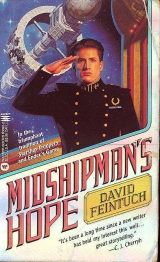

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

I went back to my cabin. I debated dress whites and decided against them; they would impress no one. I rummaged in my duffel for my unused wallet, checked to see that it still held money. As I’d be going shoreside I pinned my length of service medals to my uniform front, made sure my shoes were well shined.

On Level 2, passengers milled about the aft airlock for a look at the station, though they wouldn’t begin to disembark for hours. I went to the forward lock, where crews were already off-loading our cargo. Holovid in hand, I straightened my uniform and clambered through the lock.

“This way, Captain Seafort.” An enlisted man led me through the unfamiliar wide gleaming corridors and hatches of Orbit Station to the Commandant’s office. The design of the station was much like our disk, though larger in all respects. Higher ceilings, wider corridors, larger compartments.

Hundreds of people worked and lived in this busy shipping center. Cargo for Detour, Miningcamp, and Earth was transshipped through Orbit Station. Passengers disembarked here, before boarding other vessels to travel onward. Small shuttles journeyed back and forth daily to the planet’s surface. A typical orbiting facility for our interstellar Naval liners.

“I’m General Tho.” A small man, with a neat mustache above thin lips, and a receding hairline emphasized by wavy black hair. He eyed me dubiously. “You command Hiber-nal”“Yes.” I matched his abruptness with my own.

“Your shuttle will be ready in a few minutes.” After a moment he unbent perceptibly. “What happened to your officers?”

I sighed. I’d have to repeat the tale often enough. I explained.

When I was finished he shook his head. “Good Lord, man.”

“Yes. That’s why I want to report to the Admiral right off.”

His reply was cut short by the corporal who appeared in the doorway. “Shuttle is ready, sir.”

He shrugged. “Better go, Captain. I put you ahead of the passenger buses.”

“Thank you.” I followed the corporal down three levels, to a shuttle launch berth. It was similar in layout to Hibernia’slaunch berth, though on a far larger scale. It was designed to receive the great airbuses that shuttled passengers to and from the surface.

I grinned to myself; if I’d required Vax to polish this berth, he’d have marched right out the airlock. My grin faded; I recalled another man leaving an airlock, by my act. Sickened, I closed my eyes.

The shuttle was a sporty little six-seater with retractable wings, its jet and vacuum engines sharing the available bow space. I ducked and climbed aboard.

“Buckle up, Captain.” The pilot wore a casual jumpsuit and a removable helmet. He strapped himself in securely, more concerned with atmospheric turbulence than decompression. I followed his example. He flipped switches and checked instruments with the ease of long familiarity, waiting for the launch berth to depressurize.

“Lots of traffic these days?” I asked, mostly to make conversation.

“Some. More before the sickness.” He keyed his caller.

“Departure control, Alpha Fox 309 ready to launch.”

“Just a moment.” In a few moments the voice returned.

“Cleared to launch, 309.” The shuttle bay’s huge hatches slid open. Hope Nation glistened through the abyss, green and inviting.

Our propellant drummed against the berth’s protective shields as the shuttle glided out of the bay. Once clear of the dock the pilot throttled our engines to full. We shot ever faster from the station, approaching Hope Nation at an oblique angle until we encountered the outer wisps of atmosphere. The pilot hummed a tune I couldn’t recognize as he flipped levers, eyed his radars, swung the ship around with short bursts of his positioning jets to be ready to fire the retro rockets.

I asked loudly, “What did you mean, before the sickness?”

The first buffets of atmospheric turbulence rumbled the hull.

The pilot spared me a glance. “Didn’t you hear? We had an epidemic a while back, but it’s under control now.” He set the automatic counter, his hand poised to fire the engines manually if the puter didn’t turn them on.

“What kind of–”

“Not now. Wait!” The pilot’s full attention was on the puter’s readout. The retro engines caught with a roar at the exact moment the counter hit zero. His hand relaxed. “You never know about these little shipboard jobs!” He had to shout over the increasing din. “Not reliable like the mainframes you joes travel with!”

As we descended, Hope Nation lost its spherical shape.

Ground features emerged through scattered layers of clouds.

Here and there I could spot a checkerboard of cultivated fields, though most of the planet seemed lush and verdant.

Though I’d expected something of the sort, still I marveled at the sight of a planet so many light-years from home, whose ecology was carbon-based like our own. Hope Nation’s trees and plants supplied no proteins or carbohydrates we could digest, but they grew side by side with our imported stock.

No native animals, of course. No nonterrestrial animals had ever been found, other than the primitive boneless fish of Zeta Psi.

“Sorry,” the pilot shouted over the engine noise. “What were you saying?”

“What kind of epidemic did you have?”

“Some sort of mutated virus. It killed a lot of people before we found a vaccine. I don’t know much about it, except everyone gets a shot when they put down at Centraltown.”

“Is that where we’re landing?”

“Of course. All arrivals from the station go there. Customs, quarantine, everything’s at Centraltown.”

“Right. Of course.” I’d looked it up, but it was hard to digest a whole culture in an hour of holovid.

“Say, how’d you get to be a Captain, anyway?”

I sighed. It was going to be a long shore leave.

A few minutes later he deftly flipped the shuttle into glide mode and rode her above the flat plain toward the seacoast skirting the sparkling waters ahead. The jet engines kicked in a moment after the flipabout, making us a jet-powered aircraft.

Naturally, the pilot spotted the runway long before I did.

After all it was his home turf. The shuttle’s stubby wings shifted into VTOL mode as we bled off speed. The pilot timed our arrival over the runway perfectly; we were almost stationary as he dropped us gently onto the tarmac, the shuttle’s underbelly jets cushioning our fall.

“Welcome to Hope Nation, Navy!” He gave me a smile as he killed the engines. “And good luck.”

“I’ll need it.” I opened the hatch and climbed down, straightening to take my first breath of air in another solar system. It smelled clean and fragrant, with a scent I couldn’t quite place, like fresh herbs in some exotic dish. The sun, a G2 type, shone brightly, perhaps a bit more yellow than our own.I gawked like a groundsider on his first Lunapolis vacation.

My step was light and springy, a result of Hope Nation’s point nine two Earth gravity. The planet was actually twelve percent larger than Earth but considerably less dense.

My Naval ID took me through customs with no fuss. The quarantine shed was a ramshackle structure just off the runway, between the ships and a cluster of buildings. The nurse was friendly and efficient; I bared my arm; he touched the inoculation gun to my forearm and it was done.

I felt for my wallet. On this planet I was a greenhorn. I had no idea where I was going or how to get there but I assumed my U.N. currency would solve the problem. “How do I get to Admiralty House?”

“Well... “ The nurse squinted into the bright afternoon sunlight. “You could walk over to that terminal building there, go through to the other side, and rent an electricar. If they have one left, that is, there’s only seven. Then you turn left at the end of the drive, go to the first light, and turn left again and go two blocks.”

“Thanks.” I started to walk away.

“Or you could walk across the runway to that building over there. That’s Admiralty House.” He gestured to a twostory building seventy yards away.

“Oh.” I felt foolish. Then I grinned in appreciation; he must have perfected his routine on a lot of novices. “Thanks again.” I started across the runway, holovid in hand.

Now I wished I’d chosen to wear my dress whites, but I realized I was being silly. Stevin Johanson, Admiral Commanding at Hope Nation Base, wasn’t about to be impressed by dress whites adorning a fumbling ex-midshipman.

An iron fence surrounded the large cement block structure.

I unlatched the gate; a well-worn path across the unmowed yard led me to the front of the building. The winged-anchor Naval emblem and the words “United Nations Naval Service / Admiralty House” greeted me from a brass plaque anchored to the porch.post.

Had the brass plate been smelted here, or had they shipped the sign across light-years of emptiness to add majesty to the facade of colonial Naval headquarters? At the tall wooden doors with glass inserts at the top of the porch steps, I tucked at the corners of my uniform and brushed my hands through my hair. I took a deep breath, and went in.

A young man in shore whites was dictating into a puter at a console in the lobby. “Can I help you, sir?”

“Nicholas Seafort, Hibernia,reporting to Admiral Johanson.”

“Oh, yes, we were expecting you; General Tho called ahead. Captain Forbee will see you now.” He led me up redcarpeted stairs, along a hall to an office with open windows overlooking the sunny field. “Captain Seafort, sir.”

I came to attention. “Nicholas Seafort reporting, sir. Senior officer aboard Hibernia.”The young Captain behind the desk stood quickly and saluted. He squinted from weak, puzzled eyes. A youngish man, who’d started running to fat. “Shall we stand down, then?” It was an odd way to release me, but perhaps colonial customs were different. We relaxed. He indicated a seat.

“Thank you. Will I be reporting to you or directly to Admiral Johanson?”

He gave me a sad smile. “Admiral Johanson died in the epidemic.”

“Died, sir?” I sat. So much death...

“He caught the virus. One day he just dropped, like everyone else who had it.”

“Good Lord!” I could think of nothing else to say.

“Yes.” He looked unhappy. “So I’ve been running the Naval station. I sent word on the last ship out. It’ll be two years before his replacement arrives.”

“Very well, sir. I’ll report to you. I’m sorry I’m not better organized, but most of it is in the Log.” Afraid he’d stop me before I could get the whole sordid tale off my chest, I let my words tumble, summarizing what had happened aboard Hibernia.I spared myself nothing, glad now to have it over with. “Captain Haag’s loss and the lieutenants’ deaths were an act of Lord God,” I finished. “But I take full responsibility for the deaths of Midshipman Wilsky, the seamen, and the passengers.”

He was silent a long time. “Terrible,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“But you don’t know the half of it.” He stood and came around from behind the desk to where I sat, cap on my knee.

He bent and peered at my length of service medals. As if to confirm my story, he asked, “When did you say your last lieutenant died?”

“March 12, 2195, sir.”

“That’s in the Log?”

“Yes, sir.” I slipped the chip into my holovid, handed it across to him.

He sat at his desk, flipped through the entries until he came to the month of March. He shook his head as he reached the relevant passages. “It wasn’t June, was it? You became Captain in March.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, puzzled.

“That’s it, then.” Captain Forbee turned to look out the window. Facing away he said, “Hope Nation is still a small colony. We don’t have much of a Naval Station. No interstellar ships are based here; we’re not big enough to warrant it.

Admiral Johanson was a caretaker with seniority in case it might someday be needed; to resolve a dispute between two captains, for instance. Or to appoint a replacement in case a Captain died or was too ill to sail.”

“Yes, sir.”

“He had three Captains in system. One of them, Captain Grone–it’s an embarrassing incident, we did our best to hush it up–he went native almost a year ago. He and his fiancee stole a helicopter and flew to the Ventura Mountains.

Disappeared. We’ve never been able to find them. An unstable type, a lot of us thought. The second is Captain Marceau, from Telstar.Sixteen years seniority.”

Good. He or Forbee would replace me. My nightmare was over. “Where is he, sir?”

“The bloody fool had to go cliff-climbing on his shore leave. Six months, and he’s still in coma. Admiral Johanson gave Telstarto Captain Eaton last spring. They sailed to Detour, then headed for Miningcamp and Earth.”

“They never reached Miningcamp.”

“Yes, your Log makes that clear.” He sighed. “Eaton’s a reliable man. If he bypassed Miningcamp, he must have a reason.”

If that’s what he did, I thought silently. If Darla was glitched, how many other puters were, as well? I put aside the thought. “Sir, how many officers here are rated interstellar?”

He shook his head gloomily. “I said you didn’t know the half of it. Nobody. We have interplanetary Captains, of course, but why would anyone rated interstellar stay in this backwater?”

“You could go yourself, sir. Hibernianeeds a real Captain.”

“I told you we had no one, Mr. Seafort. You know how I came to Hope Nation? I shipped out as a lieutenant. My wife Margaret was among the passengers. I timed it so my hitch was up and I could resign my commission when we docked.

I’ve been a civilian for seven years, but after Admiral Johanson sent Eaton with Telstar,he reenlisted me so there’d be someone on staff who’d been interstellar.”

Did Forbee expect me to solve his problems for him? “You could appoint my lieutenant–I mean, my first lieutenant-as Captain, sir, and then relieve me.”

He stood tiredly. “You still don’t understand. Admiral Johanson gave me Captain’s rank at my reenlistment. To be precise, on June 6, 2195. Sir.”

“No!” I stumbled to my feet, overturning my chair. It was as if Seaman Tuak had shambled through the hatch, when at last I’d imagined myself safe.

“Yes, sir. You’re senior officer in Hope Nation system.”

23

I sat despondent while evening darkened outside the window, unnoticed.

We’d been over the regs a dozen times. I couldn’t find an escape.

“Governor Williams–”

“Is a civilian, sir. He doesn’t have jurisdiction over the Navy.” Captain Forbee must have studied every line of the regs as I had, hoping to escape his unwanted responsibility.

The relief he’d have felt when he found I had more interstellar time as Captain than he... “Governor Williams can no more appoint a Captain than you can set local speed limits,”

he added.

“You made your point!” Abashed, I lowered my voice.

“I can resign.”

“Yes, sir. Nobody can stop you.” He’d said it correctly.

Resigning for any reason except disabling physical illness or injury, or mental illness, was dereliction of duty. The regs I’d sworn to uphold required me to exert authority and control of the government of my vessel until relieved by order of superior authority, until my death, or until certification of my disability.

But no one could stop me from violating my oath.

“I won’t put up with this!” I glared at Forbee. “Someone in Hope Nation system must be rated interstellar, damn it!”

I was so frustrated I skirted blasphemy without caring.

“I’m afraid not, sir. Believe me, I’ve looked.”

“You have captains with interplanetary ratings. Any of them would be senior to me.”

“In service time, yes, sir. But any Captain Interstellar is senior to a Captain Interplanetary. Surely you know that.”

“Don’t tell me what I know!” I snapped.

“I’m sorry, sir.” His tone was placating.

We sat in silence. At length I said, “Hiberniacan’t sail with me at the helm. That’s too dangerous. And if Telstar’smissing, she may never have even made Detour; we must sail. Our supplies would be needed there more than ever.”

Forbee folded his arms. “I agree.”

“Will you search for Telstar?”He looked surprised. “That’s for you to decide, sir. You’re in charge.”

I stood, fists bunched.

“You’re senior,” he blurted. “I can’t help it. The naval station is under your command.”

“Of all the... I’ll–by Lord God–” With an effort I brought my speech under control. “These are my instructions: run the naval station exactly as you would if I hadn’t arrived! Is that clear?”

“Yes, sir. Aye aye, sir!”

“Are you going to search for Telstar,Forbee?” I was too put out to use his rank.

“We have nothing to send after her, sir. None of our local ships have fusion drive.” That was that. Search and rescue were impossible.

We couldn’t just ignore the fact that Telstarwas missing.

Word had to be sent back to Admiralty at Luna, but Hiberniawas the next ship scheduled to return–in fact, the only fusion vessel in the system. My mind spun. That meant I had to-Enough was enough. “By Lord God, I’ll resign!”

“Will you, sir?” His voice was without inflection.

“Yes. Right now. Give me my Log; I’ll write it in.” It was time to free myself from this madness. If Admiralty tried me for dereliction of duty, so be it; at least I’d kill no more passengers and crew by my stupidity. If the regs required me to remain Captain, the regs were wrong. I would follow my conscience.

I keyed the holovid to the end of the most recent entry, tapped the keys. “I, Nicholas Ewing Seafort, Captain, do hereby res–” I halted, the hairs raising on my neck. Slowly, I turned, called by the familiar touch of Father’s breath as he watched me struggle with my lessons.

Day after day, in the cold dreary Welsh afternoons, I worked my way through the texts, struggling to master new words and ideas, scrawling answers into the worn notebooks he bade me use. When I was right he gave me another problem. When I made a mistake he said only, “That’s wrong, Nicholas,” and handed me back the page to find my errors, waiting patiently behind my chair until I did.

One day I’d dropped my smudged assignment on the table and cried bitterly, “Of course it’s wrong! I always do it wrong!” He spun me around, slapped me hard, swung my chair to the table, and thrust the lesson book into my hands.

He’d said not a word. Blinking back tears I worked, my cheek smarting, until I got it right. After, he gave me another problem.

Now, in Forbee’s office, nobody was behind my chair, the

breath I’d felt but a wisp of breeze. I shivered, shook off my memories, and turned back to the holovid. “–do hereby resign my commission, effective immediately.” I put the point of the pencil to the screen to sign below the entry.

Time passed.

After a while the pencil fell from my fingers, rolled unheeded to the floor.

I couldn’t do it. I knew right from wrong; though Father wasn’t watching, he might as well have been. “ I, Nicholas Ewing Seafort, do swear upon my immortal soul to preserve and protect the Charter of the General Assembly of the United Nations, to give loyalty and obedience for the term of my enlistment to the Naval Service of the United Nations, and to obey all its lawful orders and regulations, so help me Lord God Almighty.”I’d administered the selfsame oath to Paula Treadwell and to Derek Carr. I was prepared to hang them should they break their pledge. I could not violate it myself.

Still, for a brief moment, my resolution wavered. Was my self-respect worth risking Hiberniaand her crew? Was even my immortal soul worth that? In the distance, Father waited for my reply. I will–he’d made me promise–let them destroy me before I swear to an oath I will not fulfill. My oath is all that I am.

I covered my face, ashamed of my tears. When I’d brought myself under control I put down my dampened arm, blinked in the sudden light.

I erased the entry. Captain Forbee sat motionless.

“I’m sorry. Very sorry.”

He nodded as if he understood.

“We won’t speak of it again.” My embarrassment was painful, but no more than I deserved. “I’m going back to my ship. Carry on victualing and off-loading. Report only if it’s necessary.” I stood.

“Aye aye, sir.” He got to his feet when I did. “If there’s anything I can do to help... “

“I need experienced officers. I don’t care where you get them. Find me at least two more lieutenants.”

“Aye aye, sir.” As I left the room he picked up his caller.

“Get a shuttle ready for the Commander at Admiralty House.”

Two hours later I strode through the mated airlocks onto Hibernia.Vax Holser, waiting at the hatch, fell into step beside me. “Are you all right, sir?” His manner was anxious.

“Did they accept your report?”

“I’m fine.” I started up the ladder to Level 1.

“Will they call a court of inquiry?”

“No.”

“Do you know who’ll replace you, sir?”

Why did he insist on goading me? “Mr. Holser, your duties are elsewhere. Get out from underfoot and stay out!”

Vax stopped short, shock and hurt evident. “Aye aye, sir.”

Quickly he turned away. I strode onto the bridge. Dejected, I slumped in my armchair. Vax had been worried for me, but I’d turned on him with savage anger. Would I ever learn? How often could I lash out without turning him back into a cold, unfeeling bully? The crew’s leave roster, prepared by the Chief, awaited my approval. I signed it. During Hiberniansmandatory thirtyday layover on Hope Nation the entire crew would be shuttled groundside, except for a few maintenance personnel whose shifts were rotated to provide the maximum leave. At least one officer would remain on board at all times, although he wasn’t required to stand watch.

By now all the passengers had disembarked, even those who were going on to Detour.

“Mr. Tamarov to the bridge.” I replaced the caller and waited. A few moments later Alexi appeared. “You’re on duty rotation the third week,” I told him. “That means you have two weeks off starting today, and another week at the end.”

“Aye aye, sir!” His eyes sparkled with excitement and anticipation.

“Just one thing.” His grin vanished. “As senior middy, you’re in charge of the cadets. I’m not holding them aboard the ship and we can’t turn Ricky and Paula loose in a strange colony unsupervised. Take them with you and keep an eye on them.”

“Aye aye, sir.”

He looked so crestfallen I offered a little cheer. “I didn’t mean at every minute, Alexi. You can still go out on the town. Either take them with you or bunk them down before you go. Just bring them back to the ship unharmed.”

He brightened. “Aye aye, sir. When are you going down, sir?”

“Tomorrow.”

“Will I see you before you’re transferred out?” A natural assumption; a new Captain wouldn’t want his predecessor looking over his shoulder. I’d have been reassigned to another ship until the next interstellar vessel arrived.

“You’ll see me,” I growled, suddenly anxious to be rid of him. “Dismissed.”

I sat in my leather armchair on the silent bridge. Eventually, I realized there was no reason to stay. I wandered down to

Level 2, where parties of sailors clustered around the airlock, laughing and joking, awaiting dismissal. To avoid passing them I went back up the ladder. I strolled past the wardroom, past Vax’s cabin, formerly Ms. Dagalow’s. I stopped in front of Lieutenant Malstrom’s quarters. For a moment I had an urge to go in and set up the chessboard.

My friend floated forever in empty space, while I had reached safe haven in Hope Nation. I recalled our mutual plans and promises. The drink I would buy him, the trip we would take to the Venture Mountains. My eyes stung. I resolved to do those things for him. I would take a shuttle groundside in the morning. I’d go into the first bar I saw and order an asteroid on the rocks. Then I’d check on transportation and arrange a trip across the sea to the Venturas.

On the way back to my cabin I realized how lonely my leave would be. I hesitated for a moment, swore under my breath, turned back to the wardroom. I knocked.

Ricky opened, stiffening to attention.

“Carry on, all of you.”

He and Paula Treadwell were packing their duffels, clothing strewn across their beds. Derek Carr, his duffel ready, sat on his bunk waiting for the call to the shuttle.

“Mr. Carr, a word with you, please.” I took him out to the corridor. He listened, obedient but aloof. “I thought-that is, I’m going on a journey, uh, for sentimental reasons.

To the Venture Mountains. Someone was going to take me there once.” Once more I hesitated, afraid to open myself.

“I thought perhaps you might like to come along as my guest.”

“Thank you, Captain,” he said, his voice cool. “I have other plans. I’m visiting my father’s plantations, and then I’ll see Centraltown. My regrets, sir.” I heard the message behind his words. Derek could take anything he set his mind to, as he’d proven, but that didn’t mean he would forgive me for the undeserved humiliation of the barrel the day I’d lost my temper. I’d never be pardoned for that, not by a boy with his pride.

“Very well, Mr. Carr. Enjoy yourself.” I turned away.

“Thank you, Captain,” he said to my retreating back. He added, “You too.” It made me feel a little better.

Early the next morning, Hiberniabore an eerie resemblance to the wreck of Celestina.Lights gleamed in deserted corridors. No sound broke the stillness. Somewhere on board–probably in his cabin–was the Chief, serving the first week’s rotation, but most of the crew had departed, except a galley hand and a few maintenance ratings.

I shouldered my duffel and crossed through the airlocks, strode along the busy corridors of the station to the Commandant’s small office.

“May I help you, sir?” A corporal looked up from his puter.

“I’d like a shuttle groundside.”

“Yes, sir. Just a moment, please.” Within moments I was ushered into General Tho’s office. He was distinctly more cordial than on my prior visit.

“You might as well wait here, Captain, while the shuttle is prepped. Coffee?” I joined him for a cup and chatted until the craft was ready. As I left he said, “If there’s anything further I can do, let me know.” His manner suggested we were senior officers exchanging courtesies. I supposed we were.

The shuttle was much larger than the one on which I’d first gone ashore, but I was the only passenger; apparently the small launch wasn’t available and General Tho had decided not to make me wait. I had a different pilot, less interested in conversation.

Groundside once more, I inhaled several lungsful of clean

fresh air under the bright morning sun. The temperature was warm and pleasant; at this latitude Hope Nation had long summers and mild winters at sea level. One of Hope Nation’s two moons was dimly visible overhead. It appeared slightly

larger than did Luna from Earth’s surface.

I decided not to check in with Admiralty House. If Forbee had any news he’d have called. If I showed up now, he would dump onto me decisions he could make himself. I went directly to the terminal building and out the other side, as I’d been directed earlier by the quarantine nurse.

A giant screen anchored to a metal pole greeted me. “Welcome to Centraltown, Population 89,267.” I watched for a few moments, wondering how often the number changed.

According to the guidebook the screen was tied directly to the puters at Centraltown Hospital; each birth and death were reflected within moments on the welcome sign. Centraltown was the largest, and virtually the only, city on Hope Nation; the remainder of the colony’s two hundred thousand population was spread among several small towns and the many outlying plantations that justified the colony’s existence.

I had imagined raw dirt roads, fresh cuts in the hills, ramshackle buildings set around a primitive main street. Disappointed, I had to remind myself that Hope Nation was opened back in 2081, over a century past. Since then, a massive influx of materials and settlers had been absorbed.

The roads were paved and modern, and seemed clean compared to the crowded and filthy streets of Earth’s great cities.

I peered down the main avenue. Clusters of buildings lined the street south toward Centraltown, but a few blocks in the other direction the road disappeared into hills rife with uncultivated vegetation.

I spotted the car rental agency at the end of the terminal building. In no particular hurry I sauntered to the entry.

“Knock loud and come in,” read the sign tacked to the door.

Inside, a tiny waiting room, with a counter. I banged on the desk.

A young woman popped from behind a curtain leading to the back. “Hi, you must be from Hibernia.”She seemed about twenty. Long brown hair flowed unhindered to her shoulders.

I set down my duffel. “Yes, I am.”

“Looking for a car, huh?”

“That was the idea.” I studied her. If she was a typical Hopian, business here was conducted far more casually than at home.

“I think maybe we’ll have one later.” A shrug. “Yesterday the sailors grabbed all I had. One’s due back this afternoon.”

She shot me a dubious look. “You have to be twenty-one to rent. Age of majority. You don’t look that old.”

“I’m a Naval officer.” I pulled out my ID, which still showed me as a midshipman. I’d have to get that changed.

“I have my majority.”

“I guess,” she said vaguely. “Come back sometime this afternoon; I’ll see if one’s in yet.”

“Will you make a reservation for me?”

“You mean, hold a car? Sure. What’s your name?”

“Nick Seafort.”

“Right. If I’m not here, ask for me at the restaurant inside.”

“What’s your name?”

“Darla.” I started. She asked, “What’s the matter?”

“Nothing. I knew a girl named Darla once.”

That brought a smile. “Was she nice?”

“I liked her. Sometimes when she made her mind up it was hard getting her to change it.”

“Oh, well, I’m not like that.” It could have been an invitation.

“What can someone do on foot around here?”

“There’s the terminal restaurant. If you want drinks, the Runway Saloon’s just up the block. Just don’t order doubles.”

“Right. Thanks.” I wandered out. The bar reminded me of my promise to Lieutenant Malstrom: a drink at the first bar we came to. I sighed. It was absurd to drink so early in the day, but I could think of nothing better to do, and a promise was a promise. I strolled along the street past the edge of the field, until I came upon a battered building with sheet-metal siding.

“Permanent Happy Hour!” the sign read. “All drinks always half price!” If drinks were always half price, what were they half of? I shrugged.

Inside, the bar smelled of stale alcohol and fried food. The light show bounced patterns off the walls in time to thumping electronic music, making it hard for me to see. A babble of voices indicated that people were in the back of the room.