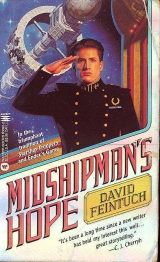

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

“Vax, will you stay with me?”

Vax Holser, his pent-up emotions roiling, glared at me with such fury as I have never seen from another man. He twice opened his mouth to speak. Then he stalked out in a passion, slamming the hatch shut.

I stayed in the infirmary during evening mess, in the chair the Chief had vacated. The Captain’s breathing varied, sometimes regular and deep, sometimes ragged. Late in the evening Dr. Uburu slipped an oxygen mask over his nose and mouth. She introduced vapormeds into the oxygen mixture; I couldn’t tell if they helped. She sent the med tech to the galley for a tray for me. I ate in my chair, never taking my eyes from the still form in the bunk.

“I’ll watch him, Nicky,” she said after I began to doze.

“Go to bed.”

“Let me stay.” It was somewhere between a demand and a plea. Perhaps she understood from my eyes. She nodded.

She checked the alarms on the bedside monitors and retired to the anteroom. I dozed, came awake, and dozed again. The bright lights accented the stillness. Finally I curled up in the chair and slept.

I woke toward morning, to realize the labored sounds of his breathing had stopped. I called Dr. Uburu; she came and stood next to me by his still form under the clean white sheet.

“The alarms. Why didn’t they... “

“I turned them off.” She answered my look of betrayal.

“I could do nothing more for him. Except let him go in peace.”

Stunned, I sank back into the chair. I don’t know how long I sat there alone; I got up mechanically when I heard the change of watch after breakfast. I went out into the anteroom where Dr. Uburu waited.

She got to her feet. “I’m going to meet with the Chief and Pilot Haynes.” I didn’t answer.

I left the infirmary, followed the corridor to the wardroom, passing someone on the way. Sandy and Alexi were inside; Alexi, just off watch, was in his bed. Sandy stood as I entered.

“Out, both of you.” They scrambled to the hatch. I pulled off my jacket and lay on my bunk. My head spun, but sleep evaded me. I heard noises in the corridor. I tried to block them out, could not. I lay awake in a stupor.

Hours later Alexi knocked on the hatch. “Mr. Seafort–”

“Stay out until I give you permission to enter!”

“Aye aye, sir.” The hatch shut.

I buried my head in the pillow, hoping for tears. None came.

I awoke later in the day with an intense thirst. I got up, found my jacket, went to the head. As I slopped water from my hand to my mouth I studied my reflection in the mirror.

My hair was wild; there were hollows under my eyes. My expression was frightening.

I splashed cold water on my face and went back to the wardroom. I dressed in clean clothes and combed my hair.

Then I went below to the ship’s library on Level 2, where I signed out the holovid chips for the Naval Regulations and Code of Conduct, Revision of 2087. I took them back to the wardroom and sat on my bunk.

It took about twenty minutes to find what I was looking for.

“Section 121.2. The Captain of a vessel may relieve himself of command when disabled and unfit for duty by reason of mental illness or physical sickness or injury. Upon his certification of such action in the Log, his rank of Captain shall be suspended and command shall devolve on the nextranking line officer.”

I thumbed through the regs looking for other half-remembered sections. I flipped back and forth, carefully reading definitions and terms.

The hatch opened cautiously. Vax looked in, then entered.

We faced each other.

“He died before he signed it.” It was half statement, half question.

“Yes,” I said.

“What will you do?”

“I don’t know.” I saw no reason to hide it.

“Nicky–Mr. Seafort–”

“You can call me Nicky.”

“–you can’t captain the ship.”

I was silent.

“You can’t maneuver her. You can’t plot a course. You don’t understand the drives.”

“I know.”

“Step aside, Nicky. It’s just until we get back home.

They’ll send us out with new officers.”

“I’ve been thinking about doing that,” I said.

“For the ship’s safety. Please.”

“You’d run her?”

“Me, or the officers’ committee. Doc and the Chief and the Pilot. It doesn’t matter. They’re meeting right now, to figure what to do.”

“I understand.” I flipped off the holovid.

“You agree?”

“No. I understand.” I got up. “Vax, I wanted you to command. I begged him to sign your commission the first night he was ill.”

“I know. After how I treated you I can hardly look you in the eye.” He hesitated. “It’s just a fluke I wasn’t senior,”

he said bitterly. “Four months difference.”

“Yes.” I put the holovid in my pocket and went to the hatch. “I wish I’d gone with Captain Haag on the launch, Vax. If I could choose now, that’s where I’d be.”

“Don’t talk like that, Nick.”

“I’m desperate.” I went out.

No one but the med tech was at the infirmary. The Captain’s body was already in a cold locker. I tried the Doctor’s cabin, but no one answered. I went below along the circumference passage to the Chiefs quarters, and met the Pilot just coming out the hatch.

“I was on my way to get you.” He gestured me inside.

The Chiefs cabin was the same size as the one in which Lieutenant Malstrom and I had played chess. Dr. Uburu and the Chief were seated around a small table. I found a chair and joined them.

“Nick.” The Doctor’s tone was gentle. “Someone has to decide what to do.”

“That’s right,” I said.

“The crew needs to know who’s in charge. We have to get the ship back home. We have to reassure the passengers.

The Passengers’ Council voted unanimously to return to Earthport, and wants the officers’ committee to take control.”

Chief McAndrews hesitated, glanced at the others.

“There’s ambiguity in the regs as to whether a midshipman can assume the Captaincy. We think he can’t. And even if he can, we want you to remove yourself. And if you don’t, we’ll remove you for disability.”

“Good,” I said. “Get me out of this, please. Let’s start with your first point. What regs are you looking at?” They all relaxed visibly at my response.

The Chief glanced at his notes. “ ‘Section 357.4. Every watch not commanded by the Captain shall be commanded by a commissioned officer under his direction.’ “ He cleared his throat. “A midshipman is not a commissioned officer.

357.4 says you have to be commissioned to command a watch.”

“As a midshipman I can’t command a watch. I agree with you.”

“Then it’s settled.” Dr. Uburu.

“No. I’m no longer a midshipman.”

“Why not?”

I reached for a holovid and inserted my chip. “ ‘Section 232.8. In case of death or disability of the Captain, his duties, authority, and title shall devolve on the next-ranking line officer.’ “

“So?”

“ ‘Section 98.3. The following persons are not line officers within the meaning of these regulations: a Ship’s Doctor, a chaplain, a Pilot, and an Engineer. All other officers are line officers within the meaning of these regulations.’ “

“ ‘Section 101.9,’ “ countered the Chief. “ ‘The Captain of a vessel may from time to time appoint a midshipman, who shall serve in such capacity as the Captain and his officers may from time to time direct.’ 101.9 suggests a middy may not even be an officer.”

I scrolled my holovid to Section 92.5. “ ‘Command of any work detail may be delegated by the Captain or the officer of the watch to any lieutenant, midshipman, or other officer in his command.’ “ I looked around the table, repeating the deadly phrase. “Lieutenant, midshipman, or other officer.”

I said into the silence, “A midshipman is mentioned as an officer. A line officer.”

The Pilot stirred. “It’s still ambiguous. A midshipman isn’t commissioned. The regs don’t say a middy can become Captain.”

“Nobody thought of it happening. I agree.” I flipped back to the definitions section. “ ‘12. Officer. An officer is a

person commissioned or appointed by authority of the Government of the United Nations to its Naval Service, authorized thereby to direct all persons of subordinate rank in the commission of their duties.’ “

I raised my eyes. “An officer doesn’t have to be commissioned. Look, I want to reach the same conclusion you do.

But the regs are clear. They don’t say the Captaincy shall devolve on the next commissioned officer. They say line officer. I’m an officer. I’m not one of the officers excluded from line of command. I’m the senior line officer aboard.”

“It’s still not explicit,” said the Chief. “We have to guess how to interpret the various passages put together. We can conclude a midshipman never succeeds to command.”

“There’s two problems in doing that. One, when we get home you’d be hanged.”

There was a long silence. “And the other problem?” Dr.

Uburu finally asked.

“I will construe it as mutiny.”

They exchanged glances. I realized the possibility had occurred to them before I arrived.

“It hasn’t come to that,” the Chief said. “Let’s say we all conclude that you’re next in line. Step down. You’re not ready to command.”

“I’ll be glad to. Just show me where it’s allowed.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” said Dr. Uburu. “Quit. Resign the Captaincy. Relieve yourself.”

“On what grounds?”

“Incompetence.”

“Do you mean my lack of skill and other qualifications, or are you suggesting I’m mentally ill?”

“Nobody’s saying you’re mentally ill,” she protested.

“ ‘Section 121.2. The Captain of a vessel may relieve himself of command when disabled and unfit for duty by reason of mental illness or physical sickness or injury.’ “ I laid down my holovid. “I am not physically sick or injured.

I don’t believe I’m mentally ill any more than you do.”

“Isn’t it an inherent authority?” she asked. “The Captain can relieve others. Surely he has inherent authority to relieve himself.”

I said, “I thought of that. So I looked it up. ‘Section 204.1.

The Captain of a vessel shall assume and exert authority and control of the government of the vessel until relieved by order of superior authority, until his death, or until certification of his disability as otherwise provided herein.’ I don’t think they wanted Captains going around relieving themselves from duty.”

“This is ridiculous,” said the Pilot. “Everyone agrees, even you, that you shouldn’t be Captain. Yet you’re telling us we’re stuck with you, that you can’t quit, even though it’s best for the ship.”

“There’s a reason for that,” I told him. “You all know the Captain isn’t a mere officer. He’s the United Nations Government in transit. The Government cannot abdicate.”

“Do it anyway, Nicky,” Dr. Uburu said gently. “Just do it.”

“No.” I looked at each of them. “It is dereliction of duty.

I swore an oath. ‘I shall uphold the Charter of the United Nations, and the laws and regulations promulgated thereunder, to the best of my ability, by the Grace of Lord God Almighty.’ I no longer have a choice.”

“You’re seventeen years old,” said Chief McAndrews.

“There are a hundred and ninety-nine people aboard whose lives depend on the safe operation of this vessel. We have to relieve you.”

“You may relieve me only on the same grounds I can relieve myself,” I said. “Look it up. I will consent to being relieved when a legal basis exists. Otherwise, I must resist.”

The Chief thumbed through the holovid to the section on disability. After a few moments, he reluctantly pushed it aside.

We had reached an impasse. We sat around the little table, hoping a solution would occur.

“And Vax?” the Doctor asked.

“Vax is better qualified. But Vax is not Captain. He’s a midshipman. I am senior to him.”

“Even though he is far better able to handle the ship,” she said.

“Even though. You know how I tried to get the Captain to sign his commission.” I closed my eyes. I was desperately tired. “There is one solution.” She looked up at me, waiting.

“Sign the Log, witnessing that Captain Malstrom commissioned Vax lieutenant before he died. I will acquiesce.”

All eyes turned to the Ship’s Doctor. She studied the tabletop for a long time. The tension in the room was palpable.

After several minutes she raised her eyes and said, “I will not sign the Log in witness. Captain Malstrom did not grant Vax Holser a commission before he died.” The Pilot let his breath out all at once.

She went on, “I realize now we are here in error. The Captain had ample opportunity, not just on his sickbed, but during the weeks after he took command, to commission Vax.

He chose not to, knowing Mr. Seafort was senior midshipman. I know, just as you all know, that Captain Malstrom would acknowledge Mr. Seafort is next in line of command.

Captain Malstrom had authority to leave Nick as senior remaining officer and did. We had no say in the matter while he lived. We have no say in the matter now.”

I had one more hope. “Chief, you were in the infirmary with Captain Malstrom. If you can say you heard him commission Vax... “

The Chief didn’t hesitate, not for a second. “The day I sign a lie into the Log, Mr. Seafort, is the day I walk unsuited out the airlock. No. I heard no such thing.” He fingered the holovid. “We are all sworn officers. We all uphold the Government. It appears that the Government, in its unfathomable wisdom, has put you in charge. You know I wish it were not so. But my wishes don’t count. Sir, I am a loyal officer and you may count on my service.”

I swallowed. “I wanted you to argue me out of it, not the other way around. For the moment, I am Captain-designate.

I will be Captain when I declare I have taken command of the ship, as did Captain Malstrom. First, I’m going back to my bunk to try to find a way out of this. Let’s leave everything as it is. We’ll meet at evening mess.” I stood to go.

Automatically, all three of them stood with me.

9 Vax and Alexi snapped to attention when I crossed the wardroom threshold. They, at least, no longer considered me just the senior middy.

“I don’t have command yet,” I told them. “This is still my bunk and I want to be alone. Go pester the passengers or polish the fusion drive shaft. Beat it.”

Alexi grinned with relief at my sally; he was as unsettled as the rest of us. He and Vax hurried out.

I lay on my bunk fiddling with my holovid until eventually I tossed it aside in disgust. I was trapped. I grieved for my friend Harv, but I was furious he hadn’t had sense enough to commission Vax the day he took command. Vax could pilot, could navigate, understood the fusion drives, and had the forceful personality of a Captain.

I must have dozed. As afternoon watch ended I woke, ravenous. I couldn’t remember when I’d last eaten. I washed and hurried to the dining hall for the evening meal. Masterat-arms Vishinsky and four of his seamen stood outside the hatch, with their billies. He saluted.

“What’s this about?” I gestured to his sailors.

“Chief McAndrews ordered us up as a precaution, sir.

There was some kind of demand from the passengers and an, uh, inquiry from the crew.”

I spotted the Chief at his usual table. He stood when I approached. I flicked a thumb toward the master-at-arms and raised an eyebrow. “A written demand was delivered to the bridge, sir.” His voice was quiet. “By that Vincente woman.

Signed by almost all the passengers.”

“What do they want?”

“To go home. That part’s easy; we can Fuse any time.

They demand that responsible and competent officers control the ship, forthwith. Commissioned officers who have reached their majority.”

“Ah.”

“Yes, sir.” He paused. “And inquiries have come up from the crew,” he said with delicacy. “Wondering where authority now rests.”

“Oh, brother.”

“Yes. The sooner you declare you’ve taken command, the better.”

“Very well. After dinner. The officers will join me on the bridge.”

“Aye aye, sir.” He looked around the rapidly filling hall.

“The evening prayer, sir. Will you give it?”

“And sit at the Captain’s table, in the Captain’s place?” I was repelled by the thought.

“That’s where the Captain usually sits.” His tone had a touch of acid.

“Not tonight. I’ll say the prayer as senior officer, but from my usual place.”

I went to my accustomed seat. Several passengers sharing my table looked upon me with hostility. None spoke. I decided I could ignore it.

When the hall had filled I stood, and tapped my glass for quiet. “I am senior officer present,” I stated. Then, for the first time, I gave the Ship’s Prayer I had heard so often. “Lord God, today is March 12, 2195, on the U.N.S. Hibernia.We ask you to bless us, to bless our voyage, and to bring health and well-being to all aboard.” I sat, my heart pounding.

“Amen,” said Chief Engineer Me Andrews into the silence. A few passengers murmured it after him.

I wouldn’t call dinner a cheerful affair; hardly anyone acknowledged my presence. But I was so hungry I hardly cared.

I avidly consumed salad, meat, bread, then coffee and dessert.

The passengers at my table watched in amazement. I suppose they had reason; the day after the Captain’s death his successor sat at a midshipman’s place, eagerly devouring everything but the silverware.

After the meal I went back to the wardroom. I took out fresh clothes, showered thoroughly, dressed with extra care.

I even shaved, though it wasn’t really necessary.

Reluctantly, I went to the bridge. Sandy, who had been holding nominal watch alone–the ship was not under power–leaped to attention on my arrival.

“Carry on.” My tone was gruff, to cover my uncertainty.

Then, “Mr. Wilsky, summon all officers.”

“Aye aye, sir.” The young midshipman keyed the ship’s caller. “Now hear this.” His voice cracked; he blushed. “All officers report to the bridge.”

Awash with physical energy I paced the bridge, examining the instruments, seeing none of them. Doc Uburu arrived, requested permission to enter. The Pilot followed shortly. A few moments later the Chief appeared. The middies were last; Vax and Alexi came hurrying–clean uniforms, hair freshly combed, like my own–and I smiled despite myself. We all stood, as if grouped for a formal portrait.

I picked up the caller, took a deep breath. I exhaled, and took another. “Ladies and gentlemen, by the Grace of God, Captain Harvey Malstrom, commanding officer of U.N.S. Hibernia,is dead of illness. I, Midshipman Nicholas Ewing Seafort, senior officer aboard, do hereby take command of this ship.”

It was done.

“Congratulations, Captain!” Alexi was first, then they all crowded around me with reassurance and support, even the Chief and the Pilot. It was not a jolly occasion; the death of Captain Malstrom precluded that. What they offered was more condolence than celebration.

After a moment I went to sit. I stopped myself: I had headed for the first officer’s chair. Trying to look casual, I sat in the Captain’s seat on the left. No laser bolt struck me.

I addressed my officers.

“Pilot, we’ll need new watch rotations. Take care of it, please. The middies will have to stand watch alone now; it can’t be helped. Dr. Uburu, attend to passenger morale before the situation worsens. Chief, I need your attention on the crew. If there’s serious discontent, you’re to know about it.

Pass the word that we have matters under control. Vax, you’ll help me get settled. Get a work party to move my gear to the Captain’s cabin. Sew bars on my uniforms. Reprogram Darla to recognize me as Captain.”

When I stopped they chorused, “Aye aye, sir.” It was a heady feeling. No arguments, no objections. I began to appreciate ship’s discipline.

“Anything else, anyone?”

“We can make Earthport Station in two jumps.” The Pilot.

“I’ll run the calculations tonight.”

The Chief said, “Don’t worry about the crew; they’ll settle down as soon as I remind them they get early shore leave.

They’ll be so happy to head for Lunapolis they won’t even think about who’s Captain.”

Alexi asked, “When do we Fuse for home, sir?”

I said, “I never told you we were going home.”

The shock of silence. Then a babble of voices.

I snapped, “Be quiet!” There was instant compliance. It didn’t surprise me; I wouldn’t have dared breathe had Captain Malstrom given such an order, friend or no friend. “Chief, do you have something to say?”

“With the Captain’s permission, yes, sir.” He waited for my nod. “Surely you can’t mean to go on. We’ve lost our four most experienced officers. The crew is frightened. I can’t answer for their behavior if we head for Hope Nation. The ship’s launch is gone; six passengers are dead. Sir, we never thought... Please. The only sensible thing is to go back.”

“Pilot?”

“I can get us back in two jumps, Captain. Six months. It’s eleven months to Hope Nation.”

“I already knew that. Anything else?”

“Yes, sir. The danger is obvious. It’s irresponsible of you to sail on.”

I didn’t hesitate. “Pilot, you’re placed on report for insolence. I will enter a reprimand in the Log. You are reduced two grades in pay and confined to quarters for one week, except when on watch.”

Pilot Haynes, his face red with rage, grated, “Understood, sir.” His fists were clenched at his side.

“Who else?” Of course, after that no one cared to speak.

“I’ll take your suggestions under advisement. In the morn-

ing I’ll let you know. You’re all dismissed. Mr. Holser, you will remain.”

After the bridge hatch shut behind the last of them I turned to Vax, who waited in the “at ease” position. I wasn’t looking forward to our interview. “You’re senior middy now, Vax.”

“Yes, sir.” He looked straight ahead.

“You recall the unpleasantness we had last month?”

“Yes, sir.”

“It’s nothing compared to the unpleasantness I’m going to make now, Mr. Holser.” Vax had settled in well as second midshipman, but now I had to leave the wardroom, and given his temperament he’d have the other middies climbing the bulkheads in a week. That is, if I didn’t put the brakes on.

My voice was savage. “You will do hard calisthenics–I repeat, HARD calisthenics, for two hours every day until further notice. You will report to the watch officer in a fresh uniform for personal inspection every four hours, day and night.” He looked stricken. “You will submit a five-thousand-word report on the duties of the senior midshipman under Naval regulations and by ship’s custom. Acknowledge!”

“Orders received and understood, sir!” His expression bordered on panic.

I stood nose to nose with him, my voice growing louder.

“You may think that in the privacy of the wardroom you can revert to your old bullying ways, and I won’t know because the other middies won’t tell me. They don’t have to tell me, Mr. Holser. I was a middy yesterday. I know what to look for!” I waited for a response.

“Yes, sir!”

I shouted, “Mr. Holser, if you exercise brutality in the wardroom, I’ll cut your balls off! Do I make myself clear?”

“Aye aye, sir!” A sheen of sweat appeared on his forehead. I knew he didn’t take the last threat literally, but we’d both served aboard ship long enough to know the Captain’s enmity was the worst disaster that could befall a crewman. I was giving him a reminder of that.

“Very well. Dismissed. See that I have bars on my uniforms by morning.”

“Aye aye, sir!” He practically ran from the bridge. I made a mental note to ease up in a few days. The exercise wouldn’t harm him–Vax liked working out–but reporting for inspection every four hours grew brutal, as one’s sleep deficit accumulated. Once, in Academy, Sergeant Trammel had made me... I sighed, thrusting away the memory.

I roamed the bridge, unnerved by the grim silence. Never before had I stood watch entirely alone, and certainly not when I had no superior to call in case of emergency. I toyed with the sensors, examined the silent simulscreen, stared at pinpoints of starlight until my eyes ached. My legs were weary, but I was reluctant to sit just yet.

I examined the bridge safe, found it unlocked. The Captain’s laser pistol was within, as well as the keys to the munitions locker. As a precaution, I changed the combination.

Returning at last to my chair, I turned on the Log and thumbed it idly, back to the start of our voyage. I screened the orders from Admiralty, entered by Captain Haag ages ago. “You shall, with due regard for the safety of the ship, proceed on a course from Earthport Station to Ganymede Station... You shall sail in an expeditious manner by means of Fusion to Miningcamp, from there to Hope Nation, and thence to Detour... you shall take on such cargo as the Government there may... revictualing and refueling as you may find necessary...”I keyed off the Log.

Idly I thumbed through our cargo manifest. Machinery for the manufacture of medicines, tools and dies, freeze-stored vegetable seeds, catalogs and samples of the latest fashions from Earth, bottled air for Miningcamp... I closed my eyes, rocking gently in the Captain’s chair, its soft upholstery inviting.

“Permission to enter bridge, sir.” I woke abruptly. Alexi waited respectfully in the corridor. Had he seen? Lord God, I hoped not; sleeping on watch was a cardinal sin.

“Come in.” I got him settled. He’d have little to do other than watch the quiescent instruments, but like me, Alexi had never served a watch alone and was eager to begin. I myself was already glad to escape the tedium.

I headed east along the circumference corridor to the Captain’s cabin. No one was posted outside; Captain Haag had dispensed with the marine guard the first week of the voyage.

I quelled an urge to knock respectfully, and went in.

The cabin was breathtaking. It was over four times as large as our wardroom, at least eight meters by five. It held only one bunk, which made it seem even more grand. So much space, for only one person. And I was the person! Subtle dividers made areas of the cabin seem like separate rooms. In one corner*Was a hatch; I tried it. A head; the Captain actually had his own head and shower. I was stunned.

I felt guilty even thinking of living in such luxury, while midshipmen constantly rubbed shoulders in their tiny quarters.

My gear, what little there was of it, was already laid out in a dresser built into the bulkhead. Vax had been busy: my uniforms, new patches freshly sewn on the shoulders, were hung neatly in a closet area in the corner. A ship’s caller sat on the table by the bunk. Across from the bed were easy chairs, a desk chair, even a small conference table. Or dining table. I wasn’t sure which.

I sat uneasily, feeling an intruder though Captain Malstrom’s gear was nowhere to be seen. Captain Haag’s must long since be gone to storage. I wondered gloomily how soon my own would follow. My eyes roved the bulkheads.

Pictures; someone had made an effort to decorate. A safe was built into the bulkhead. It was locked. I made a note to find the combination.

I undressed and got into bed; the mattress was amazingly soft. I switched off the light. The room was very still. I twisted from one position to another, unable to sleep despite my exhaustion. My thoughts turned to what I had accomplished. In the course of my first day, I’d managed to alienate everyone whose goodwill I needed. The Chief. The Pilot.

The senior middy. A bad start, but I couldn’t figure out what I could have done better.

As I tossed restlessly in the soft bunk I realized what was troubling me. It was too quiet. I was lonely.

10

In the morning I felt ill at ease using the head alone, so accustomed had I become to the wardroom’s lack of privacy.

I was a bit apprehensive when a knock came on the hatch; custom approaching the force of law forbade anyone to disturb the Captain in his cabin. In an emergency, or if he’d left standing orders to be notified, the Captain was summoned by ship’s caller; if there was no emergency, he was not bothered.

All the crew knew that, and passengers were not allowed in the section of Level 1 that contained the bridge and the Captain’s quarters.

Cautiously, I opened the hatch. Ricardo Fuentes, the ship’s boy, waited in the corridor with a cloth-covered tray. He stepped around me to set it on my dining table. Then his shoulders came up and he stood rigidly at attention, arms stiffly at his sides, stomach sucked in tight.

I was grateful for the familiar face. “Hi, Ricky.”

“Good morning, Captain, sir!” His voice was high-pitched and shrill.

I peered beneath the cloth. Coffee, scrambled eggs, toast, juice. It appeared his visit was a regular morning routine.

“Thanks.”

Twelve-year-old Ricky stood stiff. “You’re welcome, sir!” Clearly, he wasn’t about to unbend.

“Dismissed, sailor.”

“Aye aye, sir!” The boy about-faced and marched out. I sighed. Had I begun to resemble an ogre? Did it come with the job? Pilot Haynes and Vax Holser were on the forenoon watch list. As I reached the bridge I opened my mouth to ask permission to enter. Old habits die hard. Feeling foolish, I walked in. Vax jumped to attention; the Pilot did so more slowly.

“Carry on.” They eased back in their chairs as I crossed to my new seat. Vax’s uniform, I noticed, was crisply ironed.

I glanced at the console. The readouts seemed in order; I knew Vax or the Pilot would tell me if they weren’t.

“Chief Engineer, report to the bridge.” I put down the caller. When Chief Me Andrews arrived I said, “Chief, Pilot, I’ve decided we will continue to Miningcamp and Hope Nation.” The Chief pursed his lips but said nothing.

“I don’t have to give you reasons, but I will. Simply: going on involves Fusing and docking maneuvers; so does going home. The risks are equal.

“Now, once we’re at Hope Nation we know the Admiral Commanding will assign us a new Captain and lieutenants. It will mean sailing eleven months with inexperienced officers, instead of the six it would take to go home, but Hiberniacarries too many supplies that our colonies need, to abandon our trip lightly. Their supply ships arrive only twice a year.”

The Chief said only, “Aye aye, sir.” The Pilot was silent.

“Gentlemen, we’ll bury Captain Malstrom this forenoon, and we’ll Fuse this afternoon after the burial service.”

The bridge and engine room were unmanned and sealed.

We gathered around the forward airlock, seven deep in the crowded corridor. All the remaining officers, resplendent in dress uniform with black mourning sash across the shoulder, nearly all the crew, dressed as if for inspection. Lieutenant Malstrom had been as popular among the enlisted men as among the middies.

The rest of the corridor was filled with passengers: Yorinda Vincente, representing the Passengers’ Council, in the front row; behind her, Mr. Barstow, Amanda Frowel, the Treadwell twins, many others I knew, all waiting for the service to begin. Derek Carr, whose father had been lost earlier with the launch, his finely chiseled, aquiline face marred by sunken eyes and an expression of grief remembered. He nodded, but said nothing.