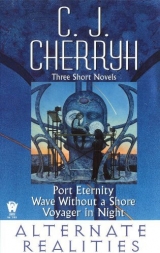

Текст книги "Alternate Realities (Port Eternity; Wave without a Shore; Voyager in Night)"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

That was never changed.

“We’d better get to work,” Griffin said.

So we gathered up our used trays and weary bones; and we carried them back to the galley, Dela and I, while the others set themselves to their business.

There was food to be carried up; and we filled tanks and ran them up; trip after trip in the lift, until my lady was staggering with the loads. And we broke a bottle of the wine, glass all over the corridor, which I hastened to mop up, picking up all the glass. It was like blood spilled there, everywhere, running along the channels of the decking: I thought of that, with our clothes stained with it from the spatter, and the hammering that never stopped. My lady looked distracted at the sight—so, so small a thing threatened her composure, when larger things had not. We were tired, both of us.

“Where’s Vivien?” Dela wondered sharply, with that tone in her voice that boded ill for the subject. “Where’s Vivien all this time?”

“Probably at inventory,” I offered, not really thinking so. “I’ll go find her.”

“I will,” my lady said, with that look in her eye.

Ikept working. That was safest.

And it was not until my next trip topside that I found Viv, who was busy storing items in the freezer. Immaculate Vivien. No hair out of place. At least she was working.

I added my own cart to the lot and began to help. “Did my lady go to rest?” I asked: it was evident Dela had found her—very plain in Viv’s sullen enthusiasm for work. But Dela was nowhere about the dining hall.

“She went to take a bath,” Viv said, all brittle. “You might, you know.”

“I’m sure you haven’t worked up a sweat.”

Viv rounded on me, with such a look in her eyes, on her elegant oval face, that I had never seen. “You,”she said. Just you, as if that were all the fault. Her lips trembled; her eyes brimmed.

“Viv,” I said, contrite, and reached out a hand: I was greatly shaken, not having seen that coming.

She struck my hand down and turned her face away, went on about her work. My lady must have been very hard with Viv. And now and again while we worked she would wipe fiercely at her eyes.

“Viv, I’m sorry.”

“Oh, was it yourdoing?” She looked at me again. It would have made me laugh, because I had never seen Viv’s face like that with the mascara smeared like soot. But I was far from laughter. It was like seeing wreckage. Viv started to cry; and I put my arms about her, just held on to her until she had gotten her breath and shoved me hard.

That was all right. Viv was afraid as well as mad and tired. I knew what that felt like. “It’s all stupid,” she said. “It’s none of it going to work.”

Viv indeed had a mind.

“Griffin says they might be trying a rescue after all,” I offered.

“They’re not,” Vivien judged, and turned her shoulder to me.

I emptied the cart and took it down for another load.

So my lady had had her fling at work and bravely at that, and now she had exhausted herself enough to rest; but I had things yet to do. And Griffin and those with him—they were only now bringing their equipment up the corridor to lift it to middecks, clatter and bang.

It was lonely down there after they had gone; I worked there by myself, loaded up two carts with the last that we had to bring up.

What if it should break through of a sudden, I thought. What if it should be now? I pushed my carts into the lift and rode it up into safer levels, the hammering distant up here and easier to forget.

So we fought, with our wits and our small resources; and the deadliest things we had found in all the ship were the welders that Griffin used to fortify our poor shattered bow.

Viv was not talkative. It was not a good day for her, not in any sense. She sulked about the things we had to do together, and her hands shook when the pounding from belowdecks would get loud. She complained of headache; doubtless that was true. I thought that I might have one if I slowed down and let it have its way.

But Dela came out of her retreat again, bathed and fresh, and helped us, which I think scandalized Viv, and which Viv blamed me for. All the same the working comforted Dela, and she smiled sometimes, braver than we when she had a task under her hands: only sometime the facade cracked and I could see how nervous she was, how her eyes would dart to small sounds. Viv hardly knew how to react to this: I think it was the first time my lady had ever gotten to watch Viv work, which was, excepting Viv’s trained functions, dilatory and involved much motion over little result. And Viv was trying to reform this tendency under that witness, but habit was strong. It would have been funny except that poor Viv was so distracted and so unhinged I remembered the tears.

We knew, when we were finished, how much of everything we had, and we had taken a great deal of it into storage on main level, including bedding enough for us all if we had to sleep here; and we had filled the huge tanks for Vivien’s domain topside. Vats and pipes everywhere up there; but there was a lot of water involved, and we felt the more secure for that. That was another thing that gnawed at Viv, because my lady insisted on Viv telling her what it all did while I was there to hear it—because, my lady said, something might happen to one of us. Poor Viv. That was not the thing she wanted to think about.

But came the time that all of us had run out of strength, and Griffin’s party came up to the dining hall, all dirty as they were, to the dinner we fixed on the last of our strength—even Viv’s. And Lynn looked ready to fall over on the table, sitting there stirring her soup about without the strength to get it to her mouth, and Modred was as down as I had ever seen him, not mentioning the others, who had burns and cuts from the metal and who looked as if a dinner at table was only further torment. They would probably rather a sandwich in solitude, and maybe not that. Griffin was drawn as the rest of them ... as worn, as miserable; but he smiled for Dela, and made a joke about frustrating our attackers.

Then there was a signal from the bridge, which meant that something had happened, and we staggered away from our supper, all of us.

It knew, I thought, it knewthat we were trying to rest: our hammering had stopped, and maybe it picked up that silence inside. So we stood shivering on the bridge, under the images of the dead ships and the bleeding space outside, and listened to that nonsensical sound that rumbled and roared like a force of nature, Even Dela was there to hear, and Viv—Viv just blanked, frozen in the center of the room.

“Respond?” Modred asked.

“No,” Griffin said.

“I might point out—”

“No,” Griffin said. “No more reaction to it. They know too much about us already, I’m afraid.”

Modred cast a look toward my lady, not real defiance; but there was that manner to it. “I might point out we have defenses. But they’re worth nothing in the long term. We should talk while we have something to talk with. I have a program—”

“No,” Dela said, ending that. Modred only looked tired, and turned back to the board.

“Leave it,” Griffin said. “All of you—go below and sleep. All of us can use it. Hear?”

We heard. Modred shut down; Gawain left his place, and Lynn and Percy did. Myself, I wanted nothing more than to go down to my own bed and rest. I saw my lady go off arm in arm with Griffin; and remembered the dishes with an ache in my bones and a wish to leave them and go curl up somewhere.

No Viv. Percy had gotten her by the arm and they were on their way out the door. Only Lance stayed, looking like death and all but undone.

“Can’t come,” I said. “I’ve got the dishes.”

“I’ll help,” he said. We worked like that, Lance and I, both of us staff and responsible for our born-man and for the things not in anyone else’s province. So he came with me. I don’t know which of us was more tired, but I reckoned it was Lance: his poor hands were burned and the china rattled in them—I reckoned that water would hurt on the burns so I did all the washing.

And after that, we went to see to our born-men, who were together: nothing to do there. Dela and Griffin were locked in each other’s arms and fast asleep. I looked back at Lance who had come closer to the door, made a sign for quiet—but he only stood there, and a great sadness was on his face.

I dimmed the lights they had forgotten or not cared about. “Come on,” I whispered, and took him by the arm, walked with him outside and closed the door.

“Go on down,” he said. “I’ll stay hereabouts.”

“Lance, you shouldn’t. You’re not supposed to.”

“He’s good to me—you know that? He knows, like you said. And he loves her. And all of today—he never had any spite. Nothing of the kind. And he might have. Anyone else would have. But he treats me no different for it.”

“He’s all right,” I said finally. “Better than any of the others.”

“Not like any of the others,” Lance said. He shook his head, walked away with his head bowed—the way Griffin had walked away that night, as sad. Not like the others. Not someone Dela would tire of. Not someone to put aside. And kind. Maybe he wished for Robert back. But Lance was in the trap. He had so little selfishness himself—he opened to generosity. He was made that way.

“Lance.” I caught up with him, took his arm. “Lance—I don’t want to be alone.” I said it, because he had too much pride. He let me take his hand. “Come downstairs,” I asked him.

He yielded, never saying anything, but he walked with me to the lift, and I was all but shaking with relief, for pulling him out of that. We should have a little comfort, we two, a night lying close, among our friends.

We came in ever so quietly, Lance and I, into the mostly dark sleeping quarters ... stood there a moment for our eyes to adjust, not making any noise. Everyone was on the couches, and a tape was running; the screen flickered. I was sorry that we had missed the start, because it was maybe the best thing to do with the night, to be sure of quiet dreams. We could still hear the hammering.

We might slip in on the dream, I thought: when my eyes had adjusted enough that I reckoned not to bump into anything, I crossed the room and looked up at the screen to know what sort it was.

And then my heart froze in me, and I flew back across the room to my locker, and Lance’s. I felt there, on the shelf, but the tape was gone; was in the machine; running, and they were locked into it– allof them.

Maybe my face showed my terror. Lance had seen; he looked only half disturbed until he looked at me, and reached out his hand for mine. “Viv,” I said, reckoning who would have stolen. “O Lance, we’re ruined, we’re lost, they shouldn’t—”

“We can’t stop it,” he said, half a whisper. “We daren’t stop it halfway—not that one. They’d never sort it out.”

“It’s my fault,” I mourned. “Mine.” But he put his arms about me and held, which was comfort so thorough I had no good sense left and held to him, which was all I wanted.

“We might use it too,” he said. “If it’s beyond stopping. I want it, Elaine.”

So did I, for twisted, desperate reasons—even if I lost him again. So we joined them, helpless in the dream that had gotten loose on the ship, that filled the Maidand told us what we might have been.

But for some of us it was cruel.

XI

Then that same day there past into the hall

A damsel of high lineage, and a brow

May-blossom, and a cheek of apple-blossom,

Hawk-eyes; and lightly was her slender nose

Tip-tilted like the petal of a flower;

She into hall past with her page and cried,

“... Why sit ye there?

Rest I would not, Sir King, an I were king,

Till ev’n the lonest hold were all as free

From cursed bloodshed, as thine altar-cloth

From that best blood it is a sin to spill.

My name? ...

Lynette my name.”

It was a good way to have passed that aching night—if it had been any other tape. We were free for a time; we knew nothing about the terrible place where we were.

I loved and lost again. But I knew the terms. And there was Lance with me, who had learned the tape under his own terms, and who had made his peace with what he was. He was trapped, the same as I was. And not afraid anymore. His world made sense to him, like mine to me.

But when we woke, with the hammering still going on the same as before—when we stirred about with the light slowly brightening to tell us it was another morning in this place—it was hard to look at one another. Everyone—crew and staff—moved about dressing, and no one looked anyone else in the eye.

That was what it did to us.

I went over and took the tape myself, and no one said anything; I stored it in my locker again. But they all knew where, and I reckoned so long as we lasted in this place, they would not let it alone. Could not let it alone. Lance came and laid his hand on mine on the locker door, and pressed my fingers. He was afraid too, I thought. Of the others. Of what now we knew we were.

Only there was Percy, who came to us, his face all distressed. Who just came, and stopped and stared. Gentle Percivale.

“It’s a tape,” I said out loud, so they all could hear. “It’s an old story, an amusement. Lady Dela owns it and let me borrow it. You have to understand.”

But there was no easy understanding. Not for that.

“Viv said—” Percivale began, and dropped it.

Vivien.I looked her way; and Vivien met my eyes by accident. She was just putting her jacket on; and her head came up. It was not a good look, that. She turned away and began sweeping her hair back, to put it up again in its usual immaculate order.

“We had better get to the bridge,” Gawain said then quietly, “and see how the night went.” He started to the door, looked back. Percivale had joined him. And Lynn. “Modred?”

Everyone looked. Modred had been sitting on the couch getting his boots on—and still sat there, inward as ever. And when Gawain called him he got up and went for the door, as silent, as quiet as ever.

But we got up afraid of him, as we had never been. And it was wrong. I felt it wrong. I intercepted him on his way, took his arm.

“It’s amusement,” I said. But Modred had always been innocent of understandings—without sex, without nerves. “It’s a thing that happened a long time ago, if it ever happened.”

His dark eyes fixed on mine, and I saw something in the depth of them ... I couldn’t tell what. It might have been pain; or just analysis—something that for a moment quickened him. But he had nothing to say. OurModred could make jokes, the lift of a shoulder, the rhythm of his moves; but this morning he was—quiet. Without this language. He used the quieter story tapes; mostly I suspect they bored him, and the more violent ones were outside his understanding. But when one is tired, when one’s defenses are down to begin with—

“Yes,” Modred said, agreeing with me, the way we agree with born-men, to make peace and smooth things over. And he went away with the others.

“Vivien,” I said, turning around. “Vivien, you’ve done this.”

She went on pinning up her hair.

“Let be,” Lance said, taking me by the shoulders.

She was dangerous, I thought to myself, and she ran all our lifesupport up there; and our future food supply; all the technical things in the loft.

But maybe—I tried to persuade myself—that was what we were all doing this morning: maybe we had all learned to look at each other askew; and, we were cursed to know how others saw us.

“Modred,” I mourned. “O Modred.”

“It should never have happened,” Lance said. “It was my fault, not yours.”

“How do we prepare against a thief?” I asked, meaning Viv. But Viv had finished her dressing and swept past us without a look.

“My fault,” Lance repeated doggedly.

“They’ll sort it out,” I insisted, turning round to look at him. “You did. I have.”

“I’m not so sure,” he said, “of either of us.”

“You know better than that.”

“I don’t.” He put his hands in his pockets. “Aren’t we—whatever tapes they put in?”

I had no answer for that. It was too much like what I feared.

“Elaine,” he said sadly. Touched my face as he would have touched Dela’s. “Elaine.”

And he walked away too.

My fault, I echoed in myself. When they all had gone away, I knew who was to blame, who had been selfish enough to bring that tape where it never should have been.

“What’s wrong?” Dela asked at the breakfast table, and sent my heart plunging. We sat, all of us silent: had sat that way. “Is something wrong no one’s saying?”

“We’re tired,” Griffin said, and patted her hand atop the table. “All of us.” He laughed desperately. “What else couldbe wrong?”

It got a laugh from Dela. And a silence then, because some of us had humor enough to have laughed with her if we had had the heart.

O my lady, I wanted to say, flinging the truth out, we’ve heard what we never should; I stole what I never ought; we know what we are ...and that was the terror of it, that we were and were not, locked together in this place apart from what was real.

“Elaine?” she asked, and touched my face, lifted my chin so that I had to look her in the eyes. “Elaine, don’t be frightened.”

“No,” I said. It did her good perhaps, to comfort us. The lion banner looked down on us where we sat at breakfast at the long table among all the deadly things we had gathered. I heard the trumpets blowing when my lady looked at us like that. But louder was the hammering that had never ceased.

Dela smiled at me, a grin broad as she wore for new lovers. But there was only Griffin. It was the banner; it was her fancy moving about her. She smiled at me because I understood her fancy, if Griffin did not—She had her courage back. She had found her footing in this strange place, and there was a look in her eyes that challenge set there.

“I wish there were more to do,” I said.

“There ismore,” Lynette said, suddenly from down the table. “Let us go outside. Let us breach themand see what they are before they come at us. We’ve got the exterior lock—”

“No,” Dela said.

“I’ve been up in the observation deck,” she said. “I’ve seen—if you look very hard through the stuff you can see—”

“Stay out of there,” Griffin said. “It’s not healthy.”

“Neither,” Modred muttered, “is sitting here.”

It was insubordinate. I think my heart stopped. There was dead silence.

“What’s your idea?” Griffin asked.

“Lynn’s got one idea,” Modred said. “I have another. First. If you’d listen to me, sir—my lady Dela. We take the assumption that it’s not hostile. We feed it information. It’s going to stop to analyze what we give it.”

“We feed it information and then what?”

“We try the constants. We establish a dialogue.”

“And in the end we give away the last secrets we have from it. What we breathe, who we are, whether we have things of value to it—I don’t see that at this point. I don’t see it at all.”

Modred remained very quiet. “Yes, sir,” he agreed at last, with that tiniest edge of irony that Modred could put in his flattest voice.

“Modred,” Dela said, tight and sharp.

His face never varied. “My lady,” he said precisely. And then: “I was working on something I’d like to finish. By your leave.

My heart was racing. I would never have dared. But Modred hadno nerves. I hoped he had not. He simply got up from his chair. “Gawain,” he said, summoning his partner.

“I need Gawain,” Griffin said in a level tone, and Gawain stayed. There was apprehension in Gawain’s face ... on all our faces, I think, but Modred’s, who simply walked out.

“He’s very good,” Dela said.

Oh, he was. That was so. That’s why they made him that way, nerveless.

“I’d like,” Griffin said, “monitoring set up below. Shouldn’t be too hard.”

“No, sir,” Percy said quietly. “Not hard at all.”

We dispersed from the table; we cleaned the dishes; we found things that wanted doing, my lady and I; and Vivien. There was the cleaning up of other kinds; there was Vivien’s station—

Oh, mostly, mostly after yesterday, after working so hard we ached ... it was waiting now; and we had so little to do that we found things.

We were scared if we stopped working. And Vivien was in one of her silences, and my lady was being brave; and Lance went down to the gym with Griffin as if there had been nothing uncommon in this dreadful day, the both of them to batter themselves beyond thinking about our Beast.

Might Lynn, I wondered, envying that exhaustion—care for a wrestling round? But no. I had not the nerve to ask. It was not Lynn’s style; or mine; and the crew really did find things to do.

Lynn went out in the bubble ... sat there, hour upon hour, as close to the chaos-stuff as we could get inside the ship. She did things with the lenses there. I took her her lunch up there, trying to keep my back to the view.

“You can see,” Lynette advised me softly, “you can see if you want to see.”

I knew what she meant. I wasn’t about to look.

“I could make it across,” she said. Her thin freckled face and close-clipped skull looked strange in the green light from the screens; but out there was red, red, and red. “I could see.”

“I know you could,” I whispered, hoping only to get out of here without looking at the sights Lynn chose for company. “I’m sure you could. But I know the lady doesn’t want to lose you.”

“What am I?” Lynn asked. “One of the pilots. And what good is that—here?”

“I think a great deal of good.” I rolled up my eyes, staring at the overhead a moment, because something was snaking along out there and I didn’t want to see. “O Lynn, what is that out there?”

“A trick of the eyes. A shifting.”

“Lynn,” I said, because I felt very queasy indeed. “Lynette?”

“Elaine?”Of a sudden something was wrong. Lynn rose half out of her chair, pushed me aside; and then—

Take-hold, take-hold, the alarm was sounding: and Modred’s voice: “ Brace, we’re going—”

I yelled for very terror. “Let me out of here,” I remembered screaming, and flinging myself for the hole that led to the bridge. But: “No!”Lynn yelled, and grabbed me in her arms, hugged me to her and I hugged her and the chair and anything else solid my fingers could reach, because we were losing ourselves—

–back again, a blackness; a crawling redness. I held to something that writhed and mewed like the winter winds round Dali peaks, and hissed like breathing, and grew and shrank—

“—another jump,” I heard a distant voice like brazen bells.

“Modred?” another called.

“Griffin?” That was my lady, like crystal breaking.

My eyes might be open. I was not sure. Such terrible things could live in one’s skull, eyeless and unaided in this place. “We’ve jumped again,” the thing holding me said, the voice like wind.

“Are we free?” I cried. “Are we free?” That was the greatest hope that came to me. But then I got my eyes cleared again and I saw the familiar red chaos crawling with black spiders of spots. And the veins, all purple and green, and the thing to which we were fixed. That was unchanged.

“We’re not free.” It was Percivale’s voice, thin and clear. “It jumped again; but we’re not free.”

There was a moment of silence all over the ship, while we understood the terms of our captivity. Like all the ships before us.

“O God,” Dela’s voice moaned. “O dear God.”

“We’re all right.” Griffin’s voice, on the edge of fright. “We’re all right; we’re still intact.”

“Situation stable,” Modred’s cold clear tones rang through the ship. “Nothing changed.”

Nothing changed.O Modred. Nothing changed. I clutched the cushion/Lynn’s arm so tight my fingers were paralyzed.

“You might have been out there,” I said. It was what we had been talking of, a moment/a year ago. “You could have been outside in that.”

Lynn said nothing. I felt a tremor, realized the grip she had on me. “We’re stable,” Lynn echoed. “It must happen many times.”

“The hammering’s stopped,” I whispered. It was so. The silence was awesome. I could hear my heart beating, hear the movement of the blood in my veins. We were so fragile here.

“That’s so,” Lynn said. She let me go and pushed me back, leaned forward to reach the console. “Modred, I get nothing different on visual.”

I managed to get my feet under me while those two exchanged observations. I stared at familiar things and they were normal. And almost I wished for that horrid dislocation back again, that chaos ordinary minds would feel. We were no longer ordinary. We had learned how to live here. For a moment we had been outof this place, and that was the horror we felt; that drop into normal space again. And comfort was breaking surface again in Hell.

“We’re traveling,”I said. Lynn looked at me, bewildered a moment. “We’re traveling,” I said again. “This place moves, goes on moving; we must have reached a star and left again.”

“Yes,” Lynn said with one of her abstracted frowns. “That’s very probable.—Do you copy that, Modred? I think it’s likely.”

“Yes,” Modred agreed. “Considerable speed and age. I think that’s very much what we’re dealing with. We’re a sizable instability. And we grow. I wonder what we might have acquired this time.”

“Don’t.”Dela’s voice shivered through the com.

“We’re old hands,” came Griffin’s. A feeble laugh. “We know the rules. Don’t we?”

“O dear God,” Dela murmured.

Silence then, a long space.

And about us in the bubble, the chaos-stuff swirled and crawled and blotched the same as before.

“Is everyone all right?” Percivale asked then. “Do we hear everyone?”

I heard other voices, my comrades. Lance was there with Griffin; and Gawain. “Elaine’s with me,” Lynn said. “Vivien?”

Silence.

“She’s blanked,” I said. “I’m going.”

“Vivien,” I heard over com, again and again. I felt my way, hand-over-handed my way from the bubble to the ladder and to the bridge ... across it, through the U where Modred and Percivale were at work. “I’m after Vivien,” I said.

“Gawain’s on the same track,” Percivale said, half rising. “She was at her station when it hit—”

I ran, staggered, breaking rules ... but Viv was weakest of us, the most frightened. I had to wait on the lift because Gawain had gotten there first; I rode it up to the uppermost corridors, floors/ceilings with dual orientation, dual switches, that crazy place where the Maid’s geometries were most alien, where Vivien worked in her solitary makeshift lab. I made the inner doors, and there was Lancelot and there was Gawain before me. They knelt over Viv, who lay on the floor in a tuck, her eyes open, her hair immaculate, her suit impeccable; her hands were clenched before her mouth and her eyes just stared as if they saw something indescribable.

They were afraid to touch her. I was. It was not like blanking, this. It was like the wombs. It was—not; because what Viv saw, she went on seeing, endlessly, like a tape frozen-framed.

“Viv,” Lance said, looked at me as if I should have some hope neither of them did. I sank down. I touched her, and all her muscles were hard.

“It’s your fault,” Gawain said, a strained voice. “It’s your fault. That tape of yours—that tape—”

It was Lance he meant. Gawain’s face was the color of Viv’s. His eyes flickered, jerked, searched for something as if he could not get enough air.

“It was my tape,” I said. “Mine. And Viv that stole it. Wasn’t it? But it’s nonsense. It’s not important. It’s—”

“Viv is lost,” Gawain said.

“Lance. Lance, pick her up. I’ll find a blanket.”

He took Viv’s wrist, but there was no relaxing her arms. He lifted her by that limb, got his arms under her, his other arm beneath her knees, and gathered her to him. I scrambled up. “Just get her out of here,” Gawain said. “Let’s just get her out.”

“How is she?”That was Percivale, on com. “Is she all right?”

“She’s blanked out,” I said, looking up at the pickup, above all the eerie tubes and lines and vats and tanks and glare of lights. “We’ve got her. We’re coming down.”

And then the hammering started again.

Not where it had been. But close.

Up here. Above.

“Oh no,” I said, above the chaos of com throughout the ship. “Oh no.”

It was more than here. It was at our side. It was at our bow. We were attacked at all points of the ship.

“Something might have come loose,” Lance murmured, standing, holding Viv’s rigid body in his arms.

“No,” Gawain said, calmly enough. “No. I don’t think so. Get her to quarters, Lance. Let’s get out of here and seal the door.”