignored my breach of discipline. “I can’t discuss the Captain’s personal affairs.” She started toward the infirmary.

I hurried to keep up. “Is there anything I can–I mean–”

I didn’t know what I meant.

Dr. Uburu was brusque. “Go back to the dining hall.

That’s an order.”

Phrased like that, she left me no choice at all. She was an officer, rank equal to a lieutenant, and I was a midshipman.

“Aye aye, ma’am.” I turned and left.

All next day the Captain was off watch. I asked the Pilot when we would Fuse; he shrugged and left it at that, and I knew I wouldn’t get any information from him. When my watch ended at last I went back to the wardroom. None of the other middies had heard anything reliable through the ship’s grapevine.

I was thinking about hunting for Amanda; I needed her comforting acceptance. But there came a knock on the wardroom hatch; the med tech was outside, ill at ease. “Mr.

Seafort, sir, you’re wanted in the infirmary.”

“Why the infirmary?” If anything, I was hoping for a summons from the Captain’s cabin.

“It’s the Captain, sir. He’s been moved there.” Vax and I exchanged a glance. I donned my jacket and hurried after the tech. Dr. Uburu indicated a cubicle; I went in alone.

Captain Malstrom lay on his side under a limp white sheet, his head propped on a pillow. The halogen lights hurt my eyes. He offered a weak smile as I entered and came to attention. “As you were.”

“How are you, sir?”

For answer he threw off the sheet. He wore only his undershorts. His side and back were a mass of blue-gray lumps.

I closed my eyes for a moment, trying to will them away.

“How long have you known, I mean, have they been–”

“Four days. They came up just a few days ago.” He made an effort to smile again.

“Is it... “

“It’s T.”

“Oh, Harv.” Tears were running down my face. “Oh, God, I’m so sorry.”

“Thank you.”

“Can she–are they doing anything, sir? Radiation, anticars?”

“There’s more, Nicky. She found it in my liver, my lungs, my stomach. I haven’t been able to see too well today, either.

She thinks it might be in my brain too.”

I didn’t care what they did to me. I reached out and took his hand. If anyone had seen, I could have been summarily shot.

He squeezed my fingers. “It’s all right, Nicky. I’m not afraid. I’m a good Christian.”

“But I’Mafraid, sir.” The situation began to sink in on me. “That’s why you didn’t Fuse.”

“Yes. I think... I’m not sure... whether to go back.”

He lay back, closing his eyes. He breathed slowly, hoarding his strength. We stayed as we were for several minutes. I began to realize what had to be done.

“Captain,” I said slowly, clearly. “You have to give Vax his commission. Right now.”

He came awake. “I hate to do it, Nicky. He can be such a bully. If he’s in charge and there’s no one to stop him... “

“He’s changed, sir. He’ll do all right.”

“I don’t know... “ His eyes closed.

“Captain Malstrom, for the love of Lord God, for the sake of this ship, commission Vax while you still can!”

He opened his eyes again. “You think I ought to?”

“It’s absolutely necessary.” What might happen otherwise was too horrible to contemplate.

“I suppose you’re right.” He was growing drowsy. “I’ll sign it into the Log. First thing in the morning.”

“I could get the Log now, sir.”

“No, I want to think about it overnight. Bring him in tomorrow morning, I’ll do it then.”

“Aye aye, sir.” He was sleeping by the time I reached the hatch.

Dr. Uburu faced me in the anteroom. “He ordered me to announce his illness to the ship,” she said. “Rumors are everywhere.”

“I know,” I said. I’d heard some of them.

She smiled warmly. It lighted her face and I was grateful.

“I’ll stay up with him tonight.”

“Thank you, ma’am.” I took her nod for a dismissal and left.

In the wardroom the other midshipmen questioned me silently. I had nothing to say to them; there was no way I could tell Vax he was going to make lieutenant, before Captain Malstrom had made up his mind. When the Doctor’s solemn announcement came over the speaker we all listened in silence. Afterward I slapped off the light. None of us spoke.

First thing in the morning I arranged for Sandy to take Vax’s watch. A quick breakfast in the officers’ mess, then I told Vax the Captain wanted to see us in the infirmary.

Dr. Uburu had been dozing at the table in the outer compartment; she woke when we came in. She said the Chief Engineer had already brought the Log chip from the bridge, on Captain Malstrom’s instructions. “He’s awake and wants to see you. He’s not doing too well.” Her tone was glum.

We entered the sickroom, snapping to attention. The Captain was dozing in his bunk. He heard the hatch close, and opened his eyes. “Vax, Nicky, hi,” he said vaguely. The ship’s Log was in the holovid on a small bunkside table, within his reach.

“Good morning, sir,” I said. He didn’t answer. “Captain, we’re here to do what you said last night.”

“I was having dinner,” he said suddenly, loudly.

“When you were taken ill, two nights ago, sir.” I tried to think how to direct him. Vax watched, puzzled. “Captain, last night we talked about Mr. Holser. Do you remember?”

“Yes.” Captain Malstrom smiled at me. “Vax, the bully.” An icicle crept up my spine. I wanted to move to him, but we were still at attention; he hadn’t released us.

I was so desperate I prompted him. “Sir, we talked about Vax’s commission. Don’t you remember?”

He came fully awake. “Nicky.” He studied me. “We talked. I said I would... make him looey. Of course!” I was weak with relief. He turned to Vax. “Mr. Holser, wait outside while we talk.”

“Aye aye, sir.” Vax spun smartly and left the room.

I took it as permission to move. I took the Log and dialed the current page. “Sir, let me help you. I can write; all you have to do is sign.”

Captain Malstrom began to weep. “I’m sorry, Nicky. I guess I have to give it to him. He’s the qualified one. You aren’t. I don’t have a–it’s the only way!”

“I know, sir. I want you to. Here, I’ll write it.” I took the.

laserpencil. “I, Captain Harvey Malstrom, do commission and appoint Midshipman Vax Stanley Holser lieutenant in the Naval Service of the Government of the United Nations, by the Grace of God.” I knew the words by heart, as did every midshipman.

I handed him the laserpencil. He stared at it, as if it were wild. “Nicky, I don’t feel well.” His face was white.

“Please, sir, just sign, and I’ll get Dr. Uburu. Please.”

He began to tremble. “I... Nick, I’ve–NICKY!” His head snapped back, his jaw clenched shut. His whole body shivered.

“Dr. Uburu!”

The Doctor came running at my yell. One look and she grabbed for a hypo, filled it from a medicine bottle in the cabinet nearby. “Move, boy!” She shoved me aside and bared his arm. As the hypo plunged, his rigid muscles slowly relaxed. His hand opened.”Give me the Log,” he whispered.

But his hand wouldn’t hold the pencil.

I said, “Captain Malstrom, commission him orally! Dr.

Uburu is witness!” The way it came out, it sounded like an order.

He muttered something. I couldn’t tell what it was. Then he drifted toward sleep. “This afternoon,” he said clearly, surprising me. “After I rest.” I waited, but his breath came in short rasping sounds. His face was flushed.

I took hold of the Doctor’s arm. I had touched the Captain, now it might as well be Dr. Uburu; I had lost all sense of propriety. I tugged her toward the corner. “Do you realize,”

I whispered, “what will happen if he doesn’t commission Vax?”

“Yes,” she said coldly, pulling my hand from her arm.

“He’s got to sign the Log! Will he be able to, this afternoon?”

“Perhaps. I have no way to know.”

“I heard him orally commission Vax. You did too.” I stared her straight in the eye, hoping she would realize what had to be done.

“I heard no such thing,” she said bluntly. “And you are a gentleman by act of the General Assembly. A gentleman does not lie!”

I blushed all the way up to my ears. “Doctor, he has GOT to sign that Log.”

“Then let’s hope he wakes up in condition to do it.” She added, “I agree with you. It’s necessary for the ship’s safety that he sign Vax’s commission.”

“But you won’t... “

“No, I won’t. And you won’t suggest it again. That is a direct order which you disobey at your peril! Acknowledge it.” She had steel in her. I hadn’t known.

“Aye aye, ma’am. I will not suggest again that Captain orally commissioned Vax. I accept your statement that he did not. Is there anything else, ma’am?”

“Yes, Nick. Duty is sometimes unclear. Right now your duty is to obey the regulations you swore to uphold. All of them. I trust that by the Grace of God the Captain will do what he must. You would do better to pray than to scheme, young man.”

“Yes, ma’am.” She was right.

Vax was waiting outside the sickroom. “What was all that about?” he asked.

We walked back along the corridor toward the wardroom.

Now he had a right to know. “I asked the Captain to commission you lieutenant. He said he would do it this morning. I wrote it out in the Log for him.”

“And?”

“He hasn’t signed it. He’s disoriented. I asked Dr. Uburu to agree that he had commissioned you orally, but she said he hadn’t. In truth, he had not.”

Vax took my arm. There was a lot of touching going on in Hibernia.“Why did you want him to?”

“Vax, what the hell happens when the Captain dies? Do you expect me to try to run the ship?”

I don’t think it had occurred to him until that moment. It had only occurred to me two days ago. “Oh, my God.”

“And mine.” We locked eyes. “We’ll come back in a couple of hours. He’ll sign it. He has to.” We walked the rest of the way in uneasy silence.

After lunch we returned to the infirmary. At my request Chief McAndrews also came. The Doctor, the Chief, Vax, and I waited in the sickroom for the Captain to awaken. He slept fitfully, tossing and turning. The silence in the brightly lit room grew unbearable.

Hours passed. “Is there anything you can give him?” I asked Dr. Uburu. “Some sort of stimulant?”

“Yes. If I want to kill him,” she growled. “His systems are closing down. He can’t take much.”

“He’s got to wake up long enough to sign the Log, or at least tell us orally!”

She shook her head, but after a while she loaded a syringe and gave Captain Malstrom an injection. Chief McAndrews sat near the bed; the Doctor was at a table close by. Vax stood stolidly against the bulkhead; I paced with increasing nervousness.

“Nicky.” The Captain’s eyes were open and riveted on me.”Yes, sir.” I hurried over to the bed. I picked up the holovid with the Log.

The Captain swallowed with difficulty. As I came closer he squinted to keep me in focus. “Nicky... you’re my son,” he said weakly.

“What?” My voice squeaked. I couldn’t have heard right.

I leaned close.

He raised a hand and touched my cheek. His breathing was ragged. “You’ve been... a son to me. I never had another.” “Oh, God!” It was too much for me; I wept. He touched me again; his hand moved uncertainly in front of my face before it found me. “I’m dying,” he said, with wonder.

Hating myself, I said urgently, “Sir, do your duty! Tell Chief McAndrews and Dr. Uburu that Vax is a lieutenant.

Tell them.”

“My son,” he said, dropping his hand. He stopped breathing. I turned frantically to the Doctor but the Captain’s breath caught again in a ragged gasp. He stared at me, his face an unhealthy blue. Understanding slowly left his eyes and they closed.

Dr. Uburu started intravenous liquids. While we waited helplessly, they dripped into his arm in the age-old manner.

The Captain lay unconscious, his mouth ajar.

“Do something. With all your machinery, help him!” My words were a demand.

“I can’t!” she spat. “I can pump his heart for him; I can even replace it. I can oxygenate his blood just as his lungs do. I can purify his blood with dialysis. I can even replicate his liver. We’re talented, aren’t we? But I can’t do all those things at once. He’s dying! The poor man’s insides are rotten; he’s like an overripe melon about to split open. The melanoma’s everywhere.”

She stopped for breath, her fury nailing me to the bulkhead.

“He’s got it in his stomach, his liver, his lungs, his colon.

His sight is going from an optic tumor. It’s as bad as T can get. Sometimes–only once in a while, thank God–it grows so fast you can see it. Do something? DO SOMETHING?I can stay with him to wish him into Yahweh’s hands. That’s what 1 can do!” Her cheeks were wet.

“And I can let him go in peace and privacy.” Chief McAndrews got heavily to his feet. “Nick, stay with him. If he rallies he’ll sign it. Or he’ll tell Dr. Uburu as witness. There’s no use my staying.” He left.