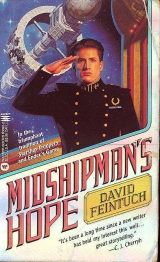

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

“I’m sorry, sir, but you’re a peasant,” Derek told me.

“You don’t understand dignity.” It started us going again.

This time when we stopped all was well between us.

“Come on, aristocrat, let’s inspect your estate.” We left the room and hurried down the stairs. “Just remember to play along,” I whispered at the last moment. Daringly, he punched me in the arm before we reached the main floor.

24

The helicopter swooped along the dense hedgerow marking the plantation border, while sprinklers made mist in the earlymorning light. We were exploring the more distant sections of the estate, having toured the main compound the evening before.

“How much wheat do you grow?” Derek had to shout above the noise of the motor.

“A lot.”

“No, how much?” Derek insisted. Fenn, in the pilot’s seat, pursed his lips.

I leaned across from the back seat. “Just say anything. He won’t know the difference.”

Fenn frowned at my insensitivity. “No, I’ll tell him. One point two million bushels, same as it’s been for years.”

Derek furrowed his brow. “Is that a lot?” Since dinner the previous night he had burrowed deep into his role.

Fenn smiled. “Enough. And then there’s six hundred thousand bushels of corn. And sorghum.”

“I like corn!” Derek said happily. I nudged him, afraid he would overdo it. “Nicky, why’d you poke me?” His tone was anxious. “Am I bothering him too much?” Nicky? I’d kill him.

“You ask too many questions, Anthony.”

“He’s no trouble,” Fenn said.

Derek’s look was triumphant. “See, Nicky?” He turned to Fenn. “Is this all yours and Mr. Plumwell’s?”

“Don’t I wish!” Fenn brought us down on a concrete pad outside a large metal-roofed building. “I work for Mr.

Plumwell, and he’s just the manager.” His tone changed.

“Course, he’s been here most of his life.”

“Doesn’t the owner live here?” I asked.

“Old Winston died six years ago, but he was sick long before that. This place was started way back, by the first Randolph Carr. He left it to Winston.”

“I take it he had no children.”

“Are you kidding? Five.” Fenn opened the gate. “They say his oldest boy was a heller. Randolph II. He gave the old man so much trouble Winston sent him all the way to Earth to college. He never came home while Winston was alive.”

Derek was attentive.

“Will he ever?” I asked.

“Randy was supposed to be on the ship that docked this week, and we expected we’d find ourselves working for him.

But he died on the trip, so it’s all up in the air.”

“What will happen?”

Fenn gestured toward the building we were about to enter.

“This is the second-largest feed mill on the planet. It’s entirely automated. Takes only three men to run it.” We looked in. “Randy had a son, some snot born in Upper New York.

They say he’s on the ship. The joeyboy’s never even been here, so he doesn’t know squat about planting. I guess he’ll be sent back to Earth for schooling. I don’t know; Mr. Plumwell’s made the arrangements. The joeykid won’t have any say until he’s twenty-two.”

“Then what?” A new tension was in Derek’s voice.

Fenn grinned. “Between you and me, boys, I wouldn’t be surprised if by that time Carr Plantation’s books were in such a state he’d need Mr. Plumwell more than ever.”

I grinned. “The Carrs should have stayed if they wanted to run the place.”

Fenn looked serious. “You’re lighter than you know.

Someday we’ll have a law about absentee owners. Sure, they’re entitled to profits, but a resident manager who stays all his life and runs things, he should have rights too. The management should pass down in his family, not the owner’s.

If–”

“Now wait a min–” Derek broke in.

I overrode him fast. “Anthony, don’t interrupt!”

“But he–”

“Haven’t you learned your manners?” I shoved Derek with force. “Apologize!” He looked surly. I squeezed his arm. “Go on!” Derek mumbled an apology, and I breathed easier. Perhaps when he calmed, he’d realize he’d nearly blown our cover.

Fenn asked, “Aren’t you a bit rough on the joey?”

“Sometimes he needs sitting on.” My tone was cross.

“His father let him believe he was too good for discipline.”

Derek shot me a deadly glance but kept quiet.

“You see how it is,” Fenn said. “Mr. Plumwell’s been here thirty years, and he knows every inch of this plantation.

Last year we cleared thirty million unibucks, even after the new acreage. Carr Plantation has to be run by a professional.”

“Where do you keep all the cash?” Derek was back in character.

Fenn smiled mirthlessly. “Some of it goes to the Carr accounts at Branstead Bank and Trust. The rest goes for salaries and expenses.”

“So the Carr boy gets to play with the money even if he can’t boss the plantation,” I said.

“Not quite. The account is in the Carr name but Mr.

Plumwell has control until a Carr shows up who has the right to run the estate. Mr. Plumwell makes sure the right people are on our side, that sort of thing. That money pool helps protect our way of life.” He looked at me closely. “How did we get on this subject?”

“I’m not sure.” My tone was bright and innocent. “What’s this conveyor belt do?”

That night we were invited to dine with Plumwell and his staff. I made a show of nagging Derek about his table manners; he retaliated by calling me “Nicky”. All the while Derek’s penetrating glance was taking in the oil paintings hanging above the huge stone fireplace, the fine china, the crystal glassware, the succulent foods and drink. He eyed Mr. Plumwell’s place at the head of the table with something less than delight.

In our room, after dinner, he moped on his bed while I got ready to turn out the light.

“What’s bothering you, Anthony?”

His voice was quiet. “Please belay that, Mr. Seafort.”

“What’s wrong, Derek?”

“This is my house. I should be at the head of the table.”

“Someday.”

“But in the meantime...” He brooded.”Fenn mentioned one point two million bushels of wheat. The reports they sent my father listed seven hundred thousand. Someone’s been skimming. Who knows what else Plumwell’s stolen? I’ve got to do something.”

“Why?”

He was surprised. “It’s my money.”

I had no sympathy. “You have your pay billet. Are you hurting?”

“That’s not the point,” he said with disdain. “Should this–this thief get away with what’s not rightfully his?”

“Yes, if he’s improving your estate.” He was shocked into silence. “You’re out of the picture, Derek. You’re so wealthy you won’t even miss what he steals. In the meantime, he’s opening up new acreage that permanently benefits your plantation. He’s doing a good job, stealing or not.”

“That’s easy for you to say,” Derek said bitterly. “You never had anything, and you never will!”

I snapped off the light, determined not to speak to him before morning. I yearned for the isolation of the Captain’s cabin.

Presently he said, “I’m sorry.” I ignored him, cherishing my hurt.

After a while he cleared his throat. “I apologize, Mr.

Seafort.” I made no answer. He snapped on the light. “Am I talking to the Captain now, or Mr. Seafort the ex-midshipman?”

A good question. In fairness to him, I wasn’t Captain at the moment. “The ex-midshipman.”

“Then I won’t stand at attention. I didn’t mean what I just said. I was angry and wanted to hurt you. Please don’t make me grovel.”

I relented. “All right. But I repeat what I told you. He’s doing a good job building Carr Plantation even if he does skim the profits.”

“What if I tell him who I am, just before we leave. That’ll show him he can’t–”

I felt a sudden chill. “Don’t even think about it, Derek.”

Thousands of uncleared acres adjoined the cultivated fields.

Some of them had hardly been explored.

He shivered. “Well, maybe not while we’re still here. But when I get back to town I’ll file suit.”

“No.”

“He can’t be allowed to get away with it. If I move fast I’ll save–”

“No, I said.”

“Why not?”

I was nettled. “Do you plan to stay on Hope Nation to fight a lawsuit?”

“I guess I can’t, unless you let me resign, but–”

“Get this straight, Mr. Carr! For the next four years you’re a midshipman in the United Nations Naval Service! You go where the Navy sends you. Understand? You took an oath, and a gentleman shouldn’t need reminding. The life you see here–it doesn’t exist yet.”

“But–”

“This is a form of time travel. Perhaps someday you’ll live here and worry about your riches, but not now. I took you on a visit to the future. You can’t touch anything and nobody can hear you!” There was silence. “Understand?”

He didn’t answer. I rolled over and snapped off the light.

Presently I heard Derek Anthony Carr, scion of the Hope Nation Carrs, cry himself to sleep after his Captain’s tonguelashing.

In the morning I felt guilty for having spoken so sharply.

We brought our duffels down to breakfast. I had Anthony thank everyone in sight. Even Plumwell smiled as we tooled down the drive in our electricar.

“Now what?” I asked when we were out of sight.

Derek’s tone was petulant. “I’ve seen enough plantations, if I won’t be–” His fingers drummed on the armrest; when he spoke again his voice was subdued. “Sorry, sir. Do you still want to take me to the Venturas?”

“Yes.”

“I think I’d like that.”

We headed back to Centraltown, camping once along the way. By the time we were back Derek was in good spirits, and I found to my surprise I’d begun to miss the organized bustle of shipboard life.

I decided to shuttle up to Hiberniafor a couple of days before leaving for the Ventura Mountains; Derek opted to stay in Centraltown. The peasant and the aristocrat parted company with awkward shyness.

I changed back into Navy blues and tried to tame my wild hair before checking in at Admiralty House. Forbee confirmed that there was still no interstellar Captain in the Hope Nation system. Unless Telstarunexpectedly appeared, none was scheduled to arrive for another five months. In the meantime they’d radioed all local vessels to ask for lieutenants and midshipmen. If none volunteered, Forbee would simply assign me the necessary officers, and leave the local fleet shorthanded.

After boarding, I took a luxurious hot shower in my cabin, ran all my clothes through the sonic cleaner, and hunted up a barber on Orbit Station. Hair trimmed back to my normal Navy length, I felt a new man. I roamed my empty ship as if looking for something, but I knew not what. Vax, when I stumbled over him, greeted me like a long-lost brother. He too found the ship’s silence eerie and disturbing. I even unbent so far as to try a game of chess with him, to his delight. He was no match.

Vax had learned through the grapevine that I would remain with Hibernia.To my astonishment he was pleased rather than apprehensive. I’d have thought he had more sense than to look forward to a cruise with an unqualified Captain who had my peculiar emotional disabilities. I didn’t remind him that depending on what officers were reassigned to Hibernia,he might be transferred out as a replacement. Time enough for that if it happened.

Depressed and not knowing why, I took the next scheduled shuttle back down to Centraltown. Customs and quarantine waved me through; by now I’d become a regular. Small-town life was amazingly relaxed compared, say, to Lunapolis.

I still had two days before I was to meet Derek for our trip to the mountains. I toured downtown Centraltown, explored the local museum, and ate in two of the recommended restaurants, occasionally encountering crewmen and former passengers. I stayed overnight in a prefab inn with the usual plastic furniture and decor. I bought a newschip and stuck it in my holovid; on page three was an announcement of an Anabaptist revival meeting in Newtown Hall. Mrs. Donhauser wasted no time. I thought of attending, but decided I didn’t care to meet her in her professional capacity.

Thoughts of our passengers reminded me I’d promised to look up Amanda Frowel. I immediately decided against it.

Then I spent the best part of an afternoon wandering aimlessly up and down the streets, arguing with myself. Sheepishly, I dug her address out of my duffel. After dinner I strolled across town to the address she had given.

“Nicky!” An apron around her waist, she smiled happily through her screen door, old-fashioned and domestic, inflicting a pang of regret that I soon had to leave the colony.

“Come in!” Her home was the back half of a comfortable wood house on a quiet side street on the edge of town. She rented, so help me, from a widow trying to make ends meet.

“I was just passing by,” I mumbled, sounding an idiot.

“But I was hoping you’d come. Look, my books are all over the place!” She brushed aside a pile of holovid chips scattered on a table. “I started work three days ago. Know what? They don’t want me just to teach natural science; I’m supposed to set up the whole science curriculum! They’ve never had one, isn’t that ridiculous?”

“Hasn’t anybody been teaching geology and biology?”

“Sure, but not in any organized way. They just got people who knew their subjects to come in and talk about them. Isn’t it quaint?”

“Very.” My tone was sour. Our world aboard Hiberniaseemed light-years away.

“Would you like to take a walk? I’ll show you the school.”

She was so enthused I agreed to go, wishing I hadn’t come to visit. She threw on a light jacket against the evening cool, and we set out for the school, about a mile away. She chattered with animation at first, but after a while she sensed my mood and grew quieter. We walked, hand in hand, under two moons. Their crossed shadows began to make me dizzy.

The public school was a one-story building encased in sheet metal, apparently a popular local building material. Amanda unlocked the door and took me inside. “This is where I work.” She showed me a classroom. The consoles at the student desks struck no chord of recognition, as my own schooling was at home with Father. Amanda’s desk and master console were to one side, where she could watch both the large screen and the students.

“The new term starts in three weeks. Nicky, it’s so exciting! The joeys will be so different from northamericans.”

“You think so?”

“Wouldn’t they, growing up in such a wild, free place?”

“I suppose.” I was feeling more and more depressed.

“Amanda, I have to go. I have an appointment.”

“You couldn’t stay awhile?” Her voice was wistful. My chest ached.

“Come, I’ll walk you home.” I wanted to leave and stay at the same time. On ship I’d never felt so bumbling and awkward with her. We walked mostly in silence through the darkened streets; Major had set and only Minor remained to guide us.

She hesitated, in front of her rustic home. “Will I see you again before you leave?”

“I don’t think so. I’m taking Derek to the Venturas tomorrow, then I’ll have to go back aboard.” I hadn’t mentioned I was still in command.

“Lieutenant Malstrom promised to take you there, didn’t he?”

“Yes.” I was grateful she remembered.

“Oh, Nicky.” Gently, she kissed the back of my hand.

“Life isn’t the way we plan it.”

“No,” I said miserably. I forced myself to smile. “Goodbye, Amanda.”

“Good-bye, Nicky.” We looked into each other’s eyes before she turned to go. As if in astonishment, she said, “We’ll never see each other again.”

“No.” I couldn’t stop looking at her.

“Well... good-bye, then.” She crossed her yard.

“Amanda?”

She stopped. “What is it?”

“Nothing. I–nothing.” As she opened her door I blurted, “Would you like to go with me?”

“To the mountains? I can’t, Nicky. I have a job.”

“I know. I thought maybe somehow–”

“School starts in three weeks. If I don’t have my curriculum ready... “

“They’ll fire you?”

She giggled. They’d waited three years for her; it would take three more to send for a replacement. “They won’t be very happy.” She frowned. “But I don’t care. I want to see the Ventura Mountains.”

“Really?” I said stupidly.

“With you. I want to see them with you.”

My eyes stung. I felt light-headed and miserable all at once. I ran to her and we embraced. “You’ll really go? God, can we start now?”

“Give me the night to get ready. And I have to explain to Mrs. Potter.” After a while she managed to get me to leave.

Derek didn’t seem put out when I told him I’d invited Amanda. He helped me buy a second pup tent and load the extra food and other supplies in the jet heli we’d rented. I had to promise the heli service three times not to tamper with the transponder; Captain Grone’s disappearance must have made them skittish.

We took off for the Western Continent shortly after breakfast. I was the only licensed driver; they’d taught us helipiloting at Academy but Derek and Amanda had never learned.

The permabatteries had ample charge for months. From time to time I turned on the autopilot to lean back and rest my eyes. The craft was roomy enough for Derek and Amanda to switch seats; they did so several rimes before settling down.

At four hundred fifty kilometers per hour it took us more than eight hours to reach the western shore. The huge submarine trees growing from the bottom of Farreach Ocean sent probing tentacles to the surface to absorb light. Plants somewhat like water lilies floated on the surface, rising and falling with the swells. The ocean was a vast liquid field of competing vegetable organisms.

The jagged spires of the Western Mountains loomed on the horizon long before we reached the continent; their raw power was breathtaking. The low hills and gently sculpted valleys of the Eastern Continent were tame compared to the vigor of these much younger peaks.

Derek pored over the map. “Do you want an established campsite or should we find a place of our own?”

“Let’s find someplace,” I said. Amanda nodded agreement. The cleared campsites would be remote enough, but we had no need to settle for them. Even after a hundred years, there were places in the continent no foot had trod.

Western Continent had settlements, far to the south, but here in the northern reaches virgin forests covered the sprawling land. At the coast, phalanxes of hills plunged to the sea to bury themselves in the swirling foam. Farther inland, great chasms cowered beneath the bristling peaks of the Ventures.

The heli service had marked some of the more spectacular sights on our map. Taking bearings from nav satellites I headed west over dense foliage.

As dusk neared I set us down on a grassy plain high in the hills. To one side was deep forest; a hundred feet beyond, the plain gave way to steep hills running down to a green and yellow valley. Across the vale a peak thrust upward so steeply that little grew on it. Waterfalls tumbled from the creases in the hill.

We got out the three-mil poly tents and their collapsible poles. I helped Derek pound stakes into the soft earth. We clipped the thin, tough material across the poles, and the tents were ready. Amanda began trundling in our gear.

Derek brought the micro and the battery cooler from the heli. He delved into the cooler and emerged with softies.

While I downed mine in two long swallows, he kicked at the grass. “How about going really primitive?”

I asked, “How?”

“A bonfire.” A heady thought. In Cardiff, as in most regions of home, wood was scarce and pollution so great that hardly anyone could get a permit to burn outdoors. Even the flue over Father’s hearth had its dampers and scrubbers.

Here, we need have no such concerns, as long as we were careful. I began clearing space for a fire.

The tough native grasses didn’t pull out easily; it took a shovel to dig them out. Their shallow intertwined root system ran just below the surface, and I had to spade to break the roots free.

Derek and Amanda returned from time to time with armfuls of firewood. I wondered if they intended our blaze to be seen from Centraltown. Our work kept us warm in the chill of the upland evening, but when we finished we immediately built up the fire.

I fed the flames from my cushion near the pit, while Derek and Amanda consulted on dinner like two master chefs sharing a kitchen. It pleased me that they liked each other.

We ate at fireside under the gleam of two benevolent moons. In the dark of the night, the crackling of the fire and the muted splashing of the waterfall across the valley were our only sounds. Knowing there were none, still I listened for insects and birds calling in the night.

Hope Nation seemed too silent. I knew our ecologists were preparing to introduce a few bird species and selected terrestrial insects. Bees to pollinate crops the old-fashioned way, for instance.

“It’s beautiful, Nicky.” Amanda sat between us. We’d devoured our dinner and were lazing around the campfire.

Our once mighty stacks of wood were fast diminishing, but they’d last until bed.

I tossed twigs into the flames. “What will people make of it when they settle here?” “They wouldn’t ruin a place like this.”

I snorted. “You should see Cardiff.” I’d seen photos of home in the old days, before the disposal dumps and treatment plants and the litter of modern civilization had improved the terrain. Still, the picturesque old smelters remained, some of them, as ruins.

I moved closer to the fire, watching my handsome midshipman’s face as he chatted with Amanda. Odd feelings stirred, recalling Jason, eons past. I shivered, wrenched myself back to reality. “Have you camped out with a friend before, Derek?”

He laughed. “On the rooftops of Upper New York?”

We stared into the firelight.

After a time he said to the flames, “I’ve never had a friend before, Mr. Seafort.”

I didn’t know how to answer. In Cardiff I had companions my own age. Together, we ran in the streets and got into mischief. Father, vigilant about my own behavior, grudgingly accepted my choice of associates. Jason and I were especially close, until the football riot of ‘90.

The silence stretched.

“Mr. Seafort, I want you to know.” Derek’s voice was shy. “This was the best day of my whole life.”

I could think of nothing to say. Not knowing what else to do, I reached out and patted his shoulder.

After a while Amanda yawned, and I found myself doing the same. “A long flight. I’m ready for bed.” I stood, and Amanda gathered her blanket.

An awkward moment. Amanda and I took a step toward the larger tent but stopped, embarrassed. Derek pretended not to notice. Hunching closer to the fire he peeled off his shut in its warmth. I tugged Amanda’s hand, gesturing toward our tent. On impulse, she let go my fingers, crossed to Derek.

She leaned over him and kissed him on the cheek. In the flickering light I saw him blush right up to the roots of his hair. “G’night.” He fled to his tent.

Smiling, I followed Amanda into our own shelter. We began taking off our clothes, poking and jostling each other in the closeness. I shivered when my skin touched the cold foam mattress. Amanda crawled in beside me.

Perhaps it was the first night in the exotic wildness of Western Continent. Aroused as never before, I tried to possess Amanda absolutely. My fingers and tongue roamed, caressing, probing, stroking, taking her warmth and making it mine.

I sucked greedily at her juices, her feverish hands guiding me gently. When at last I entered her it was as if I had become whole, our bodies thrusting desperately for fulfillment in simultaneous passion.

When it was over I lay drained of everything, feeling her heartbeat subside slowly against my ear. We rested, but again and again in the night we were like wild animals, coming alive to the frenzy of youth and desire. When morning came at last I slept in Amanda’s arms, peaceful, comforted, sated.

Whole.

It was never so fine again. Perhaps the newness was gone; perhaps some subtle tides failed to mesh. In the stillness of the nights we came together, loving, tender, eager to satisfy.

What we gave each other was good, and pleasing. But the first night remained a loving memory, never equaled.

Derek surely knew what we were experiencing. At least he must have heard Amanda cry out. But during the daytime we were a warm and friendly threesome, enjoying each other’s company, relaxing together. Only when dark fell did the two of us shyly retreat to our haven while Derek crawled into his solitary cot.

A dawn came when, Amanda’s head resting lightly on my shoulder, I woke with sadness, knowing our togetherness was drawing to a close. Amanda stirred in her sleep. As quietly as I could I slipped out of bed, gathered my clothes and crept out of the tent.

It was bitter cold; I threw some sticks on the embers and was at last rewarded with a sputtering flame. I fed it until it provided some warmth. I put a cup of coffee in the micro and when it heated, I held it between my two hands inhaling its vapor.

Restless, I wandered beyond the edge of the campsite toward the lightening sky, found a place to sit at the crest of a hill looking down into the valley below. Sipping my blessedly hot coffee I watched a moody yellow sun hoist itself over the peaks opposite, casting roseate hues on the bleak gray of dawn. The fog in the valley below began to lift. Across the glen, an eleven-hundred-foot waterfall threw itself endlessly over the cliff into the waiting valley.

Never had I seen a place so magnificent. Dawn brightened into day. Below, a smaller falls became visible as the night mists evaporated. The greens, yellows, and blues of the foliage brightened into their daytime splendor.

I had to leave this peaceful planet, and with it, Amanda. I must sail on to Detour, return briefly to Hope Nation to board passengers, then endure the long dreary voyage home to face an unforgiving Admiralty at Lunapolis. I knew they’d never give me command again. I knew I would never again come to this place. I knew I would lose Amanda to light-years of forgetfulness.

It was my lot to be banished from paradise.

Overwhelmed by despair amid the stark beauty of the Venturas, I mourned for Sandy Wilsky, for Mr. Tuak, for Captain Malstrom, for Father lost forever in his dour hardness. For the beauty I hadn’t known and would never know again. I cursed my weakness, my pettiness, the lack of wisdom that made tragedy of my attempt to captain Hibernia.Then Amanda, sweet Amanda, came from the glade and enveloped me in her arms, caressing, hugging, rocking, lending me solace only she could give.

After a while we walked together back to the campsite, my soul clinging to the gentle warmth of her touch. Derek, wearing short pants, shirtless, was just starting off to the stream with a bar of soap. Seeing us, he went on his way, mercifully silent.

“Micky, those terrible events on Hiberniaweren’t your fault.”

I sat brooding near the firepit, waiting for the micro to heat my coffee. “No? My talent is to hurt people. I killed Tuak and Rogoff; you know it wasn’t necessary. At Miningcamp I killed the rebel Kerwin Jones and his men, yet made a deal to spare his cohorts on the station. What was the difference?” “You’re too harsh on your–”

“I was cruel to Vax for months. I sent poor Derek to the Chief to be caned for nothing at all. Even Alexi–if I’d been a better leader I wouldn’t have had to send him to the barrel.

The way I treated the Pilot I can’t even discuss. I think of them all the time, Amanda. Lord God, how I hate being clumsy and incompetent!”

“You’re not, Nicky.”

“Tell that to Sandy Wilsky.” My tone was searing.

She was silent for a time. “Must you always do everything right?”

“Not always. But I’m talking about losing my ship and killing my midshipmen and brutalizing the crew!” Again the miasma of despair closed about me.

Amanda sat near, her arm thrown across my shoulders.

“You’ve done your best. Give yourself peace.”

“I don’t know how.” I lapsed silent until Derek returned, his skin pink and briskly scrubbed.

“Man, that’s cold!” He plunged into the firesite and stood warming himself by the flames. He glanced at me with concern. “Are you all right, Mr. Seafort?”

“Fine.” With an effort I lightened my tone. “What would you people like to do today?” It was to be our last full day in Western Continent.

Over breakfast, we decided we’d hike across the valley to the waterfall. I packed my backpack and set out with the others, hoping physical exertion would help banish my melancholy.

It took only a couple of hours to descend our side of the slope. But the valley was wider than it had appeared from the heights, and we had to pick our way among fallen trunks and viny growths that fastened to every crack. At last, weary, we reached the far side of the glen. A short hike brought us to the base of the waterfall where, to our delight, a pool was hidden in the dense undergrowth. Hot and sweating I began to strip off my clothes. After a moment Amanda did likewise.

Derek hesitated, ill at ease.

“Come on, middy! It’s no different from the wardroom!”

My annoyance was evident. His shyness was from his aristocratic past, not his Navy present. Perhaps, groundside for three weeks, he’d forgotten he shared a bunkroom, head, and shower with Paula Treadwell and the other middies.

Blushing, he took off his clothes and waded in.

I’d forgotten how wonderful were simple pleasures. A cold swim after our long hot exertion had a marvelous restorative effect. We cavorted and splashed like small children until our energy was spent. Finally we dressed, had a snack from our packs, and prepared to go back.

“Hey!” Derek pointed to the ground at the pool’s edge, where a sandaled footprint was outlined in the mud.

“We’re not alone.” Amanda was crestfallen.

I said, “Just some other tourists.” They’d come to see the spectacular waterfall, as we had.

“We didn’t see anyone.”

“They’re not here now,” I said impatiently. “Who knows how long ago they left that footprint?”

Derek stared at the mud. His voice was quiet. “It rained hard two nights ago.” The hairs rose on the back of my neck as my imagination brought forth an alien creature sipping water from this very pool. Then I laughed at my foolishness.

Aliens wouldn’t wear sandals like our own.

“So, someone else is around,” I said. It didn’t matter.

Derek jumped up with enthusiasm. “I’ll bet they’re down there!” He pointed to a wooded area past an open field farther down the valley. “Let’s find them!”

I didn’t want to disturb the other group’s privacy, but I had little choice but to follow unless I asserted my authority and demanded that we turn back. My sour mood returned. We scrambled across rocks and through broad-leaved vines until we reached the thicket. We walked along the edge of the field toward the woods.