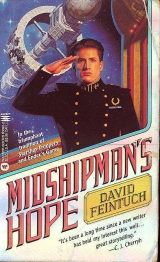

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

No matter how good the pay was, the recruits would have to wait years before they could spend it.

Guaranteed enlistment helped fill the crew berths. So we had men like Mr. Tuak, barely more civilized than the transpops, who responded to the guarantee they would be accepted and the half year’s pay issued in advance as an enlistment bonus.

Yet Tuak hadn’t done anything more than get caught up in a riot. Well, a little more; he had smuggled in the still that caused the riot in the first place. And he’d been fighting to protect the still from the men who wanted to dismantle it. But should he be put to death for that? “Mr. Tuak.” I waited while his excuses ran down. “Mr.

Tuak, the master-at-arms will take you back to the brig. You will be informed.” I slapped open the hatch.

“I din’ mean no harm, Captain. Listen, Captain, I got two crippled sisters at home with my mother. Ask the paymaster, my pay all goes to them, every bit of it. They need me.

Listen, I can stay out of trouble, honest, Captain!”

Vishinsky slapped the cuffs on his wrists, manhandled him out to the corridor.

“No more fighting!” Tuak said desperately, over his shoulder. “I swear!”

I was no closer to a decision.

As I left the dining hall after dinner the Purser handed me a sealed paper envelope. Unusual, in these days of holovid chipnotes. I took it back to the bridge to open. A letter, handwritten in a laborious script, obviously rewritten more than once.

Hon. Captain Nicholas Seafort, U.N.S.Hibernia Dear Sir:

Please accept my apology for the way I behaved when you visited my cabin. You are the authority on board this vessel. I owed you respect which I failed to offer. I was inexcusably rude to use the tone of voice I did.I didn’t know what to make of that. I read on.

When I thought about my discourtesy, I saw why you don’t think me fit for the Naval Service. I ask you to forgive me. I assure you I am capable of decent manners and I will not be offensive to you again.

Respectfully, Derek Carr.

Now that was laying it on a bit thick. I could believe that Mr. Carr had decided he’d been rude. It was possible that he might even apologize. But that he’d grovel was hard to swallow. I wondered why he’d done it. I locked the letter in the drawer under my console.

Some hours later I waited in the empty, dimly lit launch berth. The hatch opened and a head peered in.

“Over here, Mr. Holser.”

Vax looked around the huge cavern. Seeing me, he came quickly to attention. “Midshipman Holser reporting, sir!”

“Very well.” I indicated the cold open space. “What is this, Vax?”

He said, puzzled, “It’s the berth for the ship’s launch, sir.”

“That’s right. Now that it’s empty it’s a good time to clean it.” From my jacket pocket I took a small rag and bar of alumalloy polish. “I have a job for you. Clean and polish the bulkheads, Mr. Holser. All of them.”

Vax stared at me with anxiety and disbelief. The berth was huge; polishing it might take most of a year. It was utterly unnecessary work; one didn’t hand-polish the partitions of a launch berth.

“You’re assigned to this duty only, until it’s finished.

You’re off the watch roster and you’re forbidden to enter the bridge. You may begin now.” I thrust the polish and rag into his hands.

I had deliberately made it as hard as I could. By removing him from the watch roster and forbidding him access to the bridge, Vax would not again have opportunity to protest or ask my mercy. On the other hand, I’d given him a direct order. I hoped he would pass the test.

“Aye aye, sir.” His voice was unsteady, but he turned to the partition, rubbed the bar against the alumalloy. He began to polish it with the rag. Alumalloy doesn’t polish easily; it was hard work. After a few minutes of labor he had finished a patch a few inches around. He rubbed the bar of polish onto the adjoining spot and folded the rag to a clean surface. His muscles flexing, he rubbed the rag against the tough alumalloy surface.

I watched for several minutes. “Report for other duties when all four bulkheads are done.” I turned and walked to the hatch twenty meters from where he had started. I glanced behind me; he was hard at work. I slapped the hatch open, started through it. He kept polishing.

I stepped back into the launch berth. “Belay that order, Mr. Holser.”

“Aye, aye, sir.” His eyes darted from the bulkheads to me, and back, slowly taking in his reprieve.

I walked back to where he stood. “Vax, what did I demonstrate to you?”

He thought awhile before answering. “The Captain has absolute control of the vessel and the people on it, sir. He can make a midshipman do anything.”

“But you already knew that.”

“Yes, sir.” He hesitated. “But not as well as I know it now.”

Thank you, Lord God. It was what I’d prayed to hear.

“I’m canceling your special orders to report every four hours.

You may resume your wardroom duties. You know what I expect from you?”

“Yes, sir. No hazing, under any circumstances.”

“Don’t be ridiculous!” I was angry. If that’s all he had learned, all this had been a waste of time.

“I thought that’s what you wanted, sir. For me to control myself.” He was puzzled.

“Yes, that. And more. Come, let’s go raid the galley.”

He had to smile at that. At the beginning of the cruise, the four of us would occasionally sneak into the galley late at night and raid the coolers. We would catch hell if we were caught; that made it all the more attractive.

Now I entered the galley with impunity. The metal counters were shiny clean; the food was securely wrapped and stowed.

I opened the cooler and found some milk. Synthetic, of course. In the bread bin was leftover cake that would have gone to next day’s lunch. Well, they’d never miss it. I served my midshipman and myself. I indicated a stool for Vax; we ate off the counter. “It tasted better the other way,” I said.

“Yes, sir, but I’m glad for it now,” he said politely. Our Vax had come a long way.

“Now, Vax. About hazing. You’re first middy. You’ve been too busy to spend any time in the wardroom, so you haven’t taken charge. But I want you to. And with a change of command there will be some settling in. You’ll have to make sure they both know who’s senior.”

“Yes, sir.” He listened attentively.

“So, you may use your authority. Hazing, as we call it.

What I want you to stop isn’t hazing, but your bullying. You enjoy hazing so much you let it get out of control. You’re to control the pleasure you take in it. Stop yourself from going overboard and being cruel. You told me once you’re not nice, that there’s nothing you can do about it. If that’s still true, go back and start polishing the launch berth until you can do something about it. I’ll wait.”

He swallowed. I think no one had ever talked to him like that before.

I added, “You’re better off with the rag and polish, Vax, if you’re not sure you’ll control yourself. I meant it when I said I’ll wait. If you tell me I can trust you and I catch you being cruel like you used to be, I’ll break you. I’ll make your life a living hell for as long as I’m in command, until you can’t stand any more. I swear it by Lord God Himself!”

Vax said very humbly, “Please let me think for a moment, sir.”

I gave him all the time he wanted. He studied his fists, clasped on the metal work counter. Vax was slow. Not stupid, not retarded. Slow to make up his mind. I appreciated the corollary of that. Once he made up his mind he was utterly dependable.

“Captain Seafort, sir, I think I can do what you want. I mean, 1 know 1 can, if I may ask a favor.”

“What favor?” This was no time to start bargaining.

“I know the senior middy is supposed to handle wardroom matters and keep the other midshipmen out of your hair. But if I’m not sure of myself, could I come and ask you if you’d approve? I mean, of a hazing?”

I could have hugged him. It felt as if a fusion engine had been taken from around my neck. “I think so,” I said soberly, after a moment’s reflection. “I would allow it, yes.”

“Thank you, sir. I promise I’ll control myself. I will haze the other middies only when I think it’s good for discipline.

I won’t let myself get carried away. Sir.”

“Vax, the wardroom is yours. I won’t spy on you; I accept your word. You have a job to do, and you’d better get on with it. Thanks to you, poor Alexi ended up over the barrel when all he needed was a lecture and a few hours of calisthenics.” That wasn’t fair; it was my fault more than Vax’s.

“I’m very sorry, sir. You can count on me now.”

I should have saluted and dismissed him. Instead, I broke regs, custom, and all propriety. Matters must have been getting to me. Slowly, looking him in the eye, I offered my hand. Just as slowly he took it in his big paw and clasped it firmly. We shook.

13

“Lord God, today is March 30,2195, on the U.N.S. Hiber-nia.We ask you to bless us, to bless our voyage, and to bring health and well-being to all aboard.” Seated, I nodded to my two tablemates. Weeks after I’d assumed command, Mrs.

Donhauser and Mr. Kaa Loa were still my only dinner companions.

The purser bent at my ear. “Sir, one of the passengers is asking if he may join the Captain’s table.” My popularity had just risen by half.

“That’s agreeable, Mr. Browning. Who is it?”

“Young Mr. Carr, sir.”

I hadn’t spoken to Derek in the weeks since his letter. I was curious. “Ask him if he cares to start tonight.”

A moment later Derek Carr approached with diffidence.

“Good evening, Captain. Mrs. Donhauser. And you, sir,”

this last to Mr. Kaa Loa, whom he apparently didn’t know.

“Please be seated, Mr. Carr.” I introduced the boy to the Micronesian.

After his courtesies to the older man Derek turned to me.

“Sir, I apologize again for my behavior in my cabin. I promise it won’t happen again.”

Where was all this heading? “No matter, Mr. Carr. It’s over and done.” Derek sat. I chatted with Mrs. Donhauser.

She turned the topic to religion, a difficult topic on board ship. Her Anabaptist doctrines were tolerated, as were most cults, but the Naval Service, like the rest of the Government, was committed to the Great Yahwehist Christian Reunification. She knew full well that as Captain I was a representative of the One True God, and she shouldn’t be baiting me. I assumed she was just out of sorts; normally Mrs. Donhauser was a pleasant if argumentative companion.

To avoid contention I turned to Derek. “How have you been occupying yourself lately, Mr. Carr?”

“I’ve been studying, sir. And exercising.”

Definitely a change in manner. I gave him another opening.

“Were you enrolled in school before the voyage?”

“No, sir. I had tutors. My father believed in solitary education.”

“We should reimpose mandatory schooling,” Mrs. Donhauser grumbled. “The voluntary system doesn’t work; we don’t have enough technocrats to run government or industry.

We’re constantly starved for educated people.”

“Mandatory education didn’t work either,” I said. “Literacy levels dropped constantly until it was abandoned.”

Mrs. Donhauser, savoring a good argument, launched into a vehement counterattack, demonstrating, at least to herself, that mandatory education was the only way to save society.

“Don’t you agree, Mr. Carr?” she asked when she finished.

“Yes, ma’am, I agree that a mass of uneducated people is a danger to society. As for the rest–” He turned to me. “Is she right, sir?” Now I was really puzzled. This was not the haughty youth who’d come aboard the ship. And I was likewise sure he had not undergone a complete change of heart.

His courtesy had a purpose. I turned away the question and studied him during the rest of the meal.

Going over watch rotations in my cabin that evening, I realized how little time I had to decide the fate of the three wretched sailors under sentence of death. I intended to make a deliberate decision; their fate wouldn’t be determined by default. Shortly, I would have to free them or allow–no, order–the executions to take place.

I had spoken to Tuak and Herney, but I’d put off seeing Rogoff because I found the interviews unbearable. I made a note to see the man after forenoon watch.

I undressed, crawled into my bunk, and drifted off to sleep almost immediately. In the early hours I awoke. I tossed and turned until I couldn’t stand it any longer; I snapped on my holovid and read ship’s regs. If they wouldn’t put me to sleep, nothing would.

Again I closed my eyes and tried to sleep; I’d never found insomnia a problem in the wardroom. At three in the morning I turned on my bedside light. My stomach slowly knotted from tension as I began to dress.

I walked the deserted corridors to Level 3. One of Mr.

Vishinsky’s seamen guarded the brig. He was watching a holovid, feet on the desk, when I appeared in the hatchway.

Horrified, he leapt to his feet and snapped to attention.

I ignored his infraction. At that hour, one need not be prepared for a Captain’s inspection. “I’m here to see Mr.

Rogoff, sailor.”

“Aye aye, sir. He’s in cell four. If the Captain will let me get the cuffs on him–”

“Not necessary. Open the hatch. And lend me your chair.

You don’t sit on guard duty anyway.”

“Aye aye, sir. No, sir.” He jumped to obey.

Rogoff, wearing only his pants, was asleep on his dirty mattress when the light snapped on. Bleary, he looked up as I entered and set down the chair.

“Mr. Rogoff.”

“Mr. Seafort? I mean, Captain, sir? Is it–oh, God, I mean, are you here to–” He couldn’t say the words.

“No. Not for a few days yet. I’m here to talk to you.”

“Yessir!” He scrambled to his feet. “Anything you say, Captain. Anything.”

I turned the chair backward and straddled it. “If I don’t commute your sentence they’re going to hang you. Tell me why I should pardon you.”

He rubbed his eyes, standing awkwardly in front of my chair. “Captain, please, for Lord God’s sake, let me go. Brig me for the rest of the voyage, or whatever you want. But don’t let them hang me. I didn’t mean any harm.”

“No harm?” I asked him. “You clubbed the CPO unconscious while Mr. Tuak held his arms.”

“Not in cold blood, sir. We were fighting, all of us.”

“You can’t brawl with a superior, even a petty officer.”

“No, sir, you’re right, sir. But the thing was, the fight started. Your blood gets hot, you don’t see what’s going on, or stop to think things over. Right then, Mr. Terrill was just another joe, you know? He wasn’t the CPO, he was just somebody to hit. It’s not like I meant to mutiny, sir.”

He had stated in a nutshell why the affair should have been handled at Captain’s Mast. Damn Captain Malstrom for leaving me this mess. I felt guilty for my anger, and it made me cross. “Maybe that’s so for the first blow, Mr. Rogoff.

But you smashed him several times in the face. By then you knew who you were hitting.”

“Excuse me, Captain, no offense, have you ever been in a fight?”

“Yes.” I hadn’t won.

“While you were swinging did you stop and think about the consequences? Did you consider how hard you should fight, or whether you should hit a joe?”

“I never swung against a superior officer, Mr. Rogoff.”

Except my senior middy when I was posted to Helsinki, and he blackened both my eyes and kneed me so hard I couldn’t walk upright for days. But that didn’t count, did it? Challenging the first middy was understood and accepted. I wasn’t like Rogoff, was I? “You kept punching him in the face.

Your superior.”

“Sir, look at me. Pretend it’s you here, in this god-awful place. You had a bad fight, and they’re going to hang you for it. Please. Don’t do that to me.”

I made my voice hard. “It wasn’t that simple, sailor. You were fighting to protect that bloody still of yours, to make sure the officers didn’t find it. You were covering up a crime Mr. Terrill was about to discover.”

Rogoff hugged himself. He looked at the deck, shaking his head from side to side. His bare feet wiggled nervously.

“Captain,” he said, looking up, “I ain’t no angel. I do things that ain’t right. I know I been in trouble before. But the still, that’s brig time or a discharge. If I’d of realized what I was doing I wouldn’t have touched him. You gotta believe that.”

“I believe you weren’t thinking about court-martial, Mr.

Rogoff. I can’t believe you were unaware you were hitting Petty Officer Terrill. Is your being excited reason to pardon you?”

“Captain, I beg you. I’m begging for my life.”

“Please, don’t.” I didn’t want that power over him.

“Look!” He dropped to his knees in front of me. “Please, sir, I’m begging. Don’t hang me! Let me live, give me another chance!”

I scrambled to my feet, sweating. I had to get out of the cell. “Guard!”

“Sir, I’m not evil!” He put his palms on the deck, abasing himself. “Please let me live! Please!”

I didn’t run out of the cell. I walked. I walked out of the brig anteroom. I walked to the turn of the corridor outside.

Then I ran, as if the devils of hell were at my heels. I tore up the ladder past Level 2 to officers’ country, past the bridge to my cabin. I fumbled at the hatch, slapped it closed behind me. I barely made it to the head before I heaved my undigested dinner into the toilet. I remained there, shaking with fear and disgust. It was when I realized that I was kneeling with both my palms on the deck that I began to cry.

I became a hermit, refusing to leave my cabin except for brief excursions to the bridge. I had the Chief cross my name off the watch roster. My look was such that no one dared speak to me. I took meals in my cabin, refusing even to take my evening meal in the dining hall with the passengers. I pretended to myself I was sick, that I felt feverish. I lay in my bunk imagining that I was safe, in Father’s house.

In the quietest hours of the second night I had a dream.

Again I was a boy, walking toward the Academy gates. My duffel was very heavy, so heavy I could hardly carry it. I had to say something to Father, but I couldn’t speak. He walked along beside me, dour and uncommunicative as always. Yet he was ther| with me, was that not enough proof he loved me?I changed the duffel to my other arm so I could put my hand in his. Father switched to my other side. I switched the duffel back, but he stepped around me once more. I prepared the words of parting I would offer. I rehearsed them over and again until they sounded right.

The gates loomed closer. Now we were at the broad open walk in front of the Academy entrance. The sentry stood impassive guard. I turned, knowing it was time to say goodbye. Father put his hands firmly on my shoulders and turned me toward the waiting gates. He propelled me forward.

In a daze I walked though the gates, feeling an iron ring close itself around my neck as I did so. I turned. Father was striding away. I willed him to turn to me. I waved to his back.

Never looking over his shoulder, he disappeared over the rise.

The iron ring was heavy around my neck.

I awoke, shaking. Eventually my breathing fell silent. I smelled the acrid sweat on my undershirt; I stripped off my clothes and walked unsteadily to my shower to stand under the hot water a long while, motionless.

When I finally dared go back to bed I slept untroubled. In the morning I ate the breakfast Ricky brought, and left my cabin to become a human being once more.

14

“Excuse me, sir, a question.”

“What is it, Vax?” We were on watch. In the long silence, I’d been trying to empty my mind of everything, to think of nothing. I was not succeeding.

“One of the passengers, Mr. Carr, asked if I would show him Academy’s exercise drills this afternoon. I thought I ought to have your permission first.”

I could see no reason to refuse. “If you want to, Vax, I have no objection.” I smiled. “Are you about to become a drill sergeant?”

“No, sir. I thought I’d do them with him.” I should have guessed.

Time passed. Still I made no decision about the prisoners.

The next day Yorinda Vincente asked to see me. I assented.

I didn’t want her on the bridge or in my cabin, so I met her in the passengers’ lounge.

“This is on behalf of the Passengers’ Council.” Her tone was stiff. “We want to know what will happen to the ship, I mean the crew, when we get to Hope Nation.”

“You’re asking if Hiberniawill get a new Captain?”

“And other officers, yes.”

“Most of you will disembark at Hope Nation, Ms.

Vincente. How does it concern you?”

“Some of us are booked to Detour, Captain Seafort. Other plans would have to be made.” She meant that they wouldn’t want to stay on the ship if I were going to sail her. I understood. / wouldn’t want to stay on the ship if I were going to sail her.

“Hiberniais under orders from Admiralty at Lunapolis,”

I explained. “My authority as Captain derives from those orders. Admiralty has a representative, Admiral Johanson, at Hope Nation. When I report, he will relieve me of command, appoint a commissioned Captain, and assign lieutenants to the ship.”

“Are there experienced officers at Hope Nation?”

“More experienced than I, Ms. Vincente. And even if there weren’t, the Admiral is my superior officer. I’m sure he’ll relieve me and appoint a Captain of his choosing. Hiber-niawill be in good hands when she leaves Hope Nation.”

She explored all the possibilities. “I imagine skilled officers aren’t sitting around Hope Nation waiting to be posted.

What will he do if he doesn’t have enough lieutenants?”

“It’s unlikely any Naval officers are sitting around waiting, Ms. Vincente. The Service is always shorthanded. What I imagine he’ll do is borrow them from local service, and replace them with some of our own officers. Perhaps even myself.”

“People without interstellar experience?”

“Not every lieutenant goes interstellar before he’s commissioned, ma’am. As long as the Captain’s a seasoned officer, the ship will be in good hands.” I continued my reassurances until she seemed satisfied.

The next day when I met Vax on the bridge I asked, “How are your exercises going?”

“They’re not,” he said. I raised an eyebrow. He added, “Derek showed up the first day and we worked out. Easy stuff, like they give the first-year cadets. Yesterday he came again, but after a half hour he walked out.”

“What did he say?”

“Nothing, sir. He just stalked out and slammed the hatch.”

So much for Mr. Carr.

I met Amanda in the corridor on the way to the dining hall.

She stopped, waiting for me to speak first.

“I haven’t made up my mind yet, Amanda.”

“Isn’t your time about up?”

“Day after tomorrow. One way or another, it will be over by then.”

“Listen to your conscience,” she said. “Pardon them.

Years from now you’ll hate yourself if you don’t.”

“I’m still thinking.” I didn’t mention my interview with Rogoff. We went in to dinner. When I came to the part of the Ship’s Prayer, “Bring health and well-being to all aboard,” I stumbled over the words.

That evening Chief Me Andrews sat down heavily in the armchair alongside my table. The pipe lay between us. I said, “Chief, I order you to ignite that device. We need to investigate it further.”

“Aye aye, sir.” It was his third visit to my cabin; we were establishing the form of a ritual. He opened the canister and got out his candlelighter.

I kicked off my shoes. After all, it was my own cabin. “I was hoping I’d have another middy by now.” I yawned.

“We’re all standing too many watches.”

“On the bridge or in the launch berth, sir?” He was beginning to unbend with me, just a bit.

“Oh, you heard about that?”

“Someone saw you take Mr. Holser in there and emerge later with a very subdued midshipman.”

“Who saw?”

“I don’t remember, sir.”

If we could power the ship by gossip it would be faster than fusion. Maybe it really was Darla who spread the word.

“I think Vax will be all right, Chief. I’ve straightened things out with him.”

“With a club?”

I smiled. “Vax just needs the facts demonstrated from time to time. Then he believes them. He’ll make a good first middy.”

He puffed on his artifact. “What you need, Captain, is a fourth middy. Maybe even a fifth.” I knew that. I could then make Vax a lieutenant. Probably also Alexi, if I hadn’t embittered him for life.

“The only feeler I’ve had is from that Carr joey, and I turned him down.”

“There’s Ricky.” The Chief knew everything.

“He won’t be old enough to be much help until we’re past Detour. We’ll have new officers and won’t need him by then.”

“So why’d you invite him, Captain?”

“I didn’t say he’d be no help at all. And I like him.”

“He’ll agree. He needs more time to think about it, but count on him.”

“I’m not so sure,” I said. “I don’t have the knack of persuading people without terrorizing them. First Vax, then the Pilot, and then Alexi. Now it’s Ricky. I had to scream at the top of my voice to stop him from standing at attention.

I’m lucky he didn’t wet his pants.”

The Chief smiled. “You didn’t terrorize him. You startled him some, but he’s told everyone belowdecks how the Captain wants him to be a midshipman. He sticks his chest out when he says it. I don’t think you have to worry.”

“Then I was fortunate. Part of my problem having no natural authority is that I come on like a wild man to uphold the stature of the office. As I did with Alexi.”

The Chief shrugged. “The barrel? He’ll get over it. I gave him half a dozen, not all that hard. He’s had worse before.”

“But not from me. I was his friend.”

Chief McAndrews took several puffs on the pipe before deciding to reply. “You still are,” he said. “You’ve done him a favor, whether he knows it or not. A big one. When we get to Hope Nation he’ll probably be transferred. What would happen to him if he had a silly fit on the bridge of someone else’s ship?”

I shuddered. Either he wouldn’t sit down for a month or he would find himself in the brig. If the Captain didn’t die of apoplexy first.

“Still, I should have found some other way to stop him.”

The Chief waved his pipe in the air. “Say you’re right, Captain. Maybe you should have found a better way. He’ll still get over it. Neither he nor anyone else has the right to expect you to be perfect. You’re doing your best.”

“And it isn’t good enough, Chief.” I stared moodily at his smoke. “In a couple of days I have to decide about those poor joeys in the brig. I have two choices, both wrong. If I let them go, mutiny goes unpunished. Admiralty would never pardon them if the affair had happened back at Earthport; they’d hang the three with no regrets. But I feel that if I execute them, I’m a heartless killer.”

I brooded. “Expect myself to be perfect? If I were barely competent I’d find a third solution. I’ve tried; I can’t think of any. So I’ll pick one alternative or the other. My best isn’t good enough.”

Wisely, the Chief said nothing.

The next day, I was restless and irritable. To distract myself I ran surprise drills throughout the ship, telling myself it was to improve the crew’s alertness. “Fire in the launch berth!”‘ ‘Fusion engine overheat!” ‘ ‘Man Battle Stations!”The crew scurried.

I announced that Darla had a nervous breakdown, and made the middies plot all ship’s functions by hand. They complied, although nobody, especially Darla, thought it was funny. I entered drill response times in the Log to compare with future drills. I made a mental note to have future drills.

All in all, I continued making myself unpopular.

I woke in the morning with a sense of dread at what I’d have to face before the day ended. After showering and dressing I sat to await the usual knock; in a few moments Ricky arrived with my breakfast. He put down the tray, saluted, and waited to be dismissed. Though he stood at attention, his stomach no longer tried to meet his backbone.

“Stand easy, Mr. Fuentes.”

“Thank you, Captain. They were having waffles and cream so I brought you extras. Cream is real zarky.” He looked wistfully at the tray. Crew rations didn’t compare with officers’ and passengers’ fare.

I liked the new Ricky much better. Or was it the old Ricky? “Thank you. About that cadet idea, what do you think?”

“Mr. Browning says I should. So does Mr. Terrill. It’s just I’m a little scared. Captain, sir.”

“I can understand that.” I took a bite of waffle. It was delicious. I thought of offering him some, but there were limits. A crewman didn’t breakfast with the Captain. “So you can read, hmm?”

“Oh, yes. I can write too. Even by hand.” He was very proud of it.

“Ricky, I’m going to arrange some lessons for you. Math, physics, history. I want you to work as hard as you can. Will you do that for me, as a special favor?” That would get his cooperation far better than an order.

He actually swelled with pride. His shoulders went up, his chest came out. “Oh, yes, sir. I’ll do my best.”

“Very well. Dismissed, Mr. Fuentes.” He saluted, spun on his heel, and went to the hatch. Someone must have been teaching him physical drills. I suspected the Ship’s Boy already knew more about Naval life, and how Hiberniawas run, than most people would imagine. “Oh, Mr. Fuentes?”

“Yes, sir?” He stopped in the entryway.

“Go to the galley. My compliments to the Cook, and would he please serve you a portion of waffles and cream.”

His face lit up. “Oh, thanks, Captain, sir! They’re real good. He already gave me some, but I’d love more!” He raced out into the corridor. So much for my generosity.

Sandy was on watch with the Pilot when I popped onto the bridge for a quick inspection. Mr. Haynes nodded with careful civility. He hadn’t had much to say to me since the incident with our coordinates.

I glanced at Sandy and my eyebrow rose; the boy was dozing in his seat. That wouldn’t do. I relieved him and sent him to Vax, with a request to encourage the youngster to stay awake on duty.

Vax, a middy himself, couldn’t send Sandy to the barrel, but he had ways to get the point across. I didn’t feel guilty this time; sleeping on watch was a heinous offense. I had to prepare Sandy to hold his own watch. It crossed my mind that I myself had dozed on the bridge only a couple of weeks before. I argued that I wasn’t actually watch officer; I’d just stayed to keep an eye on things. When part of me started to argue back, I left the bridge.

I wandered the Level 1 circumference corridor, past cabins in which Lieutenants Dagalow and Cousins once lived. Past Lieutenant Malstrom’s cabin where a lifetime ago I’d played chess. Through the passengers’ section, nodding curtly to anyone who noticed me. I looked into the infirmary. The med tech came to attention in the anteroom; Dr. Uburu was with a passenger in the cubicle that served as an examining room.