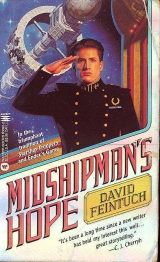

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

David Feintuch – Seafort1-Midshipman’s Hope

v1.0 Original PDF 12-Mar-2002

v1.1 Converted from PDF to HTML 12-Mar-2002. Made sure layout is correct (Checked chapter breaks etc. against the original PDF). No proofreading done.

PART I

October 12, in the year of our Lord 2194

1

“Stand to!” I roared, but I was too late; even as Alexi and Sandy snapped to attention, Hibernianstwo senior lieutenants strolled around the corridor bend.

We froze in stunned tableau: I, the senior midshipman, red with rage; a portly passenger, Mrs. Donhauser, jaw agape at the blob of shaving cream on her tunic; my two middies stiffened against the bulkhead, eyes locked front, towels and canisters still clutched in their hands; Lieutenants Cousins and Dagalow, dumbfounded that middies could be caught cavorting in the corridors of a U.N.N.S. starship, even one still moored at Ganymede Orbiting Station.

If only I’d come down from the bridge a few seconds sooner I’d have been in time, but I’d been helping Ms. Dagalow enter the last of our new stores into the puter’s manifests.

Lieutenant Cousins was curt. “You too, Mr. Seafort.

Against the bulkhead.”

“Aye aye, sir.” I stiffened to attention, eyes front, furious at my betrayal by a friend whose sense I’d thought I could trust.

Alexi Tamarov, the sweating middy at my side, was sixteen and third in seniority. When I’d first reported aboard, he’d considered challenging me but hadn’t, and we’d since become comrades. Now his antics with Sandy had gotten us all in hot water.

Across the gleaming corridor Ms. Dagalow’s eye betrayed a glint of humor as she pried the canister of shaving cream from Sandy Wilsky’s reluctant fingers. She passed it to Lieutenant Cousins. Once again, I wished she were the senior lieutenant; Mr. Cousins seemed to take undue pleasure in the ship’s discipline he dispensed.

Lieutenant Cousins snapped, “Yours, middy? Are you old enough to use it?” From close observation during the five weeks since I’d joined Hiberniaat Earthport Station, I knew that at fourteen Sandy had not yet made the acquaintance of a razor. That meant he had, um, borrowed it. From me, perhaps. At seventeen, I was known to shave, if rarely.

“No, sir.” Sandy had no choice but to answer. “It’s Mr. Holser’s.” I bit my lip. Lord God, that was all this fiasco needed: trouble with Midshipman Vax Holser.

Vax, almost nineteen, resented me and didn’t care if it showed, for he’d missed being first middy by only a few weeks. He was full-grown, shaved daily, and worked out with weights. His surly manner and ominous strength encouraged us all to give him a wide berth.

Lieutenant Cousins nodded to Mrs. Donhauser, whose outrage had subsided into wry amusement. “Madam, my sincere apologies. I assure you these children”–he spat out the word with venom–”will not trouble you again.” His look of suppressed fury did not bode well.

“No harm done,” Mrs. Donhauser said peaceably. “They were just playing–”

“Is that what you call it?” Mr. Cousins’s grip tightened on the canister. “Officers in a Naval starship, chasing each other with shaving soap!”

Mrs. Donhauser was unfazed. “I won’t tell you your duty, Lieutenant. But I will make it clear that I was not harmed and have no grievance. Good day.” With that she turned on her heel toward the passenger cabins, presumably to change her tunic.

For a moment Lieutenant Cousins was speechless. Then he rounded on us. “You’re the sorriest joeys I’ve ever seen! A seventeen-month cruise to Hope Nation, and I have to sail with you!”I took a deep breath. “I’m sorry, sir. It’s my responsibility.”

“At least you know that much.” Cousins’s tone was acid.

“Is this how you run your wardroom, Mr. Seafort?”

“No, sir.” I wasn’t sure it was the right response. Perhaps my amiable manner encouraged Sandy and Alexi to step out of line. Certainly they would never have done so under Vax Holser’s tutelage.

“I expect stupidity from these young dolts, but it’s your job to control them! What if the Captain had come along?”

Lord God forbid. If they’d squirted Captain Haag rather than Mrs. Donhauser, Alexi and Sandy would see the barrel, if not the brig. For good measure, the Captain might break me all the way down to ship’s boy. Mr. Cousins was right. I could think of no way to placate him, so I said nothing.

It was a mistake. “Answer me, you insolent pup!”

To my surprise, Lieutenant Dagalow intervened. “Mr. Cousins, Nick was on watch. He couldn’t have known–”

“It’s his job to keep his juniors in line!”

I did, when I was present. What more could I do? For some reason Ms. Dagalow persisted. “But they’re young, we’re moored to Ganymede Station, they were just letting off steam... “

“Lisa, take your nose out of the puter long enough to remember the rest of your job. We have to teach them to act like adults!” From another officer it might have been a blistering rebuke, but Mr. Cousins’s acid manner was well known to all, and she took no notice.

“They’ll learn.”

“When our shaving cream runs out?” Cousins glared at us with withering contempt before turning back to Ms. Dagalow.

“Consider that by the end of the cruise at least some of them should be fit to be officers. I grant you, it’s unlikely any of these fools will ever make lieutenant. But what if one of us is transferred out at Hope Nation? Do you want silly boys standing watch, fresh from shaving cream fights?”

“We’ve time to teach them. Nick will issue ample demerits.” I certainly would. Each demerit would have to be worked off by two hours of hard calisthenics. They’d keep Alexi and Sandy out of trouble for a while.

Lieutenant Cousins’s voice grew cold. “Will he?” A chill of foreboding crept down my rigid spine. “Nicky should never have been senior, we all know that.” Even Lieutenant Dagalow frowned at the blatant undercutting of my authority, but Mr. Cousins was oblivious. “He’ll wag his finger at them, as always.” That wasn’t fair; I’d kept wardroom matters from the attention of the other officers, as was expected. Except this once.

“Will you cane the two of them, then? After all, it’s a wardroom affair.”

“No, I’ll let Nicky handle them.” From the corner of my eye I saw Alexi’s shoulders slump with relief. Then Mr. Cousins added sweetly, “But perhaps I can teach Mr. Seafort more diligence.” He sauntered toward his cabin. “Come along, middy.”

A half hour later I stood outside our wardroom, jaw aching from my failed effort not to cry out, eyes burning from the stinging pain and mortifying humiliation Mr. Cousins had inflicted across the hated barrel.

I slapped open the hatch. Inside the cramped compartment Sandy and Alexi, on their beds, dared say nothing. I crossed slowly to my bunk, stripped off my jacket and laid it on the chair. With care, I eased myself onto my bed.

After a time Alexi said quietly, “Mr. Seafort, I’m sorry.

Truly.” As was the custom, Alexi called me by my surname even within our wardroom. After all, I was senior middy.

Only Vax Holser had the resources to ignore that tradition and get away with it.

I fought down a smoldering rage; it should have been Alexi who was caned, not I. “Thank you.” My thighs smarted with exquisite agony. “You should have known better, both of you.”

“I know, Mr. Seafort.”

I closed my eyes, trying to will away the pain. At Academy, sometimes, it worked. “Who started it?”

“I did,” they said in unison.

My fingers throttled the pillow. “Sandy, you first.”

“We were in the head, washing up. Alexi splashed me. I splashed back.” He glanced up, saw my face, gulped.

Skylarking, like cadets at Academy. “Go on.”

“After he flicked me with a towel I grabbed the shaving cream. He chased me so I ran outside, and I was squirting him when Mrs. Donhauser came out of the lounge.” I said nothing. After a moment he blurted, “Mr. Seafort, I’m sorry I got you into troub–”

“I’ll make you sorrier!” I sat up, thought better of it, eased myself back on my bunk. “No officer would look into the middy’s head to see how you behave. But running out into the corridor... Mr. Cousins is right; you aredolts.”

Alexi flushed; Sandy studied his fingernails.

Angry as I was, I wasn’t surprised that they’d frolicked like the boys they were. What else could be expected, even on a starship? One had to go to space young to spend life as a sailor, else the risk of melanoma T was too great. Unfortunately, aboard such an immense and valuable vessel as Hiber-nia,there was no room for youngsters’ folly.

I growled, “Four demerits apiece, for letting your foolishness get out of hand.” Severe, but Mr. Cousins would have given much worse, and my buttocks stung like fire. “I’ll write it as improper hygiene. Alexi, two extra for you.”

“But I started it!” Sandy’s protest was from the heart.

“You ran into the corridor, which should have ended it.

Mr. Tamarov chose to follow. Alexi, how many does that give you?”

“Nine, Mr. Seafort.” He was pale.

I growled, “Work them off fast, because I’m in no mood to overlook any offense.” Ten would earn him a caning, like I’d just been given; Alexi would have to be vigilant while he worked down his demerits. “Start now; you have two hours before lunch.”

“Aye aye, Mr. Seafort.” They scrambled out of their bunks. In a moment they’d slipped on shoes and jackets and departed for the exercise room, leaving me the solitude I’d sought. I rolled onto my stomach and surrendered to my misery.

“It’s time, Mr. Seafort.” Alexi Tamarov jolted me from my fretful dream, from Father’s bleak kitchen, the creaky chair, the physics text I’d struggled to master under Father’s watchful eye.

I shoved away Alexi’s persistent hand. “We don’t cast off ‘til midwatch.” Groggy, I blinked myself awake.

From the hatchway, Vax Holser watched with a sardonic grin. “Let him sleep, Tamarov. Lieutenant Malstrom won’t mind if he’s late.”

I surged out of my bunk in dizzy confusion. Reporting late to duty station would be a matter for Mr. Cousins, and after the incident two days prior, Lord God help me if I called his attention anew. I glanced at my watch. I’d slept six hours! In frantic haste I snatched my blue jacket from the chair, thrust my arms into my sleeves as I polished the tip of a shoe against the back of my trouser leg.

“Why do we bother waking you?” Vax sounded disgusted.

I didn’t answer; he left for his duty station in the comm room, Sandy Wilsky tagging behind him.

“Thanks, Alexi,” I muttered, and nearly collided with him in the hatchway. I scrambled into the circumference corridor and ran past the east ladder, smoothing my hair and tugging at my tie as I rounded the bend to the airlock. I’d barely reached my station when Captain Haag’s voice echoed through the speaker.

“Uncouple mooring lines!”

Lieutenant Malstrom returned my salute in offhand fashion, his eye on the suited sailor untying our forward safety line from the shoreside stanchion.

“Line secured, sir,” the seaman said, and by the book I repeated it to Mr. Malstrom as if he hadn’t heard. The lieutenant waved me permission to proceed.

“Close inner lock, Mr. Howard. Prepare for breakaway.”

I tried for the tone of authority that came so naturally to Hibernia’slieutenants.

“Aye aye, sir.” Seaman Howard keyed the control; the thick transplex hatches slid shut smoothly, joining in the center to form a tight seal.

Lieutenant Malstrom opened a compartment, slid a lever downward. From within the airlock, a brief hum, and a click.

He signaled the bridge. “Forward inner lock sealed, sir.

Capture latches disengaged.”

“Very well, Mr. Malstrom.” Captain Haag’s normally gruff voice sounded detached through the caller. The ship’s whistle blew three short blasts. After a moment the Captain’s remote voice sounded again. “Cast off!”

Our duties performed, Lieutenant Malstrom and I had little to do but watch while our side thrusters alternately released tiny jets of propellant in quick spurts, rocking us gently. Our airlock suckers parted reluctantly from their counterparts on the station lock. U.N.S. Hiberniaslowly drifted free of Ganymede Station. When we were clear by about ten meters I glanced up at Lieutenant Malstrom. “Shall we secure, sir?”

He nodded.

I gave the order. The alumalloy outer hatches slid shut, barring our view of the receding station. Lieutenant Malstrom keyed our caller. “Forward hatch secured, sir.”

“Secured; very well.” The Captain seemed preoccupied, as well he might. On the bridge he and the Pilot would be readying Hiberniafor Fusion. I felt a bit queasy as our weight diminished. We were slowly losing the benefits of the station’s gravitrons, and the Captain hadn’t yet brought our own on-line.

We waited in silence, each lost in his own thoughts. “Say good-bye, Micky.” Lieutenant Malstrom’s tone was soft.

“I already did, sir, back in Lunapolis.” I would miss Cardiff, of course, and aloft, the familiar warrens of Lunapolis. I would even miss Farside Academy, where I’d trained as a cadet three years ago. But Ganymede Station was another matter. It had been over a month since I’d cried out my regrets in an unnoticed corner of a service bar in down-under Lunapolis, and by now I was long ready.

The fusion drive kicked in. In the rounded porthole the stars shifted red, then blue. As the drive reached full strength they slowly faded to black.

We were Fused.

External sensors blind, Hiberniahurtled out of the Solar System on the crest of the N-wave generated by our drive.

“All hands, stand down from launch stations.” The Captain’s voice seemed husky.

I locked Seaman Howard’s transmitter in the airlock safe.

“Chess, Nick?” Lieutenant Malstrom asked when the sailor had departed.

“Sure, sir.” We headed up-corridor to officers’ country.

In the lieutenant’s bleak cabin, a windowless gray cubicle four meters square and two and a half meters high, Mr.

Malstrom tossed the chessboard onto his bunk. I sat on the gray navy blanket at the foot of the bed; he settled by the starched white pillow at the head.

“I’m going to learn to beat you,” he said, setting up the pieces. “Something I can concentrate on besides ship’s routine.” I smiled politely. I had no intention of letting him win; chess was one of my few accomplishments. At home in Cardiff I had been semifinalist in my age group, before Father brought me to Academy at thirteen.

We played the half-minute rule, loosely enforced. In the weeks since Hiberniahad left Earthport Station I’d won twenty-three times, he had won twice. This time it took me twentyfive moves. As was our habit we shook hands gravely after the game.

“When we get back from Hope Nation I’ll be thirty-five.”

He sighed, perhaps a trifle morosely. “You’ll be twenty.”

“Yes, sir.” I waited.

“What do you regret more?” he asked abruptly. “The years you’ll lose, or being cooped in the ship so long?”

“I don’t see them as lost years, sir. When I get back I’ll have enough ship’s time to make lieutenant, if I pass the boards. I wouldn’t even be close if I stayed home.” I didn’t dare tell him how strongly the ambition burned within me.

He said nothing, and I reflected a moment. “Thirty-four months, round-trip. I don’t know, sir. I tested low for claustrophobia, like all of us.” I risked a grin. “It depends whether it’s three years playing chess with you or being reamed out by Lieutenant Cousins.” For a moment I thought I’d overstepped myself, but it was all right.

Lieutenant Malstrom let out a long, slow breath. “I won’t criticize a brother officer, especially to one of junior rank like yourself. I merely wonder aloud how he ever got into Academy.”

Or out of it, I added silently. If only Mr. Malstrom had been the one assigned to teach us navigation. But his primary duties were ship security and passenger liaison. Judiciously, I said nothing.

I wandered back to the wardroom. Inside, Sandy Wilsky sat attentively on the deck, legs crossed. From his bed, Vax Holser scowled. “Well?”

With a shrug of despair Sandy blurted, “I don’t know, Mr. Holser.”

Vax’s eyes narrowed. “You’re not by some chance still a cadet? Have we a genuine middy who can’t find the munitions locker?”

I crossed to my bunk, ignoring the boy’s hopeful look. Vax was entitled to haze him a bit. We all were; Sandy was junior and just out of Academy.

“I’m sorry.” Sandy glanced to me as if for succor, but I offered none. A middy should know such things. I kicked off my shoes, flopped on my bed.

Vax demanded, “What’s the Naval Mission?”

Sandy took a hopeful breath. “The mission of the United Nations Naval Service is to preserve the United Nations Government of and under Lord God, and to protect colonies and outposts of human habitation wherever established. The Naval Service is to defend the United Nations and its–its..”

He faltered.

Vax glared, and finished for him. “–and its territories from all enemies, internal or foreign, to transport all interstellar cargoes and goods, to convey such persons to and from the colonies who may have lawful business among them, and to carry out such lawful orders as Admiralty may from time to time issue. Section 1, Article 5 of the regs.”

“Yes, Mr. Holser.”

Vax said, “It’s worth a demerit or two, Nicky.”

I made no answer. If Vax had his way, the juniors would spend their lives in the exercise room. Within the wardroom, only I could issue demerits, though Vax could make the middies’ lives miserable in other ways.

“Laser controls?”

“In the gun–I mean, the comm room.” The youngster wrinkled his brow. “No, it must be... I mean... “

Vax scowled. “How many push-ups would it take–”

A few push-ups wouldn’t hurt Sandy–we’d all been subjected to worse hazing–but Vax got on my nerves. He even had the boy calling him “Mr. Holser,” which I resented. By tradition, only the senior middy was addressed as “Mr.” by the juniors.

I snapped, “Laser controls are in the comm room. You should know that–were you asleep during gunnery practice?”

“No, Mr. Seafort.” A faint sheen of perspiration; now he had us both annoyed at him.

I made my tone less grating. “On some ships the lasers are in a separate compartment called the gunroom, which is also what old-fashioned ships call their middy’s berth.”

“Thank you.” Sandy sounded appropriately humble.

Vax growled, “He should have known it.”

“You’re right. Not knowing your way around the ship is a disgrace, Sandy. Give me twenty push-ups.” It was a kindness. Vax would have made it fifty.

Dinner, as usual, was in the ship’s dining hall rather than the officers’ mess. I sat at my place sipping ice water, waiting for the clink of the glass. When it came I stood with the rest of the officers and passengers, my head bowed. Captain Haag, stocky, graying, and distinguished, began the nightly ritual.

“Lord God, today is October 19, 2194, on the U.N.S. Hibernia.We ask you to bless us, to bless our voyage, and to bring health and well-being to all aboard.”

“Amen.” Chairs scraped as we sat. The Ship’s Prayer has been said at evening in every United Nations vessel to sail the void for one hundred sixty-seven years, and always by the Captain, as representative of the government, and therefore of the Reunified Church. Like crewmen everywhere, our sailors considered shipping with a parson to be unlucky, and any minister who sailed in Hiberniadid so in his private capacity.

Few ships had it otherwise.

“Good evening, Mr. Seafort.”

“Good evening, ma’am.” Mrs. Donhauser, imposing in her elegant yet practical satin jumpsuit, was the Anabaptist envoy to our Hope Nation colony.”Did yoga go well today?” She smiled her appreciation of my offering. Mrs. Donhauser believed that daily yoga would get her to Hope Nation sane and healthy. Her stated mission was to convert every last one of the two hundred thousand residents to her creed.

Knowing her, I had no reason to disbelieve it was possible.

Our state religion was the amalgam of Protestant and Catholic ritual that had been hammered out in the Great Yahwehist Reunification after the Armies of Lord God repressed the Pentecostal heresy. Nonetheless, the U.N. Government tolerated splinter sects such as Mrs. Donhauser’s. Still, I wondered how the Governor of Hope Nation would react if she succeeded too well in her mission. Like Captain Haag, the Governor was ex-officio a representative of the true Church.

Hiberniacarried eleven officers on her long interstellar voyage: four middies, three lieutenants, Chief Engineer, Pilot, Ship’s Doctor, and the Captain. We all took our breakfast and lunch in the spartan and simple officers’ mess, but we sat with our passengers for the evening meal.

Our hundred thirty passengers, bound for the thriving Hope Nation colony or continuing on to Detour, our second stop, had their informal breakfast and lunch in the passengers’ mess.

Belowdecks, our crew of seventy–engine room hands, comm specialists, recycler’s mates, hydroponicists, the ship’s boy, and the less skilled crewmen who toiled in the galley or in the purser’s compartments caring for our many passengers–took all their meals in the seamen’s mess below.

Places at dinner were assigned monthly by the purser, except at the Captain’s table, where seating was by Captain Haag’s invitation only. This month I was assigned to Table 7. In my regulation blues–navy-blue pants, white shirt, black tie, spit-polished black shoes, bluejacket with insignia and medals, and ribbed cap–I always felt stiff and uncomfortable at dinner. I wished again I could wear the uniform with Vax Holser’s confident style.

At his neighboring table Chief Engineer McAndrews chatted easily with a passenger. Grizzled and stolid, the Chief ran his engine room with unpretentious efficiency. To me he was friendly but reserved, as he seemed to be with all the officers.

The stewards brought each table its tureen of thick hot mushroom soup. We dished it out ourselves. Ayah Dinh, the Pakistani merchant directly across from me, sucked his soup greedily. Everyone else affected not to notice. Mr. Barstow, a florid sixty-year-old, glared as if daring me to speak to him.

I chose not to. Randy Carr, immaculate and athletic, wearing an expensive pastel jumpsuit, smiled politely but looked through me as if I were nonexistent. His aristocratic son Derek strongly resembled him in appearance, and copied his manner. Sixteen and haughty, he did not deign to smile at crew; what courtesy he had was reserved for passengers.

“I started a diary, Nicky.” Amanda Frowel favored me with a welcome smile. Our civilian education director was twenty, I’d learned. I’d thought her smile was for me alone, until I’d seen her offer it to all the other midshipmen and two of the lieutenants. Ah, well.

I focused on her comment. “What did you write in it?”

“The start of my new life,” she said simply. “The end of my old.” Amanda was en route to Hope Nation to teach natural science. It was common practice to have a passenger fill the post of education director.

“Are you sure you mean that?” I asked. “Doesn’t your new life really start when you arrive, not when you leave?”

I took a bite of salad.

Theodore Hansen cut in before she could answer. “Exactly so. The boy is correct.” A soy merchant, he was investing three years of his life to found new soy plantations with the hybrid seed in our holds. If all went well he’d be a millionaire many times over, instead of the few times he already was.

“No, Mr. Hansen.” Her tone was calm.”That would only be true if the voyage is a hiatus in life, just a waiting period before I get to Hope Nation and resume living.”

Young Derek Carr snorted with disdain. “What else could it be? Is this”–he waved a hand airily–”what you call living?”

His tone offended me but I had no standing to object.

Miss Frowel, though, seemed not to notice. “Yes, I call this living,” she told him. “I have a comfortable berth, lectures to arrange, a trunkful of holovid chips to read, enjoyable dining, and pleasant company to share the voyage.”

Randy Carr poked his son ungently in the ribs. The boy glared at him; he glowered back. Some signal passed between them. After a moment Derek said coolly, “Forgive me if I was rude, Miss Frowel,” not sounding greatly concerned.

She smiled and the conversation turned elsewhere. As I finished my baked chicken I closed my ears and imagined the two of us alone in her cabin. Well, it would be a long voyage.

We’d see.

“So you finally got something right, Mr. Seafort!” Lieutenant Cousins examined my solution on the plotting screen, rubbing his balding head. “But Lord God, can’t Mr. Tamarov even learn the basics? If he’s ever let loose on a bridge he’ll destroy his vessel!”

Mr. Cousins had us calculating when to Defuse to locate the derelict U.N.S. Celestina,lost a hundred twelve years ago with all hands. I checked Alexi’s solution out of the corner of my eye. He’d made a math error matching stellar velocities. Basically correct, except for the one lapse, but his omission could have been catastrophic. Perhaps Celestinahad foundered because of some careless navigation error. No one knew.

“I’m very sorry, sir,” Alexi said meekly.

“You’re very sorry indeed, Mr. Tamarov,” the lieutenant echoed. “Of all the middies in the Navy, I get you! Perhaps Mr. Seafort and Mr. Holser will inspire you to study your Nav text. If they don’t, I will.”

Not good; it was an open invitation to Vax Holser to redouble his hazing, and there was already bad blood between the two.I had nothing against hazing; we all had to go through it and it strengthens character, or so they say, but Vax took a sadistic pleasure in it that disturbed me. Naturally, as first middy, I’d hazed Alexi and Sandy myself. From time to time I’d had one or the other of them stand on a chair in the wardroom in his shorts for a couple of hours, reciting ship’s regs, or given extra mop-up duty for minuscule infractions.

As low men, they had to expect that sort of thing, and did. I decided to keep an eye open. I couldn’t wholly protect Alexi from Vax, who was second in seniority, but I could try to keep the brooding middy from going too far.

“Back to work.” With an irritable swipe, Mr. Cousins cleared Alexi’s screen and brought up another plot.

Of course, our calculations were only simulated, with the help of Darla, the ship’s puter. In reality Hiberniawas Fused and all our outer sensors were blind.

Our first stop was to be at Celestina,if we could find her without too much delay. She was but a small object, and deep in interstellar space. Then, after many months, we would drop off supplies at Miningcamp, sixty-three light-years distant, before completing our run to Hope Nation. But simulation or no, Lieutenant Cousins expected perfection, and rightly so.While the fusion drive made interstellar travel practical, the drive was inherently inaccurate by up to six percent of the distance traveled in Fusion. So, we aimed for a point at least six percent of our journey from our target system, stopped, recalculated, and Fused again, as a safeguard against blindly Fusing into a sun, which had happened at least once in the early days. During Fusion our external instruments were useless; we couldn’t determine our position until we actually turned off the drive.

I tapped at the keys. So many variables. Our N-waves traversed the galaxy faster than any known form of communication. Though the Navy talked of sending out messenger drones equipped with fusion drive, in practice it didn’t work well. The drones frequently disappeared, and no one knew just why. You’d think a puter could handle a ship as well as a mere human, but-”Pay attention, Seafort!”

“Aye aye, sir!” I squinted at the screen, corrected my error.

Anyway, engineering a fusion drive was so expensive, it made more sense for the Navy to surround it with a manned ship, to ferry passengers and supplies to our colonies as well as mere messages.

Perhaps someday, if the drones were perfected, our profession would be obsolete. It would be a shame. Ours was a glamorous career, despite the slight risk of developing melanoma T, the vicious carcinoma triggered by long exposure to fusion fields.

Fortunately, humans whose cells were exposed to N-waves within five years of puberty seemed almost immune, though there were exceptions. Even for adults going interstellar for the first time, the risks weren’t excessive, but they grew with each successive voyage. So, officers were started young, and crew men and women were recruited for short-”Daydreaming again, Mr. Seafort? If it’s about a young lady, you could go to your wardroom for privacy.”

“No, sir. Sorry, sir.” Blushing, I bent over the console, my fingers flying.

One way to determine our location was to plot our position relative to three known stars and consult the star charts in the ship’s puter. We could also calculate the energy variations recorded during Fusion and estimate the percentage of error that would result. This method gave us a sphere of error; we could be at any point in the sphere. Then we merely had to calculate what our target would look like and see if we observed anything that matched.

I don’t care what the textbooks say. Navigation is more art than science.

When nav drill was over at last, I chewed out Alexi and sent him to the wardroom with a chip of Lambert and Greeley’s Elements of Astronavigationfor his holovid.

2

The clock ticked against me. Blindfolded, I felt for the bulkheads, hoping not to trip over an unexpected obstacle. I groped my way to a hatch. Lockable from the inside, fullsize handle. That meant I was in a passenger’s cabin. I felt my way out to the corridor. I turned left, arbitrarily, and walked slowly, my arm scraping along the corridor bulkhead.

I sensed I was moving upward, almost imperceptibly. It meant I was coming to a ladder.

One of our training exercises was to figure out where we were, without sight. We’d be given a Dozeoff and would wake some minutes later, Lord God knew where. If we took too long to orient ourselves, we were demented. I suppose, if a ship’s power backups and all our emergency lighting failed at once, the drill could be useful. But I couldn’t imagine a situation that would cause that to happen.

I bumped into the ladder railing. It extended both up and down; that meant I was on Level 2, in passenger country.