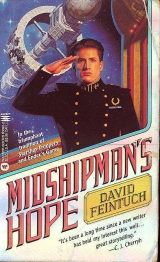

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

I lay back in my bunk, arm behind my head. “Vax, please give me twenty push-ups.” I was in big trouble.

“Prong yourself, Nicky.”

I heard Alexi’s sharp intake of breath.

“Vax, twenty push-ups. That’s an order.”

“Don’t be more of an ass than you can help.” Vax’s challenge was now in the open. Give me orders? Enforce them–if you can. He had the right, according to custom.

But a first middy wasn’t entirely without resources.

“This is a direct order, Vax. Twenty push-ups, on the deck.”

“No. You’re not man enough to give orders. Not inside the wardroom.” A wise distinction. His challenge was to my authority in the wardroom, not to ship’s authority in general.

“Mr. Holser, put yourself on report at once.” That meant, go knock on the first lieutenant’s hatch and tell him I had written you up for insubordination. It would most likely cause him to be put over the barrel, even at his age.

“You’ve got to be kidding. You know what that’ll do to you.”

I knew. “Mr. Holser, go to the duty officer, forthwith, and place yourself on report.”

“I will not.” Vax was taking a chance, but not a big one.

He knew as well as I that a middy who called on an officer for help to run his wardroom was finished in the service.

“Alexi.”

“Yes, Mr. Seafort?”

“Put your pants on, go to the duty officer, and tell him the senior midshipman reports a mutiny in the wardroom. Mr.

Holser is written up but refuses to obey a direct order to place himself on report. I request a court-martial to determine the validity of my allegations.”

“Aye aye, sir.” Alexi threw aside the covers and reached for his trousers.

“Belay that, Alexi. You can’t do it, Nick.” Vax’s tone was urgent. “It’ll ruin you too. You’ll never get command if you can’t even hold a wardroom. You won’t even get another posting!”

“That’s no longer your concern, Mr. Holser.” I remained icily formal; it was my only chance. “Mr. Wilsky.”

“Yes, sir?”

“Dress yourself. Go to crew quarters. Wake the master-at-arms . Have him bring an escort to the wardroom, flank.

“As for you, Vax, you are under arrest.”

“Aye aye, sir.” Sandy was so nervous his voice soared into the upper registers. Frantically, he began throwing on his clothes.

Alexi, dressed, headed for the hatch. Vax grabbed his arm in a huge hand. “Nick, call it off. This is a wardroom matter.

Settle it here, among us!”

I had him.

“It’s too late, Vax. You ignored my order. Let go of Alexi.” I lay motionless, under my covers.

“Hold off, Nick. Talk it through.” He hesitated.

“Please.” Vax knew that I’d throw away my career if the two junior middies went on their errands. He also knew that he himself now faced court-martial and almost certain imprisonment in the brig, if not summary dismissal from the Navy.

I made my tone reluctant. “Alexi, Sandy, sit down.” I turned to Vax. “I’ll turn the clock back, Mr. Holser. Twenty push-ups.”

He stared, trying to read me. I looked away. I didn’t care what he thought he saw in my face. Apparently my indifference convinced him; he got down on the deck. “We’ll settle this later, Nick.” It was a growl.

“Yes, we will.” I spoke with confidence I didn’t feel.

He gave me twenty push-ups. Good ones, like the Academy taught in basic. At the end he got up on one knee.

“Now twenty more.” This time I stared him straight in the eye.Having given in the first time he had little choice. Rigid with fury, he did twenty more push-ups.

“Thank you.” I looked at the two junior middies. “Back to bed, you two.”

Neither dared say a word. Vax was still a potent force in their lives. He stood up and yanked on his clothes. “It’s a good time for a walk, Nicky,” he spat. “Care to join me?”

At that moment I regretted not letting him order Sandy in and out of bed all night, if he wished. Vax was twenty kilos heavier, a head taller, and a lot stronger than I was. And two years older, as well. I was about to get the tar beaten out of me, and I had no choice but to go through with it. I got out of bed and put on my pants, socks, and shoes. I didn’t put anything over my undershirt; no point in ruining a dress shirt or jacket.

We strode in silence to the passenger exercise room on Level 2. At that hour, past midnight, it was deserted. He went in first.

I knew the best thing was to circle while he stalked me, and try to avoid his lunges. He knew I knew that. So the moment I was through the hatchway I hurled myself straight at him, fists flailing at his face. I got in a few good licks before he got his cover up and held me off. I backed away.

He came at me, livid with anger. I backed away again. He drove at me faster, and again I went right at him, hammering.

He caught me a good one on the side of the head that made me dizzy, but momentum carried me past his guard and I was all over him, pounding at his stomach, chest, jaw. Then I unexpectedly dropped down and rolled away.

He was disconcerted, as I wanted him to be. My only chance was to do what he least expected. He came at me warily this time, guard up. I went into karate position. He did the same. We both feinted. I fended him off, but he steadily advanced, pushing me toward the corner. I had no choice but to retreat.

The next few minutes were bad. He got in a lot of blows, knocking me down, slapping my head back and forth, slamming me into the partition, raining punches on my chest and arms. I wasn’t strong enough to hold him off so I concentrated on convincing him he was hurting me more than he really was. It wasn’t easy, because he hurt me plenty.

I staggered, apparently semiconscious, blood flowing freely from my nose and mouth. My legs buckled. He grabbed under my arms with both hands, holding me as I sagged. It was what I’d waited for. I drove my fist into his crotch with all the strength I could muster.

Vax bent over in reflex, let go to clutch himself. I backed away, wiping blood off my face. Damn, he could hit. Vax leaned against the bulkhead, his eyes half shut, face white.

My arms ached from the pounding they had taken. I didn’t have strength left to hit hard. So, clasping my hands together, I bent and, like a battering ram, ran straight at him. My shoulder smashed into his side. He went down. So did I. He was a rock.

Vax scrambled to his feet, a murderous look in his eye, fists clenched. I got up, put my head down, and rammed him again. This time he bounced off a bulkhead. My shoulder was numb. We both staggered to our feet. His nose bled from his impact with the bulkhead. I lunged again. He had both hands out, and fended me off. I put my shoulder down and dug in, straining to ram him.

“Wait!” His breath came hard.

I backed off. “Prong yourself, joey.” I lowered my head and charged. He tried to knee my face, but was too slow. I butted him in the stomach and he toppled over. I wondered if I had broken my neck. After a moment I managed to get up. So did he.

“Enough!” Vax covered his stomach with both hands, I leaned against the partition, trying not to black out. “Truce.” He held up his hand as if pushing me off. Iwaited, trying to catch my breath enough to answer. “I can’t take you, Nick. And you can’t take me. Truce.”

“No.” I drove at him again. I didn’t have much left but he was too busy clutching his aching ribs to fight back. He slid down to the slippery deck, then pulled himself back up.

“For God’s sake, Nicky, enough! Neither of us wins.”

I nodded. “Lay off Sandy,” I gasped. “You’re hazing too hard.”

“Hazing’s part of it.”

“Not that much. Haze him some, but lay off when I say.”

He nodded reluctantly. “All right. Deal.”

“I’ll leave you alone,” I said. “And you don’t look for trouble with me.”

“Deal.” He swallowed. Cautiously, he tried letting go of his stomach.

“And you don’t call me Nick in the wardroom.” If I didn’t get it this time, I’d never have another chance.

“No.” He looked stubborn. “Not that.”

I launched myself at him. He put out both arms to block me but my charge knocked him into the bulkhead. Instead of backing off I rammed him with my shoulder again and again, thumping his ribs and back. I wasn’t doing much damage but he was too exhausted to deck me.

My vision went red. I heard grunting, his or mine, as I felt myself slip into total exhaustion. Then I became aware that he held both my arms in his big hands, holding me at arm’s length away from his body. I was braced against the deck, straining to get at him.

“Truce,” Vax said again. “Truce–Mr. Seafort.”

I slumped back. “Name?” I managed.

“Your name is Mr. Seafort.” He didn’t look at me with fondness, but his expression held a wary respect I hadn’t seen before.

“Truce,” I agreed.

We staggered out of the room and back up to Level 1, neither saying a word. I went directly to the shower. I stood under the warm spray, watching my blood swirl down the drain to the recycler in the fusion drive chamber below. I didn’t pretend I was victorious.

I had survived. It was enough.

5

To my surprise, the greatest change in the wardroom wasn’t how Vax acted toward the other middies. He remained surly to them, and they were still cautious in his presence. It was not in how Vax acted toward me. He spoke to me as seldom as possible and rarely used my name, but when he did, it was Seafort and not Nicky.

No, the biggest difference was in how the other juniors acted toward me. Because I’d stood up to Vax and survived I was unquestionably in charge as far as they were concerned, and they were eager to win my approval.

Alexi in particular seemed to undergo a case of hero worship. He and Sandy straightened my bunk, crease-ironed my pants along with their own, and showed me unexpected deference. Though I tried hard not to let it show, I loved it.

Vax, for his part, eased off on his hazing. One day I came upon him forcing Alexi to stand naked in an ice-cold shower.

When I ordered him to lay off, he did, without argument.

Alexi stumbled quickly out of the shower room, blue with cold and trembling from humiliation. Perhaps Vax felt that having given his word he had to keep it, but my interference didn’t make him any more friendly.

I reported for watch each day, sometimes with Mr. Cousins, occasionally with Ms. Dagalow. With Lieutenant Cousins I sat stiffly, hoping to stay out of trouble. Ms. Dagalow, though no Dosman, chatted about puters, as she often did.

Though I didn’t share her interest, I enjoyed her company and did my best to please her by learning what I could.

The next week I was transferred to engine room watch.

There Chief McAndrews tried to teach me the intricacies of the fusion drive. I discovered that I had little aptitude for it.

By now I’d shown myself impossibly slow at astronavigation, thoroughly muddled as a pilot, and hopelessly inept as a drive technician. Vax was older, bigger, and stronger. Both Vax and Alexi were better able to handle the crew. I was proving incompetent at navigation, pilotage, engineering, and leadership. An ideal midshipman.

Except for chess. I could concentrate on that; I didn’t feel our thirty-second limit as pressure. I always looked forward to my afternoon game with Lieutenant Malstrom. But one day when we set up the board his manner was subdued. I led with queen’s pawn, and before I knew it I had trapped him in a fool’s mate in five moves. He was not a good player, overall, but he was far better than that.

We started to put away the pieces. “What’s wrong, sir?”

I had known and liked this man for months now, but nonetheless I’d taken a daring step. A middy does not ask a personal question of a lieutenant. It is not done.

Lieutenant Malstrom looked at me without speaking. He began unbuttoning his shirt. He pulled it out of his pants, rolled it up from his waist. He turned, showing me his side.

Just above his hip was an ugly blue-gray lump.

I met his eye. “What is it, Mr. Malstrom?” By not using his rank I was getting as close to him as I could. We were friends.

He said the words so quietly I could barely hear him.

“Malignant melanoma.”

“Melanoma T?”

“Doc thinks it might be.”

My breath hissed. The disease was an occupational hazard.

In Fusion, it was impossible to shield ourselves from the Nwaves that drove the ship, and over time N-waves transmuted ordinary carcinoma to the virulent T form that grew with astonishing speed.

Like all of us, Mr. Malstrom had shipped interstellar as an adolescent, and should have been nearly immune.

“At least they’re not sure, sir.” I tried to look on the hopeful side. Most forms of cancer were easily cured nowadays, hardly worse than a bad cold. But the new strain of melanoma didn’t respond well to drugs. The treatment of choice was still amputation of the affected part, where possible.I asked, “Have you been treated?”

“Tomorrow morning. Radiation and anticar drugs. They caught it early; Doc Uburu says I have a good chance.”

“I’m very sorry, sir.”

“Harv.” He caught my look. “Here in my quarters. My name is Harv.” He must really have been shaken. I forced myself to say his unfamiliar name.

“I’m sorry, Harv. You’ll be all right. I know you will.”

“I hope so, Nicky.” He tucked in his shirt. “Don’t mention it to the others.”

“Of course not.” The Captain would know, of course.

Perhaps the other lieutenants. But the middies need not be told, or the seamen.

“I’ll go on sick leave for a few days, in case the anticars get me down. You can come give me chess lessons.”

I grinned as I stood at the hatch. “Every day, sir.” I snapped him a salute. It was a sign of affection and he knew it. He returned it and I left.

“Lord God, today is January 2,2195, on the U.N.S. Hibernia.We ask you to bless us, to bless our voyage, and to bring health and well-being to all aboard.”

“Amen,” I said fervently. Lieutenant Malstrom was absent. Amanda and I were again at the same table. This time I was thrown in with a colonist family of five journeying to a new life on Detour, our port of call beyond Hope Nation.

The unspoiled resources of these newer colonies attracted many like the Treadwells, eager to escape the pollution and regimentation of overcrowded Earth. At home we had Luna, of course, and the Mars colony. But some people weren’t attracted to dome or warren life. They sought open space and fresh air that was ever harder to find.

Not everyone could emigrate, certainly. Only the wealthy could afford it. Though I admired the quest that was taking them sixty-nine light-years from home, I wondered how the Treadwells had managed it. She was a gaunt prim woman whose hands darted restlessly. Her husband, squat, swarthy and muscular, looked more a laborer than the habitat engineer the manifests showed him to be.

Their oldest children were twins poised on the edge of adolescence. Paula, wearing a shade too much shadow, and Rafe, all awkward knees and elbows, seemed so vulnerable they recalled my own painful thirteenth year, roaming Cardiff with my best friend Jason. I stirred uneasily, recollecting my discomfort at his hand on my shoulder, aware of his acknowledged sexual proclivity and dubious of my own. I also remembered, at Jason’s casual touch, Father’s silent look that spoke volumes of reproach.

Both Rafe and Paula seemed awestruck by Naval life and in love with anyone who wore the uniform. Rafe pestered me for information, as he had Doc Uburu and Ms. Dagalow before me. Paula asked about joining up, what Academy was like, how old you had to be to enter.

Ms. Treadwell frowned. “The Navy’s no place for a lady.”

“Oh, Irene.” Paula’s voice dripped with condescension.

“What about Lieutenant Dagalow, at the next table?”

I tried not to wince. I couldn’t imagine calling my own father anything but “Father” or “Sir”.

“Look into it when we get to Detour.” Their mother flashed me an apologetic smile. “You can’t enlist in the middle of a cruise.” Their faces fell. Another fantasy gone.

I tried to cheer them up. “That’s not quite true, Ms.

Treadwell. The Captain has authority to enlist civilians as officers or crew. It’s almost never done, but it’s possible.”

The Captain also had authority to impress civilians into service in an emergency, but I didn’t mention that.

The twins fell to talking among themselves. They decided to persuade Captain Haag to let them join up, with or without their parents’ permission. Their younger sister Tara, six, said little. We adults drifted into another conversation. Jared Treadwell asked, “Is it true, Mr. Seafort, that this ship is actually armed?”

“All U.N. ships have weapons, Mr. Treadwell.” I smiled.

“It’s an odd and ancient precaution. There’s nobody to use them against, except now and then a few planetside bandits, and the ship’s lasers are not designed for antiguerrilla operations. They’re like male nipples: standard equipment, but useless.”

My sally drew a nervous laugh from his wife. Groundside attitudes were fairly straightlaced. It was fun to scan old holovids about the Rebellious Ages, but I couldn’t imagine a young couple who showed up unmarried with a baby, or even tried to swim naked on a beach. Of course modern birth control has separated casual copulation, which is tolerated in any combination of sexes, from casual reproduction, which is not.

The next day all four middies had astronavigation drill with Lieutenant Cousins. I worked my problems as well as I could, while Mr. Cousins shook his head in disgust at my mistakes.

Vax got everything right, as usual. Then Alexi fouled up a really easy problem and put the ship dead in the middle of a hypothetical sun.

Lieutenant Cousins glared at Alexi’s console, withering contempt dripping from his every word. “You incompetent child! God damn your eyes, Mr. Tamarov, you’re hopeless!”

That was too much. Alexi knew it. So, belatedly, did Cousins. Even Vax caught my eye and slowly shook his head.

Alexi got to his feet, nervously drawing himself to attention. He had opened his mouth to speak when Mr. Cousins forestalled him. “I apologize, Mr. Tamarov.” He glanced around. “To you and to all present. I spoke out of anger and not intent. I mean no disrespect to Lord God.”

Alexi sat in relief, and there was silence in the cabin. I knew Lieutenant Cousins, for all his bullyragging, wouldn’t hold Alexi’s objection against him. Blasphemy was no more tolerated aboard ship than it was groundside. The lieutenant could find himself on the beach for that kind of talk.

For three days Lieutenant Malstrom showed no ill effects.

Then he took to his bed, his side bandaged. We played chess daily, sometimes two or three games. I didn’t quite let him win, but I tried some unusual variations I wouldn’t have risked otherwise. Sometimes they didn’t work.

A week later he raised his shirt to show me his side. The ominous blue mass was gone; in its place was a red welt that was fading in places to white. Unthinking, I clapped him on the shoulder. “It worked!”

He grinned. “I think so, Nicky. Doc says I should be all right.”

“Fantastic!” I jumped up, too excited to be still. “Oh, Harv, sir, that’s wonderful!”

“Yes. I have my life back.”

We were too keyed up for chess. Instead, we talked about what to expect on Hope Nation. We’d both seen the holovids but I’d never traveled interstellar before, and Mr. Malstrom hadn’t been to Hope Nation. He promised to take me sightseeing in the fabled Ventura Mountains during our stopover. I promised him a double asteroid on the rocks at the first bar we came to.

Happy and relaxed, I went back to the wardroom to change.

Vax lay on his side and glowered the whole time I was there.

I said nothing; he did likewise. By the time I left, my good cheer had evaporated.

Alexi had the middy watch when we Defused to search for Celestina.We were fortunate; though far away, her beacons registered on the sensors’ first try. Under Lisa Dagalow’s watchful eye, Alexi plotted a course to the derelict ship. The lieutenant rechecked his figures. They agreed with Darla’s; we Fused again, a short jump to where the abandoned ship floated.

I pulled watch two days later when we Defused once more.

Lieutenant Cousins and I were on the bridge waiting, as the Captain took the conn. “Bridge to engine room, prepare to Defuse.”

“Prepare to Defuse, aye aye, sir.” A moment passed.

“Engine room ready for Defuse, sir. Control passed to bridge.”

“Passed to bridge, aye aye.” Captain Haag glanced at his instruments, then ran his finger down the control screen.

Millions of stars burst forth on the bridge simulscreens. I knew I couldn’t spot Celestinaunaided, but my eyes searched nonetheless.

“Confirm clear of encroachments, Lieutenant.” The Captain waited.

Lieutenant Cousins turned to me. “Go to it, Mr. Seafort.”

His tone held a hint of impatience.

I checked the readouts as I’d been taught. I glanced again, in alarm. Something was there. “An encroachment, sir! Course one three five, distance twenty thousand kilometers!”

“That’s Celestina,you idiot.” Cousins’s scorn brought a flush to my cheeks.

The Pilot intervened. “Maneuvering power, Chief.”

“Aye aye, Bridge. Power up.”

The Captain watched, not interfering. He could maneuver his own ship, of course, but Pilot Haynes was aboard for that very purpose. With squirts of the thrusters, the Pilot eased the ship forward.

Lieutenant Cousins dialed up the magnification on the simulscreens. A dark dot became a blob, then a lump.

Abruptly Celestinaleaped into focus, and I saw for the first time the tragic wreck that had cost two hundred seventy lives.

She spun lazily on her longitudinal axis, crumpled alumalloy revealing a gaping hole in her fusion drive shaft. Tom and shattered metal protruded from both levels of the disk; the passengers and crew had never had a chance.

I was silent, a lump in my throat. Hundreds of colonists had sailed that ill-fated vessel. A Captain like ours. Seamen, engineers, midshipmen like ourselves. My eyes stung.

“Get back to work!” Lieutenant Cousins loomed over me.

“Watch your screens, you–you crybaby!”

“Belay that, Lieutenant!” The Captain’s voice stopped him cold.

From time to time I glanced up from my console to the simulscreen, on which the derelict slowly swelled. Soon, tiny portholes were visible against the white of the disk, shaded almost to black against the interstellar darkness. After a time even Lieutenant Cousins seemed affected; he fiddled with the magnification until suddenly he caught the lettering on the vessel’s side. He spun up maximum magnification, and the letters “U.N.S. Celestina”filled the screen. My breath caught. We were all silent now.

Pilot Haynes maneuvered the ship to within a half kilometer of Celestina.Then he turned the conn back to the Captain, who picked up the caller and spoke to the passengers, who would be crowding the portholes for the extraordinary view.

“Attention all hands. We have Defused. We are now at rest relative to U.N.S. Celestina,destroyed by the Grace of God one hundred twelve years ago this month. Many of us will never pass this place again. It has become custom, in ships sailing this road, to pay our respects to the memory of Celestina.All passengers who wish may go aboard. Our ship’s launch will ferry you across in groups of six. The trip will last approximately two hours. The Purser will announce the order of embarkation. That is all.” Captain Haag put down the caller and stepped to the front of his command console, staring somberly at the simulscreen, hands clasped behind his back.

“Will you go aboard, sir?” Lieutenant Cousins asked him.

“No,” Captain Haag said quietly. “I’ll stay with the ship.” He cleared his throat. “I went over on my last trip, four years ago. I’ll remember without seeing it again.” But his eyes were riveted on the derelict.

The duty roster was posted. The ship’s launch normally held ten. Each trip would be conducted by a lieutenant, accompanied by a midshipman and two seamen. Lieutenant Malstrom drew the first trip. Vax went with him. Two and a half hours later a subdued group of passengers returned, saddened and quiet. On the second excursion Sandy Wilsky went, with Lieutenant Cousins. I was scheduled for the third trip with Lieutenant Dagalow, and back on watch for the fourth.

When my turn came I suited up and joined the seamen helping passengers struggle into their unaccustomed suits.

For convenience, the launch traveled airless. Mrs. Donhauser was in our group, but I was too busy helping the others to say anything to her.

The launch berth was in Hibernia’sshaft, just forward of the disk. We trekked into the airlock joining the two sections of the ship, climbing awkwardly up into the shaft when the lock finished cycling. I felt my weight lessen as I dropped onto the deck of the shaft. Forward of me a hundred meters or so, the cargo hold was stuffed with medical equipment, precision tool and die-making implements, a hi-tech chip manufactory, and other supplies for the Hope Nation colony.

We seated the passengers. The launch’s transplex portholes offered a clear view, and the passengers huddled to peer through them. Lieutenant Dagalow dialed the bridge; a moment later the launch berth airlock slid open.

I glanced hopefully at the launch controls. Lieutenant Dagalow shook her head, smiled gently. “We don’t have time, Nick.” I flushed at the reminder of my incompetence, but merely nodded.

With a brief squirt of the maneuvering thrusters she propelled us out of Hibernia’sberth. The launch’s powerful engines throbbed, its nozzles directing the liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen reaction mass that propelled us.

Lieutenant Dagalow didn’t bother to compute a course as I would have had to; instead, she eyed the huge derelict and sailed by dead reckoning. It wasn’t quite by the book, but I envied her skill, and some part of me was glad I hadn’t attempted to pilot a craft with so many watching.

We drifted closer to the inert ship. Ms. Dagalow’s voice crackled in our suit speakers. “U.N.S. Celestinaembarked from Mars Orbiting Station May 23, 2083, with a crew of seventy-five men and women, including twelve officers. She carried a hundred ninety-five passengers, all of them colonists for Hope Nation.” She paused. “Jethro Narzul, son of the Secretary-General, was among them.” She throttled down the engines. We were rapidly approaching the derelict ship; time for braking thrusters.

At reduced speed we drifted close to the abandoned colossus. With a practiced skill I envied, Lieutenant Dagalow fired the maneuvering thrusters and brought us to rest relative to Celestina’sgaping lock. Our alumalloy hatch slid open and a seaman jumped the few meters to the ship, a coiled cable slung over his shoulder. He moored us tight to the safety line stanchion in Celestina’slock. As the derelict had no power, we couldn’t connect to her capture latches, but since everyone aboard was suited, we didn’t need an airtight seal.

Lieutenant Dagalow and a seaman boarded Celestinato help our suited passengers alight; the other sailor and I stayed in the launch to help them disembark. When all were safely aboard the derelict I joined the somber tour.

Lights had been strung every twenty meters or so. We stumbled along Celestina’ssecond-level corridor. The ship, of an earlier design, had but two levels in her disk. Debris must have swirled around the wreckage during the explosive decompression; much of it hung about where its inertia had brought it.

Celestinawas like nothing I had ever seen. Much of her disk was surprisingly clean and orderly. Lieutenant Dagalow opened a cabin hatch; inside, a neatly made bunk waited for its long-gone occupant. A suit folded on the dresser was undisturbed.

“The ship was entering Fusion when the accident occurred.

The drive exploded without warning. The shaft and the disk sustained heavy damage. Decompression was almost instantaneous.” He paused. “Today, rapid-close hatches divide the disk into sections. We believe many of you would now survive a similar accident.”

Mrs. Donhauser spoke up. “What caused the explosion?”

Ms. Dagalow shook her head. “The truth is, we don’t know.” I felt a chill. “The fusion drive has been redesigned several times since Celestinawas launched. No other ship has ever had a similar failure.”

She opened the hatch to the adjoining cabin. A rocking horse and a closet full of little girls’ clothes framed the hatchway. Sickened, I turned away.

“What happened to the people?” a passenger asked.

“They were given decent burial in space when the ship was rediscovered by the Armstrong.“ The legendary U.N.S. Neil Armstrong,Captain Hugo Von Walther commanding.

The search vessel that had found the long-missing Celestina,and later opened two new colonies for settlement. Her commander had fought a duel with a colonial Governor, served as Admiral of the Fleet, and had ultimately been elected Secretary-General.

Our seamen had strung a rope barrier to keep us from the damaged areas where ragged sheets of torn metal hung dangerously. We trekked up the ladder to Level 1. My breath rasped in my helmet. My suit’s defogger labored.

We gathered at the top of the ladder and moved as a group along Celestina’scircumference corridor. Ahead a pale light gleamed, reflecting the gray corridor bulkheads. “The bridge is just ahead,” said Lieutenant Dagalow.

We came to the open hatchway revealing the ghostly, deserted bridge. My breath caught. On the bulkhead outside the bridge hung the hundreds of slips of paper pictured so often in the holozines. We clustered at the bulkhead to read them.

“Robert Vysteader, colonist en route to Hope Nation, in memory of this poor ship, this fifteenth day of August 2106, by the Grace of God.” “Mary Helene Braithwaite, colonist in God’s hands, in memory of our brethren who died here.

December 11,211’.” “Ahmed Esmail, remembering Celes-tina.December 11, 2151.”

So they went. Each spacefarer who had come this lonely way had left a respectful mark to honor his predecessors who’d suffered disaster. Many of the visitors had gone on to Hope Nation or Detour, lived long lives and since died of old age.”Over here! Look!” We crowded round. The slip of paper was clipped just beyond the hatchway. “Hugo Von Walther, Captain, U.N.S. Neil Armstrong,in commemoration of our sister ship Celestina.God rest her soul, and all who sailed in her. August 3, 2114.” We trod the actual footsteps of Captain Von Walther. He had stood in this very spot the day he discovered Celestina,eighty-one years past. I tried to summon his presence. What a man he had been.