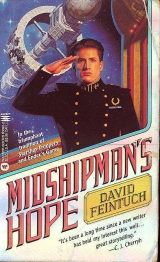

Текст книги "Midshipman's Hope"

Автор книги: Дэвид Файнток

Жанры:

Космическая фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

I waited for my eyes to accustom to the dark. It was the kind of bar where you stared moodily at the drink in your hand; just right for spacemen.

“What’ll you have?”

“Asteroid on the rocks.” An experienced bartender, he.

knew my uniform meant he could serve me without checking my age. There were very stiff penalties for serving minors, both for the bartender and the minor.

I took my drink and slid into a dimly lit booth to the side, tossing my jacket on the seat beside me. I took a sip and nearly choked. The alcohol tasted almost raw, and there was a lot of it. No wonder Darla had warned me about a double.

An asteroid on the rocks. Whiskey, mixed fruit juices, and Hobarth oils, imported from faraway Hobarth or imitated with synthetics. In this case, probably synthetics; I suspected the Runway Saloon didn’t stock imported liqueurs.

Actually the drink wasn’t bad, just strong. Silently I raised my glass to the empty seat across from me and saluted Harv Malstrom. It would have been great, Harv, to be sitting across from you. You’d make a joke about the drinks, and I’d grin, enjoying your company, recalling our most recent chess match. The alcohol made my eyes sting. I took another long swig. It burned going down. I had another swallow to ease my throat. After a time I sat tapping an empty glass, staring moodily at the empty seat, while flashing lights danced on the walls.

“Ready for another?”

“No.” I looked at my watch. Early yet. “I suppose. A small one.”

“Sure.” He grinned without mirth and handed me the glass he’d already brought. A comedian. He should have been on the holovid.

About halfway through the second drink I thought I’d feel better if I closed my eyes, and that was easier to do when my head was resting on the table. I stayed that way, drifting in and out of a doze, while the bar filled and the noise grew louder.

“Detour! Off to Detour for seven weeks, then another week’s leave.” A woman’s voice. Ms. Edwards, our gunner’s mate.

“You joes should work the Hope Nation system. You’re never more than five weeks from port. One easy run after another.” My eyes were open now but my head stayed on the table. I listened, drifting.

“Nah, who wants a milk run? You gotta go deep to get action.” Guffaws.

“Sure, joeygirl.” The voice was mocking. “It’d be great, stuck interstellar with a tyrant for a captain and only fourteen months to go!”

“Hey, don’t slam our Captain, buster!”

“Hah. I hear he’ll be out of diapers soon!”

“Listen, grode, I’d rather sail with Captain Kid that one of your system sissies who’d wet his pants if he couldn’t see a sun.” I blinked, focused on the empty glass.

“Captain KID? You spank him if he makes a mistake?” I felt my ears flame.

“Hey, Seafort’s all right! Sure, Captain Kid gets a wild hair up his ass sometimes–what officer don’t? But that joey knows what he’s doing. He took the puter apart singlehanded, ‘cause he knew she was planning to kill us. If he hadn’ta found her glitches we’d be half outta the galaxy heading for Andromeda.”

Another voice joined in. “I’ll match him mean for mean with any Captain in the fleet. Two joes we had, they beat up on the CPO. They were real garbage, druggies and worse, but always got away with it. He hanged them himself without batting an eye. And you know about Miningcamp, where they tried to seize our ship?”

Yes, tell them about my folly at Miningcamp. Sickened, I closed my eyes.

“Those scum shot their way aboard, the Captain held them off with a laser in each hand ‘til help came. When it was over he marched one of them right out the airlock and made him breathe space, and laughed all the way back to the bridge! He’s tough, Captain Kid is. You don’t mess with him. I’d rather be on a ship with him than with some old fart can’t find his way to the head!”

For some reason I was feeling better. Time to go, before they found me spying on them. Cautiously, I raised my head.

I was dizzy but functioning. I gathered my jacket, left a few unibucks on the table, and moved as quietly as I could to the door. Nobody saw me. I slipped outside, greedily sucking in the fresh air.

“God, it’s the Captain!” Two of Hibernia’sratings saluted hurriedly. I fumbled a return salute and kept moving, working at making my unsteady legs cooperate. I lugged my duffel toward the shuttleport, feeling a bit more steady with each step. By the terminal 1 was nearly myself again. I made for the rental agency at the far end.

“Hey, Captain, wait up!” I turned. Derek Carr in civilian garb, waved from the far end of the building. He ran to catch up. He stopped, his face flushed with healthy exertion. “Sir, 1, uh–” All at once, he looked abashed.

Impatient, I asked, “What, Derek?”

“Your invitation. Is it too late to accept?”

I studied his face, unsure of my answer.

He stared at the pavement. “Sorry about the way I spoke to you yesterday. I’m still immature sometimes. I’d enjoy touring with you, sir, if you’ll have me.” With an effort, he raised his head and looked me in the eye.

My smile was bleak. “What changed your mind, Derek?”

“I was steamed over your sending me to the Chief, even though I really was asking for it that day. Then I remembered two things: 1 promised you I could take anything, and you were the only person who was kind to me when I really needed it.” His face lit in a smile. “That was the most important thing anyone’s ever done for me. So holding a grudge is pretty stupid. I’m sorry, sir.”

I smiled back, meaning it this time. “What about your trip to your plantation?”

“I thought, sir, perhaps you’d like to come with me.” His smile vanished. “Though I’m not sure we’d be welcome.

My father told me that the manager, he... “He shrugged.

“Anyway, we could go to the mountains afterward.”

I debated, my melancholy lifting. His company would be more pleasant than my own. “Sounds great. I’ll rent a car.”

“I already have one, sir. I got it yesterday.” He blushed.

“I was sort of waiting until you came down.”

“Right.” I followed him to his electricar, a tiny threewheeler with permabatteries that could power the vehicle for months. I thought fast. “Derek, while we’re groundside, I want you to call me Mr. Seafort, as if I were first middy.

And you don’t have to say ‘sir’ all the time. Just make sure you switch back when we go aboard again.”

“Aye aye, si–I mean, thank you, Mr. Seafort.” We climbed in. I took off my jacket and tie and stowed my duffel in the back seat. “I’ve got a tent and supplies in the trunk,”

he said. “If you’re ready, I am. It’s a two-day drive.”

I leaned back and closed my eyes. “Wake me when we get there.”

A couple of hours out of Centraltown we came upon the Hope Nation I’d first expected. The three-lane road gave way to two lanes and then one and a half. Instead of pavement, only gravel. Homes were few and far between. Occasionally a cargo hauler lumbered toward Centraltown. We passed the time chatting and joking, sharing a merry mood.

Our route paralleled the seacoast a few miles inland. Occasionally, from a high point, we caught a glimpse of the shimmering ocean; more often our path cut through a dense jungle of viny trees of unfamiliar purplish hues.

We stopped for lunch at Haulers’ Rest, a comfort station and restaurant about two hours from the edge of the plantation zone. The public showers were in an outbuilding. After, we walked past enclosures of turkeys, chickens, and pigs to the restaurant entrance. Cargo haulers were parked at random in the mud-packed parking lot.

Haulers’ Rest generated its own electricity from a small pile in the back pasture, pumped water from deep wells, and prepared most of its own food from the hoof. Wheat and corn fields provided the grains, from hybrid stock that needed no pollination. On Hope Nation, no local blights affected our terrestrial crops, and there were no insects to harass the livestock, so everything grew fast and healthy.

After a stomach-stretching meal (ham steak, corn, green beans, homemade bread, lots of milk) we waddled to the car to resume our trip.

During the afternoon we pulled aside frequently to take in the rugged view. The forest was strangely silent. No birds circled above; no animals called out their cries. Only the soft wind that rippled through the incredibly dense vegetation.

The land wasn’t fenced, but each plantation had its own identifying mark nailed to trees and posts along the road, much like the brands once put on cattle. The first we came to stretched many miles before it gave way to another.

As evening settled, rich reds dominated the sky, fading to subtle lavender. The two moons, Major and Minor, sailed serenely over scattered clouds. By now we both were tired, and I began watching for markers along the road. I said, “Let’s pick a plantation before it gets too late.”

According to the holovid guides, Hope Nation had few inns outside Centraltown, so plantations provided free food and lodging to travelers who came their way. An old tradition, now virtually obligatory. Plantation owners didn’t stint on food or shelter; they could afford it, and travelers brought outside contact that the isolated planters appreciated.

Derek drove on in silence. Then, “Mr. Seafort, I changed my mind. Let’s camp out for the night.”

“Why?”

“I don’t want to look at plantations.”

I raised an eyebrow, waiting.

“I told you the managers control our estate. They won’t want me around. They’ll patronize me, and push me aside if I ask questions. Let’s not bother to visit.”

“That’s not a good idea.”

“What difference is it to you?”

“Better to face it than brood for the rest of your leave.

Besides, Carr is another day’s ride or more. We’ll stop at a closer estate for the night.”

His tone was petulant. “What’s the point of seeing another family’s holding? It’s mine I care about.”

“You care so much you’d turn tail and run?”

Even in moonlight I could see him flush. “I’m no coward.”

“I didn’t say you were.” But I had. Inwardly, I sighed.

“I’ll handle it, Derek.”

“How?”

“I’ll do the talking, and we won’t tell them your name.”

Ahead was a gate, and a dirt service road that wound into a heavy woods. A wooden sign above read “Branstead Plantation.”

“Slow down. Take that one.”

Reluctantly he turned into the drive. “Mr. Seafort, I feel like a welfarer asking for a handout.”

“That’s the system here. Go on.”

Nothing but woods for a good mile. Then, a clearing where remains of huge brush piles skirted the edge of plowed fields that stretched as far as the eye could see.

Our road straightened, ran alongside the field. After another two miles I began to wonder if the road led to a homestead, but abruptly we came on a complex of buildings set around a wide circular drive. Barns, silos. A heliport. Farmhands’ shacks. They surrounded a huge wood and stone mansion that dominated the settlement.

We got out to stretch. A stocky man in work clothes emerged from the stone house, walked to where we waited.

“Can I help you boys?”

“We’re travelers,” I said.

“The guest house is over there.” He pointed to a clean but simple building that seemed in good repair. “We don’t serve separate for the guests; you’ll eat with us in the manse. We dine at seven.”

“Thank you very much,” I said, but he’d already turned to go.

“Welcome.” He didn’t look back.

We carried our duffels into the guest house. A row of beds sat along one wall, with hooks and shelves on the wall opposite. Around the corner, a bath. The lack of privacy wasn’t unlike a wardroom.

Derek’s tone held wonder. “He didn’t care about us. No questions.”

“Don’t you know about travel in the outland?”

“My father was born here. I wasn’t.”

“Then read the holovid guides, tourist.”

I opened my duffel.

Derek sorted through his clothes. “I’m not a tourist.” His voice was tremulous. “This is my home. Earth never was.”

“I know, Derek.” I’d have to remember not to tease about certain things.

We washed and changed clothes. In Naval blue slacks and a white shirt, I could have been any young civilian. Shortly before seven we strolled up the drive past a field of grain to the main dwelling. From the plank porch we could hear loud conversation and the friendly rattle of dishes.

Derek fidgeted with embarrassment. I knocked.

“Come on in.” A well-fed balding young man in his thirties. “I’m Harmon Branstead.” He stood aside. The entrance room was rough-hewn but comfortable, well furnished with solidly built furniture.

“Nick, um, Rogoff, sir.”

Derek shot me an amazed glance. I gulped, breathing a silent apology to Lord God. Whyever had I chosen the name of the man I’d murdered? I said hastily, “And my friend Derek. We’re sailors.”

“A local ship?”

“Hibernia,sir. The interstellar–”

“We all heard Hiberniadocked. Quite an event.” He held out his hand. “Welcome to Branstead Plantation. How long will you stay?”

“Just the night. We’ll be on our way in the morning.”

“Very well. Come eat with us.”

We were the only guests. Supper was at a long plank table in a dining room that was large but homey. The planter and his wife, their small children, and two farm managers sat at table with us. Hefty platters of home-cooked food were passed around.

Derek asked, “Did you build this place, sir?” He glanced at the stuccoed walls, the comfortable furnishings.

“My grandfather did,” said Branstead. “But I’ve added about ten thousand acres to cultivation, and put up a few more buildings.”

“Very impressive,” I said.

“We’re the fourth largest on Eastern Continent.” His voice was proud. “Hopewell is first, then Carr, then Triform, then us.” Branstead passed creamed corn to his older son, a boy of nine or so. “As soon as we get the machinery paid off, I’ll open some new acreage. Then we’ll see. Maybe by the time I pass it on to Jerence we’ll be the biggest.” He beamed at his son.

“I’d think estates would get smaller over the generations,”

said Derek. “Divided among all your children.”

“Divided? Lord God, no! Primogeniture is the rule. Firstborn.” Branstead nodded at his younger child. “Of course, everyone is well provided for, but the land stays intact. We wouldn’t have it any other way.”

“How large is your plantation?” I asked.

“We’re only three hundred thirty thousand, but we’re growing. Another seventy-five thousand and we’ll pass Triforth. Hopewell is eight hundred thousand acres.” A pause.

“Carr is seven hundred thousand, but they don’t really count as they’re no longer family-run.”

I spooned myself more corn, passed it on. “What’s Carr?”

My tone was careless.

“One of our neighbors. The estate was owned by old Winston, ‘til he died. We all thought they’d stagnate, but I have to admit, Plumwell’s doing all right, even if there’s talk that–” He bit off the rest.

Derek toyed with his food.

Branstead leaned back in his chair. “So, you boys are Navy.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Smart of you not to wear your uniforms, Mr.–Rogoff, is it? I myself wouldn’t hold it against you, but there are some... “

“I’m on leave. Otherwise–” I was proud to wear the uniform, and resented any implication to the contrary. My back stiffened.

“Now, don’t take offense. Some folks see Naval blues and blame the sailors.”

“For what?”

“The usual: you slap export duties on what you send us, and we can’t ship our produce except in Naval hulls. Makes for unfair trade, and we’re paying dearly.”

Derek’s eyes flickered to the comfortable house.

Branstead shrugged, his manner depreciating. “As a nation, I mean. We’re the breadbasket of the colonies. Do you know how much food Hope Nation ships back to Earth? Millions of tons. Once you lift it out of the atmosphere, vacuum cold storage costs nothing. Where are you boys from, anyway?”

“Earth,” I told him. “We’re going on to Detour.”

“When you get home, tell them we want a new tariff bill.”

We drifted to politics and current events, that is, as current as they could be after eighteen months of sail.

After dinner Derek and I settled into the guest house. I sank onto my bed with a sigh of relief. “Why did I blurt out the name Rogoff? I felt his presence all through the meal. I shouldn’t have done that.”

His tone was accusing. “I thought you said you knew how to handle it.”

“You got to see a plantation, didn’t you?”

He grimaced, but without rancor. I got into bed and turned out the light.

Derek tossed and turned for hours, waking me each time I drifted to sleep. In the very early hours he got up quietly, put on his clothes, and slipped outside. Just as dawn was breaking he crept back to his bed, waking me once more.

In the morning, I dressed quickly, anxious for my first cup of coffee. Derek paced. “Look, sir, we can’t go on to Carr.”

I raised an eyebrow. “That again?”

“The manager won’t talk to us.” He sat, stood again immediately. “We’ll learn nothing. And I won’t beg, not on my own land.”

I tried to soothe him. “One thing I’ve learned as Captain, Derek. You’ll have enough problems without worrying about ones that haven’t come up yet. We’ll play it by ear.”

His look was dubious. After a while, he sighed. “All right.

Tell them I’m your cousin or something.”

Thanks to Derek’s nocturnal meanders, we’d slept in until well past nine. We were prepared to leave without breakfast but the housekeeper insisted on feeding us a simple meal that grew into a gargantuan feast.

I was eyeing the last of my coffee when Harmon Branstead looked in. “Where do you go from here, boys?”

“North, toward Carr. Maybe beyond.”

“Stop at Hopewell if you have time. Their automated mill and elevator is astonishing.”

“Thank you.” I glanced at my watch. I could imagine nothing less interesting.

Derek pushed back his chair. “Ready, Mr. Seafort?”

“Yes.” I got to my feet. “Drive the car around. I’ll get our duffels.”

“Thanks for your hospitality, sir.” Derek hurried out. I headed for the stairs.

“Just a moment,” said Branstead then to a farmhand, “Randall, get their bags.” When we were alone, he eyed me with distaste.

“Sir?”

His face was cold. “In Hope Nation, hospitality is a matter of tradition, not law. In that tradition, I opened my home to you. I sat you at dinner with my own children.”

“Yes, sir?”

He shot, “Who are you?”

“Nick. Nick Rog–” My voice faltered.

“Seafort, I believe he called you. I don’t know why you chose to lie, but it’s despicable. You were a guest! Get out, and don’t come back!”

My face flamed. “I’m sor–”

“Out!”

“Yes, sir.” I headed for the door with as much dignity as I could muster. Beyond, in the haze, Father glowered his disapproval.

My hand on the latch, I hesitated. “Mr. Branstead, please... “ I glanced at his face, saw no opening. “I was wrong. Forgive me. My name is Nick Seafort. I–”

“Are you really from Hibernia?’“Yes.”

His skepticism was evident. “You don’t look like the sailors we see hereabouts.”

“We’re officers.”

“Why should I believe that?”

I took out my wallet, handed him my ID.

His glance went to my face and back. “A midshipman.”

“Not anymore. It’s an old card.”

“They wouldn’t have you?”

“They had no choice. I’m, ah, Captain now.”

“You’re the one!” He studied me. “Everyone’s heard, but I don’t think they said the name... Why lie about it, for heaven’s sake?” His tone had eased to one of curiosity.

I had to do something to make amends. “My friend Derek.”

“Yes?”

“Derek Carr.”

“Is he related– Oh!” He sat.

Gratefully, I did the same; my knees were weak. “He’s a midshipman now, and he’ll sail with us. Before we left he wanted to see... “I found it hard to raise my eyes. “Mr.

Branstead, I’m ashamed.”

“Well, there are worse things than deceit.” His voice was gruff. “You’re going on to Carr, then?”

“Yes. He’s very nervous about it. What will the manager–Plumwell, you said–do if he visits?”

His fingers drummed the table. “All our plantations are family owned. There’s never been a case where the owner isn’t in residence. Until now. Will Derek come back to stay?”

“Count on it.”

“Winston wasn’t well, the last few years. He relied heavily on Plumwell. If it weren’t for Andy, they could have lost most everything when credit was so tight. Plumwell may have saved the estate.” A pause. “So if he’s come to think of it as his own... “

I waited.

“He feels strongly about it. They’ve petitioned Governor Williams for a regulation granting rights to resident managers, though that change could take years. If an heir showed up now... “He glanced at me, as if deciding. “Yes, perhaps it’s best to use another name.”

“Is it safe to go?”

“Mr., ah, Seafort... Hope Nation is far from Earth; settlers have handled their own affairs for years. We have a certain spirit of independence that’s hard for you visitors to understand. When a problem gets in the way... we remove it.”“Would he–”

“I don’t know. I won’t mention you if I run into Plumwell.” Branstead stood.

“Thank you. I’m sorry I deceived you. I see now there was no need.”

“You couldn’t know that.” Branstead, somewhat mollified, walked me to the door. “Tell me, has the Navy ever had a Captain your age? How exactly did it come about?”

I owed him that, and whatever else he asked. I forced a strained smile. “Well, it happened this way... “

Early that afternoon, rain turned ruts and chuckholes into small ponds. Secure in our watertight electricar we hummed along past thousands of acres of cultivation. Branstead gave way to Volksteader, then Palabee. Derek asked nervously, “Sir, what will you do?”

“Don’t worry.” I’d decided not to tell Derek about Branstead’s warning, for fear of making him even more nervous.

He would be my cousin. I was practicing how to introduce him when a new mark appeared on the wooden signposts. A few miles beyond, we came to the entrance road, marked with a painted metal sign. “Carr Plantation. Hope Nation’s Best.”

He slowed. “Wouldn’t you rather head back? We’ll have more time for the Ventur–”

“Oh, please.” I pointed to the service road.

It was a long drive, past herds of cattle grazing in lush green pastures, heads bowed away from the rain. Then, endless fields of corn along both sides of the road. Finally a dip revealed an impressive complex of buildings about half a mile ahead.

We came to a stop at a guardhouse with a lowered rail.

The guard leaned into the window. “You fellas looking for something?”

“We’re on a trip up the coast road. Can we stay the night?” He nodded reluctantly. “There’s guest privileges. Every place has them. But why stop here?”

I grinned. “Back in Haulers’ Rest they told us whatever else we missed we had to see Carr Plantation, ‘cause it’s the best and biggest on Hope Nation.”

He snorted but looked mollified. “Not the biggest. Not yet, anyway. Go on in, I’11 ring and tell them you’re coming.”

I waved and we purred off down the road. The rain had stopped, and a shaft of yellow sunlight gleamed through the clouds. Derek hunched grimly in his seat.

“Your middle name’s Anthony?” I asked as a hand sauntered out of the house.

Derek gaped. “Yes, of course. Why–”

The two wings of the huge, pillared plantation house stretched along a manicured gravel drive edged by a low white picket fence. Beds of unfamiliar flowers were interspersed among clean, strong grasses mowed short.

“You the two travelers?” The ranch hand.

I stepped out of the car. “That’s right. Nick Ewing.” I put out a hand. Well, I’d told the truth. At least some of it.

He broke into a grin. “Fenn Willny. We don’t get many come through here anymore, the word’s got out the boss doesn’t like it. He’s soft on joeykids, though. Hasn’t got any of his own.” He gestured to the mansion. “We tore down the guest house last spring. Travelers stay upstairs. You eat in the kitchen. Come on, I’ll take you to the boss.”

We followed him inside. The mansion was built on the grand scale. Polished hardwoods with intricate carving decorated the doorways, bespeaking intensive labor at huge cost.

The furniture in the hallway was elegant, expensive, and tasteful. Fenn Willny led us to a large office on a corridor between a dining room and a sitting room furnished with “Swedish Modern” terrestrial antiques that must have cost a fortune.

The manager’s eyes were cold and appraising. He made no move to welcome us. I glanced at Derek, my stomach churning. What if the manager asked some question I couldn’t answer? Why had I ever agreed Derek was a cousin? “Mr. Plumwell, these are the two travelers, Nick and...”

“My cousin Anthony.” I grabbed Derek’s arm and propelled him forward. “Say hello to Mr. Plumwell, Anthony.”

I jostled his arm.

Derek shot me a furious glance. “Hello, sir,” he mumbled.

I leaned forward confidentially, speaking just loud enough for Derek to hear. “You’ll have to pardon Anthony. He’s a little slow. I look after him.” Derek’s biceps rippled.

The plantation manager nodded in understanding. “Welcome to Carr Plantation. You’ll be leaving in the morning?”

It was a clear suggestion.

“Yes, sir, I guess so.” I looked disappointed. “Actually, I was hoping–well, I know it’s foolish.”

“What’s that, young man?” He looked annoyed.

“We only have two days left of our vacation, Mr. Plumwell. I work, and Anthony’s in a special school.” From Derek, a strangled sound. I said, “We’ve never seen a big plantation before, and I was hoping somebody could show us around. Of course I could pay... “

I couldn’t read Plum well’s expression, so I rushed on.

‘ They said to see either Carr Plantation or Hopewell, because they were both special. But Hopewell’s too far, and I don’t know when we’ll get out together again.” I spoke loudly to Derek. “Anthony, maybe next year if I get a few more days vacation we’ll go to Hopewell. That’s the bigger one.”

Derek’s color rose. He breathed through gritted teeth.

Plumwell frowned. “I suppose you’re city boys and don’t know. It’s an insult to offer money for hospitality on a plantation; that comes with the territory. Anyway, Hopewell is nothing special. We’re the innovative ones.”

He paused, looking us over. “We’re not in the tour business, but I guess I could spare a hand for a few hours, seeing your brother’s retarded. But don’t let it get around back in Centraltown or we’ll be flooded with freeloaders.”

“Zarky!” I nudged Derek. “Did you hear? He’s going to show us a real plantation, Anthony.” Derek’s lips moved, but he turned away and I couldn’t see what he said. “He’s real happy, sir. It’s all he’s talked about since Centraltown.”

I rolled my eyes.

Plumwell winked in understanding. “Why don’t you boys stow your gear in your room. I’ll have Fenn take you around the center complex before dinner.”

“Great, sir!” I shook hands. “Shake hands with Mr. Plumwell.” Derek fixed me with a peculiar stare. I pushed him forward. “Anthony, remember your manners, like we taught you!” Livid, Derek offered his hand to the manager, who gave it a condescending squeeze. “Good boy.” I patted Derek on the back.

Fenn led us up a grand staircase to the second floor, and continued on a smaller staircase to the third. The rooms were clean and adequate, but less ornate than in the lower part of the house. “I’ll wait for you in the front hall.” He loped downstairs two steps at a time.

I closed the door behind us, dumped my duffel on the bunk.

White-faced, Derek glared lasers across the room.

“Something wrong?” I sorted through my belongings.

Without warning he launched himself across the bed, clawing at my neck. I caught his wrists as I fell backward. He dove on top of me, seeking my throat.

“Listen!” It had no effect. He strained to break from my grasp. “Derek!” He thrashed wildly until his wrists broke free. “Stop and listen!” At last, he got his hands on my windpipe.

Unable to breathe, I twisted and heaved, throwing my hips and bouncing him up and down. When he bounced high

enough I thrust my knee upward with all my strength. That stopped him. With a yawp of pain he rolled to the side, clutching his testicles. I rolled on top of him. Sitting on his back I forced his arm up between his shoulder blades, and waited.

He grunted between his teeth, “Get off! I’ll kill you!” I slapped him sharply alongside the ear. He struggled harder.

Each time he heaved I pulled his arm higher behind his back.

Finally he lay still. “Get off!” A string of curses.

“When you’re ready to listen.”

“Off, you shit!”

I slapped him harder. I liked him, but there were limits.

Finally he lay still. “All right. I’ll listen when you get off.”

I let go and sat on my bed. “You have a complaint, Derek?”

He bounded to his feet, sputtering. “Your retarded cousin Anthony? You say that in my own house?’“Do they want company, Derek?”

My calm question gave him pause.”No, not much. Why?”

“What did I get us?” He was silent. “A guided tour,” I answered myself. “A tour of the whole place. Anyway, you said I should call you my cous–”

“I’m a little slow? A, SPECIAL SCHOOL? How DARE you!”

I let my voice sharpen. “Think! You can ask anything you want and they won’t take offense. They won’t even know why you’re asking.” As the realization sunk in he sank slowly onto his bed. “I got you in, when you didn’t have the guts to come. I arranged a guided tour. I heard Vax call you retarded, and you took it. What in God’s own hell is the matter with you?”

“That was the wardroom,” he muttered. “Not my own house.”

“What difference does that make?”

“You’d have to be one of us to understand. In your home you have respect. Dignity.”

I shrugged. “You’re just a middy. You don’t get dignity until you make lieutenant.”

I think at that moment he’d forgotten entirely about the Navy. He looked at the marks on his Captain’s neck and gulped. “I’m sorry, sir.” His voice was small.

“I have a right to dignity too,” I told him. “Look what you’ve done to mine.”

“I shouldn’t have touched you.” His gaze was on the floor.

Well, I’d told him to treat me as senior midshipman rather than Captain. Look where it got me. “You’ll be sorrier.

Seven demerits, when we get back to the ship.” Oddly, it made him feel better. It made me feel better too. My throat hurt. I giggled. “I admit, though, you had provocation.” I snickered, recalling his fury in Plumwell’s office. The more I thought about it, the funnier it seemed.

Watching me roll helplessly on my bed in silent mirth Derek glowered anew, but after a while he couldn’t help himself and began to laugh with me. After a few moments we stopped. I wiped my eyes.