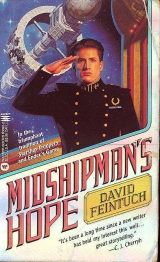

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

It was the Naval solution, of course. A confrontation like ours was intolerable, so we wouldn’t allow it to happen. We wouldn’t recognize its existence, just as a Captain would be blind to a midshipman’s black eye. My apology would satisfy his pride, but would have no other effect; I’d be putting it on a record that was to be destroyed.

He glowered. “You goddamn wiseass.”

I ignored the blasphemy. “You tried a fancy move and it didn’t work,” I said. “If I’d handed her over, you’d have kept her past the time I sailed and the issue would be moot.

As it is, I win. Why’d you go out on a limb for the Treadwells? They’re not even locals.”

The Judge pulled out his chair and slumped into it. “Their lawyer,” he muttered. “Miss Kazai. She’s helped me out.”

“Well, she’ll know you tried.” Having won, I could afford to be conciliatory.

He gave me a small, grim smile. “Never come back to Hope Nation as a civilian. Not while I live.”

My triumph vanished. I thought of Amanda. “No,” I said.

“I won’t be back.”

We returned to the courtroom and went through our charade. I apologized humbly for my unmannerly remarks. The judge erased the record. He then looked through the file and dismissed the Treadwells’ petition for lack of jurisdiction.

Mrs. Treadwell jumped to her feet as I passed her on the way out. “You won’t get away with it!” she shouted. “The courts in Detour will help us! We’ll see you there!”

I shrugged. Perhaps.

26

Though the hearing was officially suppressed, the story made its way through the ship. Vax wore a foolish grin for the rest of the day, even during his watch. Alexi went so far as to congratulate me openly; I bit back a sharp reproof.

The rest of our crew straggled back from shore leave. Our final passengers were ferried up to the ship and settled in thencabins. Among the last to board were the Treadwells. I had them escorted directly to the bridge.

“I thought of refusing you passage,” I told them. “But I don’t want to separate Rafe and Paula sooner than necessary.

I let you aboard, but one more protest, one petition, a single interference with the operation of my ship–and that includes harassing Paula–and you’ll spend the entire trip in the brig.

Is that understood?”

It wasn’t that easy. I had to threaten to have them expelled to the station before they finally gave me their agreement.

The purser’s last-minute stores were boarded. A new ship’s launch, replacing the ill-fated one on which our officers perished, was safely berthed by Lieutenant Holser under my anxious scrutiny. Darla recalculated her base mass without comment.

To my relief all our crew members returned from shore leave; we had no deserters, no AWOLs. Seventeen passengers for Detour chose not to continue their trip; that didn’t bother me. Others took their places. On this leg, we would cany ninety-five passengers.

Derek paged me fromhis duty station at the aft airlock.

“The new midshipman is at the lock, reporting for duty, sir.”

“Very well. Send him to the bridge.” Suddenly I was back at Earthport Station, smoothing my hair, nervously clutching my duffel, anxious to make a good first impression when I reported to Captain Haag. Now I was at the other end of the interview.

“Permission to enter bridge, sir.” An unfamiliar voice.

“Granted,” I said without turning.

“Midshipman Philip Tyre reporting, sir.” He came to attention smartly, his duffel at his feet.

I turned to him and fell silent. He wasn’t handsome–he was beautiful. Smooth unblemished skin, wavy blond hair, blue eyes, a finely chiseled intelligent face. He could have been lifted from a recruiting poster.

I took his papers, letting him wait at attention while I looked them over. He’d joined at thirteen and now had three years service. That put him senior not only to Derek, but to Alexi as well. A disappointment for Alexi, but that couldn’t be helped. I had plans for Alexi soon enough.

“Stand easy, Mr. Tyre.”

“Thank you, sir.” His voice was steady and vibrant.

“Welcome to Hibernia.”I stopped myself from offering my hand. The Captain must keep his distance. “You’ve been on interplanetary service for the past year?”

The boy flashed a charming smile. “Yes, sir.”

“And you’ve been to Detour.”

“Yes, sir. On Hindenberg,before I was transferred out.”

Tyre had seen a lot of service, more than I had when I’d been posted in Hibernia.“It seems you’re to be senior middy.”

“That’s what I understood from Captain Forbee, sir.” His smile was pleasant. “I think I can handle it.”

“Good. Mr. Tamarov was senior for a while, but I doubt he’ll give you any trouble.”

“I’m sure he won’t, sir.” Was there more emphasis in his tone than necessary? “Very well, Mr. Tyre. Get yourself settled in the wardroom, and have a look around the ship.”

“Aye aye, sir.” He saluted and picked up his duffel with graceful ease. ‘“Thank you, sir.” He turned and marched out.

I made a note to reassure Alexi that he hadn’t been intentionally demoted.

I sat back, comparing the new middy’s entry to Mr.

Chantir’s. Our new lieutenant had come aboard the evening before. He’d reported to the bridge, saluting easily. He responded to my welcome with a warm, friendly grin. “Thank you, sir. It’s good to be aboard.”

“It says here you have special talent in navigation.”

“I wouldn’t say special, sir,” he said modestly. “But I enjoy solving plotting problems.”

“Then I’ll put you in charge of the midshipmen’s drills.”

He smiled again. “Good. I love to teach.” I knew immediately that I would like him. I thought of embittered, tyrannical Lieutenant Cousins and how I’d dreaded our lessons.

We were ready to depart. The Pilot at the conn, we cast off, maneuvered a safe distance from the station, and Fused almost at once. I was so busy I forgot to watch Hope Nation dwindle on the screens before they blanked.

It wouldn’t be long before the stars reappeared; we were on a short run to Bauxite to pick up our third lieutenant. A voyage of five weeks by conventional power, in Fusion we could make the hop in less than a day. We’d take longer to maneuver the ship for mating with U.N.S. Breziathan to travel the interplanetary distance in Fusion.

Breziawas a small cruiser that shuttled back and forth among the planets of Hope Nation system, available for orbital rescues or other needs of the civilian mining fleet and the area’s commercial craft. Lacking fusion engines, Breziacruised at subluminous speeds. Unfortunately, her Captain was only rated interplanetary or I would have shanghaied him as well as his lieutenant.

Pilot Haynes and Lars Chantir worked together during the docking. The Pilot, true to his word, gave no trouble. As he’d said, he was good at his job. After we located Breziahe deftly maneuvered us into matching velocity. To avoid the cumbersome chore of mating airlocks, we drifted to within a hundred meters of Breziaand I had a T-suited sailor carry a flexible line to their lock. Shortly after, our new officer came across the line, hand over hand, his duffel tied behind his suit.

Having little else to do, I went to the lock to meet him.

Correctly, he stripped off his suit before coming to attention.

“Lieutenant Ardwell C. Crossburn reporting, sir.” A short, round-figured man in his late thirties.

“Stand easy, Lieutenant. Welcome aboard.”

“Thank you, sir.” He looked around at his new ship. “As soon as I get my gear stowed I can take up my duties, sir.

I’ll try to be of assistance.”

“No hurry, Mr. Crossburn,” I said in good humor. “You can wait until after dinner.”

“Very well, sir. If you insist.” An odd way to speak, but the man had a peculiar manner about him. Well, his record showed him to be a competent and experienced officer. I returned to the bridge and waited impatiently while Mr.

Haynes and Lieutenant Chantir plotted Fusion coordinates and rechecked them together. Laboriously I went through the calculations myself and found no error. We Fused.

In seven weeks we would reach Detour, a younger colony than Hope Nation, and one whose environment was less hospitable to humankind. Its air held less nitrogen and slightly more oxygen, but it was breathable. They’d had to do a lot of terraforming to bring down the sulphuric compounds in the atmosphere before Detour could be developed. Now the planet was open for colonization and some sixty thousand settlers had already arrived.

Lars Chantir was my senior lieutenant. Mr. Crossburn, with six years experience, was second. Vax was last in line, but that mattered less among lieutenants than midshipmen, unless the Captain died. The barrel was duly moved to First Lieutenant Chantir’s quarters; it was a traditional duty of the senior lieutenant.

I had time on my hands, time to miss Amanda. Our nights in the hills of Western Continent had provided the first sustained intimacy I’d ever known. Knowing how incapable I was, Amanda had still cared for me. I yearned for her presence.

We settled down to shipboard routine. I missed the familiar passengers: Mrs. Donhauser, Mr. Ibn Saud, and, of course, Amanda. Few of our original group were continuing with us; unfortunately the Treadwells were among them.

One day Vax came to me on the bridge, troubled. “Sir, there’s something I think you should know.”

“What’s that?”

He hesitated, on difficult ground. “Lieutenant Crossburn, sir. He’s been questioning the crew about the attack at Miningcamp. At first I thought he was just making conversation, but he’s seeking out the men who were most involved.”

I chose the easy way out. “You know better than to complain about a superior officer.”

“Yes, sir. It wasn’t a complaint. I was informing you.”

“Drop it. I don’t care what he asks.” I had nothing to hide from my new lieutenant. My conduct would be subject to Admiralty’s unblinking scrutiny as soon as we reached home, and I knew I had no chance of emerging without substantial demotion, if not worse. Mr. Crossburn’s inquiry could do no harm to my shattered career, though it was unusual.

More disturbing was Lieutenant Chantir’s casual comment while I perused a chess manual on a quiet watch. “I’m surprised your midshipmen don’t make more effort to work off demerits, sir.”

“What do you mean?”

“Yesterday I caned one of them for reaching ten. You’d think he’d take the trouble to exercise them off. They’re only two hours apiece.”

“Which midshipman?” I asked, my mind on the queen’s gambit.

“Mr. Carr. I rather let him have it, for his laziness. What is your policy, Captain? Should I go hard or easy?”

“Neither,” I said, disturbed. “Use your judgment.” I had issued Derek seven demerits for trying to choke me–and I hadn’t forgotten to log them when we got back–but he would have been too well trained by now to blunder into more.

“How many did he have?”

“Eleven.” Very odd. I didn’t think Derek would step that far out of line.

“Let’s look them up.” I turned on the Log, suspecting I knew the answer. If a lieutenant wanted Derek caned he didn’t have to trouble giving him demerits, he would merely send him to Mr. Chantir with orders to be put over the barrel. A first midshipman, on the other hand, couldn’t issue such an order. He could only assign demerits, which if given fast enough would have the same effect.

I flipped through the daily notations made by each watch officer. “Mr. Carr, improper storage of gear, one demerit,by Mr. Tyre.... Mr. Carr, insubordination, two demerits,by Mr. Tyre.”Why hadn’t Derek worked them off? I turned the pages. “Mr. Carr, improper uniform, two demerits, byMr. Tyre.... Mr. Carr, inattention to duty, two demerits,by Mr. Tyre.”There it was. Tyre was piling demerits on Derek faster than he could exercise them off.

I decided I couldn’t interfere. It was Derek’s bad luck Tyre had made an example of him; the new first middy was asserting his authority. But though I put the incident out of my mind, I had been a midshipman too recently to miss the other signs of trouble. When I saw Alexi on watch he seemed more hesitant, more preoccupied. More significant, I never saw him off watch except at dinner. I realized all my midshipmen seemed to have dropped out of sight. I hoped Alexi would give me a hint, but he was too Navy to do that.

Wardroom affairs were settled in the wardroom.

It was not a busy time for me. In Fusion, we had no need for navigation checks, no data on the screens, nothing to do except keep an eye on the environmental systems: recycling, hydroponics, power. Brooding about the wardroom situation, I began watching for new Log entries.

Derek, Alexi, and both cadets were fast accumulating demerits. Seven for Alexi in three days, two more for Derek.

Sixteen between Paula and Ricky.

I bent the rules to ask Philip Tyre outright. “Everything going well in the wardroom, Mr. Tyre?”

He smiled easily. “Yes, sir. I have it under control.” As always, he was immaculate. Slim and slight, his face was faintly disturbing in its perfection.

“You’re working with a good group of officers, Mr.

Tyre.”

“Yes, sir. They need reminding who’s in charge, but I’m on top of that.” His innocent blue eyes questioned me. “Is anything wrong, sir?”

“No, nothing,” I said quickly, knowing I had strayed across the unwritten line that kept the Captain out of the wardroom’s business.

Dr. Uburu came to me next, catching me outside the dining hall on the way back from dinner. “Did you know,” she asked gravely, “that I treated Paula Treadwell this week?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“I thought not.” She paused as we reached the top of the ladder.

“What for, Doctor? If I’m not violating your professional ethics?”

“Hysteria.” She met my eye.

“Good Lord.” I waited for her to continue. She said nothing.”What was the cause?”

“I swore an oath not to tell you,” she said. “My patient insisted, before she’d talk about it.”

My hand clenched the rail. “I could order you,” I said.

“Yes, but I wouldn’t obey.” Her voice was calm. She smiled, her dark face lighting with warmth. “I don’t mean to make problems, Captain. Just keeping you advised.”

“Thank you.” I went to my cabin and lay on my bunk, wishing the Chief still visited for evening conversations.

Since I’d broken off our sessions after Sandy’s death he had been friendly and helpful, but had kept his distance.

My next watch was shared with Lieutenant Crossburn.

After a long period of silence he made efforts to start a conversation. I let him lead it, my mind elsewhere. He soon brought up the attack at Miningcamp. “When the rebels forced their way on board,” he asked,”who was most helpful in repelling them?”

“Mr. Vishinsky was invaluable,” I said, not wanting to be bothered. “And Vax Holser.”

His next question snapped me awake. “What made you decide to let a dozen suited men on board in the first place?”

My tone was sharp. “Are you interrogating me, Lieutenant”?”

“Not at all. But it was an amazing incident, Captain. I write a diary. I try to include important things that happen near me. I’ll change the subject if you’d rather.”

“No,” I said grudgingly. “It was a mistake, letting them on board. I very much regret it.”

He seemed pleased at my confidence. “It must have been a terrible day.”

“Yes.”

“I write every evening,” he confided.”I pour my thoughts and feelings into my diary.”

“It must be a great solace,” I said, disliking him.

“I never show it to anybody, of course, even though it reads quite well. I’m the only one who’s seen it, other than my uncle.”

It seemed polite to prompt him. “He’s a literary critic?”

“No, but he understands Naval matters. Perhaps you’ve heard of him. Admiral Brentley.”

Heard of him? Admiral Brentley ran Fleet Ops at Lunapolis, and this man had his ear! My heart sank.

“You’ve written about Miningcamp in that little diary, Lieutenant?”

“Oh, yes.” His manner was modest. “It’s very dramatic.

Uncle will be intrigued, I’m sure.”

I let the conversation lapse, fretting. After a while I shrugged. Admiralty didn’t need Mr. Crossburn’s little book to know how badly I’d managed.

But three weeks into the cruise I knew I would have to take action. Mr. Crossburn had left the subject of Miningcamp and was asking about the execution of sailors Tuak and Rogoff. At the same time, the morale of my midshipmen and cadets was plummeting. Alexi stalked the ship in a cold fury, civil to me but otherwise seething with unexpressed rage. Derek appeared depressed and tired.

“I’ve had Mr. Tamarov up twice,” Lieutenant Chantir told me. “I went fairly easy on him, but I had to give him something.” I was already aware; I was watching the Log carefully now. I began checking the exercise room, realizing that one of the reasons I rarely saw the middies and cadets was that they were usually working off demerits.

Perplexed, I took my problems to Chief McAndrews. At this point I didn’t hesitate to display my ignorance. He already knew my limitations.

“What did you expect?” he asked bluntly. “You asked the Naval station to supply you officers. Where did you think they’d get them?”

“I don’t understand.” I shuffled, feeling young and foolish, but I needed to know.

He sighed. “Captain, Mr. Chantir volunteered, yes? The other two officers were requisitioned. If Admiralty told you to supply a lieutenant for an incoming ship, whom would you pick?”

“Mr. Crossburn.” I spoke without hesitation.

“And which midshipman?”

I swore slowly and with feeling.

“You gave the joeys in the interplanetary fleet a chance to get rid of their worst headaches.”

I damned my stupidity, my blindness. “How could I have been so dumb? I asked for officers and didn’t even check their files to see who I was getting!” A real Captain would have Blown to watch for that trick.

“Easy, sir. What do you think the files would have shown?”

I paused. A good question. The notation “tyrant” or “sadist” was unlikely to appear in Mr. Tyre’s personnel file. As for Lieutenant Crossburn’s diary, what the man wrote in his cabin during his free time wasn’t subject to Naval regulations.

Even if his officious private inquiries stirred up trouble, that was hard to prove, and moreover it would be foolhardy to rebuke a man who had the ear of the fleet commander. No wonder his Captain was delighted to get rid of him.

I went back to my cabin to think. I had no sympathy for those who misused our Naval traditions for their own ends, but I didn’t know how to stop Mr. Tyre without violating tradition myself. As for Mr. Crossburn, how could I order him not to keep a diary? I found no solution.

In the meantime, I ordered Alexi to advanced navigational training, followed by a tour in the engine room under Mr.

Me Andrews. That should give him some respite from Mr.

Tyre.

It didn’t. Alexi continued to accumulate demerits. Again he reached ten and was sent to Lieutenant Chantir’s cabin.

Two days later we shared a watch. He eased himself into his chair, wincing. I blurted, “Be patient, Alexi.”

“About what, sir?” His voice was unsteady. Seventeen now, nearly eighteen, he could expect better treatment than he was getting. Yet his Academy training held firm. He would not complain to the Captain about his superior.

I deliberately stepped over the line. “Be patient. I know what’s going on.”

He looked at me, his usual friendliness replaced by indifference. “Sometimes I hate the Navy, sir.”

“And me too?”

After a moment his face softened. “No, sir. Not you.” He added quietly, “A lot of people are being hurt.” It was as close as he would come to discussing the wardroom.

Meanwhile Mr. Crossburn continued his scribbling. On watch he would flip idly through the Log, scrutinizing entries made prior to his arrival. He was delving into Alexi’s defense of the unfortunate seamen at their court-martial. He asked me how well I thought Alexi had performed.

“Lieutenant, your questions and the reports you write are damaging the morale of the ship. I wish you’d stop.”

“Is that an order, sir?” His tone was polite.

“A request.”

“With all due respect, sir, I don’t think my diary is under Naval jurisdiction. I’ll ask Uncle Ted about that when I see him. As for asking questions, of course I’ll stop if you order it.”“Very well, then, I so order.”

“Aye aye, sir. Since your order is so unusual I request that

you put it in writing.”

I considered a moment. “Never mind. You’re free to carry on.” A written order, viewed without knowledge of his constant prying, would appear paranoid and dictatorial. Anyone who hadn’t experienced Lieutenant Crossburn firsthand wouldn’t understand, and I was in enough trouble with Admiralty as it was.

I had little better luck with Philip Tyre. I called him to my cabin, where our discussion could be less formal than on the bridge.

“I’ve been reviewing the Log, Mr. Tyre. Why do you find it necessary to hand out so many demerits?”

He sat at my long table, his arm resting on the tabletop much as the Chief’s had before I’d isolated myself. His innocent blue eyes questioned me. “I’ll obey your orders, sir.

Are you telling me to ignore obvious infractions?”

“No, I’m not. But are you finding infractions, or searching for them?”

“Captain, I’m doing the best I know how. I thought my job was to keep wardroom affairs from coming to your attention, and I’ve been trying to do that. As I certainly haven’t called any problems to your notice, someone else must have.” It was said so reasonably, so openly, that I could have no complaint.

“No one’s complained,” I growled. “But you’re handing out demerits faster than they can work them off.”

“Yes, sir, I’ve noticed that. I encouraged Mr. Carr and Mr. Fuentes to spend more time in the exercise room. I’ve even gone myself to help them with their exercises. A better solution would be for them to stop earning demerits.” His untroubled eyes met mine.

“How do you propose that they do that?”

“By following regulations, sir. My predecessor must have been terribly lax. I observe a lack of standards in his own behavior, sir. It’s no wonder he couldn’t teach the others. I’m trying to deal with it.”

I sighed. The boy was unreachable. “I won’t tell you how to run the wardroom. I will tell you that I’m displeased about the effects on morale.”

Tyre’s voice was earnest. “Thank you for bringing it to my attention, sir. I’ll make sure their morale problems don’t bother you further.” “I want them eliminated, not hidden! That’s all!”

The midshipman saluted smartly and left. I paced the cabin, bile in my throat. Very well; he’d been warned. I would give him until we left Detour. If he didn’t improve, Mr. Tyre had made his bed; he’d have to sleep in it.

On my next visit to the exercise room I found Derek and Ricky working, Derek on the bars, the cadet struggling at push-ups and leg lifts on the mat. Alexi was absent. The two perspiring boys waited silently for me to leave.

I didn’t come across Alexi for three days, until we next shared a watch. “You haven’t been in the exercise room of late, Mr. Tamarov.”

He glanced at me without expression. “No, sir. I’ve been confined to quarters except to stand watch and go to the dining hall.”

“Good Lord! For how long?”

“Until my attitude improves, sir.” His gaze revealed nothing, but his cheeks reddened.

“Will it improve. Alexi?”

“Unlikely, sir. I’m told I’m not suitable material for the Navy. I’m beginning to believe it.”

“You’re suitable.” I tried to cheer him up. “This will pass. On my first posting my senior middy was very difficult to deal with, but we got to be friends.” I realized how fatuous I sounded. Jethro Hager was nothing like the vicious boy fate had put in charge of my midshipmen.

“Yes, sir. I don’t mind so much, except when Ricky cries himself to sleep.”

I was alarmed. “Ricky, crying?”

“Only two or three times, sir. When Mr. Tyre isn’t around.” That was bad. Ricky Fuentes was a cheerful, goodnatured boy; if he was in tears something was very wrong. I thought briefly of the lesson I had given Vax Holser when I succeeded to Captain, an approach I’d decided against with our new midshipman. In Vax’s case I’d recently been a member of the wardroom and had personal knowledge of his behavior. Also, Vax was a good officer who was making a sincere effort to combat a personal problem. Philip Tyre was not.In three weeks we would Defuse for a nav check, and then we’d have only a few more days to Detour. I could wait.

But a few days later Mr. Chantir raised the subject openly.

“Sir, something’s gone wrong in the wardroom. I’ve had Mr.

Carr and Mr. Fuentes up again. The Log is littered with demerits.”

“I know.”

“Is there anything you could do?”

“What do you suggest, Mr. Chantir?”

“Remove the first midshipman, or distract him. Lord, I’d enjoy having him sent to me with demerits after what he’s done to the others.”

“He’ll make sadists of us all, Mr. Chantir. No, I won’t remove him. I have witnessed no objectionable behavior.

He’s scrupulously polite, he obeys my orders to the letter, he’s excellent at navigation drills and in his other studies. I can’t beach him simply because I don’t like him.”

“That wouldn’t be the reason, Captain.”

“No, but that’s what it would look like to Admiralty. They don’t know that Derek and Alexi aren’t giving him a hard time.”

“What do you expect of me when these joeys are sent to the barrel, then?”

“I expect you to do your duty, Mr. Chantir.” He quickly dropped the subject.

As time passed Mr. Crossburn threw caution to the winds.

Twice he mentioned how eagerly he was looking forward to seeing his uncle Admiral Brentley and talking over old times.

I ignored him, but my uneasiness grew.

For a diversion I called drills. The crew practiced Battle Stations, General Quarters, Fire in the Forward Hold at unexpected intervals. The sudden action seemed a relief.

At last came the day Pilot Haynes took his place on the bridge, along with Alexi and Lieutenant Chantir. I brought the ship out of Fusion, and stars leaped onto the simulscreens with breathtaking clarity. The swollen sun of Detour system glowed in the distance. We would Fuse for four more days

and emerge, hopefully, just outside the planet’s orbit.

I waited impatiently for the navigation checks to be done.

With Pilot Haynes, Mr. Chantir, and Alexi all computing our course there was no need for me to recheck their calculations, but still I did. Finally satisfied, I ordered the engine room to Fuse.

That evening, I had a knock on my cabin hatch. Philip Tyre stood easily at attention, his soft lips turned upward in a pleasant expression. “Sir, excuse me for intruding, but a passenger wishes to speak to you. Mr. Treadwell.” A passenger couldn’t approach officers’ country; he needed an escort to arrange contact with me unless he found me in the dining hall.”Tell him to write–oh, very well.” Though I could refuse to see him, another tirade from Jared Treadwell about his daughter was no more than I deserved for rashly enlisting her.

“Bring him.” The middy saluted, spun on his heel, and marched off. I paced in growing irritation, dreading the interview.

Again, a knock. “Come in,” I snapped. Mr. Tyre stepped aside. Rafe Treadwell came hesitantly into my cabin. I blurted, “Oh, you. I was expecting... “ I waved Philip his dismissal.

The lanky thirteen-year-old smiled politely. “Thank you for seeing me. sir.”

“You’re welcome. Is this about your sister?”

“No, sir.”

I waited. He stood formally, arms at his sides. “I’m hoping, Captain Seafort, that you’d allow me to enlist too.”

For a moment I was speechless. “What?” I managed. “Do what?”

“Enlist, sir. As a cadet.” Seeing my expression he hurried on. “I thought I wanted to stay with my parents, but things have changed. I don’t know if you need more midshipmen but I’d like to volunteer. I’d like to be with my sister for a while longer, and I just can’t believe how much the Navy has done for her.”

I shot him a suspicious look. If the boy was twitting me I’d stretch him over the barrel, civilian or no.

“I mean it, sir. She always used to ask me for help. Now she doesn’t even have time for me and when I do see her, it’s like talking to a grown-up. She’s about three years older than me now.” He shook his head in wonderment.

“What about your parents?”

“Paula and I were creche-raised, sir. Community creche, back in Arkansas. I knew our parents but we didn’t spend much time with them. They took us out of creche when they decided to emigrate. They can survive without us.”

“They don’t act like it.”

He grinned. “They think togetherness is something they can proclaim. They don’t realize you have to grow up with it. They’ll get used to being without us.”

“And the discipline? You’d enjoy that?”

“No, I’ll probably hate it. But it might be good for me.”

He sounded nonchalant, but, at his side, his hand beat a tattoo against his leg.

I paced anew. Another midshipman would be useful, though hardly necessary. Having Rare in the wardroom would certainly help Paula’s morale. But taking both Treadwell children without their parents’ consent wouldn’t be appreciated by Admiralty at home, to say nothing of the Treadwells.

Well, I was already in so much hot water that one more mistake didn’t matter.

“I’ll let you know.” I opened the hatch.

“But I’ve only got–”

“Dismissed!” I waited.

“Yes, sir.” His tone was meek, passing my first test.

That night Mr. Tuak came, for the first time in months. He peered at me through the cabin bulkhead, making no effort to grab me, until at last I woke. I was disturbed, uneasy, but barely sweating. I showered and went back to sleep, unafraid.

Three days later we Defused for the last time on our outward journey. We powered our auxiliary engines for our approach to Detour. Pilot Haynes, Mr. Tyre, and Alexi had the watch; of course I was also on the bridge.

Philip Tyre sat stiffly at a console checking for encroachments. I noticed he kept Alexi on a very short leash, ordering him to sit straight when he relaxed in his seat and observing Alexi’s work closely. Tyre never raised his voice, never asked anything unreasonable, and never missed a thing.

Detour Station drifted larger in the simulscreens as the Pilot maneuvered us ever closer. Finally the rubber seals on the locks mated. We had arrived.

I thumbed the caller. “Mr. Holser, arrange a shuttle. I’ll be going planetside.”

“Aye aye, sir.”

I turned to Philip Tyre. “Where’s Mr. Carr?”