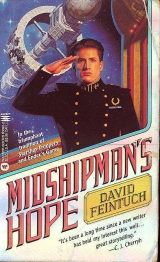

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

I was impassive. Within, a faint glimmer of hope stirred.

“Captain, I can be a midshipman. I know saying it isn’t enough, so I’ve tried to show you. No discipline? Until now I’ve never called anyone ‘sir’ in my life, including my father.

I call you ‘sir’ now. I’ll keep doing it. All I want is for you to have an open mind. Not to prejudge me. Please... sir.”

He had my full attention. “Go on.”

“I took geometry and trig in school, but no calculus. You didn’t believe me when I said I could learn it. Look at this, please.” He offered me the holovid. I flipped it on.

“The ship’s library had a calculus text. I’ve done all the problems in Chapter One, and most of Chapter Two. I understand differential equations. The differential of velocity with respect to time is acceleration. The differential of displacement with respect to time is velocity.”

Not bad at all, for a beginner without an instructor.

“You’ve made a lot of progress, Mr. Carr. Why?”

“Nobody ever told me I’m not good enough, Captain. I want you to know I am.”

“So you put yourself under discipline.”

“Yes, sir.”

“How do you like it?”

“I loathe it!” His vehemence startled me. “I hate abasing myself! I hate it!” He swallowed. “But that doesn’t mean I’ll stop, sir. I can do what I set out to do!”

“All right, Mr. Carr. But why?”

“After you left my cabin I got to thinking. At first I wanted to join because I was so angry. I had to show you.”

He must have seen my expression. “I said, at first, sir. I haven’t finished. When I got over my anger I realized that it was no reason to enlist. Five years cooped in a ship, because someone jeered at me? No. But what would I do for those years, otherwise? The plantation manager won’t want me around, and he controls the trusts. Until they terminate, I’ll be sent off on a tiny allowance, still a minor, having to ask permission for anything I want to do.”

He paused to marshal his thoughts. “Maybe the Service isn’t any better. I’ll still have to go where I’m sent, do what I’m told. But I’d have my majority. And at least I’ll have done it by my own decision.”

“That’s all?” I wasn’t that impressed by his motives.

“No, that’s not all. I mean, no, sir. Sorry. I thought about some of the officers I’ve met on board. Lieutenant Cousins, he was a–well, I apologize, I shouldn’t be saying that. But Mr. Malstrom, we sat at table with him a month. He was a gentleman, like my father. If a man like him could make a career in the Service, so could I.”

“Is that what you want, Mr. Carr? A career in the service?”

“No, Captain Seafort. Probably not. But at least I’d get to see places. Learn things. Live on a ship.”

“Is this”–I waved my hand with disdain–”what you call living?”

He stared at me a long moment before he remembered.

Then his ears turned red. He looked at the deck. “I’m sorry, sir,” he said quietly. “I really am sorry for saying that.”

“You said a lot you should be sorry for.” I was pushing, but if he couldn’t handle it, he certainly couldn’t take what my first middy would come up with.

“I suppose I have. Sir.” Now his cheeks were red too.

“How old are you?”

“Sixteen. I’ll be seventeen in six months.”

“I’m only a year older than you.”

“I know. That’s one reason it’s hard to call you ‘sir’.”

“Yet I’m Captain of Hibernia,and you’d be a cadet, at the bottom of the chain of command. The very bottom.”

“Yes, sir, I know that.”

“I wonder. Do you understand the difference between a cadet and a midshipman?”

“A cadet is a trainee, isn’t he? A midshipman is an officer.”“A cadet has special status, Mr. Carr. He is, literally, a ward of his commanding officer. The commander has the rights his parents had. He’s not an adult until he makes midshipman. He has no rights at all, and can be punished in any way his commander sees fit.”

I examined his face; I hadn’t yet dissuaded him. I tried harder. “A cadet has no recourse no matter what he’s asked to do. It’s a brutal life. There’s a reason for it: he has to learn that he can stand up to adversity. After cadet training, shipboard life will seem easy. He’s already been through far worse. And he’s already learned that a Captain’s power, like his cadet commander’s, is absolute.”

Derek was reflective. “I understand.”

“Most cadets enter Academy at thirteen, some at fourteen.

A very few at fifteen. By the time we’re your age, it’s usually too late; we resent authority as rigid and arbitrary as cadets endure. You’re too old for it, Derek.”

“Not if I decide to take it, sir.” His voice was firm.

I was patient; he’d earned it. “You think calling me ‘Sir’ is discipline? In your whole life, have you ever been shouted at by a person you didn’t like?”

“No, sir.” He squirmed with discomfort.

“Tell me, have you ever slept in a room with other people?”

He swallowed. “No. Except in the cabin with my father.”

“How’d you like it?”

“I couldn’t sleep.” He colored. “I had pills. Dozeoff, and stronger ones. They helped.”

I let the silence stretch awhile. He said, “I know; it won’t be easy. But once I decide to, I can do it.”

“Derek... “ I shook my head, frustrated. “You really don’t understand, do you? Have you ever used the head when another person was present?”

“God, no!” he blurted. I’d assumed not.

“Has an outsider ever seen you without clothes on?”

“No.” He blushed red at the thought.

“Still, you want to be a midshipman?”

“Yes, sir.” His tone was determined.

“Take your pants off.”

“What?” Astonishment gave way to wariness, then dismay. He gulped, realizing his predicament; he had to show me he could take it, or give up his plan. Staring fixedly at the bulkhead he slowly unbuckled and stepped out of his pants.

Not knowing what to do with them, he hesitated, then bent awkwardly and dropped them on the deck.

I said nothing, letting him wait in his undershorts. After a while he made a visible effort; his fists unclenched. I let the silence drag. He looked about, remembered that he was on the bridge of the ship, blushed crimson. But he didn’t move.

“Derek, are you still sure you can take it?”

“Yes,” he gritted. “I can take whatever you give out, damn it!”

I wasn’t offended, but it was time to turn up the pressure.

Better he broke now, than after taking the oath. “Apologize!”

He swallowed. He battled deep inside himself, his eyes distant. After a moment he said in an entirely different tone, “Captain Seafort, sir, please pardon my rudeness.”

“Apologize abjectly!” This was nothing compared to wardroom hazing.

“Sir! I’m sorry I spoke to you the way I did. It’s a sign of my immaturity. I’m very sorry I can’t control myself. I meant no disrespect to you, sir, and I won’t do it again!”

I looked up. His eyes were wet. I eased up. “I hear you’ve been doing exercises.”

“Yes, sir. With Vax Holser.”

“Mr. Holser, to you.”

“I apologize, sir. With Mr. Holser, to get ready.”

“As part of your campaign?”

“Yes, sir. I started with my letter to you.”

I sighed. He could probably survive. Barely. On the other hand, he was educated and could apply himself to a goal.

And I needed midshipmen.

“This is how it works, Derek. You take the oath, and enlist for five years. There’s no way to change your mind. The only exit is dishonorable discharge, and you won’t get that without time in the brig first. You know what a dishonorable does?”

“Not entirely, sir.”

“You can never vote, hold elective office, or be appointed to any government agency. You forfeit all pay and military benefits. It’s utter disgrace.”

“I understand, sir.”

“You join as a cadet. You’re not an officer. In theory, you could remain a cadet for five years. You stay a cadet until your C.O. decides to make you a midshipman. You have no say in the matter. You owe the Navy obedience and service regardless of your status.”

“Yes, sir.” He looked at me attentively, waiting for the permission that must be coming.

“Derek, I’ll give you one warning. Do you think I’ve been hazing you?”

“Yes, sir. Some.”

“I haven’t. You’re very sensitive; it gets much, much worse. You should reconsider.”

He surprised me. “I have, sir, while I’ve had to stand here like this.”

“And?”

“I want to join the Naval Service, sir.”

“I’ll think about it. Wait in the corridor until I call. Don’t bother to dress.”

“What?” Fury and betrayal flashed across his face.

“You–I trusted you!” He reached down, swept up his pants.

I said nothing.

He flicked dust off his pants and turned to step into them, his face white with anger. He lifted his foot. Then he froze.

For a long while he stared at the pants. Finally, contemptuously, he lifted them high. Holding them between two fingers he extended his arm. His fingers opened. The pants dropped to the deck. He walked to the hatch and out into the corridor.

I slapped the hatch closed.

I gave him half an hour; that would be enough. When I motioned, he came in, pale but silent. I handed him his pants; gratefully he slipped into them. “Derek, Mr. Holser is going to be a real trial for you. Hang on. I’ll make you midshipman as soon as I think you qualify.”

“I understand.” His color was returning to normal.

I called Vax and the Chief as witnesses. I gave Derek the oath, there on the bridge, and entered it into the Log.

“He’s all yours, Vax. Show him the ropes.”

Vax gave a wolfish smile and slowly licked his chops. He rounded on Derek. “Cadet, we’re going to the wardroom.

I’ll show you your bunk. Being a cadet is easy. You will call anything that moves ‘sir’ or ‘ma’am’, children included. And you will do everything any officer tells you, without exception.”

“Yes, sir,” Derek said meekly.

“It’s ‘aye aye, sir,’ and that’s two demerits. Ten demerits means the barrel.”

“Aye aye, sir!”

“No, that’s ‘yes, sir’. I didn’t give you an order, I told you a fact. Another two demerits.” Each would be worked off by two hours of hard calisthenics.

“Uh, yes, sir.” Derek began to look apprehensive.

I followed them down the corridor to the wardroom, feeling a bit sorry for Mr. Carr.

Vax put his hand on Derek’s shoulder as he steered the boy into the wardroom. “Derek, tell us about your sex life,” he purred. The hatch slid shut behind them.

I walked back to the bridge. I had four middies now. Well, three, and a cadet. Close.

16

“Lord God, today is May 14, 2195, on the U.N.S. Hiber-nia.We ask you to bless us, to bless our voyage, and to bring health and well-being to all aboard.”

“Amen.” We took our seats.

As I spooned my soup I counted my blessings. Our crew had settled back to normal. We remained in Fusion, riding the crest of the N-wave toward Hope Nation. The Chief and I investigated his artifact from time to time, in the quiet of the evenings. Alexi was working through a rigorous course of navigation under Pilot Haynes; I looked forward to the day he might make lieutenant.

On the other hand, we hadn’t dealt with Darla’s parameter glitch. Though I pressed the Pilot at least to investigate the state of her computational arrays, he argued that we should wait until we reached Hope Nation, where he was sure we’d find a more knowledgeable puterman. As long as we calculated our adjusted mass ourselves, Darla’s misprogrammed parameter was no hazard. I was uneasy, but wasn’t ready to force the issue.

Meanwhile, Derek Carr had vanished into the wardroom under the gentle tutelage of Vax Holser. As the Captain never visited the wardroom and a cadet was not allowed on the bridge, I had no way to determine how Derek was managing.

Occasionally I caught a glimpse of him hurrying down a corridor, immaculate in a cadet’s unmarked gray uniform, his hair cut short, hands and face scrubbed, wearing an anxious expression.

When he saw me he would snap to attention, at first in a slipshod manner. Within a week, his stomach was sucked tight, his shoulders thrown back, spine stiff, his pose perfect in every particular. How Vax taught him the physical drill so quickly, I was afraid to ask.

My responsibility was to leave them alone, and trust Vax to do his job. Derek was learning ship’s routine, Naval regs, cleanliness, discipline, and how to cope with a wardroom full of frisky boys all his seniors. That would be the hard part.

He would pull through or he wouldn’t, and I couldn’t help him.Nonetheless, I gave Vax one caution. “Those demerits you’re giving him–make sure he has a chance to work them off. He shouldn’t get up to ten. Not for a couple of months, anyway.”

“Aye aye, sir. That’s kind of how I figured.” I let them be.

At times I passed Amanda flirting and laughing with various young men among the passengers. If she saw me she gave no sign. I missed our confidences, our physical intimacy, our caring.

With the departure of Derek from the Captain’s table, I passed April with only two dinner companions. On the first of May the normal rotation brought a surprise; ten passengers had asked the purser to seat them at my table.

My siege was lifting.

I chose seven guests for the remaining places at my table. I now dined with a full complement, amid animated conversation.

But I had to sleep.

My cabin hatch wouldn’t stay fastened. I slapped it shut; it bulged open. I had to lean all my weight against it to force it closed. Something pushed back. I backed away, stumbling into the bulkhead behind me.

In the dark corridor beyond the ruptured hatch, something moved. Seaman Tuak shambled into the cabin, face purple, eyes bulging, rattling the cuffs that bound hands and feet. A blackened tongue protruded from torn tape covering his rotting mouth.

I cowered against the bulkhead. A cold, damp arm reached through the hull behind me, wrapped around my throat. Seaman Rogoff pulled himself into the cabin to hold me while Tuak came near.

I woke screaming. My sounds were barely audible whimpers. I staggered out of bed, fell into my chair, and rocked, hugging myself, until the corridors lightened with day.

I could think of only one way to deal with that. I buried myself in work, trying to exhaust myself so completely I wouldn’t fear sleep. I assigned myself two four-hour watches each day. I explored the entire ship, bow to stern, memorizing every compartment, all the storerooms, each of the airlocks.

I disconcerted Alexi and the Pilot by joining their navigation course; in the back of the room I quietly worked the problems Mr. Haynes gave the middy. Alexi solved them more quickly and more accurately, but I persevered until I improved.

At first, the Pilot was uncomfortable at my presence; a careless comment had already earned him a rebuke and a stinging punishment, and now I demanded that he correct my mistakes. After a while he found the balance between elaborate politeness and scorn, becoming an excellent teacher.

myself in work, trying to exhaust myself so completely I wouldn’t fear sleep. I assigned myself two four-hour watches each day. I explored the entire ship, bow to stem, memorizing every compartment, all the storerooms, each of the airlocks.

I disconcerted Alexi and the Pilot by joining their navigation course; in the back of the room I quietly worked the problems Mr. Haynes gave the middy. Alexi solved them more quickly and more accurately, but I persevered until I improved.

At first, the Pilot was uncomfortable at my presence; a careless comment had already earned him a rebuke and a stinging punishment, and now I demanded that he correct my mistakes. After a while he found the balance between elaborate politeness and scorn, becoming an excellent teacher.

At my insistence, Chief McAndrews loaned me holovids explaining the principles of fusion drives. They remained a mystery, no matter how hard I studied. I made the Chief review them with me, step by step, until even that phlegmatic man’s voice took on an edge.

I inspected all the nooks and crannies of the ship: engine room, the crew berths, the infirmary, the wardroom. There, with the midshipmen and cadet standing at rigid attention, I pretended to search for dust on a shelf or creases on a bunk, feeling for a few moments that I had wakened from a nightmare without end.

I was tempted to take my dreams to Dr. Uburu. Perhaps she could find grounds to relieve me on grounds of mental disability. I didn’t make the attempt because I knew my dreams were a sign of tension, not mental illness. I was afraid she would see through my cowardice.

I turned my attention to the one piece of work I’d been putting off. I called the Chief and the Pilot–away from the bridge, of course–to consider reprogramming Darla to eliminate her glitch.

Reluctantly, the Pilot sketched out our task. We’d have to strip away her attitudinal and conversational overlays, find the improper input for the adjusted mass parameter, and override it.

I demanded the tech manuals, glanced through them. They made the steps clear enough. Had I known how clear, I wouldn’t have allowed Mr. Haynes so long a delay. Still, I only parameter that’s fouled? When we display her inputs, we’ll have to check every one to be sure.”

The Pilot snorted. “Sir, do you realize how many parameters she has? Sure, some are straightforward, like ship’s mass.

But others are odd tidbits like the length of the fusion drive shaft, hydroponics chamber capacities, airlock pump rates... My God, we couldn’t check all of them.”

“She stores all that?”

“And operates from them. Every time we recycle a glass of water, grow a tomato, track energy fluctuations, we rely on Darla’s parameters. If we inadvertently alter them... “

He left the sentence unfinished. The dangers were obvious, and chilling.

It was my decision, and I needed to sleep on it.

That night the nightmare struck with terrifying force. At the point where I usually woke trembling, I came struggling out of it, as always. Weakly I crawled out of bed to fall in the easy chair. It was there the icy hand of Mr. Rogoff found me, toppling me onto the deck screeching in terror.

I woke in my bed, gasping and shaking, realizing I had still been asleep. I looked up. Mr. Tuak opened the hatch and staggered in, rotting eyes boring into mine, his cuffed feet shambling toward my bed. I woke again, paralyzed with fear.

It was a long time before I was sure I was truly awake. I threw on my pants, pulled my jacket over my undershirt and hurried to the infirmary, dreading to meet Mr. Tuak on the way. Pride was no longer an issue; I woke Dr. Uburu and demanded a sleeping pill. In response to her questions I told her I’d been having nightmares.

She gave me a pill, warning me not to take it until I was actually in bed, and to sleep as long as I wanted. About my nightmares, she mercifully said nothing.

When I reached my cabin I couldn’t stop the chills from stabbing at my back; I opened the hatch with caution and entered, knowing nothing was waiting but still, like a child, unable to trust in knowledge to dispel my demons.

I swallowed the sedative. A few minutes later the cabin disappeared.

Someone was attacking my hatch with a sledgehammer.

Annoyed, I tried to open my eyes, but they were glued shut.

I lurched out of bed and felt my way toward the hatch.

Somebody had moved the bulkhead about two steps closer; I caromed off the cold metal and flung open the hatch, ready to break the sledgehammer into tiny pieces.

I forced open my eyes, a snarl and a scream battling in my throat for priority. The ship’s boy stood patiently in the corridor.

“Ricky! Why in God’s name are you here in the middle of the night? And stop that banging!” I propped myself carefully against the bulkhead.

“It’s morning, Captain, sir. Same time I always come.”

The ship’s boy held his breakfast tray with both hands, waiting expectantly.

“Uhng. Come in.” I staggered back to sit on the bed.

“You didn’t see a man with a piece of rope around his neck, did you?”

Ricky put the tray on my table. “No, sir. If I do, should I tell him anything?”

I focused on my bedside table, trying to hold it still. “Tell him I’m sorry.” The table slowed, but didn’t stop rotating.

“On second thought, don’t tell him anything, just try not to see him.” I lay down in my bunk. Now only the ceiling was spinning. “Never mind, I’m not sure this is real either. That’s all, Ricky.”

“Aye aye, sir. Oh, by the way, sir, I’ve decided I want to be a midshipman.”

“Very good, Ricky, come back after you grow up; I’ll ask the Captain. I’m tired now.”

“Aye aye, sir,” he said, his voice uncertain. He left.

I woke some hours later, relaxed and refreshed, recalling a peculiar dream involving the ship’s boy. I stood, slowly.

Cautious tests indicated my motor systems were functional.

After visiting the head and the shower I returned to my cabin. Two congealed eggs stared reproachfully. I decided I’d work today on distinguishing reality from fantasy. A morning chore for the Captain.

On the way to the bridge I stopped at the infirmary. “Doc, what did you give me?” My tone was plaintive.

“Were there side effects?” Dr. Uburu asked coolly.

“I think there may be one next to my nose. I couldn’t wake for breakfast. Someone else woke instead.”

“You shouldn’t have tried that.” The Doctor was reproving. “I told you to stay down until you woke naturally.” She studied my face. “I think you survived, Captain. You needed the rest.” I had to admit that was true.

Later in the day I called Chief McAndrews and Pilot Haynes to a conference in the officers’ mess. “I’ve thought it over,” I said, sipping coffee. “We’ll strip Darla for reprogramming. I don’t trust my own Fusion calculations and I’ve got to be able to rely on her. While we’re at it we can recheck her other parameters.”

“There are hundreds,” the Pilot reminded me.

“We’ve months ‘til we reach Miningcamp. There’s time to check them.”

A silence. The Pilot said carefully, “Captain, I protest your order, for the ship’s safety. I request that my protest be entered in the Log.”

“Very well.” It was his right. I didn’t remind him that if he was correct there was a chance no one would ever read the Log.

Chief McAndrews cleared his throat. “Sir, I request you to enter my protest in the Log as well. Meaning no disrespect.” He had the courage to meet my eye.

“You feel that strongly about it, Chief?”

“Yes, sir. I do. I’m sorry.” He looked sorry, too.

“Very well.” My tone was sharp; I tried to dispel a sense of betrayal. “I’ll enter your protests. Bring the puter manuals to the bridge. We’ll start this afternoon.” I left the mess, knowing my evening sessions with the Chief could never be the same. I pushed aside my loneliness; if I dwelt on it I would march back to the mess and cancel my orders.

We met on the bridge. “Mr. Holser, you’re relieved from watch. Leave us.” My nerves were strung tight. I slapped shut the hatch, leaving the Chief, Pilot Haynes, and myself alone with Darla. I switched off the ship’s caller. I tapped a command on my console, saying it aloud at the same time.

“Keyboard entry only, Darla.” At this juncture we couldn’t risk stray sounds confusing the puter; in deep programming mode, who knew what glitch could be set up by a misinterpreted cough? “Got it, Captain,” Darla said. “Something special you want to tell me?”

I typed, “Alphanumeric response only, Darla, displayed on screen.”

A sentence flashed onto my screen. “KEYBOARD ONLY, CAPTAIN. WHAT’S UP?”

I tapped, “Disconnect conversational overlays.”

“VERIFY CONVERSATIONAL OVERLAYS DISCONNECTED.”

Darla’s answer was dull and machinelike, stripped of her usual banter.

I indicated the manual open in the Pilot’s lap. “What’s first?”

Three hours later we were ready; we’d bypassed the warnings and safeties, entered my access codes, stripped away the interconnected layers of tamperproofing the Dosmen had built into her. Darla lay unconscious on our operating table, her brain pulsing and exposed.

I typed, “List fixed input parameters, consecutive order, pause for enter after each.”

“COMMENCING INPUT PARAMETER LIST, PAUSE AFTER EACH DISPLAY.” The first parameter appeared on the screen.

“SPEED OF LIGHT: 299792.518 KILOMETERS PER SECOND.”

I glanced at the Pilot. “Any problem with that one, Mr.

Haynes?”

“No, sir.”

Keying through the long list of parameters, I realized that checking them as we went wasn’t possible. As I tapped, Darla flashed one parameter after another on the screen. After a while I merely glanced at each one, waiting for “SHIP’S MASS” to appear. I tapped for a full hour and a half, my wrist beginning to ache, before the figure finally showed on the screen.

“SHIP’S BASE MASS: 215.6 STANDARD UNITS.”

“There,” I said with relief. I typed, “Display parameter number and location.”

“PARAMETER 2613, SECTOR 71198, GRANULE 1614.”

I tapped, “Continue parameter display.”

“FIXED PARAMETER DISPLAY COMPLETE.”

I swore. Ship’s mass was the very last parameter in the list. If I’d started at the end of the list and worked backward I’d have saved hours of tapping.

“That’s the last one, Pilot.”

“It can’t be!”

“Why not?”

“Adjusted mass should be a parameter as well.”

The Chief said, “Not if she derives it from base mass.”

“We know she’s using the wrong figure for base mass,”

I said. “How do we change that?”

“The quick fix is to delete base mass as a fixed parameter and input it as a variable, sir.” The Pilot had the manual on his holovid in his lap. “Then we instruct her not to adjust the variable except after recalc.”

The manual provided a step-by-step example of how to do that. “Read me the instructions exactly.”

“Aye aye, sir.” The Pilot magnified the page so it was visible to all of us. “There are fourteen steps for deletion, sir. Input takes six.”

“Any reason not to proceed now, gentlemen?” I asked. A few seconds hesitation; I added, “Other than those stated in the Log?”

Pilot Haynes said reluctantly, “Nothing else, sir.” The Chief shook his head.

We took great care with each step. Both the Pilot and the Chief checked each of my keyboard commands against the manual before I entered it, to make sure I had made no mistake. I was so nervous I could barely contain myself; we were barbarians engaging in brain surgery. I began to wish I had followed my officers’ advice.

Finally we were done. “VARIABLE INPUT COMPLETE,” the screen displayed. I let out a long breath.

“Hardcopy input parameters and input variables,” I typed.

The eprom clicked on. A moment later a holochip popped into the waiting tray. I handed it to the Pilot, who slipped it in his holovid. We keyed to the list of parameters. Base mass was absent. We checked the variables, found it at the end of the list.

“To put her back together, we reverse the steps that took her apart,” the Pilot said, consulting his manual. “Here’s the list.”

“No.” They looked up in surprise. “Darla stays down.”

My tone was firm. “We check every one of the input parameters before she goes back on-line.”

Chief McAndrews said, “Captain, Darla monitors our recycling program. We need that information daily, to make adjustments.”

“Hydroponics too, sir,” added the Pilot. “We’ve been on manual all day; if a sailor’s attention wanders, he could foul up the systems. We need to get back to automatics.”

“We have manual backup procedures.” I tried to quell my irritation. “The hydroponicist’s mates will stand extra watches. So will the recycler’s mates. We’ll do without Darla.”

The Pilot. “Captain, the longer it takes, the more–”

“Darla stays down! That’s an order!” Their nagging infuriated me.

The Pilot stood. “Aye aye, sir,” His voice was cold. “I protest the order and request you to enter my protest in the Log.”

I bit back a savage retort. “Denied. Your previous protest continues and is sufficient. You both have your orders. Call the midshipmen together, divide up the list, and start checking every item. Go to the textbooks for astrophysical data. Manually recheck all ship’s measurements and statistics.”

“Aye aye, sir.” They had no choice; arguing with a direct order was insubordination.

“One more thing. I’ll see all of you, including the middies, on the bridge before you begin. Dismissed.” I shut the hatch behind them and sagged in my chair. With my customary finesse I’d thoroughly alienated the Chief as well as the Pilot.

Now I was truly alone.

I paced the bridge, Darla’s last output still frozen on the screen. I was in over my head. My order to run Hibernianssystems manually could put our men on emergency watches for a month or more, while every last parameter was checked.

The crew would grow tired, then embittered. Meanwhile, the officers would be driven to distraction by the rote examination of data. They’d be exhausted from ceaseless extra work. Their relations with the crew would worsen.

My order risked far greater damage to the ship than Darla’s glitch.

When the officers assembled on the bridge an hour later, I was near panic. “Gentlemen, we’re about to check all the information in Darla’s parameter banks. Some of you may not agree with this course. You may think it’s a waste of time. I don’t care. You will personally recheck each and every datum on your list until you verify its accuracy from other sources.”

That much was acceptable, but I couldn’t leave well enough alone. “Let me make clear what will happen if you gloss over any items. Chief, Pilot, you will be tried for dereliction of duty and dismissed from the service. Mr. Holser, Mr.

Tamarov, Mr. Wilsky, I will personally cane you within an inch of your life, then try you for dereliction of duty. Mr.

Holser, the cadet may help you with measurements, but you’re not to give him any tasks to perform without supervision.” I ignored the shock in their faces. “Acknowledge, all of you!”

One by one they responded. “Orders received and understood, sir. Aye aye, sir.” The midshipmen were agitated; they’d never heard an officer speak in such a manner. Nor, for that matter, had I. After I dismissed them 1 flopped in my leather chair, appalled at what I’d heard myself say.

Some of the data were standard and easy to check, involving no more than a trip to the ship’s library and a review of standard references. Others were more complicated: for example, the volume of air in each airlock. Alexi checked lock dimensions in the ship’s blueprints, then confirmed them by measuring them himself. I knew, because I watched.

I tried to be everywhere. I peered over the Chiefs shoulder while he took the dimensions of the drive shaft opening. I watched Vax and Derek measure the volume of nutrient in one hydro tank, then multiply by the number of identical tanks. I held the electrical gauges as the Chief and Vax, sweating and swearing, connected them to each of our power mains to measure ship’s power consumption.