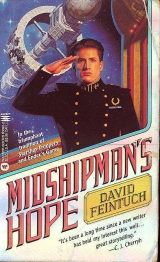

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Amanda’s cabin was somewhere near; as our friendship had progressed I’d finally been invited inside it.

Where was I, east or west? If east, there’d be an exercise room about twenty steps past the railing. I couldn’t remember what was west, except that it wasn’t the exercise room.

Throwing caution aside to improve my time I staggered down the passage. If Mr. Cousins had put a chair in the corridor I was done for.

No exercise room. “Passenger quarters, second level west, about fifteen meters west of the ladder, sir.”

“Very good, Nicky.” Lieutenant Malstrom’s voice. I took off the blindfold and blinked in the light. I grinned, and he smiled back. I could imagine how our first lieutenant would have said the same thing.

Cut out three foam rubber disks an inch thick, set them one on top of another, and stick a short pencil through the center.

Now stand the pencil on end. You’d have a rough model of our ship. The engine room was within the pencil underneath the disks; below that sat the drive itself, flaring into the wave emission chamber at the stubby end of the pencil.

We, crew and passengers, lived and worked in the three disks. The portion of the pencil above the disks would be our cargo holds, full of equipment and supplies for the colony on Hope Nation and for Miningcamp.

A circular passage called the circumference corridor ran around each disk, dividing it into inner and outer segments.

To either side, hatches opened onto the disk’s cabins and compartments. At intervals along the corridor, airtight hatches were poised to slam shut hi case of decompression; they’d seal off each section from the rest.

Two ladders–stairwells, in civilian terms–ascended from the east and west sections of Level 3 to the lofty precincts of Level 1. The bridge was on the uppermost level, along with the officers’ cabins and the Captain’s sacrosanct quarters I’d never been allowed to view.

Level 2 was passenger country, holding most of the passenger staterooms. A few passengers were lodged above on Level 1, and the remainder had cabins below on Level 3, where the crew was housed.

Passenger cabins were about twice the size of those given the lieutenants. Below, the Level 3 crew berths made even our crowded middy wardroom seem luxurious. Naval policy was to crowd us for sleeping but allow us ample play room.

The crew had a gymnasium, theater, rec room, privacy rooms, and its own mess.

The exercise over, Mr. Malstrom and I climbed up to Level 1. I had just time enough to get ready for my docking drill on the bridge. I showered carefully before reporting to Captain Haag. I still only shaved about once a week, so I had no problem there.

I dressed, tension beginning to knot my stomach. Though I was a long way from making lieutenant, I had no hope of eventual promotion until I could demonstrate to the Captain some basic skill at pilotage.

I gave my uniform a last tuck, took a deep breath, and knocked firmly on the bridge hatch. “Permission to enter bridge, sir.”

“Granted.” The Captain, standing by the Nav console, didn’t bother to turn around. He’d sent for me, and he knew my voice.

I stepped inside. Lieutenant Lisa Dagalow, on watch with Captain Haag, nodded civilly. Though she’d never gone out of her way to help me, neither did she lash out like First Lieutenant Cousins.

I couldn’t help being overawed by the bridge. The huge simulscreen on the curved front bulkhead gave a breathtaking view from the nose of the ship–when we weren’t Fused, of course. Now, the other smaller screens to either side were also blank. These screens, under our puter Darla’s control, could simulate any conditions known to her memory banks.

The Captain’s black leather armchair was bolted to the deck behind the left console. The watch officer’s chair I’d occupy was to its right. No one else ever sat in the Captain’s chair, even for a drill.

“Midshipman Seafort reporting, sir.” Of course Captain Haag knew me. A Captain who didn’t, recognize his own middies in a crew of eleven officers had problems. But regs were regs.

“Take your seat, Mr. Seafort.” Unnecessarily, Captain Haag indicated the watch officer’s chair. “I’ll call up a simulation of Hope Nation system. You will maneuver the ship for docking at Orbit Station.”

“Aye aye, sir.” It was the only permissible response to an order from the Captain. Cadets or green middies fresh from Academy were sometimes confused by the difference between “Yes, sir,” and “Aye aye, sir.” It was simple. Asked a question to vhich the answer was affirmative, you said “Yes, sir.” Given an order, you said “Aye aye, sir.” It didn’t take many trips to the first lieutenant’s barrel to get it right.

Captain Haag touched his screen. “But first, you have to get to Hope Nation.” My heart sank. “We’ll begin at the wreck of Celestina,Mr. Seafort. Proceed.” He tilted back in his armchair.

I picked up the caller. “Bridge to engine room, prepare to Defuse.” My voice squeaked, and I blushed.

“Prepare to Defuse, aye aye, sir.” Chief McAndrews’s crusty voice, from the engine room below. “Control passed to bridge.” Naturally, the console’s indicators from the engine room were simulations; Captain Haag wasn’t about to Defuse for a mere middy drill.

“Passed to bridge, aye aye.” I put my index finger to the top of the drive screen and traced a line from “Full” to “Off”. The simulscreens came alive with a blaze of lights, and I gasped though I’d known to expect it. Stars burned everywhere, in vastly greater numbers than could be imagined groundside.

“Confirm clear of encroachments, Lieutenant. Please,” I added. After the drill she’d still be my superior officer. Lieutenant Dagalow bent to her console.

Our first priority in emerging from Fusion was to make sure there were no planetary bodies or vessels about. The chance was one in billions, but not one we took lightly. Darla always ran a sensor check, but despite the triple redundancy built into each of her systems, we didn’t rely on her sensors.

Navigation was based on an overriding principle: don’t trust machinery. Everything was rechecked by hand.

“Clear of encroachments, Mr. Seafort.” Technically Ms.

Dagalow should have called me “sir” during the drill, while I acted as Captain, but I wasn’t about to remind her of that.

“Plot position, please, ma’am. I mean, Lieutenant.”

Lieutenant Dagalow set the puter to plot our position on her star charts. The screen filled with numbers as a cheerful feminine voice announced, “Position is plotted, Mr. Seafort.”

“Thank you, Darla.” The puter dimmed her screens slightly in response. I’m not going to get into the age-old question: was she really alive? That one caused more barroom fights than everything else put together. My personal opinion was–well, never mind, it doesn’t matter. Ship’s custom was to respond to the puter as a person. All the correct responses to polite phrases and banter were built into her. At Academy, they’d told us crewmen found it easier to relate to a puter with human mannerisms.

“Calculate the new coordinates, please,” I said. Lieutenant Dagalow leaned forward to comply.

Captain Haag intervened. “The Lieutenant is ill. You’ll have to plot them yourself.”

“Aye aye, sir.” It took twenty-five minutes, and by the time I was done I’d broken out in a sweat. I was fairly sure I was right, but fairly sure isn’t good enough when the Captain is watching from the next seat. I punched in the new Fusion coordinates for the short jump that would carry us to Hope Nation.

“Coordinates received and understood, Mr. Seafort.” Darla.

“Chief Engineer, Fuse, please.”

“Aye aye, sir. Fusion drive is... on.” The screens abruptly went blank as Darla simulated reentry into Fusion.

“Very well, Mr. Seafort,” the Captain said smoothly.

“How long did you estimate second Fusion?”

“Eighty-two days, sir.”

“Eighty-two days have passed.” He typed a sequence into his console. “Proceed.”

Again I brought the ship out of Fusion. After screening out the overpowering presence of the G-type Hope Nation sun, we could detect Orbit Station circling the planet. Lieutenant Dagalow confirmed that we were clear of encroachments.

Then she became ill again and, increasingly edgy, I had to plot manual approach myself.

“Auxiliary engine power, Chief.” My tone was a bark; my grip on the caller made my wrist ache.

“Aye aye, sir. Power up.” Mr. McAndrews must have been waiting for the signal. Of course he would be; Lord God knows how many midshipmen he’d put through nav drill over the years.

“Steer oh three five degrees, ahead two-thirds.”

“Two-thirds, aye aye, sir.” The console showed our engine power increasing. Nervously I reminded myself that Hiberniawas still cruising in Fusion, that all this was but a drill.

I glanced at the simulscreen. “Declination ten degrees.”

“Ten degrees, aye aye, sir.”I approached Orbit Station with caution. Easily visible in the screens, it grew steadily larger. I braked the ship for final approach.

“Steer oh four oh, Lieutenant.”

“Aye aye, sir.”

“Sir, Orbit Station reports locks ready and waiting.”

“Confirm ready and waiting, understood,” I repeated, trying to absorb the flood of information from our instruments.

Dagalow said, “Relative speed two hundred kilometers per hour, Mr. Seafort.”

“Two hundred, understood. Maneuvering jets, brake fifteen.” Propellant squirted from the jets to brake the ship’s forward motion.

“Relative speed one hundred fifteen kilometers, distance twenty-one kilometers.”

Still too fast. “Brake jets, eighteen.” We slowed further, but the braking threw off our approach. I adjusted by tapping the side maneuvering jets.

Our conventional engines burned LH2 and LOX as propellant ; water was cheap and Hibernia’sfusion engines provided ample energy to convert it, but there was a limit to how much we could carry. To go faster we would spend more water.

We’d spend an equal amount slowing down; nothing was free. Theoretically we could sail to Hope Nation on a few spoonfuls of LH 2 and LOX, but not in our lifetimes. How much time was worth how much loss of propellant? That depended on how much maneuvering lay ahead. A nice logistics problem with many variables.

Mine was not a smooth approach. I backed and filled, wasting precious propellant as I tried to align the ship to the two waiting airlocks. Captain Haag said nothing. Finally I was in position, our airlocks two hundred meters apart, our velocity zero relative to Orbit Station.

“Steer two seven oh, two spurts.” That would move our pencil to the left, still parallel with the nearby station. It did, far too fast. I had forgotten how little fuel is needed for a correction at close quarters. Hibernia’snose swung perilously close to the station’s waiting airlock.

I panicked. “Brake ninety, one spurt!”

Lieutenant Dagalow entered the command, her face impassive.

Lord God in heaven! I’d compounded my error by pulling away the tail of the ship, instead of the nose. “Brake two seven oh, all jets!”

The screen darkened as Orbit Station loomed into our shadow.

Alarm bells shrilled. The screen suddenly jerked askew.

My hand flew to the console to brace myself for a jolt that never came.

Darla’s shrill voice overrode the screaming alarms. “Loss of seal, forward cargo compartment!”

Ms. Dagalow shouted, “Shear damage amidships!”

The main screen lurched. Darla’s voice was urgent.

“EMERGENCY!The disk has struck! Decompression in Level 2!” I was sick with horror.

Captain Haag pushed his master switch. The alarms quieted to blessed silence. “You’ve killed half the passengers,” he said heavily. “Over a third of your crew is in the decompression zone and is most likely dead. Your ship is out of control.

The rupture in the hull is bigger than the forward airlock.”

I’d done more damage to my ship than even Celestinahad sustained. I closed my eyes, unable to speak.

“Stand, Mr. Seafort.”

I stumbled to my feet, managed to come to attention.

“You didn’t do all that badly until the docking,” the Captain said, not unkindly. “You were slow, but you got the ship into correct position. You failed to anticipate decisions, and so you had too much to do in a short time. As a result you lost your ship.”

“Yes, sir.” I’d lost my ship, all right. And with it any chance of making lieutenant before home port.

He surprised me. “Review the manual again, Seafort. As many times as it takes. By next drill I’ll expect you to have it right.”

“Aye aye, sir.”

“Dismissed.” I slunk out.

It was the worst day of my life.

“I don’t want to talk about it, Amanda.” She was perched on her bed in her ample cabin on Level 1, while I sat on the deck nearby.

I was off duty, and ship’s regs permitted officers to socialize with passengers. Sensibly enough, the Naval powers had decided to endorse what they could not prevent.

“Nicky, everyone makes mistakes. Don’t punish yourself, just do better next time.”

My tone was bitter. “Vax and Alexi dock the ship and come out alive. I’m the senior midshipman and I can’t.”

“You will,” she soothed. “Study and you will.”

I didn’t tell her how Lieutenant Cousins would have to coach me all over again to prepare for the drill. When he was done I’d be lucky if I could remember how to dress myself.

I writhed in disgust. I didn’t normally panic; I handled some problems reasonably well or I wouldn’t have made it through Academy. But knowing everyone’s life depended on me was too much. I knew I’d never be able to cope.

Morose, I settled into a chair. “I’m sorry I bothered you with this, Amanda.”

“Oh, Nicky, don’t be silly. We’re friends, aren’t we?”

Yes, but that’s all we were. I’d have liked to be more, but there were three long years between us and she didn’t seem interested. “Why do they torture midshipmen with those drills, anyway? That’s what the Pilot is for.”

“The Captain is in charge of the ship,” I said patiently.

“Always. Pilot Haynes, like the Chief Engineer and the Doctor, is staff, not a line officer.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“It means he’s not in the chain of command. If the Captain fell ill, the first lieutenant would command, then Ms. Dagalow, then Lieutenant Malstrom.”

“But you’d still have the Pilot to dock the ship. Everybody can’t be sick or gone.”

“But the Pilot wouldn’t be ultimately responsible. It’s not his ship.”

“Still, it’s silly to expect boys just out of cadet academy to know how to fly the ship.”

“Sail. Sail the ship.”

“What’s the difference? You know what I mean.”

I tried to explain. “Amanda, we’re here to learn what the lieutenants and the Captain do. That’s what the drills are for.”

“I still think it’s silly,” Amanda said stubbornly. “And cruel.” I let it be.

3

“Turn that thing down, Alexi.” I got myself ready for bed.

It had been a bad day all around and I was cross.

“Sorry, Mr. Seafort.” Quickly he lowered the volume of his holovid. Just a year younger than I, Alexi Tamarov was everything I wanted to be: slim, graceful, good-natured, and competent. But he was addicted to his slap music, while my own taste ran to classical composers: Lennon, Jackson, and Biederbeck.

I regretted my temper, but still, I thanked Lord God I was senior and had the right to order the music turned low. I’d have managed somehow even if I weren’t in charge, but life had enough trials without that. As senior, I had my choice of bunks and got first serving at morning and afternoon mess, and I supposedly controlled the wardroom, though I was aware my authority was precarious at best.

In a Naval vessel, midshipmen were thrown together with little forethought. Fresh from Academy or with years of service, we were expected to live and work together smoothly.

By ship’s regs it was the senior middy’s duty to run the wardroom, but tradition gave any middy the right to challenge him. In that case the two would fight it out. Because conflicts were inevitable and their resolution necessary, officers turned a blind eye to the scrapes, black eyes, or bruises a midshipman might develop from interacting with his fellows.

Vax Holser and I had an unspoken understanding; he bullied the other middies, and we left each other alone. We both knew that if I pulled rank on him I’d have to back it up. I ignored his calling me “Nicky” with barely concealed contempt; beyond that, we both avoided the test.

Vax stirred, opened one eye to glare at Alexi. I hoped he wouldn’t start anything, but he growled, “You’re an asshole.”

Alexi made no reply.

“Did you hear me?”

“I heard you.” Alexi knew he couldn’t tangle with Vax.

“Tell me you’re an asshole.” The trouble with Vax was that once he started he wouldn’t let up.

Alexi glanced at me. I was noncommittal.

“I don’t feel like getting up, Tamarov. Tell me.”

“I’m an asshole!” Alexi snapped off the holovid and threw

himself on his bed, facing the partition. His back was tight.

“I already knew that.” Vax sounded annoyed.

In the unpleasant silence I glumly recalled my arrival a few weeks before. Lugging my gear, I’d reported to Hiberniaat Earthport Station, the huge concourse orbiting above Lunapolis City. Preoccupied with loading the incoming stores, Lieutenant Cousins glanced at my sheaf of papers and sent me to find the wardroom on my own.

As I bent awkwardly to open the wardroom hatch a figure cannoned outward through the hatchway, propelling me across the corridor, duffel underfoot, papers flying. I fetched up against the far bulkhead in disarray. My shoulder felt broken.

“Wilsky, get your ass in here!” The bellow came from within.

The young middy froze in horror as I swiped helplessly at a cascade of papers. He darted forward and bent to help me pick up my documents. “You’re Wilsky?” was all I could think to say.

“Yes, uh, sir,” he said, glancing at my length of service pins, knowing instantly that I was his senior.

“Who’s that?” I beckoned to the closed hatch.

“That’s Mr. Holser, sir. He’s in charge. He was going–”

Wilsky grimaced as the hatch sprang open. A huge form loomed over us.

“What the devil do you think–” The muscular midshipman frowned down at me as I crouched in the corridor stuffing papers back into their folders. “Are you the new middy?”

“Yes.” I stood. Automatically I checked his length of service pins. When I got my orders I was told I’d be first middy, but mistakes happen.

“You can put your–” His face went white. “What the bloody hell!” With dismay, I realized that no one had told him. He’d thought he was going to be senior.

Remembering, I sighed. Our first month had not been easy, and I had seventeen more to endure before landfall. I couldn’t physically overpower Vax Holser. Unfortunately, I didn’t know how I could tolerate him either.

“It is precisely because of that, Mrs. Donhauser, because the distances are so great and the voyages so long, that authority is made so rigid and discipline so harsh.”

Mrs. Donhauser listened closely to Khali Ibn Saud, our amateur sociologist and, by profession, an interplanetary banker.

It was a quiet afternoon some two months into the voyage, and I was sitting in the Level 2 passengers’ lounge.

“I’d think distance would have the opposite effect,” she countered. “As people got farther from central government, bonds of authority would be loosened.”

“Yes!” His tone was excited, as if Mrs. Donhauser had proven his point. “They certainly would, if all were left alone. But central authority, our government, reacts, you see? To maintain control it provides rules and standards and insists we adhere to them regardless of circumstances. And our government is willing to invest time and effort in enforcing them.”

The lounge was decorated in pale green, said to be a calming color. From the look of Mr. Barstow, sound asleep in a recliner, the decor was effective. The size of two passenger staterooms, the lounge could seat at least fifteen passengers comfortably. It was furnished with upholstered chairs, recliners, a bench, two game tables, and an intelligent coffee/ softie dispenser.

I was only half interested in the debate. Mr. Ibn Saud’s

theory was not new. In fact, they had presented it better at Academy.

Mrs. Donhauser appealed to me. “Tell him, young man.

Isn’t it true that the Captain is his own authority here in midspace? That he answers to no one?”

“That’s two questions,” I answered. “Yes, and no. The Captain is the ultimate authority on a vessel under weigh. He answers to no one aboard ship. But his conduct is prescribed by the regs. If he deviates from them, on his return he will be removed, or worse.”

“So you see,” Ibn Saud said triumphantly, “central authority is maintained even in the depths of space.”

“Foo!” she threw at him. “The Captain can sail slower, faster, even take a detour if he wishes. Central government has nothing to say about it.”

He shrugged, looking at me as if to ask, “What’s the use?”

“Mrs. Donhauser,” I offered, “I think you make a mistake trying to contrast the Captain’s powers with United Nations authority. The Captain isn’t opposed to central authority. He IS that authority. Legally he can marry people, divorce them, even try and execute them. He has absolute and undiluted control of the vessel.” That last was a quote from an official commentary on the regs; I threw it in because it sounded good. “There was a ship. Cleopatra.Have you heard of it?”

“No. Should I?”

“It was about fifty years ago. The Captain, I don’t remember his name–”

“Jennings,” put in Ibn Saud, his head bobbing in anticipation of my point.

“Captain Jennings acted quite strangely. The officers conferred with the Doctor and relieved him of command on grounds of mental illness. They confined him to quarters and sailed the ship directly to Earthport Station.” I paused for effect.

“So?”

“They were hanged, every one of them. A court-martial found them mistaken in believing the Captain unfit for command. Even though they acted in good faith, they were all hanged.” A silence grew. “You see, the government is absolutely determined to maintain authority, even in space,” I said. “The Captain is the representative of the government, as well as the Church, and he must not be overturned.”

“It’s a bizarre case!”

“It could happen today, Mrs. Donhauser.”

“And besides, that must have been a Naval vessel,” she said. “Not a passenger ship.”

That was too much for me. You’d think people would know what they were getting themselves into. “Ma’am, you may be confused because Hiberniahas a Naval crew, carries a full complement of civilian passengers, and has a hold full of private cargo. What counts is that the Captain and every member of the crew are Naval officers and seamen. Hiberniais a commissioned Naval vessel. By law the Navy carries all cargo bound for the colonies, but legally that cargo is no more than ballast. And the passengers, technically, are just extra cargo. You have no rights aboard this ship and no say whatsoever in what happens on board.” I spoke courteously, of course. A midshipman overheard insulting a passenger was not likely to do so again.

“Oh, really?” She was unfazed. I decided she would make a formidable missionary. “Well, it just so happens we vote on our menus, we have committees to run social functions, we elect the Passengers’ Council, we even voted on whether to stop at the Celestinawreck next week. So where’s your dictatorship now?”

“Window dressing,” I said. “Look. You have to be a VIP to afford an interstellar voyage, right? The Navy doesn’t go out of its way to alienate important people. All of us, officers and crew, are required to be polite to passengers and to assent to your wishes wherever possible. Because you’re valuable you get the best accommodations, the best food, our best service. But that changes nothing. The Captain can override any of your votes anytime he has a mind to.” I wondered if I’d gone too far.

The feisty old battle-ax put me at ease. “You argue well, young man. I’ll think it over. Next time I see you I’ll tell you why you’re wrong.”

I grinned. “I look forward to the lesson, ma’am.”

I stretched, excused myself, and went back to Level 1 and the wardroom. Whatever arguments Mrs. Donhauser marshaled wouldn’t change a thing. The U.N, knew our world had had enough of anarchy. Central control was not imposed by the government on an unwilling populace. Rather, it was appreciated and respected by the vast mass of citizens. Brushfire wars and chaotic revolutions had finally ceased; our resulting prosperity had powered our explosion into space and the colonization of planets such as Hope Nation and Detour.

The Navy, the senior U.N. military service, was the U.N.’s bulwark against the forces of diffusion inherent in a colonial system.

I stripped off my uniform and crawled into my bunk, trying not to wake Alexi. Lieutenant Cousins had set him over the barrel yesterday. Now Alexi had to eat standing, and he wasn’t sleeping well. One learned to live with canings, but I knew Alexi too well to believe he’d been insolent and insubordinate as the lieutenant had alleged. Cousins was having a bad day, or was looking for an excuse to assert his authority.

According to regs any middy could be caned, but tradition held there was a dividing line. Alexi, at sixteen, should have been over the line except for a grievous offense. By statute Lieutenant Cousins was within his rights, but not by custom.

Alexi was miserable but hadn’t complained, which was right and proper.

I slept.

4

Two weeks later they gave me another docking drill. It took me forever to plot our course. I labored an hour just to calculate our position, until even the Captain was fidgeting with annoyance. By the time I came off the bridge I was wringing wet, but I hadn’t wrecked the ship, though I’d bumped the airlocks together fairly hard.

I went looking for Amanda to tell her of my accomplishment. I found her in the passengers’ lounge watching a holovid epic. She turned it off and listened instead to my excited replay of my maneuvers.

Though I no longer sat at her table in the dining hall, Amanda and were becoming good friends. We took long walks together around the circumference corridor. We read together in her cabin. She told me about her father’s textile concern, and I told her stories of Academy days. Our only physical contact was to hold hands. I could have slept with her; it wasn’t against regs, and I lined up with the other middies for my sterility shot from Doc Uburu every month.

But she didn’t invite me and I couldn’t push, not with a passenger.

A few days after my success on the bridge I relaxed on my bunk, watching Sandy tease Ricky Fuentes, our ship’s boy.

“C’n I try it? Please, sir? Please?” The ship’s boy reached for the orchestron Sandy held over his head, grinning. We all liked Ricky, a happy twelve-year-old. Even Vax was congenial to him. The youngster’s trusting good nature encouraged it.The ship’s boy roamed crew quarters, officers’ country, and passenger lounges with impunity. It was all part of his job as ship’s gofer. Ricky took messages, retrieved gear that crewmen or officers forgot, generally made himself useful.

Every capital ship had a ship’s boy, usually an orphan of a career sailor. Traditionally, he graduated to seaman first class and usually made petty officer before he was twenty.

Sandy gave him his orchestron. The boy selected harpsichord, French horn, and tuba, set down a bongo beat, and tapped out a simple melody on the tiny keyboard. He set it

to repeat. Then he set up a counterpoint, using different instruments.

Ricky listened to the orchestron develop the theme he had created. “Zarky! Real zarky!” I think that meant he liked it.

I was only five years older than he, but joespeak changes fast.

The machine burbled to a stop. “Thanks, Sandy, I gotta run.

I’m helping in the kitchen tonight. I mean the galley. Bye, sir!” He ran off.

At Ricky’s age, I was chopping wood for Father. I wasn’t outgoing and sociable, as he was. I never would be. At home Father and I didn’t talk often, and we certainly didn’t laugh.

Sandy left, and I dozed.

Sometime later Vax came and slapped the light on, waking me from a pleasant dream.

I muttered, “Turn it off, will you?”

He ignored me, undressing slowly.

“Vax, turn off the bloody light!”

“Sure, Nicky.” He slapped it off, managing to express contempt with the gesture.

Perhaps it was the heavy dinner, or the lack of exercise.

Drugged and lethargic, I fell instantly back to sleep.

Sometime later I was aware of a complaining voice. “It’s cold. Turn the heat up, Wilsky.” I heard the rustle of sheets as Sandy dragged himself out of bed to dial up the heat.

A few minutes later Vax started again. “Sandy, it’s too hot. Turn it down.” Once again the boy got up and turned off the heat. This time it took me longer to get back to my dream.

“Turn the heat up, Wilsky!”

I snapped awake, inwardly raging. Alexi groaned. Sandy, who must have been asleep, did not answer.

“Wilsky, you damned asshole, get up and give us some heat!” Now Vax was adding blasphemy to his boorishness.

I heard the rustle of sheets as Sandy climbed out of his bunk and adjusted the temperature.

I lay awake, debating. I wouldn’t protect Sandy from all Vax’s hazing, but there came a point when Sandy had enough.

More would cause him emotional problems. For that matter, more would cause ME emotional problems. Where should I draw the line? And how could I do it without getting my head knocked off by the muscular gorilla in the next bunk, and permanently losing control of the wardroom? “Now turn it down.”

“It’s fine in here,” I heard myself say.

“It’s hot. That jerkoff doesn’t know how to adjust it properly.”

“Get up and do it yourself, Vax.”

He ignored me. “Wilsky, put your pretty little ass on the deck and fix the heat!”

I’d had enough. “Stay put, Sandy. That’s an order.”

“Aye aye, Mr. Seafort.” His tone was grateful.

“What in hell are you pulling, Nicky?”

I tried to sound authoritative. “Enough, Vax.”

“The hell you say!” So much for my sounding authoritative.

“Vax, turn the light on.” I waited, but he did nothing, forcing the issue. From the silent breathing I knew we were all awake. “Alexi, get up. Turn on the light.”

“Aye aye, Mr. Seafort.” Alexi slapped the light switch, his eyes bleary, hair tousled. Quickly he sank back into bed, out of harm’s way. Vax sat up, glaring.